Those he passed paid scant attention to the man bicycling across St. Peter’s Square that early October day in Rome in 1942. Dressed in workman’s overalls, he rode straight through the gates of Vatican City, circled the fountains and pedaled past the gardens, seemingly unseen by the Swiss Guards. Not until he approached St. Martha’s House, a conclave for clerics, diplomats and pilgrims, was he finally stopped and questioned by Vatican policeman Anton Call.

The cyclist, a British sailor named Albert Penny, admitted to the carabiniere he had recently escaped from a prisoner of war camp in Viterbo, some 40 miles northwest of Rome. Instead of turning over Penny to counterparts in the Italian police, however, Call alerted Sir D’Arcy Osborne, British envoy and minister plenipotentiary to the Vatican. Osborne in turn petitioned Vatican authorities to allow the POW to remain within their walls, noting the papal state’s neutral status in the war then ravaging Europe.

Authorities granted permission, and Penny lived in Osborne’s apartment at St. Martha’s until formally exchanged for an Italian prisoner. The British seaman was the first of thousands in Italy to receive aid from what became known as the Rome Escape Line. Many such networks operated throughout Europe during World War II, but this one had the distinction of being run by a Vatican priest, an Irishman named Hugh O’Flaherty.

By war’s end O’Flaherty’s organization had saved an estimated 6,500 at-risk people, including escaped POWs, downed airmen, refugees, Jews and others. Those saved hailed from Britain, South Africa, Russia, Greece, the United States and more than 20 other countries. Almost all the civilians were Italians, many of them Jewish.

Perhaps most remarkable is that Nazi officials knew exactly what was going on. They just couldn’t catch Monsignor O’Flaherty in the act.

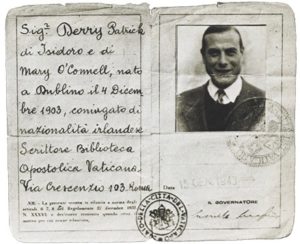

Hugh O’Flaherty was born in County Cork, Ireland, on Feb. 28, 1898, and grew up in Killarney, County Kerry, where his father was steward of the Killarney Golf Club. Young O’Flaherty pursued academics, eventually joined the priesthood and was posted to Rome in 1922, the year Benito Mussolini rose to power in Italy.

