Two letters by North Carolina soldiers describe the Battle of Gettysburg

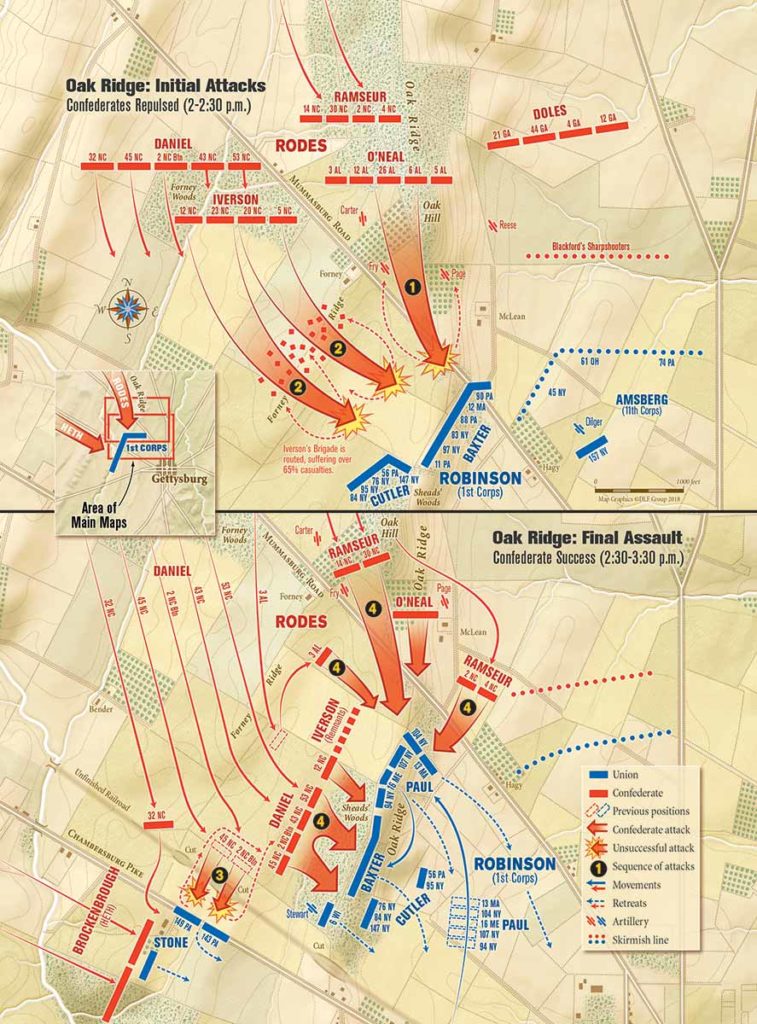

By the time Confederate Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur’s North Carolina brigade of Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ Division arrived at Gettysburg’s Oak Hill on the afternoon of July 1, 1863, the fields and woodlots in the vicinity were already littered with the dead and dying men of Brig. Gens. Alfred Iverson’s and Edward O’Neal’s brigades, also of Rodes’ Division. After a brief rest, Ramseur received orders to divide his brigade and send the 2nd and 4th North Carolina regiments under Colonel Bryan Grimes east and then south down Oak Ridge to attack the far right flank of the Union 1st Corps line.

