When a failed coup d’état launched by right-wing generals split Spain into warring factions in 1936, the ensuing civil war became an international cause célèbre that attracted legions of foreign volunteers to the beleaguered Spanish Republic. The soldiers in the “International Brigades” they formed would be immortalized in works by George Orwell, who was invalided home after fighting on the Aragon front, and Ernest Hemingway, who covered their exploits as a correspondent for the North American Newspaper Alliance. Not as well remembered as their white peers, however, are the hundred or so African Americans who found, in the American Lincoln Battalion, a kind of equality they’d been denied at home. Most prominent among these men was Oliver Law, a black U.S. Army veteran who would make history in Spain as the first man of color to command an integrated group of American soldiers.

Born on October 23, 1900, Law grew up in West Texas and in 1919 joined the 24th U.S. Infantry Regiment (Colored)—one of the six all-black “Buffalo” regiments organized after the Civil War. His enlistment came at an especially tense time in the 24th Infantry’s history. Only two years before, more than 100 soldiers in the regiment had mutinied in Houston during a race riot over abusive treatment at the hands of local police. More than a dozen white civilians and policemen were killed, along with a lesser number of black soldiers. In the ensuing months, 110 of the regiment’s members were convicted of mutiny, and 19 were executed. Against this background of discontent and tension, Law would go on to serve six uneventful years on the Mexican border with the unit before leaving the military in search of civilian work. It was 1925, and difficult times lay ahead for both Law and his country.

After a few unhappy years working at a cement factory in Bluffton, Indiana, Law went to Chicago to seek lasting employment. Just as he seemed to have found a source of steady money, as a driver with the Yellow Cab Company, the Great Depression hit. With his long periods of unemployment, interrupted only briefly by jobs on the docks and in restaurants, Law became a social and political activist. Gradually becoming more radical, he first joined the Chicago chapter of the Longshoreman’s Association, followed by the International Labor Defense advocacy group, and finally the Communist Party. Law saw communism as the antidote to the many inequities and indignities he had endured as a black man and as a union worker. As a labor organizer, Law fought for the rights of Chicago’s working-class residents in housing disputes with their landlords and the government.

These activities attracted the attention of the Chicago Police Department’s “Red Squad,” which harassed Law and his fellow leftists whenever possible. In 1930 threats turned to violence: The police beat Law so badly that he was hospitalized. Despite this intimidation, Law became a leading member of the black left wing in Chicago, married the daughter of Claude Lightfoot, a prominent black communist, and found a steady source of income from the Works Project Administration. But in October 1935, with the forces of fascism on the march, Law heard a new call to action.

After months of troop buildups, Benito Mussolini, Italy’s fascist dictator, brushed aside international outrage with claims of “national interest” and ordered his army to invade Ethiopia. Nowhere in the United States was anger over the invasion more acute than on Chicago’s South Side, where blacks rallied around the plight of Africa’s one remaining uncolonized nation. Law was one of several speakers to stand on the city’s rooftops and address marchers at an unauthorized “Hands Off Ethiopia” rally.

Law soon pursued more active resistance to Italy’s aggression. As he and hundreds of other African Americans organized to join the army of Ethiopia’s emperor, Haile Selassie, the under-equipped Ethiopian forces buckled under the Italian onslaught, which included chemical weapons and advanced military machinery. Thus, the volunteers were left ready to fight but had no battlefield. They would not have to wait long.

When word reached Law and his compatriots in 1936 that the same Italian soldiers who had subjugated Ethiopia would now be deployed to aid General Francisco Franco’s “Nationalist” forces in Spain, they saw a second chance to strike a blow against colonialism and international fascism. Soon, Nazi Germany, under Adolf Hitler, would also come to Franco’s aid. But it was unclear how long the “Republican” cause in Spain—a ragtag collection of anarchists, socialists, communists, and democrats—could hold its own against Franco’s better equipped and better trained forces.

