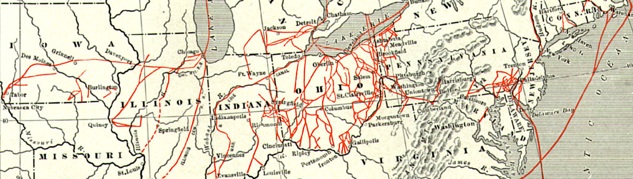

The Underground Railroad was the term used to describe a network of meeting places, secret routes, passageways and safehouses used by slaves in the U.S. to escape slave-holding states to northern states and Canada. Established in the early 1800s and aided by people involved in the Abolitionist Movement, the underground railroad helped thousands of slaves escape bondage. By one estimate, 100,000 slaves escaped from bondage in the South between 1810 and 1850. Aiding them in their flight was a system of safe houses and abolitionists determined to free as many slaves as possible, even though such actions violated state laws and the United States Constitution.

Facts, information and articles about the Underground Railroad

Established

Approximately 1780

Ended

Approximately 1862 with the start of The Civil War

Slaves Freed

Estimates run from 6,000

Prominent Figures

Harriet Tubman

William Still

Levi Coffin

John Fairfield

Related Reading:

How Canada Became the Last Stop on the Underground Railroad

The Legacy of Harriet Tubman: Freedom Fighter and Spy

The Beginnings Of the Underground Railroad

Even before the 1800s, a system to abet runaways seems to have existed. George Washington complained in 1786 that one of his runaway slaves was aided by “a society of Quakers, formed for such purposes.” Quakers, more correctly called the Religious Society of Friends, were among the earliest abolition groups. Their influence may have been part of the reason Pennsylvania, where many Quakers lived, was the first state to ban slavery.

Two Quakers, Levi Coffin and his wife Catherine, are believed to have aided over 3,000 slaves to escape over a period of years. For this reason, Levi is sometimes called the president of the Underground Railroad. The eight-room Indiana home they owned and used as a “station” before they moved to Cincinnati has been preserved and is now a National Historic Landmark in Fountain City near Ohio’s western boundary. Among the slaves who hid within it was “Eliza,” whose story formed the basis for the character of the same name in the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The Underground Railroad Gets Its Name

Owen Brown, father of the radical abolitionist John Brown, was active with the Underground Railroad in New York state. A story claims “Mammy Sally” marked the house Abraham Lincoln’s future wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, lived in while growing up was a safe house where fugitives could get meals, but the story is suspect.

The term Underground Railroad began to be used in the early 1830s. In keeping with that name for the system, homes and businesses that harbored runaways were known as “stations” or “depots” and were run by “stationmasters.” “Conductors” moved the fugitives from one station to the next. The Underground Railroad’s “stockholders” contributed money or goods. The latter sometimes included clothing so that fugitives traveling by boat or on actual trains wouldn’t give themselves away by wearing their worn work clothes. Once the fugitives reached safe havens—or at least relatively safe ones—in the far northern areas of the United States, they would be given assistance finding lodging and work. Many went on to Canada, where they could not legally be retrieved by their owners.

A trip on the Underground Railroad was fraught with danger. The slave or slaves had to make a getaway from their owners, usually by night. “Keep your eye on the North Star” was the watchword; by keeping that star ever in front of them, the runaways knew they were headed north.

Conductors On The Railroad

Sometimes a “conductor” pretending to be a slave would go to a plantation to guide the fugitives on their way. Among the best known “conductors” is Harriet Tubman, a former slave who returned to slave states 19 times and brought more than 300 slaves to freedom—using her shotgun to threaten death to any who lost heart and wanted to turn back.

Operators of the Underground Railroad faced their own dangers. If someone living in the North was convicted of helping fugitives to escape he or she could be fined hundreds or even thousands of dollars, a tremendous amount for the time; however, in areas where abolitionism was strong, the “secret” railroad operated quite openly. Stephen Myers of Upstate New York, a former slave, wrote in his own newspaper, Northern Star and Freemen’s Advocate, about his work helping other slaves escape. Myers became the most important leader of the Underground Railroad in the Albany area. “Vigilance committees” that formed within communities for the purpose of aiding runaways sometimes openly advertised their meetings. (In other eras of American history, the term “vigilance committee” often refers to citizens groups who took the law into their own hands, trying and lynching people accused of crimes, if no local authority existed or if they believed that authority was corrupt or insufficient.)

Being caught in a slave state while aiding runaways was much more dangerous than in the North; punishments included prison, whipping, or even hanging—assuming that the accused made it to court alive instead of perishing at the hands of an outraged mob. White men caught helping slaves to escape received harsher punishments than white women, but both could expect jail time at the very least. The harshest punishments—dozens of lashes with a whip, burning or hanging—were reserved for any blacks caught in the act of aiding fugitives.

The Civil War On The Horizon

Events such as the Missouri Compromise and the Dred Scott case drove more anti-slavery advocates to take active roles in helping to free slaves. A damper was thrown, however, when Southern states began seceding in December 1860, following the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. Even some outspoken abolitionist newspaper cautioned against giving the remaining Southern states reason to secede.

Lucy Bagbe (later Sara Lucy Bagby Johnson) is believed to be the last slave returned to bondage under the Fugitive Slave Law. She escaped from her owner near Wheeling in the Virginia panhandle (now the northern panhandle of West Virginia) and made her way to Cleveland in far northern Ohio, where abolitionists helped her secure lodging and employment as a domestic servant. When her owner tracked her down in December 1860, Cleveland’s abolitionists provided her a lawyer and tried unsuccessfully to buy her freedom but feared doing anything more to aid her at a time when the continued existence of the United States was threatened. Even the Cleveland Leader, a Republican publication that normally came down against slavery and the Fugitive Slave Law, cautioned its readers that letting the law take its course “may be oil poured upon the waters of our nation’s troubles.” Lucy was taken back to Ohio County, Virginia, and punished but was freed at some point after Union troops occupied the area. A Grand Jubilee in her honor was held in Cleveland on May 6, 1863.

The Reverse Underground Railroad

In Northern states bordering on the Ohio River, a “reverse Underground Railroad” sprang up. Black men and women, whether or not they had ever been slaves, were sometimes kidnapped in those states and hidden in homes, barns or other buildings until they could be taken into the South and sold as slaves.