Pan American Airways’ new Boeing 377 Stratocruiser was just beginning its descent into Tokyo on February 1, 1954, when a high-ranking U.S. Army officer approached the plane’s most celebrated passengers: Joe DiMaggio, the New York Yankees legend, and Marilyn Monroe, the famous Hollywood star and sex symbol, whom DiMaggio had married just weeks earlier. Speaking with a slight Texas twang, Major General Charles W. Christenberry, the assistant chief of staff at the army’s Far East Command, leaned over their seats to ask a question. “How would you like to visit Korea for a few days and entertain the American troops currently stationed in Seoul as part of the UN occupation force?” he asked.

“I’d like to,” DiMaggio replied, “but I don’t think I’ll have time this trip.”

“I wasn’t asking you, Mr. DiMaggio,” the general said. “My inquiry was directed at your wife.”

Monroe, a bit startled, looked up. “I’d love to do it,” she told Christenberry. “What do you think, Joe?”

“Go ahead if you want,” DiMaggio told Monroe. “It’s your honeymoon.”

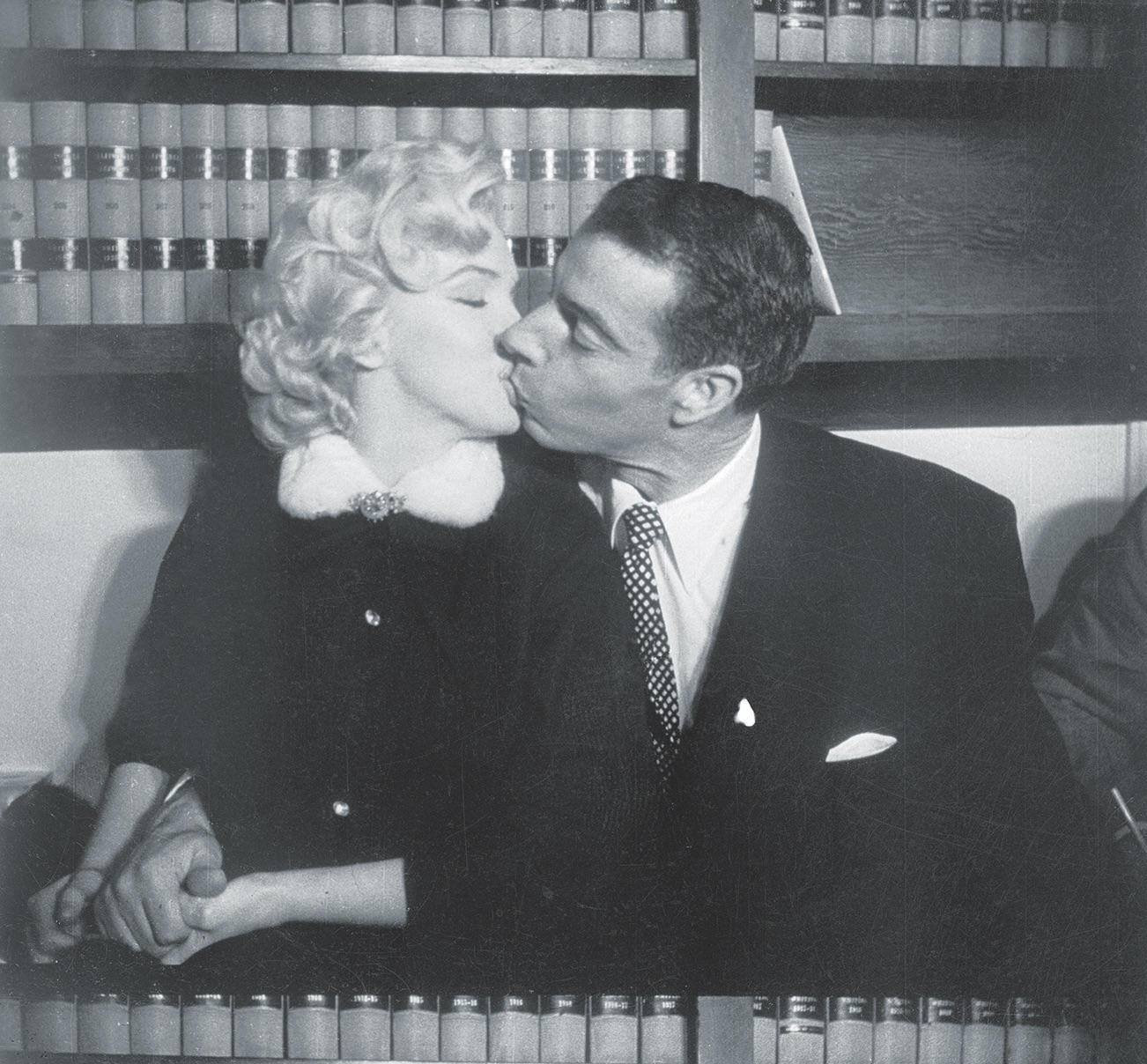

Actually, it was their honeymoon, and it had already gotten off to a rocky start. The couple had tied the knot in a civil ceremony at San Francisco City Hall on January 14, after two years of public, often volatile courtship. The former Norma Jeane Mortensen Dougherty had met her famous second husband on an arranged date in Los Angeles in 1952, when she was 25 and he was 37. Now, after years of paying her dues as

a low-billed starlet in Hollywood, Monroe was a red-hot celebrity, while the once-treasured “Yankee Clipper” was fading fast, having walked away from the game three years earlier after a stellar 13-season career patrolling center field in Yankee Stadium. Although neither wanted to admit it, even to themselves, they were moving in opposite directions—fast. Monroe’s whirlwind visit to Korea, as it turned out, only hastened that process.

On the surface, DiMaggio and Monroe seemed to be the perfect couple. Both could stop traffic on New York’s Fifth Avenue simply by walking down the street. Restaurants hushed when they entered. But DiMaggio had a reputation among those who knew him for being moody and self-obsessed. The son of Old World Sicilian immigrants, he wanted a doting wife to come home to, someone like his mother and two sisters. Monroe, the daughter of a mentally ill mother, had been passed around often abusive orphanages and foster homes. Unloved and unwanted as a child, she craved love, attention, and public affection. Her career was taking off, even as her new husband was attempting to restrict the type of films she could appear in and putting the kibosh on her sexy attire. (For just that reason she had turned down a juicy part as a schoolmarm turned burlesque dancer in the upcoming movie The Girl in Pink Tights.) Though neither DiMaggio nor Monroe could see it, his attempts to control her career doomed their marriage from the start. Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons predicted as much. “They must resign themselves to the fact that it can’t ever be a completely normal union,” she wrote. “Marilyn will remain in show business and Joe will not be able to take it.”

Monroe pooh-poohed the column. “It’s not like I’m giving up my career,” she told reporters. “I’m simply starting a new one.”

Fifteen days after their wedding, the newlyweds set off for Japan. Before their nuptials, DiMaggio had agreed to accompany an old friend and mentor, ex–major league baseball player Frank “Lefty” O’Doul, to coach and train Japanese baseball teams for the coming season. O’Doul was known as “Mr. Baseball” in Japan for his longtime support of the game there. DiMaggio would take Monroe with him; O’Doul, too, had recently remarried and was bringing his new wife, Jean. Like DiMaggio, O’Doul was a native San Franciscan. He had been DiMaggio’s first manager with the minor league San Francisco Seals, where he had famously announced that the best thing he could do for his budding young star was “change nothing.” The O’Douls were among the half-dozen people who attended DiMaggio and Monroe’s wedding. O’Doul thought the trip to Japan would be a perfect wedding gift for the happy couple. He meant well anyway.

DiMaggio and Monroe arrived to a swarm of fans and photographers at the San Francisco airport. Dressed in a matronly black suit partly offset by a sexy leopard-skin choker, Monroe tried to keep a taped and splinted right thumb hidden beneath her Maximilian “Black Mist” mink coat. When a sharp-eyed member of the press asked about her injury, Monroe replied, somewhat awkwardly, that it was nothing. “I just bumped it,” she said. “I have a witness. Joe was there. He heard it crack.” (Confidential accounts vary, claiming that the contact-averse DiMaggio had instinctively thrown back his right hand when Monroe came up behind him for a hug or else had thrown a glass of water at her during a quarrel. For what it’s worth, Monroe’s nickname for DiMaggio was “Slugger.”)

Just past midnight on January 29, the foursome boarded Pan Am Flight 831 for Tokyo (via Honolulu). The luxurious Stratocruiser, dubbed “the Flying Hotel,” featured a spiral staircase, single beds, and dressing rooms.

