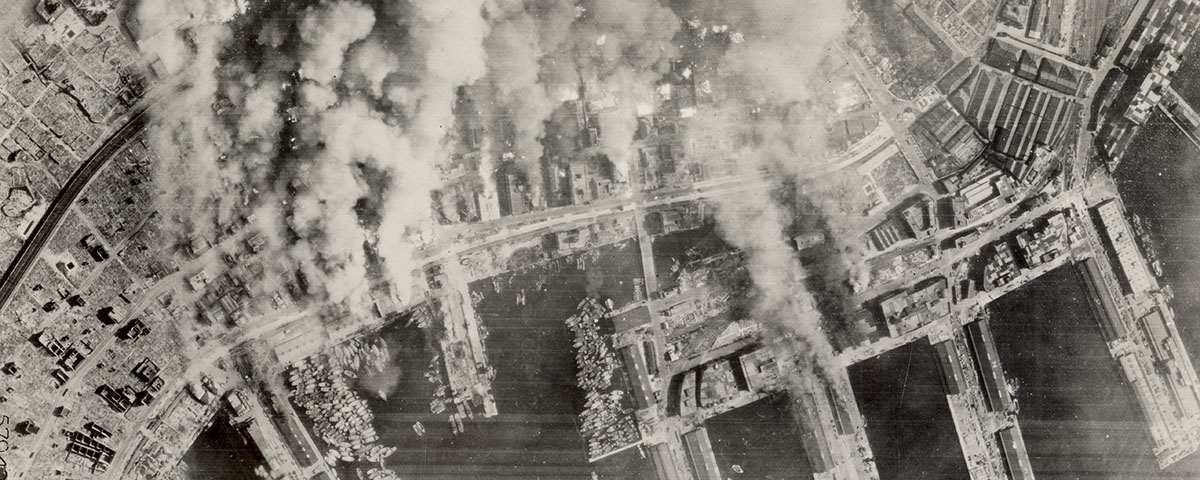

On the night of March 9-10, 1945, U.S. Twentieth Air Force B-29s burned down 7 percent of Tokyo and killed some 85,000 people. Probably no one on Major General Curtis LeMay’s staff in the Mariana Islands expected the Japanese to capitulate in the aftermath, but the unprecedented fire blitz on the enemy capital would set the standard for five months of operations to come.

By the summer of 1944, four B-29 groups were operating from India, staging through China within maximum range of southern Japan. LeMay, Army Air Forces chief Henry “Hap” Arnold’s troubleshooter, turned the hard-pressed XX Bomber Command around, improving efficiency and results. But the Asian mainland proved too demanding logistically, and late that year Superfortresses began flying from the Marianas, 1,500 miles south of Honshu. The emperor’s war machine was caught in a geographic vise that permitted no escape.

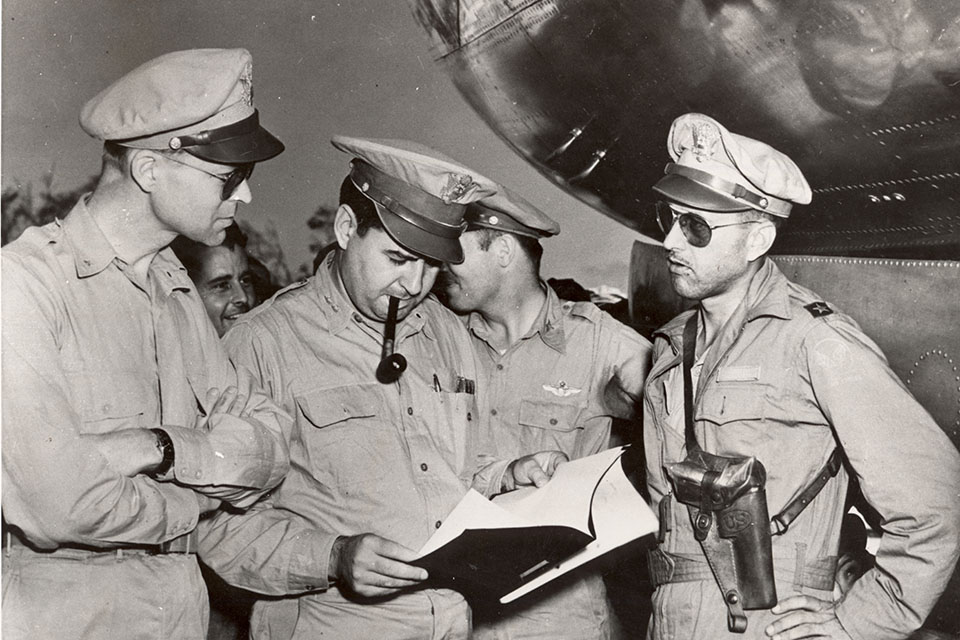

Now commanding XXI Bomber Command on Guam, LeMay concluded that conventional high-level bombing was not producing the desired results. Therefore, in early March 1945 he opted for a dramatic reversal of airpower doctrine. He sent hundreds of Superfortresses against Tokyo armed with incendiary bombs, at low level—at night.