Law got his passport on January 7, 1937, and on the 16th left for Europe aboard the SS France. He and 90 or so black comrades were in the minority on the ship, and even more so in Spain. Of the idealists and adventurers who made up the soon-to-be-christened Abraham Lincoln Battalion, most were white; the majority of those were students, and a quarter were Jewish. They were nevertheless united by a common belief in their cause; their solidarity was further strengthened in the face of the U.S. government’s threat of confiscating their passports for breaking with their country’s noninterventionist policy on Spain. It was a heady time for the black Lincolns, who were not only treated equally by their white counterparts in the battalion but also saluted and celebrated by many of the Spanish civilians they encountered.

But they would not have much time to bask in their newfound freedom. With Franco’s armies advancing to the north of Madrid, the Republic’s military leadership had decided that the International Brigades were needed immediately to blunt the Nationalist offensive in the Jarama Valley, just east of the capital. Hastily trained and younger on average than any of the other brigades in the coalition, the soldiers of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion turned to the experienced Law for leadership. But the Lincolns, in Spain for less than two months, suffered 65 percent casualties between their initial counterattack and their subsequent defensive efforts.

Shortly before the soldiers in the shattered battalion were removed from the front, they confronted one of the war’s cruelest ironies. Rather than facing the elite Italian companies of Franco’s army, the Americans found themselves grappling with Franco’s colonial soldiers—native levies from the Spanish colony of Morocco. These soldiers had been lured to fight under the Nationalist banner by promises of good pay and false rumors that the Republic intended to abolish Islam in the name of communist atheism. The great pathos and confusion of this violent meeting between black Americans and the very Africans they had intended to free from colonial oppression was captured by poet Langston Hughes, whose time among the Lincolns inspired him to write, in his “Letter From Spain,”

We captured a wounded Moor today.

He was just as dark as me.

I said, Boy, what you been doin’ here

Fightin’ against the free?

The fact that these Moroccan regulares were deployed in dangerous missions in lieu of white troops reinforced for some Lincolns the righteousness of their cause. Not long after his musings on the Moroccans, Hughes returned to his theme: “Fascists is Jim Crow people, honey / And here we shoot ’em down.” The battle in Spain was thus, for Law and his fellow black American volunteers, a battle against the injustice that they had faced at home. Nevertheless, members of the battalion were relieved to be pulled away from the stalemate at Jarama in late February to rest and regroup ahead of a July thrust at Brunete, a small town 15 miles west of Madrid.

In the weeks that followed, a stream of American volunteers helped to replenish the ranks of the Lincolns. But many of the battalion’s officers had been reassigned or lost as casualties. Vacancies—most important, that of the commanding officer—would need to be filled rapidly if the unit was to be ready for the coming offensive.