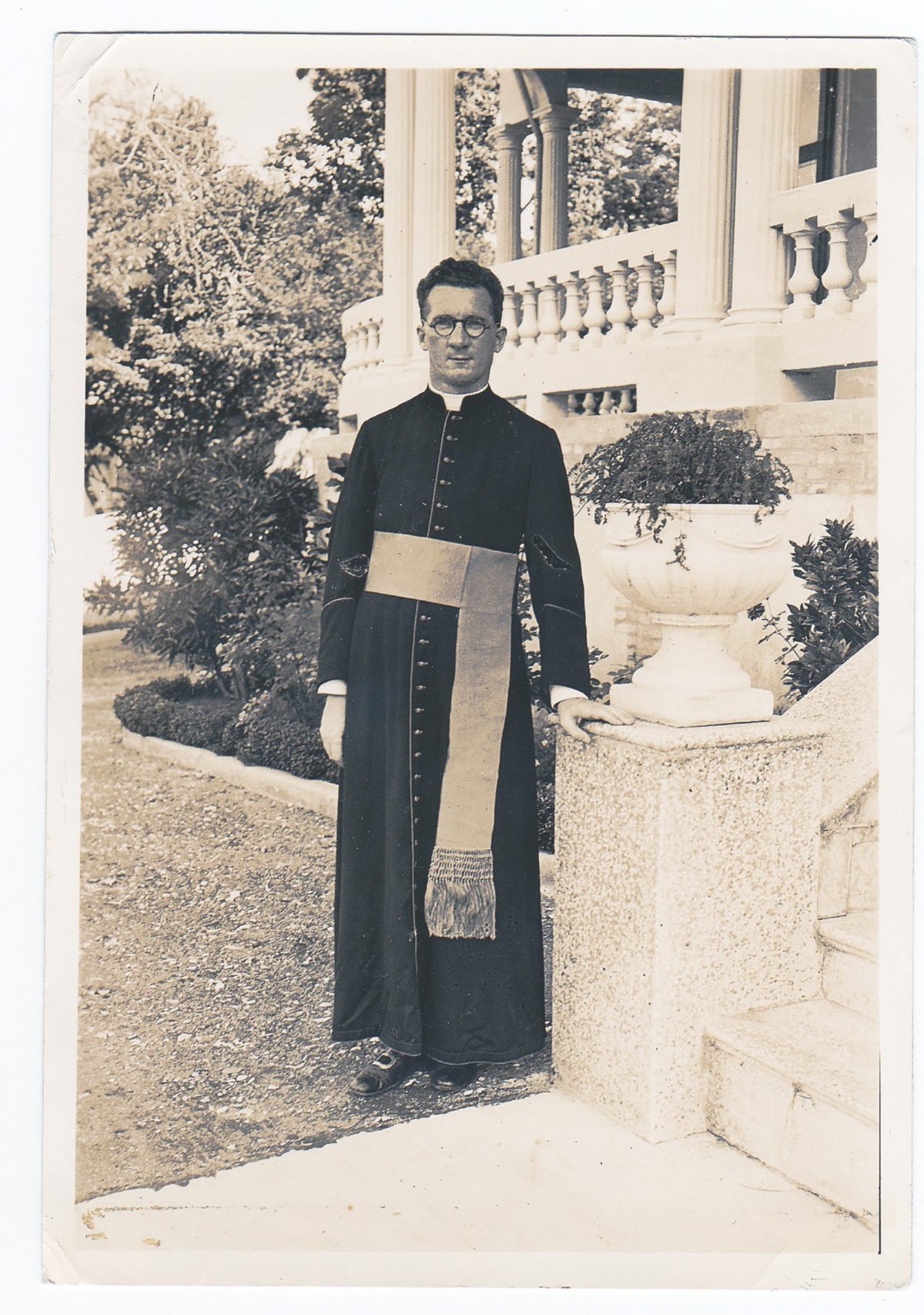

After his 1925 ordination O’Flaherty served as a Vatican diplomat in Egypt, Haiti, Santo Domingo (the present-day Dominican Republic) and Czechoslovakia before being recalled to Rome and appointed to the Vatican’s Holy Office. Named papal chamberlain in 1934, the Very Rev. Monsignor O’Flaherty became a familiar figure in Rome, appearing daily on the steps of St. Peter’s Basilica to read his breviary. The six-foot-two cleric was conspicuous in his black cassock and scarlet sash, and people were drawn to his Irish brogue, magnetic personality, ready smile and lively eyes set behind steel-rimmed glasses.

At the outset of the war, when Mussolini linked Italy to Germany as an Axis partner, O’Flaherty was assisting apostolic nuncio Monsignor Francesco Borgongini Duca, whom Pope Pius XII had tasked with checking on the welfare of inmates at POW camps. O’Flaherty assumed his new role with enthusiasm and compassion, and word soon got around about his discreet efforts to offer sanctuary and other aid. Those knowing of his “avocation” routinely approached the monsignor on the steps of St. Peter’s to tell him of escaped prisoners needing secure hiding places. O’Flaherty helped any and all who found their way to the Vatican, arranging to provide them with safe houses, food, clothing and, at times, even forged documents.

Having served in Rome for so many years, O’Flaherty had built a network of contacts in high society who could provide sanctuary. In a sense, Vatican City was a “safe house” unto itself. Under the 1929 Lateran Treaty, Italy had recognized the papal dominion as a sovereign state. The pact covered not only the 110 acres encompassing St. Peter’s, the Sistine Chapel, the extensive gardens, clerical housing and administrative offices, but also 50 acres outside the city walls, and it granted protected status to numerous “extraterritorial” buildings in Rome.

