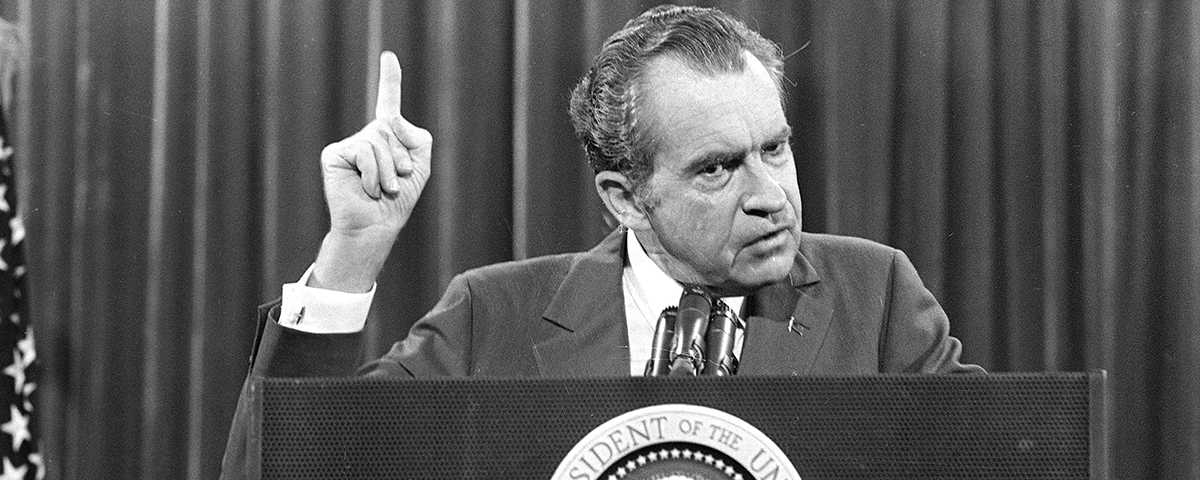

Did Richard Nixon secretly try to scuttle President Johnson’s peace-talk plan days before the 1968 presidential election? Recent evidence supports an unpublished story that he did

Beverly Deepe arrived in Vietnam as a 26-year-old reporter in 1962 and remained for seven years, becoming one of the longest-serving Western journalists to cover the war. As a freelancer early in the war, she explored the life and problems of the South Vietnamese in rural villages. In 1968, reporting for the Christian Science Monitor, the Nebraska native covered the Tet Offensive and Khe Sanh and pursued an unlikely lead she received from South Vietnamese sources a week before the U.S. presidential election: that the Richard Nixon camp was undermining President Lyndon Johnson’s three-point peace plan. In an excerpt from her memoir Death Zones and Darling Spies, Beverly Deepe Keever explains how the politically explosive revelations were softened when the story ran on election day, and how information declassified in 2008 now seemingly confirms the story, 45 years after LBJ’s private allegations to the Republican camp that Nixon was guilty of treason and had“blood on his hands.”

I left Khe Sanh just as U.S. bulldozers and explosives were demolishing the combat base so that it could be abandoned. Back in Saigon I wrote and airmailed to Boston a three-part series [about the siege at Khe Sanh for the Christian Science Monitor] that was later submitted along with the Monitor’s forms and letters nominating me for the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting.

Describing my June series as “unique in-depth reporting of complex and hazardous events,” managing editor Courtney Sheldon in his nominating letter also summed up some of my work throughout the year:“During 1968, Miss Deepe produced no fewer than 18 series of major articles on Vietnam for the Monitor, plus her regular string of daily articles. Among the best examples of her work under combat conditions was a series of six articles (March 20–27) from Khe Sanh on the plight of the encircled Marines there….Indeed, she traced the pattern of conflict all the way from the man in the Khe Sanh dugout to General [William] Westmoreland in Saigon and the Pentagon in Washington.”

