The newly installed administration of President Richard Nixon had gotten the message loud and clear from the POW/MIA wives that it had better take notice of their husbands’ plight. Right now. The women and their families were Nixon supporters and voters—at least for the moment—and the administration wanted to keep them in that camp.

Sybil Stockdale, wife of James Stockdale, a Navy pilot shot down in September 1965, was pleased to see the results of her January 1969 “telegram-ins,” her version of the sit-in used by other activists. She had urged wives and family members of men who were prisoners of war or missing in action to deluge the president with telegrams telling him to put the POW/MIA issue at the top of his agenda. Nixon received more than 2,000 telegrams.

Stockdale “was encouraged to be notified that a group from the Nixon administration in Washington was coming to San Diego (to the Naval Air Station Miramar Officers’ Club) on March 26 to talk to us about the prisoners and missing. What a change—they were actually coming to talk to us without our having to browbeat them!”

Attendance was restricted to wives and parents of the POWs and MIAs from the area. It was to be held on a “no publicity basis.” Under military guidelines during President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, the POW wives were not allowed to speak with anyone outside of their immediate families about their husbands’ personal history and military service. They couldn’t write to communist leaders or heads of state to plead for their husbands’ release. And above all, they were never to speak to the press. They were warned that any information they gave to newspapers, TV or radio might be used against them.

Stockdale noted in her diary that she told the invitees, “I cannot impress upon you enough that this is a privileged meeting and that all discussion pertaining to it should be carefully guarded.” Remnants of the “keep quiet” policy remained in her comments, but they were fraying and thin as old lace curtains.

Melvin Laird, Nixon’s secretary of defense, selected young Richard “Dick” Capen for the data-collecting mission. Capen had worked for Copley Press, a newspaper publisher in San Diego. Laird asked Capen to apply his listening and observation skills to the POW/MIA families in San Diego. Frank Sieverts, special assistant to the deputy secretary of state and a POW in the Korean War, accompanied him.

The POW/MIA wives and families had had enough of the Johnson administration’s vague directives and lack of response to their situation. Many of the women had been single parents for three to four years. Many had struggled financially, and all had suffered emotionally since their husbands’ shoot-downs.

“The Washington Road Show,” as the wives cynically referred to the representatives from the State and Defense departments, had to answer to 500 angry and frustrated Navy wives from the San Diego area, as well as Air Force and Marine wives from the Los Angeles area.

Wife after wife forced the representatives to confront the truth: The “keep quiet” policy was a failure. Stockdale, noting that there had been no mail from POWs since October, said to Capen: “We need a change of policy by our Government. Things are getting worse instead of better. There is less mail instead of more. We want our Government leaders to stand up and criticize the North Vietnamese for not abiding by the Geneva Convention.”

Stockdale and Karen Butler, wife of Navy pilot Phillip Neal Butler, shot down in April 1965, were tape-recording the meeting for Bob Boroughs, a naval intelligence officer. Stockdale and other wives had worked with him to send covert, coded messages to their husbands. The government departments all distrusted one another, so the only way for the Navy to get an accurate report was to spy on the meeting. (Boroughs probably did this without authorization.) The maverick intelligence officer had rigged the two ladies up with tape recorders and speakers, which Stockdale and Butler cleverly pinned to their bras.

After Stockdale spoke, she noticed that Capen kept staring at her. She worried about the tape recorder bulge in her bra—was it obvious? She also realized that her tape and Butler’s were running out. Stockdale held up a printed sign: WE NEED A RESTROOM BREAK, and Capen declared an intermission. The two women ran to the bathroom together, most likely giggling nervously, and flipped their tapes over to record the second half of the meeting. Other wives and parents got up and yelled some more.

Capen vividly remembered the women’s anger: “It was therapeutic, and we owed it to them. They needed to vent.” But the women knew the prisoners’ situation was deteriorating rapidly—their “venting” was a desperate cry for help before it was too late.