By late 1943, the Rome Escape Line had provided sanctuary to some 2,000 people in private homes, religious sites, colleges and other buildings throughout the Italian capital, as well as on outlying farms. Among the earliest hideouts was an apartment that backed up on the local SS headquarters. “Faith,” O’Flaherty reasoned, “they’ll never think of looking under their noses.”

Heading up the escape line was a “Council of Three”—O’Flaherty (code name “Golf”); Osborne (“Mount”), who provided the lion’s share of the funding, with money channeled from the British Foreign Office and a loan from the Vatican bank; and John May (“Giovanni”), Osborne’s butler, whom O’Flaherty once described as the “most magnificent scrounger I have ever come across.” Aiding the trio in their efforts were clergymen, sympathetic nobles and various friends of the Vatican, including a Swiss count, the wife of the Irish ambassador and Maltese widow Chetta Chevalier, who housed scores of escapees even while caring for her own children and elderly mother. Many of the monsignor’s fellow Irish clergy—priests and nuns alike—served as messengers.

In 1943 the council hired on British escapee Maj. Sam Derry, who later noted “the strangeness of this organization, in which soldiers and priests, diplomats and communists, noblemen and humble working folk were all operating in concord with a single aim, yet without any clearly defined pyramid of authority.” Derry ultimately became the escape line’s chief organizer.

When the Italian government stripped Mussolini of power in July 1943, the Germans rolled into Rome in force to keep a lid on the city and its people. One of the primary authorities tasked with enforcing Nazi control was Gestapo chief Herbert Kappler.

Born in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1907, Kappler had been a Nazi Party member since age 23. In 1943 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and named head of all Nazi SS and police units in Rome. Kappler was equally committed to rounding up Jews for deportation and hunting down those Allied personnel who had escaped from Italian POW camps after the nation’s army surrendered. Well aware of O’Flaherty’s activities, he was determined to get the priest, dead or alive.

Kappler offered a 30,000-lire bounty for information leading to O’Flaherty’s capture. But he could not arrest him inside Vatican City. In the meantime, the colonel had soldiers paint a white boundary line around the papal state, implicitly warning O’Flaherty of dire consequences should he stray outside. Ernst von Weizsäcker, German ambassador to the Vatican, overtly cautioned the monsignor. “If you ever step outside Vatican territory again, on whatever pretext,” he told O’Flaherty, “you will be arrested at once.” For his part, Pietro Koch, head of the fascist police in Rome, threatened to torture and execute the priest, if given the opportunity.

Kappler fomented several plots to kidnap or kill O’Flaherty, including one in which a pair of plainclothes SS henchmen planned to attend Mass, then manhandle the priest across the boundary line, where O’Flaherty was to be “shot while attempting to escape.” May got wind of the latter scheme and suggested the priest refrain from emerging on the steps of St. Peter’s and lie low a while. “What, me boy,” O’Flaherty replied, “and let them think I am afraid? So long as they don’t use guns, I can tackle any two or three of them with ease, though a scrap would be a bit undignified on the very steps of St. Peter’s itself, would it not?” With the help of friendly Yugoslav partisans, May waylaid the would-be kidnappers beforehand.

No matter the threat, O’Flaherty disregarded his own safety. “The monsignor,” Osborne once observed, “simply accepts at face value everyone who asks him for assistance and immediately gives all help he can, whatever the risk. I worry about him sometimes, but there seems to be no way of convincing him that his own life is well worth preserving.”

Despite German vigilance, O’Flaherty continued his work, often walking the streets of Rome in disguise, one day as a street cleaner, the next as a postman. Compatriots took to calling him the “Pimpernel of the Vatican,” after the fictional “scarlet” hero of the French Reign of Terror who slipped through the streets of Paris in disguise to rescue aristocrats sentenced to the guillotine. The monsignor sometimes met personally with escapees, taking along spare clerical robes with which to disguise them for entry into the Vatican.