The shock and awe of the Communists’ Tet blitz was on the U.S. “leadership segment”—the press, politicians and official Washington, according to a well-established polling firm. Clark Clifford, who had replaced Robert McNamara as secretary of defense on March 1, 1968, explained, “Tet hurt the administration where it needed support most, with Congress and the American public—not because of the reporting, but because of the event itself, and what it said about the credibility of American leaders.”Within Johnson’s official circles the psychological shock produced by Tet was profound. “The pressure grew so intense that at times I felt the government itself might come apart at its seams,” Clifford, the 61-year-old confidant to several U.S. presidents, explained.“There was,” he said,“something approaching paralysis, and a sense of events spiraling out of control of the nation’s leaders.”

Some linked the loss of credibility to Johnson’s own mismanaged public relations campaign months earlier. “The adverse impact of Tet on the United States government and its policies would never have been as serious as it was if the Johnson Administration had not spent the better part of the preceding fall in a massive propaganda campaign to raise the level of American support by [sic] the war with a flood of reports and public appearances by General Westmoreland, Ambassador [Ellsworth] Bunker and others,”a veteran Washington journalist explained. He reasoned,“To say that the press was responsible for the impact of the Tet offensive is to overlook the role of the government itself.”

On March 31, 1968, the leadership paralysis was broken when Johnson made twinned surprise announcements on nationwide television: He was declaring a halt to the bombing in North Vietnam except above the demilitarized zone so as to begin peace talks, and he would not seek reelection. Perhaps prompting Johnson’s decision was a draft memo from his most trusted advisers dated Feb. 29, 1968. In it they argued against further escalation of the war by using words Peter Arnett had gathered at Ben Tre during Tet: More escalation would make it “difficult to convince critics that we are not simply destroying South Vietnam in order to‘save’ it and that we genuinely want peace talks.” General [Vo Nguyen] Giap interpreted Johnson’s decision to decline a reelection bid to be “the end of the period in which the American imperialists considered themselves to be a superpower, and the collapse of their role in the world.”

Not so much because of Tet, the year 1968 was significant because of the U.S. economic crisis caused by a run on the dollar and gold resulting from Johnson’s spending on both the Vietnam War and his cherished Great Society programs, according to U.S. political economist Robert M. Collins. Collins argues that the U.S. economic crisis of 1968 “both revealed and contributed to the passing of postwar U.S. economic hegemony.” He called 1968 the year“the American Century came to an end.”

After Johnson’s stunning announcement that he would not seek reelection, Khe Sanh had lost its political significance. Officials in Saigon largely viewed the besieged base as important to the Communists only as a hinge to swing the American political nominations or elections. Three days later North Vietnam agreed to preliminary peace talks, and a month later, on May 3, both Hanoi and Washington agreed to begin discussions in Paris. On August 8 Richard Nixon accepted the Republican Party’s presidential nomination and promised to bring an honorable end to the war in Vietnam.

During October 1968, I was busier than usual covering the impact of a talked-about permanent bombing halt, which was Hanoi’s precondition for entering into peace talks with the allies. Most of my dispatches were published on page 1, often leading the Monitor. I interviewed senior military commanders along the DMZ and in Saigon, secured comments from Western diplomats, including one who had recently visited Hanoi, and sought input from other sources who assessed troop movements in Laos. At the same time I was synthesizing reports that Pham Xuan An [a stringer hired to help with oral and written translations] had gleaned from sources inside and outside the palace and the Vietnamese High Command.

Then, out of the blue, I learned of such outlandish rumblings that on October 28 I sent an advisory to the Monitor’s overseas editor, [Henry S.] “Hank” Hayward:“There’s a report here that Vietnamese Ambassador to Washington Bui Diem has notified the Foreign Ministry that Nixon aides have approached him and told him the Saigon government should hold to a firm position now regarding negotiations and that once Nixon is elected, he’ll back the Thieu government in their demands. If you could track it down with the Nixon camp, it would probably be a very good story.”I was so busy I had no chance to remember my assist eight years earlier in the NBC studios when my boss, Sam Lubell [with whom she had polled voters in key precincts about the 1960 presidential election], had predicted Nixon would lose the presidency to John Kennedy. Now, Nixon was facing Democrat Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who was saddled with President Lyndon Johnson’s increasingly controversial Vietnam policy. I received no response to my cable from Boston.

