ELIZABETH WILLING POWEL was an 18th-century Philadelphia socialite, a fixture in her hometown’s most influential circles, and a proto-feminist who delighted in her intellect, broad range of interests, and social rank. Powel came from a Quaker background that traced to great-grandfather Edward Shippen’s first marriage, to a woman who belonged to the Society of Friends. A portrait shows a buxom woman round of face, high of forehead, and receding of chin, solemn to the point of sadness but also resolute. Eliza Powel had a first-class mind, and, unusual among women of her class and era, a serious interest in and engagement with the details and nuances of politics and statecraft.

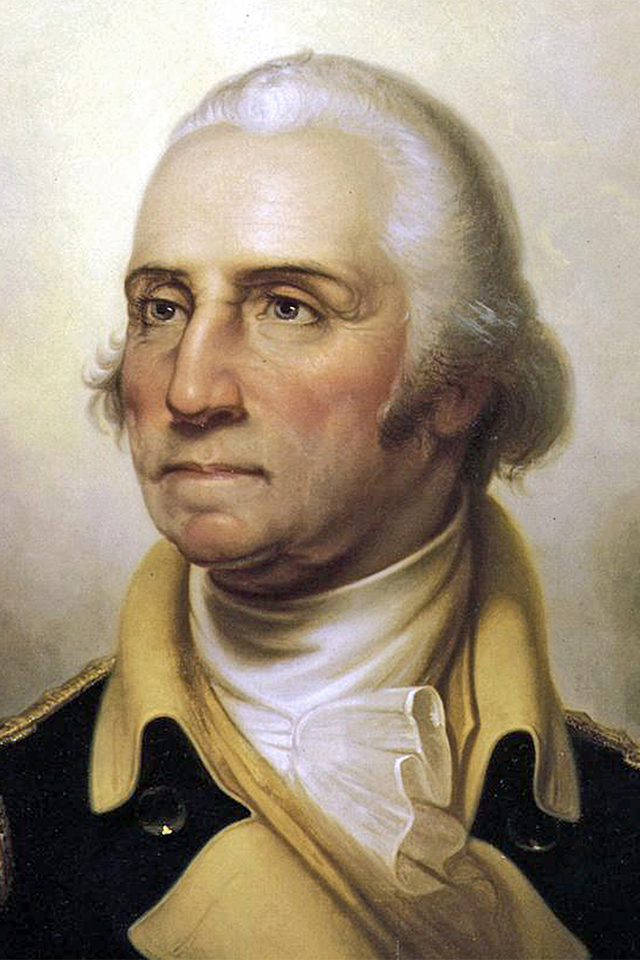

Eliza Powel and George Washington met in Philadelphia amid historic events in 1774. She was 31. He was 42 and, like her father, Charles Willing, a delegate to the First Continental Congress convening that autumn, bringing delegates from the restive colonies. Washington, who had left the British army to grow tobacco and wheat, was participating as one of Virginia’s representatives. Diligently pursuing useful contacts, the former soldier made friends with prominent Philadelphians, including the very social Mayor Samuel Powel and wife Eliza. Invitations to parties at the couple’s Third Street home had high status; during his four-month stay as a congressional

delegate, the Virginian became a frequent guest of the Powels.

That first encounter led to a friendship between George and Eliza that deepened, evolved, and endured through the Revolution, his presidency, and well into his retirement. She idolized him, and he looked upon her as a confidant and a sounding board. Eliza Powel’s influence on the first president approaches Abigail Adams’s on

the second—her husband, John. Abigail Adams, however, is a household name, whereas outside her home town and historians’ circles Eliza Powel is little known.

George Washington was no Don Juan, but he had his flirtatious side, much on display with Sally Fairfax, two years his senior and a friend since their adolescence. Sally was wed to Washington’s friend George William Fairfax. George Fairfax’s older cousin, Lord Thomas Fairfax, owned more than 8,000 square miles of Virginia and was one of the colony’s power figures. To go with beauty and sparkling personality, Sally Fairfax was bright, multilingual, and—catnip to the bibliophile Washington—well-read. The two began a vivid mutual flirtation, with a smitten Washington pushing by letter for greater, albeit unspecified intimacy—in historian Ron Chernow’s words in his 2010 biography Washington: A Life, “playing with fire in seeking a private correspondence with a married woman.” The object of those affections kept her would-be suitor at arm’s length, however, and in time the connection cooled into mature friendship, with George welcomed at Belvoir, Lord Fairfax’s manor, and Sally a guest at Mount Vernon, by now home to George and Martha Custis Washington, who married in 1759.

In some ways, the Sally Fairfax episode reads as a rehearsal for the relationship Washington developed and maintained with Eliza Powel: ambitious, ardent military man of parts encounters attractive, intellectually intriguing woman, otherwise attached yet still with a taste for the game and inclined to keep a chaste connection rather than break off contact. But while Sally Fairfax’s personal impact on Washington and his times remained social and personal, Eliza Powel’s reverberated in the public realm and into history itself.

