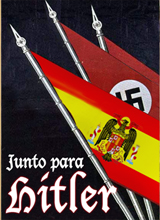

It is June 12, 1940. France is on the verge of defeat. Hitler appears certain to conquer Great Britain and win the war outright. Pleased with this development, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco rejects neutrality and announces a tacitly pro-German policy of nonbelligerence, modeled after that of Italy before its entrance into the war just two days earlier. On October 23, he signs an agreement committing Spain to join the Tripartite Pact—which Germany, Italy, and Japan concluded the previous month—at a time to be agreed upon by the four powers. Its terms assure Spain of badly needed military and economic assistance from Germany and Italy, and the restoration of Gibraltar, which Britain had seized from Spain in 1713. It also promises an expansion of Spanish territory in Morocco at the expense of Vichy France.

It is June 12, 1940. France is on the verge of defeat. Hitler appears certain to conquer Great Britain and win the war outright. Pleased with this development, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco rejects neutrality and announces a tacitly pro-German policy of nonbelligerence, modeled after that of Italy before its entrance into the war just two days earlier. On October 23, he signs an agreement committing Spain to join the Tripartite Pact—which Germany, Italy, and Japan concluded the previous month—at a time to be agreed upon by the four powers. Its terms assure Spain of badly needed military and economic assistance from Germany and Italy, and the restoration of Gibraltar, which Britain had seized from Spain in 1713. It also promises an expansion of Spanish territory in Morocco at the expense of Vichy France.

Spain does join the pact. Then, on January 10, 1941, it declares war on Great Britain, a step timed to coincide with the start of Operation Felix, the Nazi plan to capture the British fortress at Gibraltar. Sixty-five thousand German troops cross from occupied France into Spain, and by February Felix gets seriously under way. At that juncture, Hitler curtly informs Vichy France that Spain will receive a portion of French Morocco. Spanish troops occupy the expanded territory without firing a shot.

The tiny Gibraltar peninsula—less than three square miles in size—comes under intense pressure from German infantry and armor, as well as relentless bombardment from heavy artillery and near-continual air raids. Within a month, the British garrison of 30,000 capitulates. The loss of Gibraltar closes the western Mediterranean to the Royal Navy, although British forces in the Middle East can still be supplied via the Suez Canal. Franco had urged Hitler to preempt this with an offensive to seize the canal, but Hitler, unwilling to adopt a Mediterranean-oriented strategy, declines to do so. His primary purpose in capturing Gibraltar was to strike a blow to British morale; furthermore, Franco’s entry into the war has made it possible to base German U-boats in Spanish ports.

The seizure of Gibraltar, however, fails to shake Britain’s resolve to continue the war. The United States, its foreign policy increasingly tilted toward Britain, ends trade relations with Spain, thereby forcing the diversion of substantial Axis economic resources to that country. Spain has planned to invade Portugal, but is incapable of doing so on its own. Hitler is uninterested in helping. Focused on Eastern Europe, he does not want to invest troops in a theater peripheral to German interests.

On June 22, 1941, Hitler invades the Soviet Union. The Falange, an organization of staunchly anti-Communist Spanish fascists, recruits a division of volunteers for service on the Eastern Front. Known as the Blue Division, its battlefield performance wins Hitler’s admiration; its commander, Maj. Gen. Augustín Muñoz Grandes, receives the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, an honor rarely bestowed on a non-German. As many as 45,000 Spaniards serve in the Blue Division, which suffers 13,654 casualties during its two years of service.

The above scenario closely fits the historical record. Spain did indeed declare nonbelligerent status, and did sign an understanding that it would eventually join the Tripartite Pact. As late as December 1942, Franco believed that at the right moment, Spain would join the war on the side of the Axis Powers. A Falangist Blue Division did serve on the Eastern Front until mid-1943. The number of casualties it sustained during that period is historically accurate, as is the name of its commander and the award he received.

The sequel to Spain’s entry into the war is more difficult to imagine, but one possible scenario is the following:

In November 1942, the British Eighth Army defeats the Afrika Korps at El Alamein and gradually pushes the Germans toward Tunisia. That same month, the British and the Americans launch Operation Torch against the southwestern coast of Spain, partly in order to satisfy President Roosevelt’s insistence that U.S. troops begin combat operations against Germany before year’s end, and partly to retake Gibraltar as a prelude to operations aimed at containing the Afrika Korps in Tunisia. With comparatively few Germans still in Spain—most have redeployed to the Russian front—the western Allies have little difficulty gaining a foothold, and recover Gibraltar in January 1943.

In May 1943 the British and the Americans land in northwest Africa. They easily seize Spanish Morocco, as well as the Vichy French ports of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. Although Hitler reinforces the Afrika Korps, British and American forces overrun Tunisia by October, capturing some 230,000 Germans and Italians.

The Allies then weigh their options—to expand their foothold in Spain, or invade Sicily. Since Italy is the more dangerous foe, they decide upon the latter course, followed by an invasion of southern Italy. They anticipate, correctly, that the stress of this disaster will result in the collapse of the Mussolini regime.

Franco believes himself certain to meet the fate of Mussolini if the war continues. Accordingly, he enters into negotiations with the western Allies, but to his consternation the Allies demand Spain’s unconditional surrender, as well as his own resignation. The Spanish officer corps, never enthusiastic about Franco’s adventurism, forces him to accede. Franco is soon afterward assassinated, whether by pro-Communist Republicans or Falangist diehards no one can say. The Spanish pretender to the throne, Don Carlos, is restored as monarch.

Although the above scenario is speculative, three things are virtually certain: Spanish belligerency would have yielded disaster for a country already ravaged by civil war; the Franco regime would not have survived; and the monarchy would have been restored—as some Spanish generals actually urged during the war and as did in fact occur upon Franco’s death in 1975.

Historically, both Germany and the Franco regime fully expected Spain to enter the war at some propitious time. But Spain required too much economic and military aid, while Germany demanded that Spain cede to it the Canary Islands and Spanish Equatorial Africa to support its submarine offensive. This Spain refused to do, though the disagreement might have been resolved simply by granting Germany basing rights. More serious—and ultimately a deal breaker—was Spain’s desire for an expanded colonial presence in Morocco. Germany agreed in principle to allocate part of French Morocco to Spain at the war’s conclusion. But Hitler’s refusal to offer specifics gave the Franco regime considerable pause.

With that said, Hitler was initially willing to grant Spain the territorial concessions Franco desired. He reversed himself when a combined force of British and Free French attempted to seize Dakar, a strategic port in French West Africa held by Vichy France, between September 23 and 25, 1940. Though the expedition was a fiasco, it convinced Hitler of the importance of retaining good relations with Vichy France as a bulwark against potential future Allied incursions. Had this minor event not occurred, it is likely that the Franco regime would indeed have entered World War II—with little effect on the conflict’s outcome, but with cataclysmic results for Spain.