Many Indian kidnap victims found they liked their new lives

THE THREE CHILDREN were playing in a wheat field, several hundred yards from their home outside Loyal Valley, Texas, when the Apaches attacked. One grabbed Willie Lehmann, age 8, and carried him off. Willie’s brother and sister screamed and sprinted for the family’s log cabin. Caroline Lehmann, 9, got away. An Apache caught Herman, 11, and threw him to the ground. Herman fought back, punching, kicking, and biting, but the man overpowered him, ripped off the boy’s clothes, tied him to a horse, and galloped off.

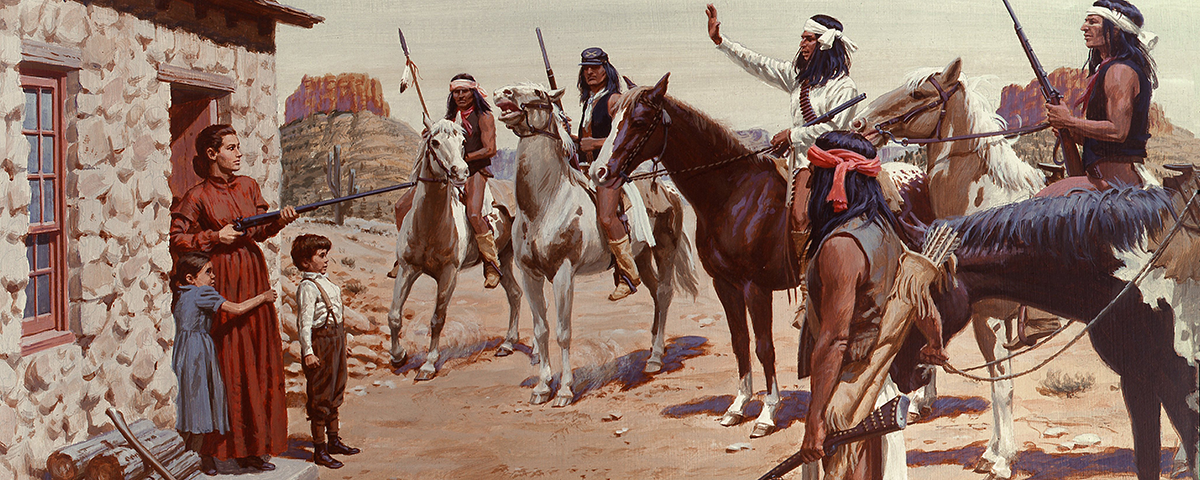

Hearing screams, Phillip Buchmeier, the children’s stepfather, grabbed his gun and ran toward the noise. He was too late. Apaches had taken Willie and Herman. Buchmeier rushed to recruit a posse, but all the neighboring men were off rounding up cattle. It was May 16, 1870, in Mason County, Texas. Buchmeier and his wife Auguste, who had brought her three children to the marriage, were German immigrants scraping a living out of the soil of the Hill Country, where life’s hazards included raids by Indians bent on stealing horses and sometimes children.

Captives in hand, the Apaches rode northwest, raiding another farm and stealing eight horses before vanishing into the dark. Herman was tied across his captor’s mount like a deer carcass, his bare skin burned by the sun and scratched bloody by thorns. Late that night, Carnoviste, the Apache who’d snatched Herman, spotted a calf. He slit the animal’s throat and sliced open its stomach to slurp the milk within—a Plains Indian delicacy. Carnoviste offered Herman a drink. The boy recoiled. Angry, Carnoviste shoved Herman’s head into the calf’s stomach and rubbed sour milk on his face. Herman vomited. Carnoviste fed him raw calf’s liver, another indigenous delicacy. Again the boy vomited. Carnoviste carried Herman to a waterhole, washed his face, and again tied him to the horse. They rode on.

On the band’s fourth frenzied day, the Apaches exchanged shots with ten soldiers from the U.S. Ninth Cavalry. The soldiers killed one Apache and captured several stolen horses. After the skirmish, the Apaches again galloped. Willie fell from the horse on which he was being transported. No one came for him. Alone in a strange land, the boy wandered for three days. The driver of a freight wagon brought him home. His mother asked where Herman was.

“Herman has gone on, Mama,” Willie told Auguste Buchmeier. “They took him on.”

Ten days’ hard riding brought the raiders to their village

in New Mexico. A noisy crowd of curious Apaches surrounded the blue-eyed, sandy-haired, freckle-faced white boy, hollering words

Herman couldn’t understand. An old woman pulled him off the horse, smacked him, and knocked him to the ground. A man with a knife sliced off a tuft of Herman’s hair. Another man pierced the child’s ears with a hot iron, then used the iron to sear scars into the captive’s arm. Herman passed out. When he awoke, Apaches were washing his battered body. One of the men led the boy to a blanket covered with food and Herman ate.

