Amid the confusing chaos and searing carnage of war, twists of fate often seem to be the main determinant of who lives and who dies. For those who survive, luck may certainly play an outsize role. But wily resourcefulness can be equally crucial. In the bloody kill zone of Budapest, Hungary, during the waning months of World War II in Europe, Ferenc “Feri” Shatz was fortunate to have plenty of both. And he would need it to emerge unscathed from multiple brushes with death, sometimes by a razor-thin margin.

Shatz’s path to survival began in October 1944, in a cornfield on the outskirts of the Hungarian capital. The short, slight, 18-year-old Jew had endured months of brutal service rebuilding bombed-out railroads and highways as a slave laborer in a Nazi forced-work battalion and felt certain he could not endure the grueling 15-hour workdays much longer. The guards murdered any workers who fell injured or exhausted, so Shatz knew that if he faltered, his reward would be a bullet to the head.

The teen had devised a desperate, daring plan, and the chance to employ it arrived suddenly one day as he and his fellow Jewish workers struggled to repair damaged rail lines just north of the Hungarian capital. “It was American bombers that provided my means of escape,” Frank (anglicized from Ferenc) Shatz recalls today. “They had begun to bomb the railroads and roads that carried troops and supplies to the Eastern Front. Budapest was high on the target list, because it was a transportation hub.”

As Allied ordnance fell, the Nazi guards ordered the laborers to disperse into a nearby cornfield and hide in the stalks. Shatz shivered as the huge bombs exploded, but he had experienced such air raids before, and in fact was ready for this one. For days, beneath his tattered prisoner’s uniform, Shatz had worn civilian clothes given to him a few weeks earlier as protection against the cold by a couple he had met in a small town east of Budapest. The garments would be instrumental to his escape.

As Shatz lay in the cornfield, he shed his prisoner’s uniform and slowly began to crawl away from the rail line. He had covered several hundred yards when the all-clear signal sounded and his comrades were ordered back to work, but Shatz knew the group was large enough that he would not be missed until that evening’s roll call at the earliest.

After creeping on all fours through the cornfield for what seemed like hours, he reached a road and began to walk toward the nearest tram line into Budapest. As a teenager from a well-to-do family in a town just across the border in Czechoslovakia, Shatz had visited the city often, enjoying its vibrant cafes, bars, restaurants, and music halls with other prosperous, well-educated young Jews.

This was not the same city. The Nazis had taken over Budapest, and Adolf Eichmann was working furiously to deport as many Jews as possible to Auschwitz before the war ended. Making matters worse, a group of indigenous fascists known as the Nyilaskeresztes Párt (Arrow Cross Party) later deposed the government of Hungarian leader Miklos Horthy, and gangs of its leather-clad thugs roamed the city’s streets, torturing and killing any Jews who had managed to evade Eichmann’s trains to the Nazi death camp located in Poland.

Simultaneously, Soviet Red Army forces advancing east were encircling Budapest. With anti-Semitic hatred boiling within the city and Soviet troops beginning to besiege it from without, a pall of impending doom hovered over the Jews huddled in makeshift ghettos and private homes.

Shatz headed toward this fiery cauldron on a crowded tram, which passengers could board without a ticket if they eluded the transit police, who performed occasional spot checks. As Shatz neared the Danube River, he jumped off the tram, strode toward the city center, and had another astonishing bit of good luck when he spotted his brother-in-law Béla walking directly toward him.

“Feri, what are you doing here?” Béla gasped in amazement. After Shatz related his harrowing tale, Béla told of his own escape from a forced labor camp at a copper mine in Serbia. Both men were familiar with Budapest, having visited it often in the past. Now they had come to the city with the same goal in mind: to find shelter in its large Jewish community amid the extensive administrative confusion sparked by the considerable friction between the Nazis, the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian army, and the deposed Hungarian government.