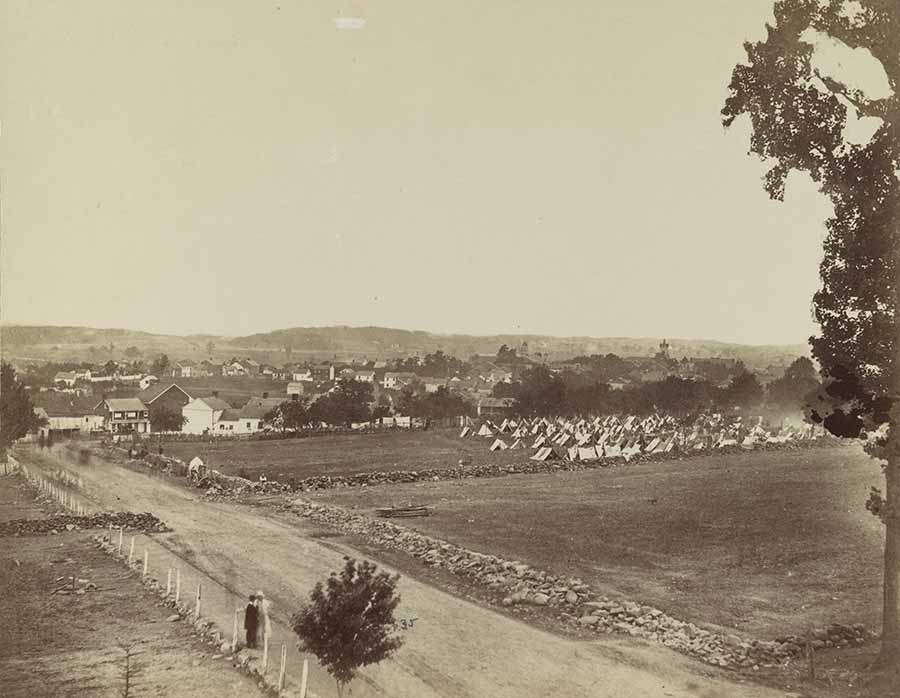

Despite a “severe, galling and enfilading fire” poured into Grimes’ regiments as they moved off Oak Hill, the prominence at the end of Oak Ridge, the North Carolinians assisted in outflanking an enemy brigade and driving the Federals back into the streets of Gettysburg. The two accounts provided here from the 2nd North Carolina Infantry include vivid descriptions of that fighting. Compared to the other brigades in Rodes’ Division, Ramseur’s regiments sustained few casualties at Gettysburg, the 2nd lost only four dead and 27 wounded.

The editor of the The Raleigh Standard did not name the officer of the 2nd North Carolina whose letter, which recounts the entire three days of the battle, is the first one presented here, but the Thomas Gorman Papers at the North Carolina State Archives identify the author as Captain John Calvin Gorman (1835-1893). Gorman had been a printer and journalist in Kansas and North Carolina before enlisting as a lieutenant in Company B of the 2nd in May 1861. Gorman suffered wounds at Antietam and Fredericksburg, while also being promoted to captain. Following the Gettysburg Campaign, Captain Gorman served with the 2nd until his capture during the Battle of Harris’ Farm on May 19, 1864, near Spotsylvania Court House. Gorman was initially one of 600 captive Confederate officers transported from Fort Delaware to the vicinity of Charleston in September 1864, but illness resulted in him being separated from the “Immortal Six Hundred” and sent to a hospital in Beaufort, S.C. After being exchanged in December 1864, Gorman returned home for several months before rejoining his regiment in early March 1865. He recounted his experiences in the Appomattox Campaign in a small book published in Raleigh in 1866, titled Lee’s Last Campaign.

Ordnance Sergeant Alexander Murdock of the 2nd wrote the last letter, which discusses only the fighting on July 1 and which echoes Gorman’s disappointment and longing for the leadership of Stonewall Jackson. Murdock enlisted at age 30 in the 2nd’s Company H in May 1861, and was promoted to ordnance sergeant a year later. He appears as present on all regimental muster rolls until the time of his death in a Staunton, Va., hospital on July 1, 1864. Excerpts from Murdock’s letter appear courtesy of Cal Packard, MuseumQualityAmericana.com

August 4, 1863

Semi-Weekly Standard (Raleigh, N.C.)

Battles of Gettysburg

We have been permitted to make the following interesting extracts from a letter written by a gallant young officer of the 2d N.C. regiment, Ramseur’s brigade, to his mother in this City:

Just as we arrived on the ground, our division was recovering from a repulse, in which Iverson’s N.C. brigade, and Daniel’s N.C. brigade were badly cut up. Things looked decidedly blue, but lines were reformed, and again we advanced, our brigade being assigned a position on the left that overlooked the enemy. The right and centre were soon engaged, and brought to a halt, but amid bursting shells and whistling bullets we steadily advanced, until we had driven the enemy’s weak right beyond their main line, when our gallant Brigadier, Ramseur, seeing the advantage, in the face of a torrent of bullets, wheeled his entire brigade to the right, and before the Yankees could think, we were pouring showers of rifle balls into their right flank and rear. Their whole line broke and fled, and at one time I was fearful their running troops would crush our little brigade. We had them fairly in a pen, with only one gap open—the turnpike that led into Gettysburg—and hither they fled 20 deep, we all the while popping it to them as fast [as] we could load and fire, and into town we rushed pell-mell after them, our brigade in the advance. I was with my company in the skirmish line, in front, and when the Yankees got into town they hid by hundreds in houses and barns, and I had the felicity of capturing any number. I got three swords and two pistols from officers who surrendered to me. We captured 7,600 prisoners during the fight, while the enemy left the fields covered with the dead and wounded.

Just at the close of the fight, the other divisions of our corps came up, but they had hardly a chance to fire a gun. Our division had borne the brunt of the fight, by itself. We lost 3,000 men killed, wounded and missing out of about 10,000. Our brigade loss was comparatively slight, and I had only one man wounded. The enemy had fled south of the town, and had taken position on the ridge that caused us all our after loss. Instead of following the enemy up, and continuing the fight, (as “old Jack” would have done,) the pursuit was carried no further than the base of the enemy’s new position, when our line were halted for the day, and new lines of battle were formed, and we rested in that position till the next day, waiting for Longstreet and Hill to come up. That delay was fatal to us. Our new line of battle extended through the streets of Gettysburg, and there we slept that night. It is the opinion of many that we lost the golden opportunity in not keeping up the attack that evening, and I concur in that opinion. The evening’s reinforcement had not come up; they had been badly whipped and demoralized, and it is believed that we could have taken their position that evening with the loss of less than 500. It afterwards cost us 10,000 and then we could not hold it. Had we taken it that evening it is hardly possible to say, how great our victory would have been. Washington would have been evacuated, Baltimore would have been free, Maryland unfettered, the enemy discomfitted, and our victorious banners flaunting defiantly before the panic-stricken North. There we missed the genius of [T.J. “Stonewall”] Jackson. The simplest soldier in the ranks felt it, and results have proven it. But, timidity in the commander that stepped into the shoes of the fearless Jackson, prompted delay, and all night long the busy axes from tens of thousands of busy hands on that crest, rang out clearly on the night air, and bespoke the preparation the enemy were making for the morrow, while our troops were feasting on the good things the fleeing inhabitants of Gettysburg had left in their open and deserted houses, and the sun of the 2d of July rose on a pillaged city, and a feasted army, on our side, while embrazured eminences and frowning cannon arose from the forest, as if by magic, in our front. The enemy’s whole army had come up during the night, and so had ours. They occupied a crest or ridge, mountain like in appearance, running 3 miles north east by south west from Gettysburg, while our troops were deployed some half mile from its base, fronting them, Longstreet on the right, Hill in the centre, and Ewell on the left, while our artillery was placed on an elevated ridge behind the infantry line. Skirmishing rattled along the line from daylight to dark, but until 3 p.m. of the 2d, no heavy fighting took place, the time being occupied in making dispositions and preparing for the onslaught. The position of our division was immediately to the right of the town, where the enemy’s position was the steepest, and where there was less likelihood of making a successful attack, and Gen. Lee intended us only to hold our position, while those troops on the right and left of us, charged the enemy. On the extreme right, Lee made his utmost endeavors to drive the enemy, and there the hardest fighting took place. The other positions were only assailed in order that the enemy might not know where to mass his greatest force.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The roar of artillery was incessant[/quote]