In addition to corresponding, Eliza and George, over the years, met frequently in private, prompting speculation among subsequent generations of historians that this relationship may have progressed beyond close platonic friendship. Would Eliza Powel have been willing? Probably. How about George Washington? In correspondence with others, the general implied that he would not oppose an extramarital relationship provided he could avoid betraying a woman’s confidence. Whether he was referring to his spouse or a theoretical party with whom he might become involved, however, Washington never made clear.

By upbringing, experience, and nature, Eliza Powel was politically astute and acquainted with the leading lights of the American political scene. It was in reply to her question about what type of government the Constitutional Convention had chosen that Benjamin Franklin directed his famous remark, “A republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

Perhaps because Washington left few written records of his meetings with her, the Powel/Washington relationship intrigues historians. Chernow notes in A Life that the bond between Eliza and George was Washington’s “only deep one with a woman who qualified as an intellectual peer and treated him as such.” Powel could banter and even flirt with Washington, but she also held him on a pedestal, sometimes comparing him to great men of antiquity.

Eliza Powel was far more sophisticated and worldly than Martha Washington, who acknowledged that compared to Eliza she was naïve and clumsy. Yet Martha appeared

not to resent her husband’s close friendship with Powel. In fact, Martha often turned to Eliza, who had lost three children, for advice about raising her three granddaughters.

From 1774 to 1787, there is no record of any contact or correspondence between George and Eliza. In 1790, with independence achieved and the business of creating a government under way, Congress picked Philadelphia as a temporary capital, drawing Washington back to his female friend’s hometown. Again installed in Philadelphia, Washington frequently escorted Eliza on carriage rides and had tea with her at her home—in husband Samuel’s absence. Even though both were in the same city, the two often exchanged letters. These were, for the most part, brief notes in which Washington informed Powel when she would be picked up to visit a particular person or attend a play or to thank her for bringing his attention to a pamphlet she thought he ought to read. The letters’ salutations and closings became increasingly more personal and affectionate, even given the context of the time, with its florid hellos and goodbyes. Effusiveness was unusual for the austere Washington, whose epistolary persona was formal and cold. In a letter from Eliza to Washington she sends him a small gift and signs off, “I am with great Sincerity, dear Sir, Your affectionate friend. . .” In a letter to Eliza, George thanks her for sending a copy of a pamphlet and closes, “with very great esteem, regard and Affection. . .”

According to Chernow, only Washington’s youthful love for Sally Fairfax surpassed the affection he developed for Eliza Powel.

Early in November 1792, Washington was in the third year of his first term as president. Consensus held that he should remain at the nation’s helm for another term to get the young country onto solid footing. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, who disagreed about virtually everything else, both wanted Washington to continue as president. However, the man himself was not only uncertain about seeking a second term but was thinking of resigning his office early—a musing that George mentioned to his friend Eliza.

On November 17, Powel sat at her writing desk and in a seven-page letter reminded her friend the president of his responsibilities to the millions who looked to him to guide the ship of state. Resigning would cost him his popularity, she said. Resignation would please his enemies and cause his friends and followers dismay and regret. Some would question his motives or call him self-serving. “The Antifederalists would use it as an argument for dissolving the Union” and claim that Washington, finding the system flawed, was absconding lest blame for its failure fall on his shoulders, Eliza declared. Finally, Powel invoked the prosperity and happiness of the people that the nation had entrusted to him, closing with “Your sincere affectionate Friend.” Chernow maintains that Eliza’s letter was among factors that bucked George up. He stayed on the job and did run again in 1793—as in his first campaign, taking every electoral vote.

The summer of 1793 saw yellow fever sweep Philadelphia. The epidemic killed 5,000—a tenth of the capital’s population. At first, Washington dismissed the threat but changed his mind, deciding that he and his family had best depart for Mount Vernon. He suggested to Eliza that she and Samuel accompany them, but Samuel Powel wanted to remain in Philadelphia. Eliza too stayed, telling George that if she left her husband on his own she would never forgive herself. The Washingtons departed. Samuel Powel contracted yellow fever. Eliza nursed him but, three weeks after the general’s invitation, while she was visiting her brother on his farm, her husband died. When Washington returned from his plantation, his friendship with the widow Powel tightened.

After Americans elected John Adams president in 1797, Washington cleared out his official residence in Philadelphia. In the process of disposing of many furnishings he had bought for the house, he sold Eliza his private desk at cost. Examining the desk later, she found in a secret compartment a packet of letters from Martha to George. Eliza wrote Washington a teasing tongue-in-cheek letter revealing her discovery, assuring her friend that though she assumed the missives were love letters she had not peeked but instead had triple-sealed them against prying eyes. Washington answered with thanks, explaining that in her letters to him Martha had expressed friendship rather than romantic love. Anyone expecting to find evidence of “carnal desire or lusty romance” would be sorely disappointed, George said.