The March 9 mission was code-named “Operation Meetinghouse.” Of 325 B-29s airborne that evening, 279 unloaded 1,665 tons on the Tokyo urban area while 20 bombers diverted to alternates. The fuel saved by stripping guns from most B-29s and cruising at lower altitudes had doubled the February ordnance average to nearly 6 tons per bomber.

Approaching the Japanese coast beneath a quarter moon, B-29 crews tugged on flak vests—heavy, cumbersome garments with steel plates that could stop a shell splinter. Some also donned helmets that interfered with earphones, but the airmen were flying into the enemy’s most cherished airspace at a frighteningly low altitude.

The primary target was a section of downtown Tokyo measuring three by four miles, recalled by historian John Toland as “once the gayest, liveliest area in the Orient.” Though wartime shortages had closed most businesses, the area teemed with life: an estimated 750,000 workers crammed into 12 square miles of low-income housing and family-operated factories. It was probably the most densely populated place on earth.

The sirens blared at midnight, but evidently few Japanese were concerned. They were accustomed to repeated alerts, mostly annoying false alarms. Furthermore, radio reports only mentioned American aircraft orbiting at Choshi, a port city 50 miles northeast—seemingly no immediate threat to the capital.

Choshi was one of the coast-in points for XXI Bomber Command B-29s.

The first bombers were pathfinders, sweeping in low and fast over Tokyo, doing nearly 300 mph at 5,000 feet. Their navigators had worked to perfection with an identical time over target of 12:15 a.m. Approaching at right angles to each other, the B-29s opened their bomb bay doors and the bombardiers toggled their loads. Bundles of incendiaries spewed into the slipstream, cascading onto the urban congestion. As the napalm sticks ignited, they formed a fiery cross on the ground.

The pathfinders did their work well, marking targets for the following bombardiers. Among the best work was the load that marked the Tokyo Electric Power Company. The firebombs seared the buildings, which were engulfed in flames, providing an almost unmissable aim point.

For the trailing bombers, X literally marked the spot. Each group and wing had designated target areas, as mission planners had divided the sprawling city into fire zones to avoid excessive concentration in one locale. Attacking between 4,900 and 9,200 feet, 93 percent of the B-29s struck the briefed urban-industrial area. As LeMay had predicted, the defenses were wholly saturated. Searchlights swept their pale white arcs skyward, occasionally illuminating a passing bomber, but seldom long enough for flak gunners to draw a bead.

It was Major Arthur R. Brashear’s tenth mission. The 499th Bomb Group’s target was the First Fire Zone between the Ara and Sumida rivers. His navigator’s notes summed up most fliers’ reactions to the defenses: “Night incendiary at 5,000 ft. Caught in lights for a short time. All kinds of flak, mostly inaccurate. No hits but this one had us scared!”

Almost half a million M-69 firebombs cascaded down from the night sky, and wherever they hit they spurted their napalm-filled cheesecloth bags. In a matter of minutes thousands of small fires from the little “fiery pancakes” were swallowing everything they touched, coalescing and swelling into a roaring conflagration unlike anything man had previously inflicted upon man.

A Vichy French journalist reported on the scene: “Bright flashes illuminate the sky’s shadows, Christmas trees blossoming with flame in the depths of the night, then hurtling downward in zigzagging bouquets of flame, whistling as they fall. Barely 15 minutes after the beginning of the attack, the fire whipped up by the wind starts to rake through the depths of the wooden city.”

As the sky over the city became superheated, huge amounts of air were sucked upward through multistory buildings in the “stack effect,” draining the cool air from ground level to feed the insatiable stack. As more and more ground air was drawn into the conflagration from farther afield, the firestorm spread of its own accord.

A fully developed firestorm is a horrifically mesmerizing sight. It seems like a living, malicious creature that feeds upon itself, generating ever higher winds that whirl cyclonically, breeding updrafts that suck the oxygen out of the atmosphere even while the flames consume the fuel—buildings—that feed the monster’s ravenous appetite. Most firestorm victims do not burn to death. Rather, as carbon monoxide quickly reaches lethal levels, people suffocate from lack of oxygen and excessive smoke inhalation.