After returning to Washington, Capen continued his research. On a Defense Department weekend retreat in early May, he presented his findings to Laird. Capen had learned what some of the POW wives already knew: The men were being tortured and denied proper medical treatment, food, clothing and mail privileges. They were often not even identified as being POWs. After listening to Capen’s findings, Laird said, “By God, we’re going to go public.’” Capen and Laird made it their mission to encourage and sustain the Nixon administration’s focus on the POW/MIA issue while National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger simultaneously juggled delicate peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese.

Despite this breakthrough, the POW situation remained urgent.

On April 5, Stockdale wrote a very frank letter to Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Thomas Moorer’s executive assistant, admitting that she did not always display the self-control she exhibited in public. “At home I rant, rave, cry, throw dishes and hurl invectives at both Washington and Hanoi.” Stockdale also mentioned her “spies at the Pentagon” and her desire—indeed, requirement—that she meet with Nixon soon.

Stockdale was letting the Navy and the government know that she had power, influence, the ear of the POW/ MIA families and high-profile allies in Laird, Capen and Sieverts. Stockdale received a speedy reply assuring her that things were indeed moving in the direction she desired.

Early on Monday morning, May 19, Capen and Sieverts phoned Stockdale.

Capen did most of the talking, in an excited manner. “We wanted you to know that here in Washington, in just a few minutes, the secretary of defense is going to do the thing you’ve been wanting him to do for so long. He’s going to publicly denounce the North Vietnamese for their treatment of the American prisoners and for their violation of the Geneva Convention.”

Stockdale thought, “That was a real switch . . . The administration was publicly abandoning the ‘keep quiet’ policy as its predecessors should have done years before.”

In his press release and televised address, Laird stated: “The North Vietnamese have claimed that they are treating our men humanely. I am distressed by the fact that there is clear evidence that this is not the case . . . The United States Government has urged that the enemy respect the requirements of the Geneva Convention. This they have refused to do.”

Laird ticked through the list of North Vietnam’s war crimes, including its leaders’ refusal to provide a list of imprisoned and missing men; treat and release the sick and injured Americans; allow the free exchange of mail between prisoners and their families; and allow the inspection of the prisoner camps by an impartial organization such as the Red Cross.