Nine hours later, during a short stopover in Honolulu, hordes of fans swarmed onto the tarmac outside the plane. DiMaggio tried his best to shelter his new bride from the public mayhem. But crazed fans tore at her dress and even pulled at her newly dyed bright-blonde hair. Monroe, United Press International reported, had enjoyed “the most enthusiastic greeting for a movie star in years.” That was one way of putting it.

Their arrival in Tokyo set off a new round of bedlam. Thousands swarmed the airport to catch a glimpse of the blonde beauty, knocking over photographers, airline officials, and policemen. Shouting “Mon-chan!”—Japanese for “sweet little girl”—the fans broke through barricades and smashed windows, forcing U.S. Air Force MPs to intervene. Monroe and DiMaggio had to squeeze through the plane’s cargo hatch to escape into a waiting car and speed to their hotel.

DiMaggio fully expected to be America’s most exalted celebrity in Japan, but it was Monroe the Japanese people came to see. At the hotel the adoring crowd would not disperse until she agreed to wave goodbye to them from a balcony—“like I was a dictator of something,” she complained. It didn’t help DiMaggio’s mood that some reporters had taken to referring to him as “Mr. Marilyn Monroe.”

At a joint press conference the next day, DiMaggio became livid when all the reporters directed their questions to Monroe, especially since many were impertinent and suggestive. “Do you sleep naked?” “Do you wear anything under your clothes?” “How long have you been walking like that?” Her answers: “No comment,” “I’m planning to buy a kimono tomorrow,” and “I started when I was six months old and I haven’t stopped yet.” More trouble came the following day when a formal invitation arrived from General John E. Hull, the head of the Far East Command, reiterating General Christenberry’s earlier request that Monroe visit Korea to entertain the troops. With DiMaggio and O’Doul likely to be tied up for days preparing the teams in Japan’s Central League for the upcoming season, Monroe thought the visit was a grand idea.

For Monroe, the trip to Korea would represent a grateful repayment of her debt to the thousands of American enlisted men overseas who had showered Hollywood studios with fan letters begging them to put Monroe in more prominent roles. Many of the GIs had never actually seen a Marilyn Monroe film, having been on active duty during her rise to stardom, but they knew her through myriad photographs, especially her nude calendar poses and her appearance on the cover of the premiere issue of Playboy magazine in December 1953, which was hard to come by since the magazine was not sold on military bases. Her photos had replaced those of World War II pinup legend Betty Grable on barracks walls and inside footlockers; Stars and Stripes, the U.S. Army’s newspaper, ran so many photos of Monroe that it had to begin reprising old ones.

The Korean War, which began on June 25, 1950, when 75,000 North Korean soldiers invaded South Korea, had subsided—it hadn’t officially ended—a few months before Monroe’s arrival in Japan. Three years of brutal combat had stopped without a formal peace treaty. (To date, none has ever been signed.) The United States had suffered 169,000 casualties in the fighting, including nearly 34,000 killed in action—a remarkably high percentage of KIA. One million American soldiers and marines continued to safeguard South Korea from reinvasion by the North. Monroe couldn’t visit them all, but she would see as many as possible.

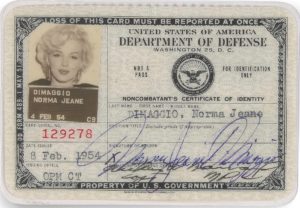

On February 8, Monroe received clearance papers and became a USO entertainer. (On her official I.D. card she was Mrs. Norma Jeane DiMaggio, Serial No. 129278.) Preparing like a trouper, with a short dress rehearsal at the Osaka Military Hospital in Japan, Monroe ran through songs with Corporal Al Guastafeste, an army pianist from Unionville, Long Island, and his musical group, Anything Goes. The 21-year-old Guastafeste marveled at the superstar’s lack of ego. “She was Marilyn Monroe, but she didn’t seem to realize it,” he later recalled. “If I made a mistake, she said she was sorry. When she made a mistake she apologized.” After rehearsing, Monroe took time to sign a cast for Corporal Donald L. Wakehouse of Iowa City, Iowa, a returning prisoner of war, and stretched out on the floor of the hospital to smile up at Private Albert Evans of Canton, Ohio, who was suspended upside down over his bed after breaking his back in a jeep accident.