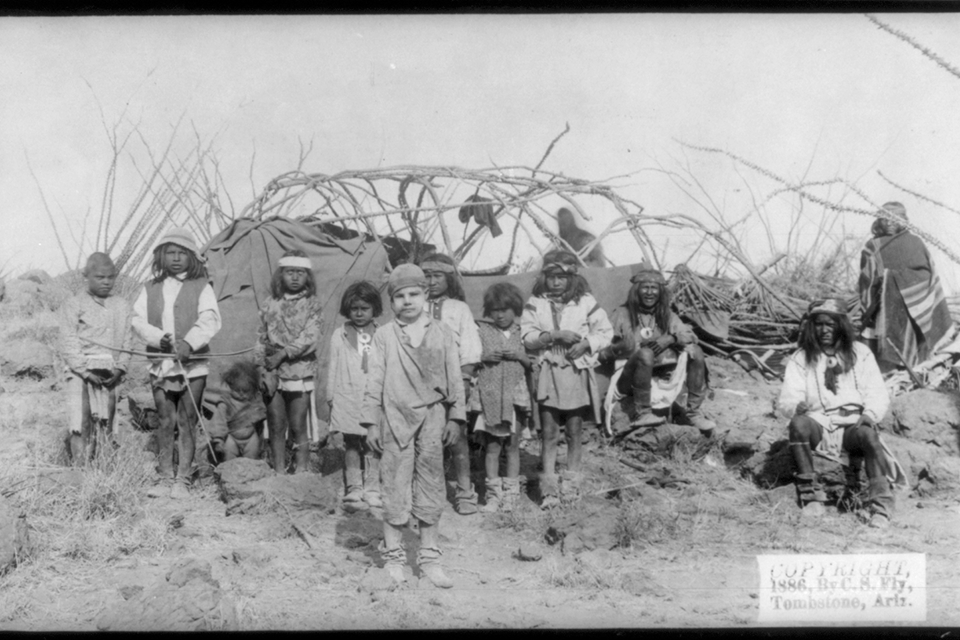

Carnoviste brought Herman to his tent. His wife, Laughing Eyes, welcomed the boy and treated him kindly. The couple named him Enda, or White Boy. Herman was now part of their family. This was not unusual: Southern Plains Indians often adopted children they abducted. Since the Europeans had come, the native population had shrunk, ravaged by smallpox, cholera, and battles with whites. “Child captives,” wrote historian Glenn Frankel, “were one way to replenish the population and bring comfort to bereaved families.”

Laughing Eyes and Carnoviste put Herman to work—at first, mundane chores like fetching water, starting fires, and skinning game, along

with humiliating rituals like washing Carnoviste’s feet and picking lice from the Indian’s hair. As Herman learned Apache, however, Carnoviste began training him in the warrior’s arts—how to fashion arrows and bows and a buffalo-hide shield. And Herman began playing with the village boys—swimming, running races, riding horses.

On July 18, 1870, two months after kidnapping Herman Lehmann, Carnoviste led another run into Mason County. Again, the Apaches attacked the Buchmeier farm. Herman’s stepfather was off working, but Auguste fought back, blasting the raiders with a shotgun, wounding Carnoviste and another Apache. The raiders didn’t harm the family but before departing the Indians grabbed a toy pistol.

Back in New Mexico, Carnoviste, angry that his captive’s mother had shot him, beat Herman. Carnoviste showed the boy the toy gun, which Herman recognized, and lied, telling his prisoner that the Indians had killed his entire family. As far as Herman Lehmann was concerned, all he had in this world was Carnoviste and the Apache.

The Apaches, who lived by hunting and raiding, highly prized those skills. They attacked farms in Mexico and Texas, stealing horses and guns and frequently killing the people they encountered. Deer, antelope, and buffalo provided nearly all their food and clothing. Adolescent Apache boys were eager to prove their prowess in the wild and on raids. Herman Lehmann, aka Enda, was no exception.

His first raid came about a year after his capture, when Carnoviste led a band into Texas. The Indians spotted a tent with a black horse tied nearby. Carnoviste told Enda to steal the horse. When he hesitated, Carnoviste pointed a pistol at him. That settled the issue. Carnoviste handed the boy the pistol and Herman crept toward the tent. As he was cutting the horse’s tether, a white man burst from the tent and fired a shotgun. The buckshot missed Herman but the blast knocked him to the ground. The horse and its owner ran. So did Herman, who hid in high grass until the Apaches summoned him and found that, in addition to failing his first test as a raider, he had lost Carnoviste’s pistol. The next day, the raiders surprised a few cowboys, took their horses, and celebrated by roasting a stolen cow. Pushing deeper into Texas, the band snatched horses and exchanged gunfire with angry whites before driving their purloined horses home.

