In 1914 Caspar René Gregory, an internationally known biblical scholar, decided to go to war for his adopted homeland.

On August 11, 1914, His Majesty’s Regular Army took out a full-page advertisement in the London Daily Telegraph seeking the immediate enlistment of an additional 100,000 men, ages 19 to 30, to help with the “grave National Emergency” unfolding beyond the borders of Great Britain.

Nine days earlier, Europe had begun fraying at its seams. Germany invaded Luxembourg and then Belgium after the Belgian government denied German forces passage across their nation for a planned assault on Paris. The British government pledged its military support to the historically neutral Belgium, and the budding Great War went into overdrive. In Liège, for example, some 30 miles southwest of the German border, the American war correspondent Granville Roland Fortescue—a Rough Rider who had been wounded in Cuba fighting alongside cousin Teddy Roosevelt in the Battle of San Juan Hill—witnessed the precision with which invading troops bombarded a trio of strongholds, leading to the capture of the Belgian city. “The artillery practice was perfect,” he wrote in an eyewitness scoop. “Shell after shell was exploded fairly on the ramparts of the forts.” Shortly thereafter, a German counter-attack at the Battle of Mulhouse, 300 miles to the south, wrested from the French this sliver of Alsace its troops had briefly occupied.

With hostilities escalating, British men of fighting age heeded the urgent call for service by Lord Horatio Kitchener, a colonial administrator and veteran of military campaigns who had reluctantly accepted the position of secretary of state for war. In one weekend alone, about 6,000 recruits—many of them with previous military service—answered the call to arms.

Meanwhile, Germany’s elaborate conscription system was providing its military with an enormous pool of draft-age men to call on. In August alone the army had expanded its fighting forces from 808,000 to more than 3.5 million in less than two weeks.

Among that massive contingent was an American émigré who volunteered on the very day that Fortescue’s dispatch from Liège and Lord Kitchener’s full-page ad—capped with an emphatic Edwardian-style God Save the King—graced Britain’s newspaper of record. Caspar René Gregory, an American expatriate, high-profile social reformer, and internationally known biblical scholar enlisted as a private in the 1st Reserve-Battalion of Infanterie-Regiment “König Georg” No. 106 of the Imperial German Army’s 24th Division. By any measure, Gregory was an unlikely enlistee. But one characteristic in particular gave him exalted status in his adopted homeland: At nearly 68 years old, he was the oldest volunteer in Kaiser Wilhelm II’s forces.

Caspar René Gregory, born of Gallic extraction, was a descendant of Abbé Henri Grégoire, a prominent leader of the French Revolution who championed such causes as abolition of slavery and universal suffrage. Gregory’s grandfather followed the Marquis de Lafayette to North America, anglicized the family name, and fought in the Revolutionary War. His son, in turn, founded a private school in his hometown of Philadelphia, which Caspar Gregory attended until he enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania. By all accounts a brilliant student, he went on to study at Princeton Theological Seminary. But what most impressed Gregory’s friends was his strong sense of purpose and commitment to civic duty, much in keeping with his patriotic heritage.

Gregory was a student at Penn during the American Civil War, and he was an active participant in the military training provided there. Assigned to the ordnance corps, he later volunteered for the First Regiment of Pennsylvania Gray Reserves.

After graduation Gregory went abroad to pursue a new form of biblical studies called textual criticism, which had been pioneered by Professor Constantin von Tischendorf at the University of Leipzig. Tischendorf died a year after his arrival, but Gregory showed such talent and promise that the university asked him to continue his mentor’s work.

Gregory finished his doctoral studies in 1884, was admitted to the faculty, and became a full professor in 1891. Over that time, he made an important discovery that helped scholars evaluate biblical manuscripts: He determined that ancient scribes arranged their parchment leaves so that the grainy sides of the pages faced grainy sides, while smooth sides also faced one another. That simple discovery—dubbed Gregory’s Law—gave textual scholars a valuable new method to evaluate manuscripts. Gregory became so respected in the world of New Testament studies that he later participated in high-level discussions to determine which books should appear in the Biblical canon.

The longer Gregory lived in Leipzig and worked at the university, the more he came to admire German culture. He became a naturalized citizen of Saxony in 1881, and thereafter returned to his native land infrequently and briefly. To enrich his teaching, Gregory traveled incessantly, especially around the Mediterranean Sea, during summer breaks. After studying in Athens, Cairo, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, he expanded his scholarly journeys to include St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kiev, and Moscow, invariably finding his way to each city’s preeminent theological library.

But his base remained Leipzig, and when the autumn term rolled around, he could always be found at the lectern and in the streets and halls of the industrial city. His acquaintances came to believe that he was determined to become “more German than the Germans,” although he embraced the life of his adopted land with a notable twist: He infused a firm commitment to Christian charity into traditional German efficiency. As a result, he greeted everyone on his walks through Leipzig and distributed money to the needy, even paying tuition for a student no longer able to afford it. His kindnesses were so many that he became known as a “national treasure of Saxony.” Or as the Germans put it, “a property of the people.”

Gregory’s commitment to the fatherland and strong sense of duty made his decision to volunteer for military service a principled one, despite his looming 68th birthday. He said he believed that Germany had been forced into war against “English imperialism, Frenchmen, and Russian [Cz]arism.” And then there was the solidarity he felt with his fellow citizens. “I could not let them go alone [into the army], could I?” he said. “It was my social duty to join. I joined to help my neighbor who was now my comrade.”

