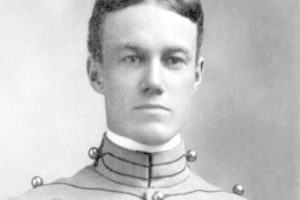

Musician Calvin Pearl Titus

U.S. Army

Medal of Honor

Boxer Rebellion

August 14, 1900

Tens of thousands of young cadets have passed through the hallowed halls and across the parade grounds of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., since its 1802 founding, but only one, Calvin Pearl Titus, received the nation’s highest award while enrolled at the school.

Born in Vinton, Iowa, on Sept. 22, 1879, Titus moved with his father to Oklahoma at age 10 after his mother’s death and later lived with his aunt and uncle, who were evangelists with the Salvation Army. A self-taught musician who learned to play the violin and coronet, Titus honed his technique at prayer meetings with his uncle’s traveling band.

With the sinking of the battleship USS Maine and outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898 the patriotic young traveling musician spontaneously joined the 1st Vermont Volunteers as a bugler. He never saw combat, though, as he contracted malaria while awaiting deployment. After his discharge Titus returned to the Midwest, but the restless teen soon learned the Army was seeking troops for occupation duty in the formerly Spanish-ruled Philippines. In April 1899 he enlisted in the 14th U.S. Infantry Regiment and shipped out to Manila as a musician and chaplain’s assistant. Within a year his regiment was sent to China with an 18,000-strong multinational force tasked with rescuing besieged diplomats and foreign nationals in Peking at the height of the Boxer Rebellion.

The men of the 14th Infantry arrived outside their assigned city gate on Aug. 14, 1900, immediately drawing heavy fire from imperial troops atop the 30-foot outer wall and an adjacent tower. When regimental commander Colonel Aaron S. Daggett asked for volunteers to scale the wall and clear it of enemy troops, Titus stepped forward. “With what interest did the officers and men watch every step,” recalled Daggett, “as he placed his feet carefully in the cavities and clung with his fingers to the projecting bricks.” What followed is summarized in Titus’ Medal of Honor citation, among the shortest on record: “Gallant and daring conduct in the presence of his colonel and other officers and enlisted men of his regiment; was first to scale the wall of the city.” Titus’ heroics encouraged other members of his company to clamber up and lay down suppressing fire, thus enabling American and Russian troops to enter the city.

The next year Titus entered the U.S. Military Academy on a presidential appointment, and on March 11, 1902, at a ceremony marking West Point’s centennial, President Theodore Roose-

velt personally pinned the Medal of Honor on the first-year cadet’s parade dress uniform. “Now don’t let this give you the big head!” quipped Roosevelt. Following the ceremony a fellow cadet approached Titus, admired his medal and exclaimed, “Mister, that’s something!” The cadet’s name was Douglas MacArthur.

Titus had an active career following his 1905 graduation. He served several more years in the Philippines, participated in the relief of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire, fought forest fires in Yellowstone Park, helped pursue Pancho Villa in 1916 and served in occupied Germany after World War I. He later directed the ROTC battalion at Iowa’s Coe College, retiring in 1930 as a lieutenant colonel. Titus, 86, died in San Fernando, Calif., on May 27, 1966, and is interred at Forrest Lawn Memorial Park in the Hollywood Hills.