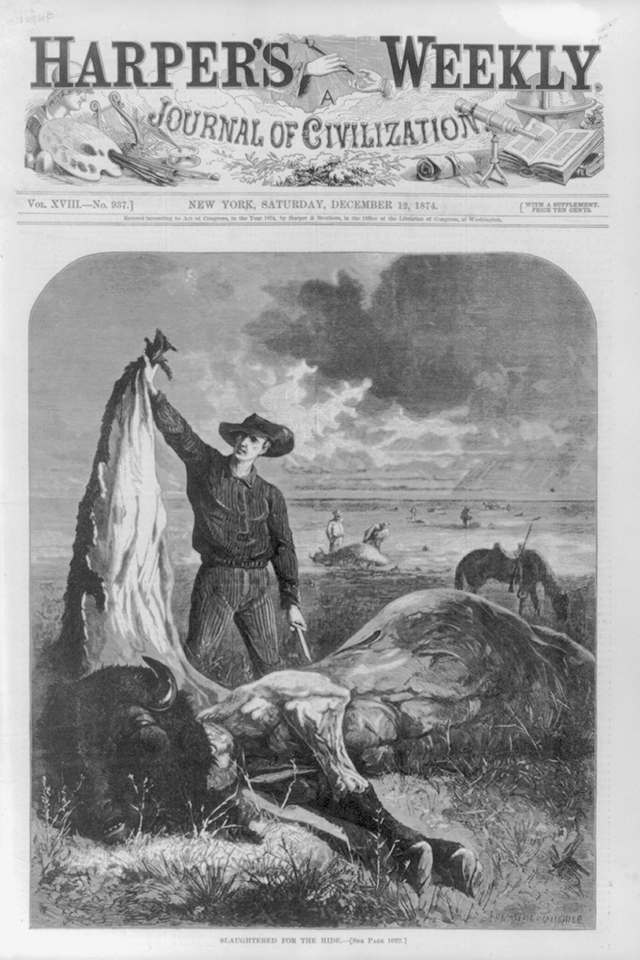

On another raid, a dozen Apaches, including Carnoviste and Herman, surprised four buffalo hunters, a hated subset of the white race. To feed the market for leather, riflemen like these were shooting thousands of buffalo, shipping their hides East and leaving the carcasses to rot, systematically destroying the basis of the Indians’ culture. The Apaches captured one of the four, a Mexican; the rest fled. Carnoviste left Herman to guard the Mexican and led the other Apaches after the fleeing hunters. The Mexican threw a rock at Herman; Herman loosed an arrow that barely grazed the Mexican, who raised his hands in surrender. When Carnoviste returned, Herman explained what happened. Carnoviste ordered him to kill the Mexican. Herman put an arrow in the man’s heart. Now scalp him, Carnoviste ordered. Herman hesitated, then obeyed. “I took my knife, made an incision all around the top of his head, grasped his hair with my fingers and gave a quick jerk backwards,” he later recalled. “The scalp came off with a report like a pop-gun.”

On a raid deep into Mason County, Texas, Herman helped steal horses and mules from his former neighbors. Passing the Lehmann cabin,

the Apaches teased the boy, calling him a paleface and joking that he should go home. He refused, insisting that he was now an Apache. “I did not want to go, for I had learned to hate my own people,” he later recalled.

In the spring of 1876, six years after his capture, Herman, 17, fled the Apaches. He would have stayed with the band longer but for a drunken brawl. Soused on cheap whiskey, a group of Apache men began fighting. A medicine man killed Carnoviste in front of Herman, who attacked the man who had slain his foster father, killing the shaman with an arrow to the heart. Certain that the medicine man’s relatives would be coming for him, Herman fled on horseback and took shelter in a remote canyon. “I was utterly alone in the wide world without a friend or protector, a hunted and hated thing to be slain on sight,” he later recalled. “I was isolated from the Indians and afraid of the whites—absolutely alone.”

