From 1907 until 1947 Buffalo Soldiers, known for their exceptional horsemanship, taught classes of all-white cadets riding skills and tactics at the West Point Military Academy. Yet their contributions were little more than a footnote in the history of the academy until recently.

On September 10, the academy unveiled a new monument dedicated to the Black soldiers once stationed at West Point. Although the athletic grounds at West Point were renamed in 1973 to honor Buffalo Soldiers, the memorial to the actual men was on a large rock bearing a plaque.

To many, this tribute wasn’t sufficient.

Sculpted by Eddie Dixon, who served in the 101st Airborne in Vietnam from 1968 to 1970, the 10-foot-tall bronze statue is in the likeness of Sgt. Sanders Matthews, who passed away in 2016 and was the last known living Buffalo Soldier to serve at West Point from 1939 to 1962.

“When I was coming up we had no role models that we could talk to,” Dixon said at the unveiling. “We didn’t know we had Buffalo Soldiers.”

If we had known about that it would have made a difference. Now they have a historical, tangible reference point,” he added.

Established in 1866, a year after the Civil War ended, Buffalo Soldiers were formally known as the United States Army’s 9th and 10th Cavalry. Mainly known for supporting the nation’s westward expansion, Buffalo Soldiers “served at a variety of posts in the Southwest and Great Plains, taking part in most of the military campaigns during the decades-long Indian Wars –– during which they compiled a distinguished record, with 18 Buffalo Soldiers awarded the Medal of Honor,” according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Despite Buffalo Soldiers being renowned for their fighting abilities and superb horsemanship, the Army would remain officially segregated until 1948, forcing black soldiers like Matthews to live in segregated barracks at West Point. The men were tasked with menial labor in between their teaching duties.

“We were the only ones that cut ice for everybody on the post,” Matthews later recalled in an oral history. “No white soldier ever cut ice on the post, always Blacks.”

“It is one of those dichotomies that some of the best soldiers in our military were African American, and at the same time Jim Crowism and ‘separate but equal’ existed,” Ret. Col. Krewasky A. Salter, a former teacher of military history at West Point and the current executive director of the First Division Museum in Wheaton, Ill, told the New York Times. “They represented the hope, faith, resiliency and commitment to what African Americans could achieve.”

Presently, Black cadets make up 17 percent of West Point’s class of 2024, and 14 percent of West Point’s student body.

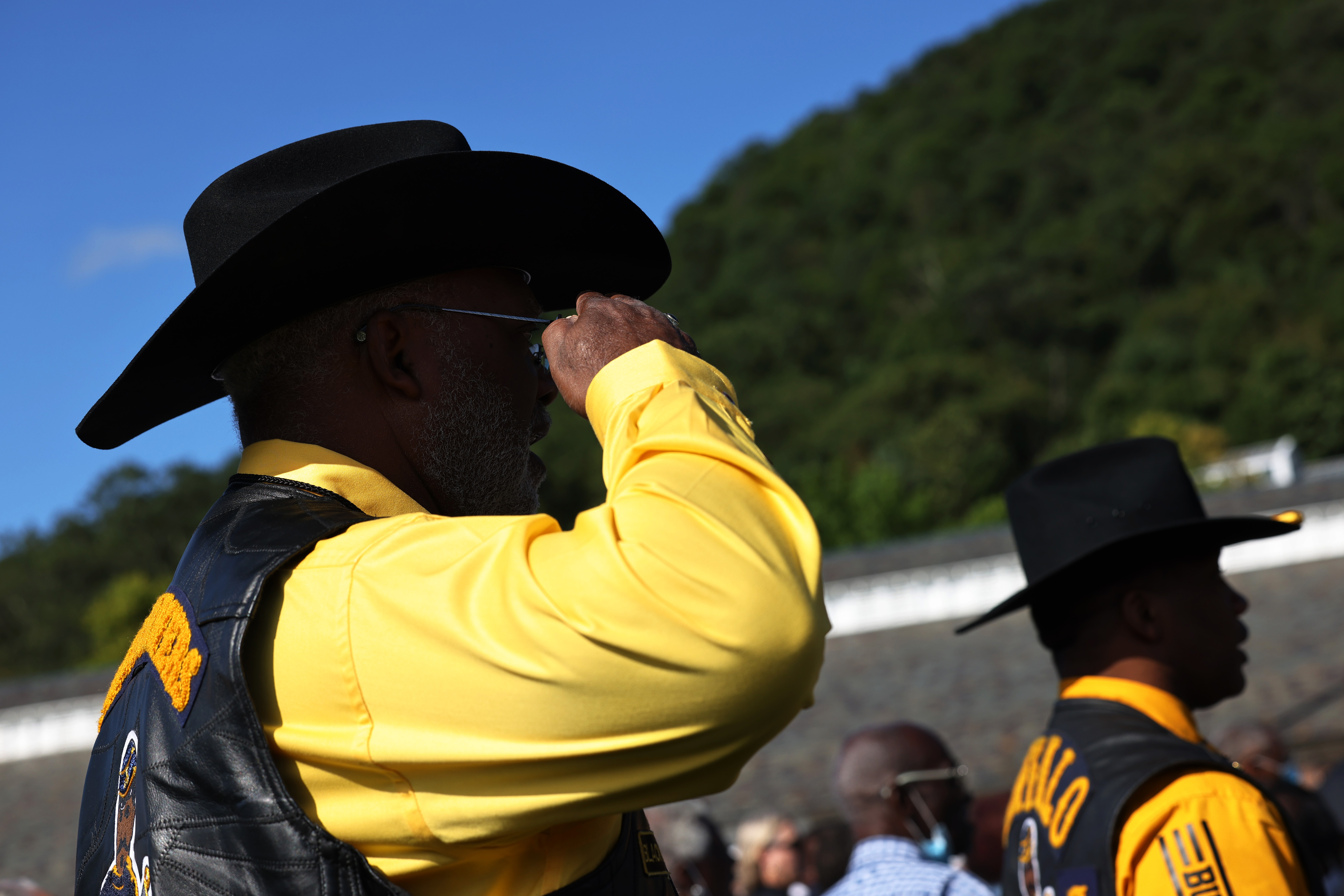

The unveiling of the monument on Friday was the culmination of a nearly five-year fundraising effort by the Buffalo Soldiers Association of West Point, which raised nearly $1 million for the statue.

“These Soldiers embodied the West Point motto of Duty, Honor, Country and ideals of the Army Ethic,” U.S. Military Academy 60th Superintendent, Lt. Gen. Darryl A. Williams said in a statement. “This monument will ensure that the legacy of Buffalo Soldiers is enduringly revered, honored and celebrated while serving as an inspiration for the next generations of cadets.”