Three days after my advisory, on October 31, Johnson announced that he had ordered a complete end to the bombing of North Vietnam within 12 hours and that the date for the first negotiation session with Hanoi was set for November 6, the day after the U.S. presidential election. Johnson’s speech was received in Saigon on November 1, which, as I reported, many Vietnamese viewed as an ill-timed insult because it was made on Vietnam’s National Day and the anniversary of the Kennedy administration’s support for the overthrow of President [Ngo Dinh] Diem.

Then, just four days before the U.S. election, President Thieu surprisingly rejected Johnson’s peace initiative. In a bombshell televised speech before the National Assembly on Vietnam’s National Day, Thieu announced that South Vietnam would not send delegates to negotiate in Paris by November 6; he feared the Viet Cong’s National Liberation Front would be seated as a legitimate coequal of his government. I reported that his speech was a direct rebuke to President Johnson. “In effect, Mr. Thieu said LBJ double-crossed him,” one longtime Asia observer told me. “And Mr. Thieu is pretty nearly right.”

To explain Thieu’s stunning announcement, I cabled Hayward on November 4: “Purported political encouragement from the Richard Nixon camp was a significant factor in the last-minute decision of President Nguyen Van Thieu’s refusal to send a delegation to the Paris peace talks—at least until the American Presidential election is over.” I relied mostly on “informed sources”for my scoop—an eye-opening exclusive news report—and added that “the only written report about the alleged Nixon support for the Thieu government was a cable from Bui Diem, Vietnamese ambassador to Washington,” confirming what I had asked Hayward to check out days earlier.

But my momentous scoop was not published. Hayward cabled back that the Monitor had deleted all my references to Bui Diem and to the“purported political encouragement from the Nixon camp,” which, he wrote, “seems virtual equivalent of treason.”

Hayward could not have known then, but his description of Nixon’s “virtual equivalent of treason” was being privately echoed at the time by Johnson when he sputtered: “It would rock the world if it were known that Thieu was conniving with the Republicans. Can you imagine what people would say if it were to be known that Hanoi has met all these conditions and then Nixon’s conniving with them kept us from getting it.”

Hayward told me within a day or so:“The alleged Nixon involvement was interesting but needed confirmation from this end—which was not forthcoming—before we could print such sweeping charges on election day. It was a good story nonetheless, and you get major credit for digging it out.” Knowing the time-honored journalistic tradition of fairness, I understood when Hayward told me that without such confirmation, the Monitor had “trimmed and softened” my lead. The Monitor’s substitute lead simply implied that Thieu had acted on his own. Upon receiving the Monitor’s Western edition days later, however, I saw my supposed-to-be scoop relegated to page 2, with no mention of Nixon, under a one-column headline. I could hardly recognize it.Yet 44 years later I was stunned to learn that President Johnson had indeed read and agonized over my lead with his top aides. Just as this book was being readied for publication, I was queried about my scoop’s Nixon-Thieu connection by veteran investigative reporter Robert Parry. On March 3, 2012, Parry published an amazing exposé on his online investigative news service headlined: “LBJ’s ‘X’ File on Nixon’s ‘Treason.’” Parry also included links to the telltale documents he had uncovered. Although I had already pieced together from other sources much of his story line about Nixon’s maneuvering for my book, I had never suspected what Parry revealed about my own unpublished scoop.