At 3 P.M. the ball opened. For two hours the roar of artillery was incessant, and the howling and screeching of two hundred shells minutely shot over our heads. Frank Ramsay was killed during this artillery duel while loading his gun, a piece of shell passing diagonally through his lungs. I learn that his last words were, “Tell my wife I died at my post like a man.” I saw a testament he carried in his pocket; it was saturated with his heart’s blood. He was the only man killed in his battery. At 5 o’clock, the roar of artillery died on the ear, and our eager lines to the right and left of us advanced under a dense canopy of sulphurous smoke that densely hung in lowering clouds at the base of the enemy’s position. I watched their long lines as they advanced with flying colors, and none but a patriot can realize the emotion that filled my breast, and the thoughts that flitted through my mind. It was a time when hours were compressed into minutes, hearts cease throbbing, and the blood lies dormant in your veins. They are finally hid from view, and then began the terrible rattle of musketry, sounding not unlike the pelting of hail on the housetop, until it finally culminates in a continuous roar that language cannot describe, while the detonating thunder of artillery again sets in and adds new horrors to the bloody drama of death that is going on. Sometimes the ear can catch the pealing cheer of our men ringing out amid the din as some advantage is gained, and our hearts beat tumultuously with joy, only to be again oppressed by hearing the hated “huzzah” of the enemy. Thus the fight continues until long after the sun has set, until, perhaps 10 o’clock, when it gradually ceases, and an oppressive silence reigned until daylight, only disturbed by the distant groaning of the wounded and dying that cover the ground. Thus ended the second days fight.

We lay and slept in line of battle in our old position in dread uncertainty as to the result of the day’s fight. At dawn we learned that Longstreet’s corps had crossed the enemy’s position on the right, but on account of overpowering odds the enemy had hurled against him, he was forced to fall back, leaving all but four of the 15 pieces of artillery he had captured. Hill’s forces also drove the enemy from the centre, but he, too, was forced back while the divisions on our left were equally unfortunate. In fact, the hard fighting of our troops was barren of results.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]I thought our leaders must be mad[/quote]

July 3. The day wore on, and an anxious silence reigned. Only the pickets kept up a desultory firing. The hour of battle—3 o’clock—again came, and from the stir amongst the artillery in our rear, I knew that one more effort would be made. We had one hundred and fifty pieces of artillery in position, while, perhaps the enemy had 200. We began the fight, and the oldest soldier in our army says he never witnessed anything that equaled it. The lumbering of the thunder overhead, (as a squall passed during the fight,) was but as the wail of an infant to the roar of a lion, in comparison with the deafening roar that shook the ground. It lasted for three long hours, and the last hour the rattle of musketry commingled with the fierce roar of the artillery. The same scene was enacted as of the day before, with the like results, as we could tell by the loud “huzzah” of the enemy that rang in my ears with the painfulness of the expressed anguish of a mother weeping at the death of her first born. Once more we were forced to leave works that the most daring courage and heroism was evinced to take. Just at night, we (I mean our division,) was ordered to make a night attack on the position in front of us as a forlorn hope. We were to attack with the bayonet alone, our brigade in advance, with Daniel as support. Our battle cry was to be, “North-Carolina to the rescue!” The attack was to be made just as the moon arose. In front of us, hid only by a slight hill, stood this frowning eminence, cleared of timber, and crowned with artillery thickly parked. Between its base and summit, two long lines of stone fence ran parallel with the summit, and behind these rock walls two lines of battle stood, musket and rifle in hand awaiting our approach. The order astounded me, and I thought surely our leaders must be mad, or ignorant of the position, or else they think our little brigade of 900 can accomplish impossibilities. But the hour of trial approaches. In his characteristically clear, ringing voice, our noble commander gives the word, “Forward!” We spring forward and clutch our arms nervously; I gave in faces I never expect to see again on earth. Pocket books and last messages are hurriedly given to Surgeons, and those whose duties cause them to remain in the rear, and we march boldly forward, sweeping in good line through the tall wheat that divides our position. We near the base of the hill that towers and looms up, mountain like, in our immediate front, and halt at a low given command within the pale of a graveyard with marble monuments that seem typical of our fate. The enemy seem aware of our approach. Their commands can be heard, and they are evidently preparing to receive us. We are ordered to lie down, and our great hearts thump and beat within our bosoms as if they would leap out, while noble Ramseur and scouts creep forward to reconnoitre. For 10 minutes we lay in dire suspense. A few random shots are fired, and a few whistling shells from artillery whistle over our heads, and we expect the whole air to blaze forth with leaden and iron hail. But the firing ceases and silence reigns. The rising moon creeps under a cloud. Messengers are sent down our lines, and instead of the dismal death-knell sound of “forward,” the gladly obeyed command of “fall back without noise” is given, and soon we are again back in our old places in line of battle. Our General saw the fool-hardiness and madness of the attempt, and being unwilling knowingly to sacrifice his command, he on his own responsibility, ordered us back; and for that act there are many Carolina mothers, wives, sisters and children who should pray blessings on his head. Thus ended the battle of the 3d of July. The losses on our part in the three days fight was heavy—15 or 20,000, doubtless. The enemy’s are probably much heavier.”