In her final letter to George Washington, written in December 1798, Eliza Powel expressed hope that the Almighty would protect and preserve the former president. She signed off, “with deepest Admiration and Affection.” Washington responded briefly and formally, showing none of the warmth of previous letters to her, perhaps a tacit message that this was the end of their special relationship.

After undertaking a rainy, snow-blown five-hour tour of his plantation on December 12, 1799, Washington, soaked to the skin, joined guests waiting for a meal. On December 14, he died of a bacterial infection, followed to the grave in May 1802 by Martha.

Eliza Willing Powel never remarried. There is no record that she wrote a letter of condolence to Martha Washington after her great friend’s death, nor any evidence that her friendship with Washington, close though it was, exceeded the boundaries of propriety. Eliza Powel died in 1830.

Washington danced here

Philadelphia’s Society Hill section, abutting popular historic sites like Independence Hall, throngs with tourists, many of whom walk unknowing past 244 South Third Street. That address is one of the finest examples in the city of Georgian residential architecture, as well as the setting before and after colonial times for sumptuous gatherings of the wealthy and powerful.

In 1760 William Penn’s sons, Thomas and Richard, sold the parcel at 244 Third to dry goods merchant Charles Stedman. Finishing construction in 1766, Stedman, now in dire financial straits, put the property up for sale. He unloaded it on August 2, 1769, for £3,150 to Samuel Powel. Five days later, Powel wed Elizabeth Willing.

Both spouses came from clout. Samuel had inherited his merchant father’s fortune at nine and another at 18 from his grandfather, positioning him for nonpareil access to education, acculturation, travel, and connections. Eliza was of clans Shippen and Willing, names synonymous in 18th- century Philadelphia with public service and wealth; her great-grandfather, father, and brother served as mayor.

The Powels became a power couple, their aura enhanced by a lavish 1769-71 refurbishing of their home. The renovation included work by woodworker and gilder Hercules Courtney, whom the Powels paid £60 for decorative carving at a time when £200 built a small brick house; the efforts of decorative plasterer James Clow; and painting and bordering by Timothy Berrett.

From mahogany doors and central stairs to an ornate mantel illustrating Aesop’s fable “The Dog and his Reflection,” the Powels spared no detail telegraphing their standing, which came to include Samuel’s service as mayor 1775-76 and Eliza’s reputation as an intellectual.

The Marquis de Chastellux, after visiting Philadelphia in 1780, wrote in Travels in North America that “contrary to American custom, [Mrs. Powel] plays the leading role in the family—la prima figura, as the Italians say…she has not traveled, but she has wit and a good memory, speaks well and talks a great deal; she honored me with her friendship and found me very meritorious because I meritoriously listened to her.”

The pair’s energetic hospitality made 244 South Third a locus of American social and political life in which the powerful and well-connected could mingle, dine, influence, drink, be influenced, and dance. John Adams, in Philadelphia for the First Continental Congress, wrote in his diary on September 8, 1774: “Dined at Mr. Powells…A most sinfull Feast again! Every Thing which could delight the Eye, or allure the Taste, Curds and Creams, Jellies, Sweet meats of various sorts, 20 sorts of Tarts, fools, Trifles, floating Islands, whippd Sillabubs &c. &c.Parmesan Cheese, Punch, Wine, Porter, Beer &c. &c…. At Evening We climbed up the Steeple of Christ Church, with Mr. Reed, from whence We had a clear and full View of the whole City and of Delaware River.”

The Powels’ guest lists included the Marquis de Lafayette, Benjamin Franklin—and George and Martha Washington, who formed a close relationship with the younger couple that included the exchange of hospitality and gifts. The Powels visited Mount Vernon and the Washingtons celebrated their wedding anniversary at the Powels’ home.

In 1779 Sarah Franklin Bache wrote to her father, Benjamin Franklin: “I have lately and several times invited abroad with the General and Mrs. Washington, he always inquires after you in the most affectionate Manner and speaks of you highly. We danced at Mr. Powel’s your birthday Eve night I should say in Company together and he told me it was the anniversary of his marriage it was twenty years that night.”

Eliza’s 50th birthday celebration in February 1793 so impressed one guest that in 1830, more than three decades later, he noted in his diary that Eliza had died—and reminisced about her party.

Eliza lived in the house for five years after Samuel’s death, eventually selling 244 South Third to neighbor William Bingham. Powel House’s final private owner, Wolf Klebansky, was using the house commercially when, in the 1920s, he decided to flatten it to put in a parking lot. In its first undertaking, the newly formed Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks saved 244 South Third in 1931, but not before Klebansky sold the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York key architectural elements from two second-floor rooms, recreated in those institutions’ permanent collections.

Renovated and refurnished, Powel House—philalandmarks.org/powel-house—is open to the public. Entering, the visitor encounters a spacious foyer leading to the main staircase. Beneath 12-foot ceilings, an arch frames the stairs. Excellent examples of period furnishings create an elegant, amiable impression, as though Samuel and Eliza were waiting to welcome guests.

—Kevin J. Lawrence, a Philadelphia writer, lives a few blocks from the Powel House.