On February 16, after they received vaccinations for cholera and yellow fever, Monroe and Jean O’Doul left Tokyo, escorted by U.S. Army entertainment officer Walter Bouillet. Arriving by helicopter in Seoul, Monroe looked radiant in a flight suit as she stepped out into the damp cold, with her blonde curls perfectly coiffed and a huge smile that could have melted the sun. One of the first enlisted men to see her was Ted Sherman, who had served in the navy during both World War II and the Korean conflict. “I was with a group of Navy guys who happened to be at Daegu Air Force Base when we heard Marilyn would entertain there that night,” he later recalled. “We convinced our transport pilot to find something wrong with our R4D transport so we could delay the return flight to our ship in Tokyo Bay for that one night. The sight and sounds of Marilyn singing ‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend’ is a memory I still cherish.”

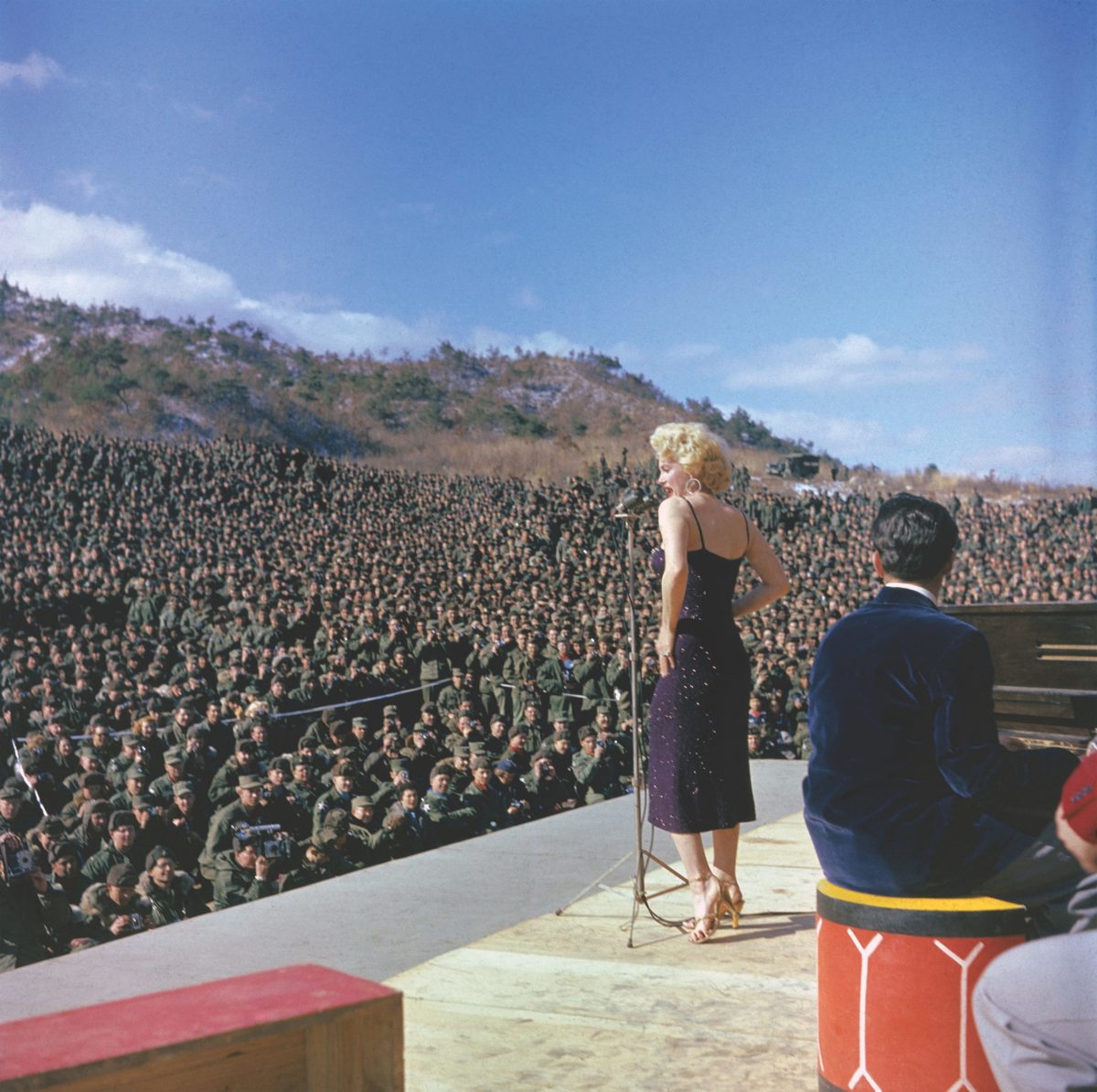

From Seoul Monroe’s USO entourage immediately set out for the 1st Marine Division camp in the remote and precipitous mountains outside the capital city. Swooping over the camp in their helicopter, Monroe could see thousands of marines crowding the slopes, looking up at her, waving, cheering, and whistling. She told the pilot to circle low so that she could wave back. Then, at great risk to her own safety, she had two soldiers slide open the door of the chopper and hold her by the feet as she lay on her stomach, leaning out the door and blowing kisses to the men below. The marines went wild.