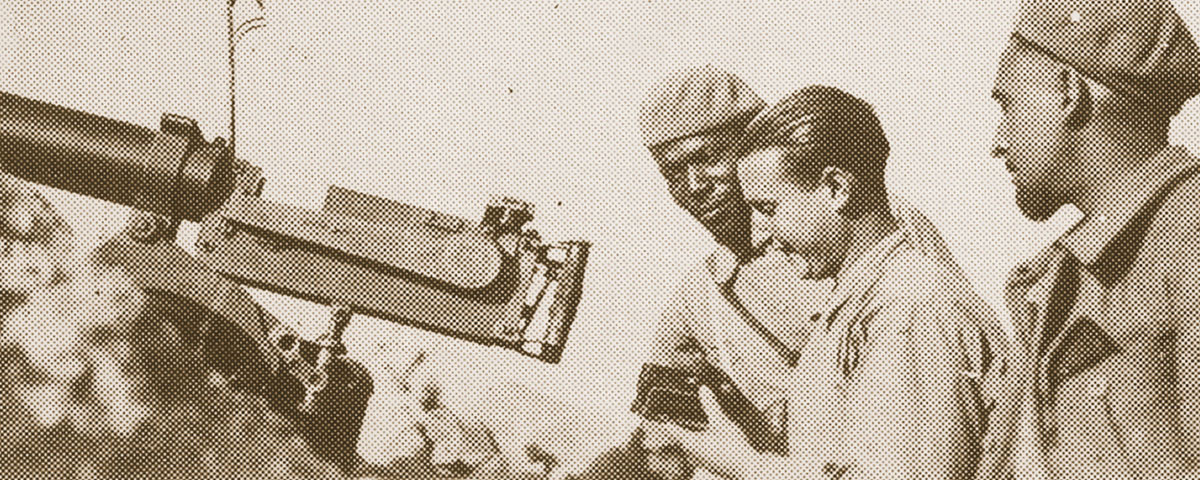

On June 12, 1937, Oliver Law was chosen by popular assent to lead the battalion. (In Spain, Law is reported to have said, “I can rise according to my worth, not my color.”) It was a promotion that rewarded the grit and competence under fire that Law had demonstrated at Jarama. Made machine-gun commander at the height of the fighting there, Law had proved himself a rock-solid leader. One Lincoln veteran would remember him as both well liked and well respected, even going so far as to call him “the best battalion commander in Spain.”

Illustrating the difference between Law’s new life and the world he had left behind, the color of his skin proved an unavoidable object of attention for American visitors to the battalion in a way that it did not for the Lincolns themselves. Shortly after taking command, Law was confronted by one such visitor, an American colonel from the South who inquired as to whether he knew that he was wearing a captain’s uniform. Law responded with a dignified affirmative and, when the bewildered colonel offered him the lukewarm congratulation that his people must have been proud of him, Law replied, “I’m sure they are!” Certainly, command of a battalion was a far cry from the six miserable years that he had spent serving exclusively white officers along the Texas-Mexico border.

Sadly, while both popular and historically remarkable, Law’s command was brief. When the Brunete offensive was finally launched, the Lincolns were repeatedly ordered to advance into the teeth of a series of well-defended enemy positions. Though he faltered at first in the face of the heavy Nationalist opposition, Law quickly recovered and sought to encourage his men by example. Once again, he was in front when the fighting turned tough. His luck ran out on July 9 as he led an attack on a position known as “Mosquito Ridge.” Running ahead of his men as they clambered up the hill under machine-gun and rifle fire, Law was an easy target. Hit twice by enemy fire as he attempted to urge the Lincolns on, the badly bleeding Law was carried back—against his own demands that his stretcher-bearers focus on the men who might still be saved. He was buried with respect under a grave marker, now lost, that proudly declared him to be “the First Negro to command American white soldiers.”

Oliver Law’s story has since largely faded into obscurity. In the year that followed his death, the Lincolns would suffer further losses as the Republican cause slowly unraveled. Eventually returning to a country whose government branded them “premature anti-fascists,” the American volunteers who managed to escape Franco’s eventual victory found few in the United States who were willing to listen to their praise for the man they had turned to for leadership during the two defining battles of their Spanish service.

Those who did pay attention to Law’s story found that his race and personal politics stood in the way of commemorating his achievements. Paul Robeson, having himself returned from the Christmas tour of Republican Spain in which he had first heard of Oliver Law from his surviving comrades, struggled in the following years to bring to the screen a film that would do justice to the legacy of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and its first black commander. Despite Robeson’s draw as an internationally acclaimed actor and musician, the Hollywood executives whom he petitioned for support turned a deaf ear to his idea, leaving Robeson to complain that “the same interests that block every effort to help Spain control the motion picture industry.” Robeson’s personal assistant later cited the failure of his plans to bring Law’s story to the public as the cause of his eventual withdrawal from the movie business.

Likewise, those interested in the story of the integration of the U.S. military have focused on President Harry S. Truman’s 1948 reforms of the armed forces and ignored Law’s election in Spain a decade earlier. With the Spanish Civil War increasingly in vogue with modern historians, however, it seems possible that Oliver Law’s achievement will finally begin to garner the attention it deserves. MHQ

Piers Brecher has a degree in history from the University of Chicago and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Oxford University. This article is adapted from an earlier work that appeared in The Gate, the student-run political science magazine of the University of Chicago.

This article appears in the Autumn 2017 issue (Vol. 30, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Lost Leader

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!