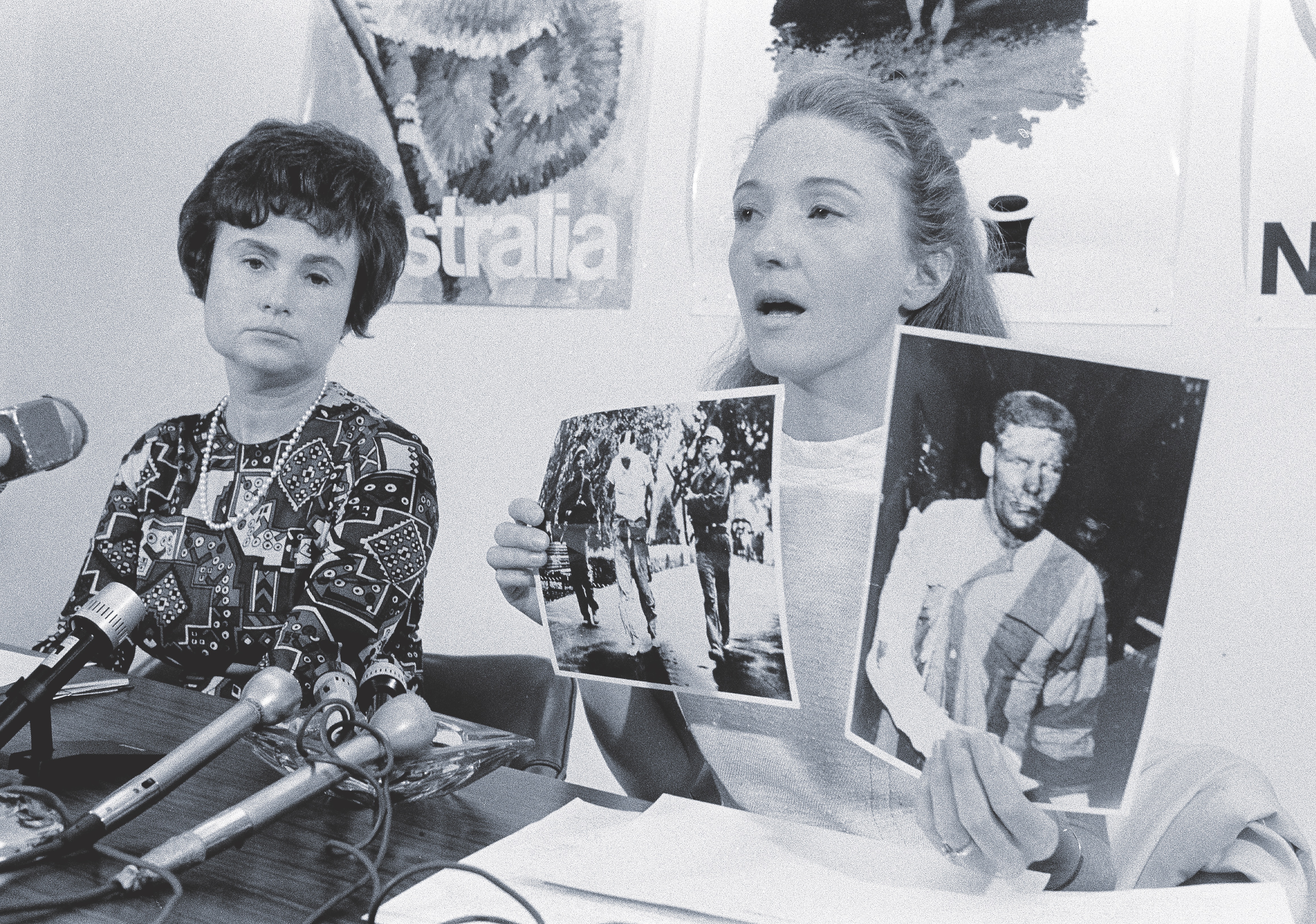

Even more affecting were the graphic photos Capen distributed to the press. Obtained on the black market in North Vietnam, they showed prisoners with injured and atrophied limbs, and men in solitary confinement. It made only a minor splash in the American media at first, but the ripple effect in the wider world was significant. In honor of July 4, the North Vietnamese decided to release three POWs.

As Stockdale readied for her annual sojourn to Sunset Beach, Connecticut, she got a call from Butler, whose sister had a contact with the West Coast editor of Look magazine in Los Angeles and arranged an appointment for the two POW wives on June 20. Look, which published short articles and lots of color photos, featured John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Mia Farrow, and the Smothers Brothers on its covers in 1969.

Butler and Stockdale spent more than an hour talking to Look’s editor about the POW mistreatment. He seemed empathetic but a bit bored. Stockdale was distraught. As she and Butler gathered their things to leave, the editor asked where he might get in touch with them if the magazine decided to run something. He was told to contact the secretary for the League of Wives of American Vietnam Prisoners of War, a San Diego organization formed by Stockdale in October 1967 to bring together POW wives on the West Coast.

Flying home to San Diego that evening, Stockdale and Butler had an epiphany. Stockdale wrote in her diary: “We reasoned that we needed a national organization if we were going to get national publicity.” They had already worked together with women all over the country for the telegraph-ins to the new president as well as to the Vietnamese embassy in Paris. Letter-writing campaigns were taking place all over the country. Now, Stockdale felt, “all we really needed was a name. On the airplane that day we decided to call ourselves ‘The National League of Families of American Prisoners in Southeast Asia.’ We felt the MIAs were implicit in this group, and Karen and I agreed I would be the National Coordinator.”

Later in July, Butler received a call from the Look editor, who declined to do an article on the POWs or even the San Diego League. The POWs had been adequately covered in Look and competitor Life magazine already, he explained. And the regional League might be better covered by a newspaper article. Butler’s heart sank, but then she “casually mentioned the National League. This was followed by a noticeable increase of interest in his voice. He asked if I would call him when the organization was completed.” They had found the key that unlocked their all-access press pass.

The National League, just an idea in the two POW wives’ minds a few weeks earlier, quickly became a reality. Soon the POW/MIA wives, led by Stockdale, would see themselves in Look, Reader’s Digest, The New York Times and Good Housekeeping, as well as local newspapers. Television interviews followed.