Monroe’s offstage uniform consisted of clam-tight olive drab pants, an olive windbreaker, and rhinestone earrings. Had she been wearing a garbage bag, the men would still have drooled. Once on the ground she changed into a plum-purple (some said lavender) cocktail dress, beneath which she wore nothing, and gold high-heeled sandals. (She would keep the spaghetti-strap dress as a memento for the rest of her life.) Emerging from behind a burlap curtain, she walked out alone onto the makeshift plywood stage to a standing microphone. Snow and sleet peppered the stage. Greeting the marines in her breathy, little-girl voice, she launched into “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” her signature song from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, her 1953 motion picture. A riot almost broke out when she segued into the come-hither George Gershwin tune “Do It Again.” The men whistled and hollered so much that a worried Walter Bouillet suggested Monroe alter the suggestive words from “do it again” to “kiss me again.” She agreed. “Just kissing,” she promised.

Whatever she sang, the soldiers’ reaction was the same. As Monroe would later tell Hollywood screenwriter and director Ben Hecht: “There were seventeen thousand soldiers in front of me yelling at the top of their lungs. I stood there smiling at them. It had started snowing, but I felt warm, as if I were standing in the bright sun. I’ve always been frightened by large audiences, but standing in the snowfall facing these shouting soldiers, I felt no fear for the first time. I only felt happy. I felt at home.” For a young woman who had never had a real home as a child, it was a particularly welcome feeling. “This is what I’ve always wanted, I guess,” she said.

First Lieutenant George H. Waple III, given the enviable task of looking after Monroe during her Korean tour, always remembered her as being a good sport. “Marilyn never complained,” he recalled. “She seemed to like the basic living arrangement. Her only quibble was with the weather. She hadn’t expected it to be so cold and snowy. I told her I could give her an electric blanket for her cot, but she declined. She also turned down a small electric space heater for the room, saying she didn’t want to be the cause of any concern I might have had for her welfare. She was unspoiled to the nth degree.”

Underscoring Waple’s point, on the flight to the port city of Busan, Monroe excused herself from sitting up front with the generals and colonels and went back to the rear to sit with the band. She made it a point to see that her bandmates and at least 10 enlisted men were invited to every reception in her honor at an officer’s club. “Where I go, they go,” she said of the band. At one wild party at an officers’ club, Monroe accidentally sliced her wrist with a bayonet while trying to cut a cake. An army surgeon general was called in to treat the gash, and reporters were given strict orders not to report the incident. All in attendance had to surrender their photographs, which were immediately burned. The party, the base commander pointedly declared, had never taken place.

On another ice-cold day, Monroe performed at the Bulldozer Bowl—the USO’s stage in the Cheorwon Valley—for the U.S. Army’s 2nd Infantry Division. Soldiers claimed dibs on choice front-row seats seven hours before her performance. Wounded men from sick bay huddled in blue blankets while Monroe braved the chilly temperatures in her revealing summer dress, melting the hearts of the battle-hardened soldiers, many of whom had hiked several miles over frozen mountainous terrain to see her. It was worth the effort. “Marilyn came out dressed in a heavy parka,” recalled Don Loraine, who was in the audience. “She started to sing, suddenly stopped, and said, ‘That’s not what you came to see,’ and took off the parka. She was dressed in a low-cut purple cocktail dress. She was so beautiful, we all went wild, and, I might add, it was colder than hell that day. She brought a lot of joy to a group of combat-weary marines, and I for one will never forget her.”

After the concert Monroe posed for the hundreds of eager fans who crammed the stage. One GI was so flustered that he forgot to remove the lens cap from his camera. “Honey, you forgot to take it off,” Monroe said, removing the cover for him. All available film sold out in army PXs throughout Korea, and so many flashbulbs went off at her performance for the 7th Division that “the Reds probably thought the 7th Infantry Division was on night maneuvers,” one journalist wrote. “The sky kept lighting up from the constant flashing of bulbs as cameras clicked.” In the division’s mess hall afterward, Monroe stopped to eat two cheese omelets, her preferred meal, and noticed a blank spot on the wall behind her. Thinking it might embarrass her, soldiers had removed her ubiquitous “Golden Dreams” calendar, which featured some of the same nude shots of her that had run in Playboy a couple months earlier. But when Monroe spotted one calendar that the men had overlooked, she said, “I’m very pleased to have my picture hanging in a place of honor.”