Herman lived all summer in the canyon, surviving on what he caught and killed. Scared and lonely, that autumn he left his hideout, “a sense of dread weighing on my mind.” Among the region’s tribes were Comanche, a tribe that sometimes fought the Apache. Encountering a Comanche band, Herman sneaked so close to the Indians’ campfire he could hear the men talking and laughing. Desperate for companionship, half-expecting to be killed, he walked toward the men, who leaped to their feet and grabbed weapons. But no violence broke out. A Comanche who spoke Apache translated as Herman told his long, strange tale of life among the whites and the Apache, then asked to become a Comanche. “I was told I would be taken into the tribe on condition that I would always remain a Comanche, that I would help them fight their enemies, and never surrender to the white men,” he said later. From the Comanche, Herman Lehmann, aka Enda, got a new name—Montechena—and for the rest of his life he considered himself a Comanche, a tribe he preferred to the Apaches. “As a rule, the Comanche are a fun-loving people and enjoy a good laugh,” he recalled later. “The Apaches are morose.”

“Fun-loving” was not a phrase that most Texans of the 1870s would have used to describe the Comanche. In the 40 years since Americans had begun moving into Comanche territory in Texas, the groups had fought a merciless war characterized by gruesome atrocities inflicted against one another. “Neither side believed the other was fully human,” Glenn Frankel wrote. “Comanche saw the Texans as invaders without conscience who occupied their lands, destroyed their hunting grounds and broke every promise. Texans saw Comanche as human vermin, brutal, merciless and sadistic.”

By 1876, when Herman joined the Comanche, the tribe was losing that war. The year before, the U.S. Army had driven most Comanche onto a reservation in Oklahoma. Herman was now part of a band of about 50 diehards determined to fight the interlopers. Through spring and summer 1877, Herman and his Comanche band rampaged through northwest Texas, killing buffalo hunters and leaving mutilated corpses as a warning to others. “Scarcely a day passed without a skirmish or a fight,” Herman recalled. But the Comanche were outnumbered, surrounded by whites and chased by Texas Rangers and the U.S. Cavalry. “It looked like our warriors would all soon be killed,” he wrote.

That summer, Army officials convinced Comanche chief Quanah Parker to leave the Oklahoma reservation and travel into Texas in an effort to persuade the renegades to surrender. Parker—son of Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman who was captured by Comanche as a girl, then lived with the tribe for 24 years—had the trust of both whites and Comanches. He located Herman Lehmann’s band and spent four days with them, arguing that if the raiders kept fighting they soon would be killed.

“Finally,” Herman recalled, “our band agreed to go in.”

The renegades followed Quanah Parker into Oklahoma. On August 20, 1877, 58 Comanche, including Herman Lehmann, were approaching Fort Sill when Herman, seeing soldiers coming his way, panicked. He galloped into the nearly Wichita mountains, determined never to be captured.

Herman spent months in the mountains. Early in 1878, Quanah Parker informed him that his mother was still alive. Auguste Buchmeier, who never had stopped searching for her stolen son, wanted her boy home. Herman refused, insisting he was an Indian. It took months, but finally Quanah persuaded Herman to meet his white family.

Escorted by five soldiers, Herman arrived in May 1878 at the small hotel his mother owned in Loyal Valley. Not quite 19, he’d been gone eight years. A crowd of 300, chattering in languages the youth couldn’t understand—German and English—watched as a tearful Auguste hugged her son, who didn’t recognize her. To the young man, his mother was “no more than a white squaw.”

His sister and brother addressed him as Herman, which did sound familiar. Willie and Caroline led their sibling inside for a feast. The dishes included pork, which disgusted Montechena, who knocked the platter of pig meat off the table. That night, Herman refused to sleep indoors in a feather bed, instead sleeping outside on the ground. Willie joined him. In the morning, as his military escort was leaving, Herman tried to ride along and became irate when the soldiers rebuffed him. Several times he ran away. Each time that happened Willie brought his older brother back. “The women would cry around me,” Hermann said. “I did not like tears.”

Herman gradually grew to love his birth family again but, like many former captives, he never fully rejoined white society. He hated school and refused to go, never learning to read. He worked fitfully as a farmhand and a cowboy. For a while, he ran a saloon but he drank too much beer and got into fights. Finally he sold the place. In 1896, he married a white woman and with her moved to an Indian reservation in Oklahoma. He and his wife raised five children on the reservation. In 1927, he moved to Willie’s ranch in Texas, where, at age 72, Herman Lehmann died in 1932.

In 1924, Herman told his story to a white journalist, who ghostwrote Nine Years Among the Indians. The memoir’s title was an

Collections)

—it was eight years—but the book sold well and remains in print. The text recounts, in gruesome detail, stories of Herman’s many battles, but offers little insight into Herman’s feelings about those violent days or why he bonded with people who had brutally abducted him.