In Tokyo that night some citizens felt that hell had slipped its nether bounds and raised itself through the earth’s crust to feed on the surface. People fled panic-stricken from searing heat amid the demonic roar of flames, the crash of collapsing buildings and the milling congestion of terrified human beings. Some survivors found themselves suddenly naked, the clothes burned off their bodies, leaving their skin largely intact.

In those frightful hours humans watched things happen on a scale that probably had never before been witnessed. The superheated ambient air boiled the water out of ponds and canals while rains of liquid glass flew, propelled by cyclonic winds. Temperatures reached 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, melting the frames of emergency vehicles and causing some people to ignite in spontaneous combustion.

Decades of Japanese unpreparedness and complacency took a terrible toll, with barely 8,000 firemen to cover an area of 213 square miles. There were insufficient shelters and, perhaps worse, too few fire lanes to prevent one conflagration from spreading into another. Even adequate firebreaks might not have helped that night. The bombers possessed an invincible ally in the form of stiff southeasterly winds that whipped and whirled burning embers from one neighborhood to another. Wherever the fiery brands landed, they spread the flames uncontrollably.

Tokyo’s fire department fought a losing battle from the first few minutes. The fire chief spent a horrible night dashing from one area to another, trying to coordinate his insufficient resources. His sedan caught fire twice.

The firemen were gallantly ineffective with their towed water carts and hand pumps—poor substitutes for firetrucks, many of which stalled in the chaos and, immobilized, melted into the street. Nearly 100 fire engines were incinerated with hundreds of personnel. Those numbers, pitifully small within the context of the greater catastrophe, further emphasize Tokyo’s woeful unpreparedness. It was no better in residential areas, where the burden fell upon thousands of pitifully prepared neighborhood associations. Small groups of families tried to comply with government dictates to swat at fires with dampened cloths or sandbags, or vainly attempted to douse blazing napalm with buckets of water.

Everywhere people were forced to rely on their own meager resources. Factory worker Hidezo Tsuchikura saved his family and himself by climbing into a water tank on a school roof. Tsuchikura later made a Dantesque comparison: “The whole spectacle with its blinding lights and thundering noise reminded me of the paintings of purgatory—a real inferno out of the depths of hell itself.”

Not even the imperial bunker was immune. When the firestorm’s high winds dropped burning embers onto the emperor’s Obunko, shrubs and camouflage material ignited. Palace guards and staff were reduced to subduing the flames using water pails and even tree branches.

Safely underground, Emperor Hirohito and Empress Kojun sat out the attack in their bunker. The empress had observed her 42nd birthday three days previously, and now they had planned on celebrating their grandson’s first. Instead they tasted the acrid outside air that slipped through the filters and vents.

Brigadier General Thomas Power’s B-29 had fuel to spare and circled the spreading inferno for 90 minutes, radioing a play-by-play of the growing catastrophe. Because post-strike photos would not be available for a day or more, the wing commander had cartographers on board to plot the extent of the fires for immediate assessment back at Guam. He noted that it took just 30 minutes for the first bombs to spread into a fully developed conflagration. Actually, it was half that time. On the ground, some witnesses reported that from the moment the first firebombs struck, only 14 minutes passed before “the hellfire began.”

A firestorm also could threaten the airmen who created it. Bomber crews over urban areas had to contend with wind shear as well as powerful thermals. The firestorms created violent cyclones and vertical winds that could toss 50-ton bombers onto their backs.

Captain Gordon B. Robertson and his 29th Group crew, who flew their first mission that night, received a terrifying initiation to combat. Caught by searchlights at 5,600 feet and nearly blinded by the glare, Robertson and his copilot fought to keep the wings level until “bombs away.” By then the attack was well developed, with incredible updrafts that lifted some B-29s 5,000 feet. The Superfortress felt, the pilot said, “like a cork on water in a hurricane.”

Abruptly Robertson’s bomber rolled, its wings tilted at an angle alarmingly past the vertical. Pilots and crew were conscious of a rain of debris inside the B-29: everything from sand and cigarette butts to oxygen masks falling from the floor. The fliers realized they were upside down. It was a chilling sensation to see the fiery world “below” suddenly appear through the top of the cockpit.

Robertson, an experienced flight instructor, oriented himself to the ground. In a maneuver more suited to a fighter, he allowed the huge bomber to fall nose-first through the bottom half of a loop, completing a split-S maneuver that compressed the crew into their seats under the onerous foot of gravity’s elephant. The B-29 accelerated rapidly, clocking 400 mph at the bottom—about as fast as a Superfort ever went. Fighting the heavy aerodynamic loads on the controls, Robertson expended much of his momentum to regain precious altitude.