When another performance was delayed, the troops, crammed in a crowd that stretched a mile long, threatened to raise hell. “I’ve never seen so many men in my life,” Monroe said, overwhelmed by their enthusiasm. For a better view she was lifted onto a tank surrounded by soldiers, posing and waving for all to see. She felt comfortable enough to push through a traffic jam of GIs who hadn’t laid eyes on an American woman for what felt like an eternity. Now they had one of the most gorgeous women in the world singing to them. Signs along the way cautioned troops: “Drive carefully—the life you save may be Marilyn Monroe’s.” Good-naturedly, she posed for a publicity shot with two 25th Division baseball players, wearing a team jacket and hat and holding a bat. She signed each autograph, “Love and Kisses, Marilyn Monroe.”

Monroe’s audience at the K-2 Air Base at Daegu consisted of 10,000 Dutch, Thai, and American troops. “She gave us the feeling she really wanted to be there,” recalled Ted Cieszynski, a photographer for the public information office of the Army Corps of Engineers. “Of all the performers who came to us in Korea—and there were a half dozen or so—she was the best. She showed no nervousness and wasn’t anything like a dumb blonde. When a few of us photographers were allowed to climb up on the stage after her show, she was very pleasant and cooperative and told us how glad she was to be with us. She took her time, speaking with each of us about our families and our hometowns and our civilian jobs. It was bitter cold, but she was in no hurry to leave. Marilyn was a great entertainer. She made thousands of GIs feel she really cared.”

Monroe was at her peak in Korea—confident, spontaneous, and heartbreakingly beautiful. She did it all on her own, without the often critical direction of her paid Hollywood handlers or overbearing husband. Following her last show, for the 45th Division, she blew kisses to the audience for a solid half-hour while the men cheered and applauded. “This is my first experience with a live audience, and my greatest experience with any kind of audience,” she told the crowd. “It’s been the best thing that ever happened to me. I’ll never forget my honeymoon—with the 45th Division. Come see me in San Francisco.” With tears in her eyes, she climbed aboard the helicopter to leave, calling out a last farewell: “Goodbye, everyone. Goodbye, goodbye—and God bless you all. Thank you for being so nice. Hold a good thought for me.” For the 100,000 bored and lonely soldiers she had entertained so selflessly in four whirlwind days of nonstop touring, she didn’t even have to ask.

Monroe’s tour in Korea had been an unqualified success, even though she came down with a bad case of bronchial pneumonia from her exposure to the icy conditions there. Those four carefree days not only lifted the spirits of the thousands of homesick young soldiers who saw her but also gave Monroe the genuine outpouring of love she had always craved. Her one-woman performances revealed her true talents and warm personality. “I never really felt like a star,” she told her acting coach, Lotte Goslar, after she returned to the States. “Not really, not in my heart. I felt like one in Korea. It was so wonderful to look down and see all those young fellows smiling up at me. It made me feel wanted.”

After landing in Tokyo, an exuberant Monroe shared her feelings with her husband. “It was so wonderful, Joe,” she said. “You never heard such cheering!”

“Yes, I have,” he replied, accurately if ungraciously.

But Monroe’s brief, wondrous trip to Korea turned out to be the beginning of the end of her marriage to DiMaggio. Over the next year and a half the gap between the two of them widened by the day. Ultimately, it was the famous subway grate shot on Lexington Avenue in New York City for Monroe’s next movie, The Seven Year Itch, that was the last straw for DiMaggio, who was on location with her that day. When Monroe’s silky white skirt blew over her head in full view of thousands of bystanders, DiMaggio “had the look of death on his face,” according to Billy Wilder, the film’s director. DiMaggio retreated to Toots Shor’s Restaurant to drown his sorrows. Two weeks later the marriage was over; Monroe filed for divorce. She was genuinely sorry, as she had been after the failure of her first marriage, but this time at least there was one great consolation: She would always have Korea.

Liesl Bradner, a California-based journalist, is the author of Snapdragon: The World War II Exploits of Darby’s Ranger and Combat Photographer Phil Stern (Osprey Publishing, 2018).