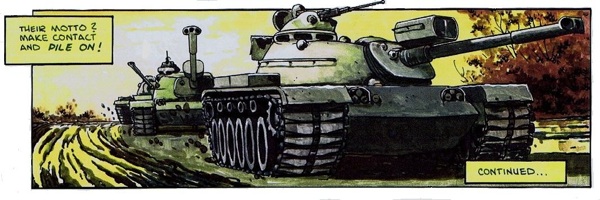

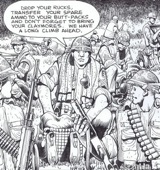

Don Lomax is a 35-year-plus veteran of the competitive world of comic and cartoon artists. He is also a veteran of a much tougher struggle—the Vietnam War. Drafted in 1965, the following year he found himself serving in Vietnam with the 98th Light Equipment Company. Notes and sketches he made during his time there led him to create a critically acclaimed “comic,” the graphic novel series Vietnam Journal, many years later. His words and artwork were literary napalm that burned away the sanitized versions of combat and soldiering found in traditional “war comics.” The images are often violent, the characters’ language at times profane; we asked for some of his tamer pages to run with this article.

Vietnam Journal garnered praise from Military Book Club, Publishers Weekly and numerous other sources, but it went out of print. Twice. Now the stories are being collected into graphic novel format and made available to readers again through Tranfuzion Publishing. HistoryNet’s editor Gerald Swick recently interviewed Don Lomax about his work, his children—two sons have served in the military, one of whom is still on active duty—and what led him to break traditional comic-book boundaries and present a more realistic war comic.

HistoryNet: How did you get into drawing comics and cartoons?

Don Lomax: There never was a time I ever considered doing anything else. Though I spent 20 years working on the railroad it was just to pay my bills while I pursued my “over-night“ success in the comics industry.

HN: Anyone who thinks comics are just cute stories for children hasn’t been in a comic book store in a very long time. You were among the writers and illustrators who pulled American comics into a brave new world, weren’t you?

DL: I’ve always loved comics. Though I am not much of a collector or patron now and haven’t been for years I still enjoy immensely a good read. And the comics of my childhood were delightfully fraught with guilty pleasures for a youngster. Vampires, werewolves, ghouls, and goblins, sex and violence were literally dripping from the pages. As youngsters our comic addictions were even sweeter knowing we were doing something we shouldn’t. I would hide them under my mattress and drag them out at night. Under the covers with a flashlight I would read them and scare the tarnation out of myself. My Dad always wondered why a perfectly good flashlight from the night before had dead batteries whenever he wanted to use it.

DL: I’ve always loved comics. Though I am not much of a collector or patron now and haven’t been for years I still enjoy immensely a good read. And the comics of my childhood were delightfully fraught with guilty pleasures for a youngster. Vampires, werewolves, ghouls, and goblins, sex and violence were literally dripping from the pages. As youngsters our comic addictions were even sweeter knowing we were doing something we shouldn’t. I would hide them under my mattress and drag them out at night. Under the covers with a flashlight I would read them and scare the tarnation out of myself. My Dad always wondered why a perfectly good flashlight from the night before had dead batteries whenever he wanted to use it.

Then came the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency Hearings in 1954. Sex and violence in comics was given a pivotal role in the proceedings as one of the primary causes for children’s hateful behavior. Comic book publishers, for fear of the heavy hammer of Big Government falling on their soft heads instituted the self-regulating Comics Code and all of the fun was gone from comics.

Those of us with a morbid need to be frightened found our outlets in the few non-code publications that remained. The Warren Black and Whites, Creepy, Eerie, Vampirella and True Detective. There was Blazing Combat and a scarce few others. But in the ’60s the underground movement began to grow, mostly due to the Comics Code restrictions. I sold my first professional work to the undergrounds and non-code magazines. The movement grew and my art found a home. Or maybe it was just the fact that my work didn’t fit the “cookie-cutter” comic styles of the big two, Marvel and DC—though I did work in Marvel’s assembly line, puppy-mill of artists for a few years in the early ‘90s inking some Sleepwalker and Punisher pages and I wrote the later books of Marvel’s series The ‘Nam—issues number 70 through 84, the final issue, I believe.

I cut my teeth in the smaller companies: First, Pacific, Warp Graphics, Apple, Fantagraphics, Eros, etc. I never got rich but it was a hell of a ride and I had a lot of fun. To say that I was one of the founding fathers of current comics might be stretching it. But I do like to think that I did my share, charged at the windmills of censorship and hypocritical piety. Though I would never let my own kids read such publications. That is where censorship belongs: in the hands of parents.

HN: While many Vietnam vets tried hard to push their memories away, you captured yours in graphic detail—very graphic detail, in fact. What drove you to do that?

DL: Maybe if I had some of the horrific experiences that some of the line troops had—those who were in the thick of battle and experienced lost buddies and suffered first hand—I would have thought differently. But bear in mind I was a REMF (Rear Echelon M***** F*****), I never even saw a live enemy or faced the traumas real soldiers were forced to endure. Most of the time I slept on a cot and had warm meals and counted the days. And except for a few truck rides up the hairy An Khe Pass or up Highway One to Bong Son, my Vietnam experience was pretty much a dud, hero-wise. But I do remember thinking, “Damn, this would make a good comic book!” at the time.