August 10, 1863

Camp near Orange Court House

My Dear Brother,

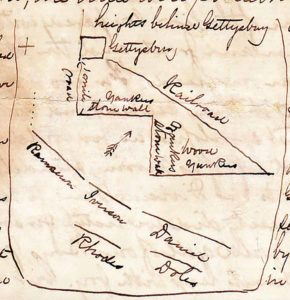

…The Battle of Gettysburg was badly conducted. In the first place our Division was almost marched at a double quick for 7 miles. Iversons N.C. Brigade being in front then came Daniels N.C. Brigade, then Doles Georgia Brigade then Rhodes’ old brigade of Alabamians, and last our small but veteran Brigade Commanded by our beloved Gen. Ramseur, composed of the 2nd 4th 14th & 30th N.C. Regts. We stopped for about three minutes on the roadside, about a mile from where we knew the Yankees were. As we advanced to our position in line of battle (each Brigade engaging the enemy as they came up in the order above enumerated) we were astounded to get the news from stragglers and skulkers that our Division was driven back with heavy loss. Our Brave Boys laughed and said that they were not driven back and were not likely to be. It was only a few minutes until we could hear the whistling of the bullets was heard over our heads and ever and anon one would strike in our ranks. Here we were ordered to lie down and wait until the Gen. came back when away rode our Brave Ramseur to reconoiter the ground. Here then Brother is the time when we feel the need of a sustaining Saviour and a firm reliance on the promises in God’s holy word. I have seen the most abandoned sinner’s cheek blanch, his lips quiver, and his eye raised to heaven as if seeking assistance from that God whom he had scoffed and scorned in such an hour as this. Many a heartfelt and earnest prayer then ascends to Heaven from lips that at other times never utter one. And here I have felt impressions on my heart that I pray to God may never never be erased. There we lay looking around upon our comrades and wondering who would be the ones who would be taken from us and in full health with the life blood coursing joyously through our veins we stared death in the face. The loved ones at home were not forgotten at this moment, but every well beloved face and every name remembered. Whilst ever and anon you could hear “If I am killed and you come out safe carry such a message home and take this memento.” Sooner than it has taken me to write this, the Gen. rides back and gives the command “forward,” the lines were something like this (diagram above).

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Bullets was heard over our heads[/quote]

Iverson’s Brigade marched right up in the direction I have made the arrow, and of course got a flank fire from both stone walls and one right in front. Iverson was nowhere to be found on the battlefield. It is said that he took his position behind a tree about ½ mile from it, of this I cannot say such is the report. When we came up Gen Ramseur sent two Regts. by the left flank in the direction of the dotted line and by this means flanked the Yankees and in ten minutes we had them running in full retreat on Gettysburg. Johnstons division came up on our left, where I have made the cross. By the time we got into Gettysburg, it was about 6 oclock, and here was when the failure was made (and if Jackson had been with us it would not have been done.) We ought to have marched right [onto?] the heights that night and we would have taken them; but we laid quietly down in the streets of Gettysburg and feasted on many a good thing: preserves of all kinds, and the finest sort of bread taken from those houses which were deserted. That night the Yankees wrought hard all night fortifying the heights and the next day the whole of the Yankee army came up as well as ours….Yours fraternally, Sandie

Keith Bohannon is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, Ga. He has an essay on the destruction of Confederate Army records during the Appomattox Campaign in Petersburg to Appomattox: The End of the War in Virginia (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), edited by Caroline Janney.