About 90 American fliers died that night and at least six more later perished in captivity. Aircraft losses among the 299 effective sorties totaled 14 planes downed, ditched or demolished by enemy action or accident, including two crews lost in bad weather, three bombers ditched in the sea and one plane crash-landed on Iwo Jima. That equaled 4.6 percent, right in line with LeMay’s eerily accurate prediction of 5 percent.

The surviving B-29s turned southward with ashes streaked on their glass noses and appalling odors sucked inside the fuselages. Though they were flying well below the standard 10,000 feet for oxygen bottles, some men strapped on their masks to escape the stench of burning flesh.

In the aftermath, Tokyo’s survivors struggled to deal with the massive calamity and found no standard of comparison. Medical services were reduced to insignificance: The only military rescue unit in the capital numbered nine doctors and 11 nurses. Not even the capital’s combined civil and military emergency services could ease human suffering on such an unprecedented scale.

“Stacked up corpses were being hauled away on lorries,” Fusako Sasaki recalled. “Everywhere there was the stench of the dead and of smoke. I saw the places on the pavement where people had been roasted to death. At last I comprehended first-hand what an air raid meant.”

American intelligence monitored a Japanese radio report that said: “Red fire clouds kept creeping high and the tower of the Parliament Building stuck out black against the background of the red sky. During the night we thought the whole of Tokyo had been reduced to ashes.”

Spread by panic-driven rumor, exaggerated Japanese accounts of the disaster claimed as much as 40 percent of the city had been destroyed. In truth, 7 percent of metropolitan Tokyo—16 square miles—had been razed that night. But with that level of destruction inflicted in less than three hours, the capital could well be completely leveled in two weeks of continuous operations.

The grimmest measure of Meetinghouse’s effectiveness was found in a single astonishing number. During 10 previous attacks since November, Tokyo had sustained fewer than 1,300 deaths. Then, literally overnight, at least 84,000 were killed and 40,000 injured. (Reports of 100,000 dead probably included displaced persons unaccounted for.) More than a quarter-million buildings were destroyed, leaving 1.1 million people homeless.

Damage to Japan’s industry was considerable. The 16 facilities destroyed or badly damaged included steel production, petroleum storage and public services. And no one could calculate the number of small feeder factories and family shops that had been incinerated in the residential areas.

One of the most illuminating comments on Meetinghouse came from Maj. Gen. Haruo Onuma of the Japanese army general staff: “The effect of incendiary bombing on the capital’s organization and the disposition of factories of Japan was very great, and, accompanying this, the main productive power was stopped. It [also] decreased the will of the people to continue the war.” Tokuji Takeuchi of the Ministry of Interior echoed that from a civilian perspective: “It was the great incendiary attacks on 10 March 1945 on Tokyo which definitely made me realize the defeat.”

LeMay’s fire blitz continued two nights later, with 310 bombers over Nagoya. The atmospheric conditions were far less favorable than at Tokyo, however, and the many initial fires never merged into a mass conflagration. About two square miles were burned.

The next night, March 13, was Osaka’s turn. A cloud deck forced most planes to drop by radar, but the incendiaries did their job, charring eight square miles of the industrial and port areas. Subsequent missions scalded Kobe on March 16-17 and Nagoya again on the 19th, each time with 300 or more B-29s.

The five incendiary missions constituted some 1,400 bombing sorties that razed or burned 30 square miles of urban-industrial area. The cost was 21 Superforts. Meanwhile, XXI Bomber Command stood down for a few days while the Navy delivered more bombs to replenish nearly empty bunkers.

The postwar Strategic Bombing Survey tentatively concluded that some 330,000 Japanese died in B-29 attacks within 14 months—the huge majority in six months. The actual numbers are unknowable, but for context the Anglo-American bombing offensive in Europe killed between 500,000 and 600,000 Germans in four years.

Pundits have claimed that the Meetinghouse raid killed more people than the atomic bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki, the death tolls from which remain controversial even today. But one thing is indisputable: The fire raids against Japan’s urban-industrial areas inflicted massive damage on a scale and efficiency seldom seen before or since.

Airpower had won its terrible, decisive victory.

Barrett Tillman is an award-winning historian with 50 books and nearly 700 articles published. His next book is a centennial history of aircraft carriers, due in 2017. Further reading: Tillman’s Whirlwind: The Air War Against Japan 1942-1945 and LeMay: A Biography; Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, by Richard B. Frank; and Blankets of Fire: U.S. Bombers Over Japan During WWII, by Kenneth P. Werrell.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!