DL: Maybe if I had some of the horrific experiences that some of the line troops had—those who were in the thick of battle and experienced lost buddies and suffered first hand—I would have thought differently. But bear in mind I was a REMF (Rear Echelon M***** F*****), I never even saw a live enemy or faced the traumas real soldiers were forced to endure. Most of the time I slept on a cot and had warm meals and counted the days. And except for a few truck rides up the hairy An Khe Pass or up Highway One to Bong Son, my Vietnam experience was pretty much a dud, hero-wise. But I do remember thinking, “Damn, this would make a good comic book!” at the time.

HN: Your work pulls no punches about war, but that didn’t keep two of your children from entering the military. What do they say about Vietnam Journal?

DL: Now you’re talking about my favorite subject, my kids. My sons were both in the Army prior to Vietnam Journal. Where we were living job opportunities were minimal and it was the ’80s. No war, no rumors of war.

Bryan, my oldest, wanted to go in the military. I figured, Why not—he would do a three-year hitch and come out, get some of that good government-sponsored education and go on with his life. He became a Crew Chief and Mechanic on a Chinook and went off to Panama and didn’t come back for 8 years, a veteran of Operation Just Cause.

John, my second son, two years after his brother joined, followed in his footsteps. He MOSed (recieved a Military Occupation Specialty) as 11 Charlie, Mortarman. He later applied and was accepted to the Rangers. Later still, he applied and was accepted to Special Forces school and earned his Green Beret. He has been to Afghanistan twice and Iraq once and will be going back to Afghanistan again in the spring as a dog handler. He has 22 years in.

As to how they feel about Vietnam Journal, though they do not spend an inordinate amount of time praising it, I think they are proud of their old man’s work

HN: Vietnam Journal has had three publishers since its debut in November 1987. Tell us a little about its life on the comic book shelves and what’s happening with it now.

DL: I was doing a comic entitled Captain Obese for Warp Graphics when the company was bought out by Michael Catron and the name was changed to Apple Press. Mike, an advocate of the military and somewhat of a historian, asked if I wanted to do a regular comic about the war, and I jumped at the challenge. This was the days of Platoon and Full Metal Jacket and so on, nearly 15 years after combat troops left the ‘Nam. America was still wrestling with the whys and wherefores, trying to make sense of it all. The series did pretty good for a small-press, bargain-bin, no-name company. The original series ran 16 issues and spawned several spinoffs: Tet ’68, Bloodbath at Khe Sanh, Valley of Death, and High Shining Brass. Really, all but High Shining Brass were simply continuations of the original Vietnam Journal, only under different titles.

Two collections of the original work, Indian Country and The Iron Triangle, were published in graphic-novel form before Apple succumbed to the collapse in the comic market in 1994. I went on to other things and thought that it was over for Vietnam Journal. It had been a good run, though I didn’t get to finish what I had started out to do.

Then in 2001, Byron Preiss initiated the start-up of a new publishing house, I-Books, and approached me to reissue Vietnam Journal and Desert Storm Journal in graphic-novel form again. The book garnered a Harvey Award Nomination, but after one issue of Vietnam Journal and the complete book of Desert Storm Journal were out, Byron was tragically killed in an automobile accident and the I-book imprint went under, culminating in bankruptcy.

Then in 2001, Byron Preiss initiated the start-up of a new publishing house, I-Books, and approached me to reissue Vietnam Journal and Desert Storm Journal in graphic-novel form again. The book garnered a Harvey Award Nomination, but after one issue of Vietnam Journal and the complete book of Desert Storm Journal were out, Byron was tragically killed in an automobile accident and the I-book imprint went under, culminating in bankruptcy.

Vietnam Journal demise #2.

But it would not stay dead. Like the war ate at our American consciousness, the title would not go away.

I had stories left to tell. I took a rudimentary course in junior college and built my own Website and began to finish the Valley of Death series where it had been discontinued with only one chapter in print. It was available free of charge to anyone interested. I called the continuation, the Continuum. Gary Reed at http://www.Transfuzion.biz saw the Website and, being surprised I was still alive, he contacted me and asked if I wanted to reissue the series, this time to completion … we hope. At this time there are five volumes out, and we are expecting the rest to follow.

HN: Thanks for talking with us. Is there anything you’d like to add?

DL: Just that comics, like Hollywood movies, are entertainment. Unlike the historical publications World History Group publishes—which are event-driven—comics and movies are character-driven. Though I work very hard to make the comic as realistic as I can, it is, after all, a comic and intended for entertainment. Perhaps that is why Hollywood has such a love affair with comics, and it is growing every day. I hope the characters in my humble strip strike a cord and are as flawed and human, as tragic and heroic, as frustrating and funny as those I am trying to depict—America’s fighting men. It makes my day when a Vietnam vet walks up to me and simply says, “There it is.”

[nggallery id=62]