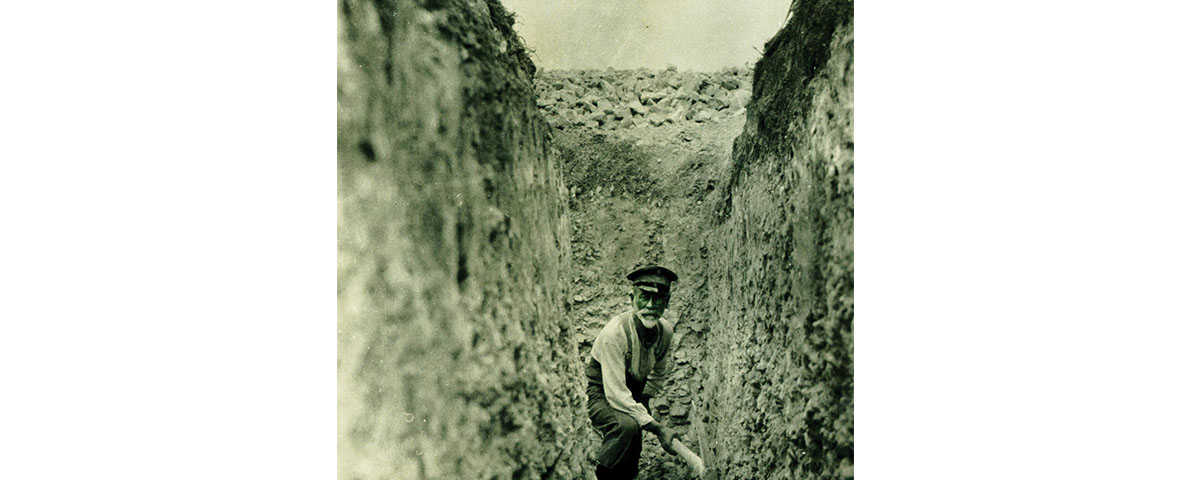

Gregory firmly believed in Kaiser Wilhelm’s optimistic promise that the troops would return home before “the leaves fell from the trees,” so on that second Tuesday in August of 1914, the physically fit, sweet-faced sexagenarian offered himself for service. And true to his concept of duty, Gregory did not seek the protection of rear areas, but reportedly soldiered in the front lines at Dinant on the Meuse, the Somme, Lille, Flanders, and eventually the muddy hell of Ypres. In each of his assignments, in fact, the physically fit scholar professed an “urgent desire to be deployed in the trenches.”

Gregory was soon promoted to sergeant, and he became famous across Germany. On the battlefield, where his brethren always kept close tabs on his well–being, his tasks included supervising the construction and maintenance of military cemeteries. Gregory’s commanders seemed to particularly value both his wisdom and his inspirational influence on younger soldiers, whom he treated with his customary kindness and understanding. He was held in such high regard, in fact, that the entire nation celebrated his 70th birthday to honor him as an exemplar of service. To mark the occasion, the kaiser awarded him the Iron Cross Second Class, while the Kingdom of Saxony presented him the Friedrich August Medal in Silver, awarded for meritorious army service.

By 1916 Gregory’s adopted nation was beginning to suffer from a depleted economy at home and exhaustion at the front, and it would not be long before American doughboys began arriving in large numbers.

In October Gregory was reassigned to the 47th Landwehr Division in northeast France, where he immediately pressed superiors for a post at the front. His captain offered him a choice: return to the trenches at his rank of staff sergeant, or be promoted to lieutenant in recognition of his service to the fatherland. “I don’t care for a promotion,” Gregory replied. “It is to me the job that counts, and I will return to the trenches.” Ultimately, the captain dismissed Gregory’s wishes by promoting him, 10 days after his 70th birthday, to lead Kommando Gregory, a unit charged with the registration of graves and military burials. The assignment was clearly designed to keep him out of harm’s way, but thanks to the inscrutable logic of the battlefield, it actually led to his demise.

Although some reports contend that the aging lieutenant was felled in battle leading his troops, more-credible accounts suggest that while supervising grave digging behind the front lines, Gregory’s horse, Nina, was killed in a French bombardment and fell on him, badly injuring his left knee. Gregory was taken to the field headquarters near Neufchâtel–sur-Aisne, but unable to move from his bed during a subsequent Allied artillery barrage, he was struck by shrapnel. “Lift my stuff carefully,” he reportedly told an attendant before losing consciousness. He died one day later.

Nearly three years earlier, the noted theologian had penned the two-paragraph death notice that was to eventually appear with the proper date inserted: “Caspar René Gregory, professor at Leipzig University, fell in battle for the German cause April 9, 1917. His family must not wear mourning or lament his loss, but should be happy that he is resting in God. Visits of condolence ought to be omitted. He extends a hearty farewell and a hopeful ‘auf wiedersehen’ to all his friends and acquaintances.”

The city of Leipzig erected a memorial to Gregory near his home, which stands today. But the most poignant memorials no doubt came from his American friends, who grieved their loss profoundly, even as they admitted puzzlement at his choice to serve a ruler they perceived as a dictator and a nation they believed was an aggressor. An old friend from his college days wrote, “At least our American-German Gregory, of Leipzig, took refuge behind neither age nor class nor scruple, but threw himself with all the boyish energy we remember so well into a course he believed in, though we think it false and lost, and so tragically died in the land of his forefathers, but with the army of its foes.” MHQ

William Walker lives in Staunton, Virginia. He is the author of Betrayal at Little Gibraltar: A German Fortress, a Treacherous American General, and the Battle to End World War I (Scribner, 2016).