One day as O’Flaherty arrived at the Roman estate of Prince Filippo Andrea Doria Pamphili—one of the nobles who helped with funding—waiting Gestapo agents recognized the priest and alerted Kappler, who soon rolled up outside the Palazzo Doria with a large force. The prince’s wary secretary alerted O’Flaherty, who dashed down to the basement, where coalmen were busy making a delivery. One agreed to help, remaining in the cellar while the disguised monsignor walked out to the delivery truck. After smudging his face in coal dust and tossing his clerical clothes into a coal sack, O’Flaherty coolly strolled right past the Gestapo.

After taking the backstreets home to the Vatican, the priest phoned the prince.

“Are you well, me boy?” he asked.

“Fine now,” came the reply. “Someday you must tell me how you did it. I am afraid Colonel Kappler is a very angry man. He spent two hours here, and he did say that if I happened to see you, I was to say that one of these days he will be entertaining you.”

On March 23, 1944, in the wake of the Allied landings at Anzio, the emboldened Italian resistance ambushed an SS police regiment with an improvised explosive device, killing nearly three dozen policemen. In reprisal Kappler was ordered to execute 10 Roman citizens for every German soldier killed. The next day, under his direction, an SS death squad carried out the order, executing 335 Italian prisoners in the tunnels of disused quarries at Ardea, some 25 miles south of Rome. German engineers then sealed the caves with explosives.

Neither the continued threats nor such atrocities deterred O’Flaherty or his escape line cohorts. By spring 1944 they were housing some 3,500 people in various sites across Rome, and by war’s end the total number of people saved had soared to 6,500.

the Germans, and twice he escaped. In 1943 he approached the Vatican for help in aiding POWs secreted among the hills following fascist Italy’s collapse. He ultimately became the Rome Escape Line’s chief organizer. (Boston Public Library)

After the war an Italian military tribunal convicted Kappler for his role in the Ardeatine massacre, sentencing him to life imprisonment at the Aragonese-Angevine fortress in Gaeta. Ever the intercessor, O’Flaherty exchanged letters with his Nazi nemesis during the latter’s imprisonment and regularly visited Kappler to discuss religion and literature. In 1959 the priest helped the German inmate fulfill his requested conversion to Catholicism.

Kappler’s wife divorced him after he entered prison. He later engaged in a lengthy correspondence with German nurse Anneliese Walther, marrying her in a prison ceremony at Gaeta in 1972. Three years later the 68-year-old inmate, having been diagnosed with terminal cancer, was moved to a military hospital in Rome. Due to her husband’s deteriorating health, Anneliese Kappler was granted virtually unrestricted access to his room, ostensibly to nurse him. While visiting her cancer-ridden spouse in August 1977, she smuggled him out to her car in a large suitcase and drove him back to West Germany. Given his condition, authorities refused to extradite Kappler. He died at home in Soltau on Feb. 9, 1978.

Having suffered a stroke in 1960, O’Flaherty had returned to Ireland to lead a quiet life, highlighted by golf outings and expressions of gratitude from some of the 6,500 people he had saved. The Allies honored him with many civilian awards, including appointment to Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) and the U.S. Medal of Freedom with silver palm.

Hugh O’Flaherty died on Oct. 30, 1963, and is buried in Cahersiveen, County Kerry, where he lived out his life in the care of his sister, Bridie Sheehan. Twenty years later Gregory Peck portrayed the monsignor in the made-for-TV war drama The Scarlet and the Black, with Christopher Plummer as Kappler. In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of O’Flaherty’s death, Killarney officials unveiled a memorial [hughoflaherty.com] in recognition of their hometown hero’s achievements. Mounted in front of plaques that recount his wartime exploits, the life-sized bronze statue of the Pimpernel of the Vatican stands in midstride just outside Killarney National Park.

New York–based Norm Goldstein is a regular contributor to Military History. For further reading he recommends The Rome Escape Line, by Sam Derry; The Vatican Pimpernel, by Brian Fleming; and Hide & Seek: The Irish Priest in the Vatican Who Defied the Nazi Command, by Stephen Walker.