Herman did love recounting his adventures—and cashing in on his fame. At county fairs, he’d dress in buckskin and feathers and deliver a performance unique in showbiz history. Atop a horse he’d gallop into the arena, bow in hand and quiver of arrows on his back. He’d chase a calf, shooting arrows at his target’s hooves, making the animal run faster and faster. With a war whoop and a well-placed arrow, he’d kill the calf, leap from his mount, slice open the calf’s torso, and cut out the liver. In the spotlight, with the crowd gasping and cheering, Herman Lehmann would stand and eat the bloody liver raw, Indian style.

_____

An Acquired Taste

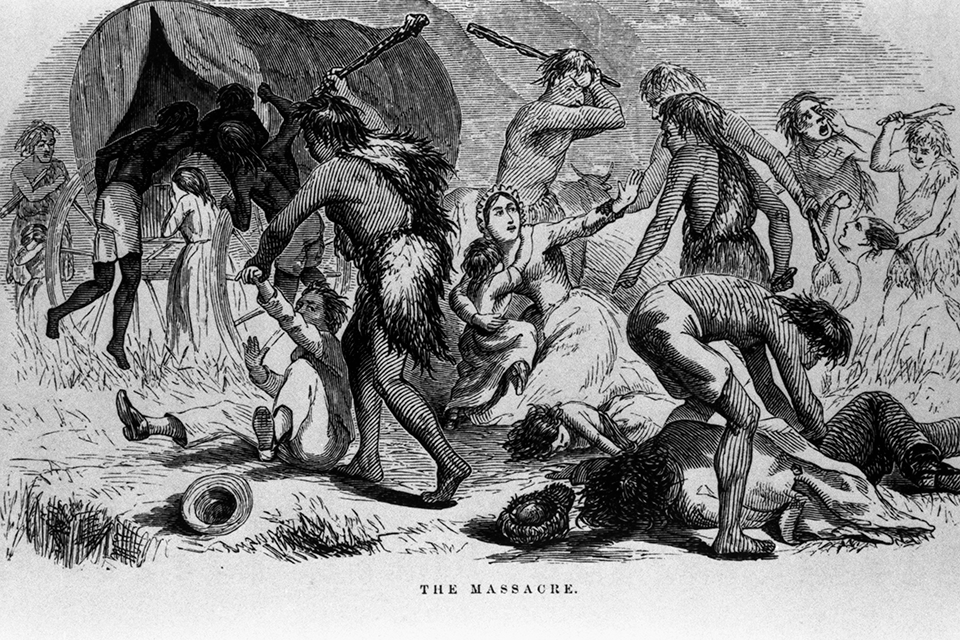

Apaches stole Herman Lehmann from his loving family and brutalized him, but he soon became a loyal tribesman, eagerly raiding former neighbors, and several times refusing opportunities to return to his family of origin. Why? What caused Lehmann, left, and many other white abductees to come to prefer life among their abductors?

Scott Zesch wrestled with that question in The Captured, a book inspired by his great-great-great uncle, Adolph Korn. Abducted by Comanche in Texas in 1870, Korn became an ardent member of the tribe. Returned to his white family three years later, he never readjusted to white culture, ending his days as a cave-dwelling hermit. Zesch studied the cases of many Texas captives and found that “nearly all of them came to prefer the native people’s society once they’d stayed with them more than a year.”

After the initial brutality of abduction, Zesch noted, Indians treated captives well. “The Comanche and Apaches not only received the child captives warmly and without prejudice; they also spent much time training them, making them feel significant in a tribal society.” For many captives, particularly adolescent boys, life among Indians was simply more fun than a diet of endless chores on a hardscrabble farm. “Ironically, captivity opened up a new world of freedom for some overworked farm children, who had previously spent their days herding livestock or hauling rocks or hoeing fields,” Zesch wrote. “With the Indians, they were allowed to ride horses, hunt, travel, loaf and play games.”

In The Searchers, his book on the classic John Wayne movie and the true story of the abduction that inspired John Ford to make the film, Glenn Frankel concluded that the Comanche had an ingenious means of assimilating captives. “A team of modern psychologists could not have dreamed up a more thorough method for absorbing a young person into the tribe,” Frankel wrote. “After being brutalized by his or her immediate captors and spirited north on a harrowing journey, the captive would be turned over to a family that oftentimes had lost a child of its own and treated the new addition with kindness and affection. Within a matter of months, the young person would lose the ability to speak English, and memories of parents and families faded or were crowded out altogether by many kindnesses and new adventures.”

“These children were treated very well,” William Chebahtah, Comanche grandson of one of Lehmann’s closest Indian friends, wrote in his book Chevato. “They were thought of as family and that’s why they never wanted to leave. That’s why it was hard for Herman Lehmann to leave the Comanche culture and come back home.” —Peter Carlson