Béla had joined the Maccabi Hatzair, an organization that had promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine before the war. After the Nazis shut down its immigration program, the group had gone underground and developed ties to diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, Sweden’s special envoy to Budapest, who was surreptitiously working to save the city’s Jews. The young men and women of the Hatzair delivered identity papers and diplomatic protection documents to Jews in the city and moved supplies among safehouses, dangerous tasks that exposed them to the roving Arrow Cross gangs.

Béla took Shatz to a safehouse near St. Stephen’s Basilica, in the heart of Budapest, where he could temporarily eat and sleep. This was one of a number of such places that Wallenberg had set up around the city under the nominal protection of the Swedish government.

In 1944, during the Red Army’s siege of the city, the Soviets captured Wallenberg, and he was never again seen alive. “Wallenberg saved thousands of Jews, prying them out from the jaws of death,” Shatz says. “The unquestionably heroic deeds he performed have remained an inspiration to me throughout my life.”

Shatz promptly agreed to join the Hatzair, and Béla taught him how to stay relatively safe while carrying out the group’s dangerous missions around the city. Shatz memorized the location of Arrow Cross checkpoints and learned how to use subways and trams to avoid the gangs, knowing that if he was caught, he would be executed.

As part of his duties, Shatz was assigned to assist Rezső Kasztner, a Jewish lawyer negotiating with German officials to secure the release of Jews to neutral Switzerland. The apparent benevolence of the Nazis was in fact self–serving. Many senior German officials who had relocated to Budapest ahead of Allied forces advancing from the west now knew their cause was lost and had begun reaching out to Allied representatives, seeking money or gold to fund their own escapes or hoping to build ties to people who might offer safety from Allied justice after the war.

Because Kasztner worked with the SS, those who helped him had a thin veneer of protection that enabled them to travel the streets to various ghettos, safehouses, and private homes, delivering identity documents and collecting valuables that could be used to bribe the Germans. “We would even hold meetings of our group at the fanciest restaurant in town,” Shatz says. “Often there would be tables of SS officers nearby, but they recognized Kasztner and left us alone.”

During this time, Shatz employed a strategy he called “seeking safety in the lion’s den.” His slight build and youthful appearance allowed him to pass as a teen below draft age, a role he embellished by wearing the cap of Hungary’s fascist youth movement, the Levente. He showed even more nerve when he walked into an Arrow Cross district office one day and inquired about a job and a place to stay. When asked if he was a Jew, Shatz cockily replied: “Would I be here if I were?”

He landed a bed in an apartment occupied by four Arrow Cross members and got a job working in a munitions factory, where he sabotaged the timers of shells and bombs. Soon his luck shielded him once again from the vagaries of the war: As he rushed home one night just before the citywide curfew, he found that a Soviet bomb had destroyed much of his apartment building, killing his Arrow Cross apartment mates.

Shatz continued to help Kasztner negotiate with Nazi officials to secure permission for Jews to leave for Switzerland. One of his duties was to visit the homes of wealthy Jews to collect funds and valuables to meet the Nazis’ escalating ransom demands, a task that brought him face to face with pure evil in the person of Adolf Eichmann, the top Nazi officer who managed the deportation and murder of millions of Jews during the war.

“I was directed to accompany Dr. Kasztner to deliver a suitcase of valuables to Nazi headquarters on Svabhegy, a ridge high above Buda,” Shatz says. “When I carried the heavy luggage into the office building near the end of a cog railway, I caught a brief glimpse of Eichmann’s ashen, sneering face. It was terrifying.”

Even as top Nazi officers began plotting their escapes from Budapest, the Arrow Cross thugs who now effectively ruled the city continued their campaign of terror. Seeking more Jews to exterminate, the group had begun modifying identity papers on a weekly basis to expose those who did not possess legitimate papers. But since the Nazi invasion the previous spring, the Jewish underground had employed a raft of engravers assigned to counterfeit the latest versions of required documents.

This was a critical task, but equally important, and much more dangerous, was the job of transporting the forged documents throughout the city to the Jews who relied on them for safety. Shatz continued to put his life on the line to fulfill that duty, dodging artillery shells, bullets, roving Arrow Cross gangs, and the bombs of Soviet aircraft.