Parry had opened a manila envelope in LBJ’s presidential library in Austin, Texas, labeled the “X Envelope.” In it he found dozens of “secret”and“top secret”memos, transcripts of audiotapes, FBI wiretaps and National Security Agency intercepts. Johnson had amassed the documents and, before he died on Jan. 22, 1973, had given them to National Security Adviser Walter Rostow. In turn Rostow labeled the manila mailer and inserted his top secret letter instructing the LBJ Library director not to open the X Envelope for 50 years from June 6, 1973—that is, until 2023. The librarians waited only 21 years, until July 22, 1994, to open the X Envelope and begin declassifying its contents.

The documents in the X Envelope reveal an even closer connection between Thieu and the Nixon camp than I had made in referring to Ambassador Bui Diem in my scoop, Parry details. That connection was Anna Chennault, the China-born widow of the U.S. General Claire Chennault, who had commanded the volunteer Flying Tigers to fight the Japanese in World War II. [Anna Chennault] was chairwoman of the Republican Women for Nixon in 1968 and was a driving force in the China Lobby that pushed for U.S. support for Taiwan. Known in the White House at various times as “Little Flower” or “Dragon Lady,”she recalls in her autobiography how she received a cable from Nixon in spring 1967 asking her to visit him in his New York apartment, where he disclosed his plans to run for president the next year and flattered her into agreeing to help him.

With the campaign beginning, Chennault flew again to New York to see Nixon, this time with Bui Diem, where they were joined by John Mitchell, who became what she describes as “commander in chief” of Nixon’s campaign. She quotes Nixon as having told Bui Diem that she was their mutual friend so that “if you have any message for me, please give it to Anna and she will relay it to me and I will do the same in the future.” He added, “If I should be elected the next President, you can rest assured I will have a meeting with your leader and find a solution to winning this war.”She also traveled privately to Vietnam as a columnist for a Chinese daily “while continuing to keep Nixon and Mitchell informed about South Vietnamese attitudes vis-à-vis the peace talks” and about her“many encounters with President Thieu.”

Other sources note that“almost every day”in the week leading up to the election, Chennault was telephoned by Mitchell, urging her to keep Thieu from going to Paris to help the Democrats get the Paris peace talks started. She relayed that and numerous other messages to Thieu, pleading with him to “hold on” instead of going to Paris.

Spookily, Johnson knew of her messages to Thieu because he had ordered the FBI to place Chennault, an American citizen, under surveillance and to install a telephone tap on the South Vietnamese Embassy, both illegal activities that the U.S. government regularly conducted but were kept secret for national security reasons.

Johnson and Rostow had become alarmed that Nixon was seriously colluding with Thieu to sabotage the peace talks, Parry reports, when on October 29 they learned from “a member in the banking community” in New York who was “very close to Nixon” that Wall Street bankers were sizing up that Johnson’s peace initiative would fail, [and] that the “U.S. would have to spend a great deal more—a fact which would adversely affect the stock market and bond market.”

Two days later—and just hours before his 8 p.m. televised address—Johnson began calling key senators who might warn Nixon’s people to stop “messing around with both sides,” explaining, “Hanoi thought they could benefit by waiting and South Vietnam’s now beginning to think they could benefit by waiting.” The warnings failed; FBI cables report more contacts between Chennault and Bui Diem.

Calling Republican Senate leader Everett Dirksen for the second time, Johnson implored him to intervene again with Nixon and his aides, and threatened to put the story “on the front pages” because it “would shock America.” Johnson emphasized: “They’re contacting a foreign power in the middle of a war. It’s a damn bad mistake.” He added:“They oughtn’t to be doing this. This is treason.”Dirksen responded simply,“I know.”

On November 4 Johnson learned from the FBI’s bugging that the Monitor’s seasoned Washington correspondent Saville Davis had visited Bui Diem to get a comment about“a story received from a correspondent in Saigon.” The FBI’s “eyes only” cable, relayed to Johnson at his ranch in Texas, reported Davis as having said that“the dispatch from Saigon contains elements of a major scandal which also involves the Vietnamese ambassador and which will affect presidential [candidate] Richard Nixon if the Monitor publishes it.” Unable to get Bui Diem either to confirm or to deny my scoop, Parry reports, Davis then visited the White House for comment and showed aides there my 38-word lead about the“purported political encouragement from the Nixon camp” to Thieu.