It didn’t hurt the wives that they represented the late-’60s traditional feminine ideal so well. The New York Times’ “Food, Fashion, Family, Furnishings” reporter took note of this. “The wives, for the most part, are slender, gracious and attractive. One man who met several of them described them as ‘pretty—like airline stewardesses.’ Some of them were stewardesses; Mrs. Tschudy, [Janie Tschudy, wife of Navy bombardier/navigator Bill Tschudy, shot down in July 1965] for example, flew for American Airlines for 10 months before she was married.”

In June 1969, Louise Mulligan, wife of Navy pilot James Mulligan, shot down in March 1966, was the first wife on the East Coast to go public, in Norfolk, Virginia’s Ledger-Star. Before she did so, she sat her six boys (ages 7 to 18) down and warned them that their lives were about to change. Her decision would affect them all and put them all into the same media spotlight the wives were stepping into.

Mulligan had a temperament well suited to speaking out. Like Stockdale, she was convinced that this was the only way to rescue their husbands from a terrible fate. Other Virginia POW/ MIA wives admired her for this, even if some of them were not as strident in their approach.

That same August, Phyllis Galanti, wife of Navy pilot Paul Galanti, shot down in June 1966, received a letter from Mulligan, explaining that she was the National League’s area representative. Mulligan wrote that she, along with Jane Denton, wife of Navy pilot Jeremiah Denton, shot down in July 1965, and Martha Doss, wife of Dale Doss, a Navy bombardier/navigator shot down in March 1968, had received letters brought back from North Vietnam by Rennie Davis, an anti-war activist and a leader in the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. “Mine was dated July 7th and sounded good,” Mulligan noted. “Says he’s gaining weight, hope so.”

Davis brought back, along with the mail, Navy Lt. Robert Frishman, Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Douglas Hegdahl and Air Force Capt. Wesley Rumble, who proved to be perhaps the most valuable sources of intelligence the Americans obtained during the war.

The more radical anti-war groups appeared to be North Vietnamese sympathizers, but many POW wives publicly acknowledged their growing dependence on anti-war activists. “Let’s face it,” Galanti said, “it’s too valuable a source to dismiss. It’s the only way I’m getting mail.”

In September 1969, Stockdale and five other National League members went to Paris to meet with North Vietnamese representatives. Stockdale had written to U.S. officials to reassure them about the group’s intent: “Our trip should in no way be interpreted as reflecting discredit on our own government. However, we are going independently, and without government sponsorship.”

The wives had found over the years that any tinge of overt government control could quickly taint the group in the eyes of the media and American public. With aviation company Fairchild Hiller and Reader’s Digest as sponsors, the group left for Paris on Sunday, Sept. 28.

The six members of the delegation represented POWs or MIAs from each branch of the armed forces. The group included one black member, Andrea Rander, wife of Army Sgt. Donald Rander, captured in February 1968, near Hue during the communists’ Tet Offensive. She was also the only wife whose husband was an enlisted man. He was among the small percentage of POWs who were African American, Army and enlisted men.

It was the difference in rank, not race, that concerned Rander. She recalled: “My experiences growing up in NYC allowed me to be very flexible and open about the race issue. . . I felt a little twinge because I was not the rank that the other women were.” Rander was intimidated—but only briefly—to be among older, more senior wives. “The common goal was that we were seeking information about our husbands,” she said. “This became more important than anything else as this trip developed.”

Once in Paris, the group checked into the InterContinental Hotel, a luxurious spot chosen for its superior phone service and proximity to the American embassy. The delegates dumped their bags in the plush lobby and began to plot strategy for the week.

Stockdale called each day for an appointment with the Vietnamese, and each day she was put off. The group was finally granted an audience at the North Vietnamese embassy on Saturday, Oct. 4. Stockdale was so nervous that day that “three times I went into the bathroom and had dry heaves as never before in my life. My whole digestive system seemed to be pushing itself way up into my throat.” Yet she felt a sense of calm when she finally entered the embassy. Stockdale wore a favorite bright-pink wool suit, bought in 1965 for her husband’s last change-of-command ceremony. Perhaps, she thought, it would bring her luck.