On one such mission for the Hatzair in January 1945, he came quite close to death yet again after making his way to a Jewish sanatorium where one of the most active counterfeiting groups worked. He sought to have the birthdate on his identity papers altered in order to avoid a new government regulation authorizing males age 16 and above to be drafted for military service.

As he waited while the work was done, “something told me I was in danger,” Shatz says. “I retrieved my papers, even though they weren’t dry, and ran from the facility. Before I was a block away, I heard the screeching of brakes in front of the building, and a group of Arrow Cross thugs jumped out and rushed in.”

The next day, he read what had happened in a newspaper. Led by Pater Alfred Kun, a Catholic priest who had thrown in with the Nazis and the Arrow Cross, the thugs had ordered dozens of patients, physicians, and nurses to assemble and produce identity papers. Those carrying forged documents were summarily shot.

As Soviet troops tightened their grip on the city in early 1945, new dangers emerged. By February, Shatz says, the Russian soldiers had discovered that “by breaking down the walls, they could move down the street in relative safety.”

One freezing night, a squad of Red Army troops burst into the basement of the house where Shatz and some friends were staying and began to hammer at the wall, intent on moving to the next building. For some reason the wall held. The troops became furious, and Shatz recognized that his life and the lives of his friends lay in his hands. Using the fragmented Russian he had learned in his native Czechoslovakia, he tried to calm the soldiers.

“The squad leader grinned and said, ‘You, go up to the street, run to the next house, and break through the wall.’ It was an order, not a suggestion,” Shatz recalls. “I did as he ordered, running up a street lit only by whizzing tracer bullets.”

As he ducked into the entrance of the next apartment building, Shatz heard a gruff Russian voice shout, “Spion! Spion!” (Spy! Spy!) Feeling the barrels of machine guns prodding his back, he’d been surrounded by several Soviet soldiers seeking to remain undercover who had mistaken him for a Nazi scout. “I am no spy. I am a Jew,” Shatz replied.

A Russian voice then demanded that he say something in Hebrew. But Shatz was a lapsed Jew; he had seldom in his life even visited a synagogue. Shivering in the cold, he plumbed the recesses of his memory and pulled up a fragment of the essential ancient Jewish prayer: “Shema Yisrael, Adonai eloheinu!” (Hear, O Israel! The Lord is our God!) The gruff Russian soldier stepped forward and told his fellow soldiers, “He is okay. He is no spy.”

Shatz then led the Soviet troops to the apartment building’s basement and helped them break through the wall and reunite with their comrades in the basement next door to continue their attack up the street toward the Nazis and Arrow Cross troops. The young Jew had emerged unscathed from yet another brush with death.

After Shatz came back up from the basement, he was taken to the local Soviet army headquarters. There, his language skills paved the way for him to become a translator for the Russians.

In just a few weeks, the war in Europe would officially end. Of the more than 200,000 Jews trapped in Budapest during the Nazi occupation and Soviet siege, historians believe that fewer than 60,000 survived. Through a near–miraculous combination of luck, guile, bravery, intelligence, and resourcefulness, one of those survivors was Feri Shatz.

After World War II, Ferenc Shatz returned to his native Czechoslovakia, took a job as a journalist, and married a Czech woman. But when the Soviets subverted his homeland’s free government, he helped several Jews escape to Israel, which brought him under the suspicion of communist government officials. In 1958 he and his wife, Jarka, emigrated to the West as refugees. Shatz did not talk about his wartime experiences until the 1980s, when he learned about holocaust deniers and began to speak up. After a long career as a merchant and journalist in Lake Placid, New York, he retired with his wife to Williamsburg, Virginia. MHQ

William Walker is the author of Betrayal at Little Gibraltar: A German Fortress, a Treacherous American General, and the Battle to End World War I (Scribner, 2016).

[hr]

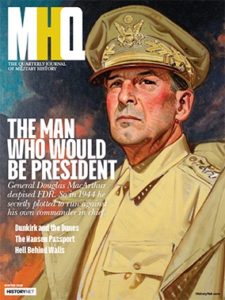

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Escape Artist