“The Christian Science Monitor’s inquiry gave President Johnson one more opportunity to bring to light the Nixon campaign gambit before Election Day,” Parry recounts. Before deciding what to do, Johnson consulted in a conference call with Rostow, Defense Secretary Clifford, and Secretary of State Dean Rusk.“Those three pillars of the Washington Establishment were unanimous in advising Johnson against going public, mostly out of fear that the scandalous information might reflect badly on the U.S. government,” Parry explains in summing up their extended answers. Johnson agreed with his advisers. An administration spokesman told Davis: “Obviously I’m not going to get into this kind of thing in any way, shape or form.” Based on these evasive responses to Davis, the Monitor decided against publishing my lead.

My lead gave Johnson a last-minute choice of remaining silent or going public with Nixon’s ploy on the eve of the election. The scoop also crystallized a unique split-screen moment: The most decisive period of the Vietnam War, settling the conditions for ending it, was moving in parallel with a most indecisive period in the American democratic process, the U.S. presidential election.

The White House joined the Monitor in keeping vital information secret from Americans about to cast their ballots for president while GIs and Vietnamese were dying in a faraway war. My incriminating lead provided a hinge-of-history moment—for the American election, the future of South Vietnam, and the thousands of Americans and Vietnamese dying and about to die in Southeast Asia as the war dragged on for four more bloody years. In what Parry describes in another context, my lead zeroing in on Nixon’s “treason” faded away into the United States’“lost history”—history that in this case would be written with more blood and tears.

Vice President Humphrey was also alerted by his chief speechwriter, Ted Van Dyk, that Thieu was going to hold off sending a delegation to the Paris peace talks, and that “in 1968 the old China Lobby is still alive.” Humphrey fumed, “I’ll be God-damned if the China Lobby can decide this government.” Yet that is what happened. Thieu’s explosive address made national headlines and cast doubts on Johnson’s ability to get the peace talks going and end the war. Nixon’s speechwriter,William Safire, voicing the sentiments of numerous pundits and a reputable polling firm, observed, “Nixon would probably not be president were it not for Thieu.”

After the election, [Pham Xuan] An and I gleaned a play-byplay of the final confrontations between Thieu and U.S. ambassador Ellsworth Bunker that revealed why the Vietnamese had backed out of going to Paris. A Vietnamese source close to the palace conversations shared with An and me his notes detailing what I described as “one of the most bizarre—if not scandalous—American diplomatic maneuvers in war-time history.”

In a nutshell the U.S. chief negotiator in Paris, Averell Harriman, made a proposal that Hanoi accepted on October 27 to begin peace negotiations starting November 6—the day after the presidential election—for a four-power conference that would give the National Liberation Front equal status and legitimacy with the Saigon government. In Saigon, however, Ambassador Bunker had secured Thieu’s agreement to go to a three-power conference, with separate delegations representing Hanoi, Saigon and Washington, but with the NLF sitting as part of North Vietnam’s delegation. “Here is Bunker getting Thieu’s agreement to a three-way peace conference in Paris,” a stunned diplomat told me. “But Harriman had already sold out Saigon by giving away to Hanoi the most important thing of all— representation of the National Liberation Front.”

On Nov. 5, 1968, by the narrowest of margins, Richard Nixon was elected president, winning by 499,704 votes, or 0.7 percent, over Hubert Humphrey. Upon his inauguration Nixon began a two-pronged policy of talking with the Communists in Paris and“Vietnamization”on the battlefield by withdrawing all U.S. troops. But Nixon also expanded the conflict into Laos and Cambodia, vowing in 1969,“I’m not going to be the first American President who loses a war.”Yet that is what he would become. He failed to end the war any better than Johnson’s attempt four years earlier, and he ushered in “the peace that never was.”

Originally published in the October 2013 issue of Vietnam. To subscribe, click here.