By now, Stockdale and her husband were deep into their covert communications work with Boroughs, and she was terrified that the North Vietnamese were on to her. Stockdale’s blood ran cold as Xuan Oanh, head of the North Vietnamese delegation, greeted her with “We know all about you, Mrs. Stockdale,” holding up a photo of her on the steps of the U.S. Capitol. “We know you are the organizer.” Well, thank God, she thought, At least they don’t know any more than that!

Each member of Stockdale’s delegation demanded information about their POW and MIA family members, and they delivered hundreds of letters of inquiry from others. They also drank gallons of tea and ate Vietnamese candies and French crackers, not daring to offend their hosts by refusing the refreshments.

Rander recalled the 2½-hour meeting as one long propaganda fest. “The women were questioned about their husbands, shown movies of napalm bombing and urged to participate in peace movements.” Before the group parted, the mood had lightened somewhat. Stockdale recalled: “We got the recipe for the candy, exchanged American cigarettes for Vietnamese cigarettes, and even took souvenir toilet paper from their bathroom.”

The Vietnamese provided no information of substance or real promises to help. What the delegation did receive was unintended: The publicity generated by the visit had once again put them and the POW/MIA issue in the spotlight. The worldwide media portrayed the Vietnamese as heartless and cruel—exactly the opposite of the image they wished to show to the world.

On Oct. 15, the New Mobilization Committee conducted a national anti-war protest, dubbed the October Moratorium. Hundreds of thousands of Americans protested in churches, schools and local meetings. Though the protests were mostly peaceful, Nixon was worried. The president decided he needed to comfort the country and tamp down the anti-war rhetoric.

On Monday, Nov. 3, at 9:30 p.m., in a televised address, Nixon reached out to his core supporters, famously dubbing them the “silent majority.” He also outlined his strategy for “Vietnamization,” Laird’s term for the plan to withdraw American troops while simultaneously training the South Vietnamese to defend themselves against the Viet Cong rebels in the South and the North Vietnamese Army.

The president “shifted the public perception, aligned himself with the patriots and identified the antiwar movement with the bombers and flag burners,” according to biographer Evan Thomas. A Gallup poll found that 77 percent of Americans supported Nixon’s view of the war.

But Stockdale fired off a telegram, rebuking Nixon for “not mentioning the plight of the prisoners in your message to the nation on November 3rd. I personally can understand the difficulty which mentioning them imposed for you. Many, however, cannot understand the deletion of their loved ones’ desperate plight from your message and have expressed their deep concern to me about not being able to meet with you personally.”

The following month Stockdale and more than 20 POW/ MIA wives and mothers were invited to Washington for a reception, coffee and press conference with the president. The officers’ club reception the evening of Dec. 11 was dazzling. The chiefs and secretaries of all the armed services, as well as the secretaries of defense and state, were there.

Recommended for you

The next day, Nixon spoke at a White House press conference. He and his wife, Pat, had spent the day with the 26 women (21 wives and five mothers) feted at the previous evening’s reception. These ladies represented the 1,500 women—mothers and wives—of American POWs and MIAs.

Five were invited to stand with Nixon for the press conference photo: Stockdale; Mulligan; Rander; Carole Hanson, wife of Marine pilot Stephen Hanson, shot down in June 1967; and Ann “Pat” Mearns, wife of Air Force pilot Arthur Mearns, shot down in November 1966.

Nixon began the press conference with the wives clustered around him like a phalanx of Amazon warriors: “I have the very great honor to present in this room today five of the most courageous women I have had the privilege to meet in my life.”

Stockdale stood next to him, nodding in approval, dressed again in her favorite bright-pink wool suit. There was no doubt that she had gotten her money’s worth out of that outfit.

On Feb. 12, 1973, following the January peace agreement in Paris that ended the war, the first group of freed POWs left their cells for home and the families they had not seen in years.

Heath Hardage Lee has worked at history museums across the country. She has a bachelor’s degree in history with honors from Davidson College and a master’s in French language and literature from the University of Virginia. She also wrote Winnie Davis: Daughter of the Lost Cause.

This article appeared in Vietnam magazine’s December 2019 issue.