[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t the end of the war, American technical teams fanned out across Germany in search of Nazi Wunderwaffen, or Wonder Weapons: guided missiles, jet aircraft, super-heavy tanks. Of most interest to the U.S. Navy was a submarine capable of operating submerged continuously for days on end—the Type XXI U-boat. Americans had known of its existence for nearly two years, after the British had passed along sketchy intelligence about a “fast submarine.” They knew even more in January 1945, when Allied forces captured plans for the U-boat at a steel plant in Strasbourg, France.

When Allied navy technicians finally got a good look at the real thing, its clean lines impressed them—the sleek hull and snorkel that retracted into the conning tower. They were impressed, too, that the Germans had designed and built this all-new submarine smack in the middle of the war, amid incessant enemy bombing raids. It was an audacious program, and the result—what the U.S. Navy called a “weapon of more advanced design than any heretofore developed”—had a profound impact. The impact, however, was not the one the Germans had hoped for.

THE NEED FOR AN ADVANCED U-BOAT grew out of Germany’s failed submarine strategy to destroy Allied shipping. Early in the war, German U-boat crews enjoyed tremendous success in slowing the flow of materiel from the United States to England, often sinking a half-million tons of shipping in a single month. They called it the “Happy Time.” Startled commanders in the U.S. and UK responded by reorganizing the convoy system and incorporating new technologies, including improved sonar and high-frequency direction finding on escort vessels.

In mid-1942, the Allies’ new antisubmarine warfare (ASW) campaign began pouncing unawares on U-boats at sea. At the end of 1942, merchant sinkings by German submarines took a manifest dive, while sinkings of U-boats rose proportionately—87 that year. The losses alarmed Vice Admiral Karl Dönitz, a veteran submariner and chief of the Kriegsmarine’s U-boat command. His workhorse subs, the Types VII and IX, were aging designs unsuited to the rigors of the new order in the North Atlantic. Dönitz decided he needed something altogether new; a stealthy boat that could evade enemy attacks. He placed his hopes in a radical departure from conventional submarine design—the “Walter Boat.”

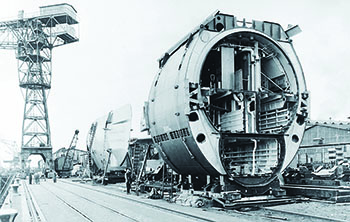

The concept was the brainchild of Hellmuth Walter, an exceptional German engineer, who first presented it to the Kriegsmarine in 1934. A standard U-boat electric-drive system used storage batteries to power motors when the sub was underwater, but battery capacity limited its speed and range. Walter reasoned that a submarine with a streamlined hull, driven by a hydrogen peroxide-fueled turbine, could power well past those limits. Heated hydrogen peroxide would generate steam, which would spin turbines connected directly to the propellers. The result would be much higher speeds and endurance that could be measured in days, not minutes.

Promising experimental versions were already in the works. During trials of prototype V-80 in 1940, the 72-foot sub hit speeds of 28 knots submerged—nearly four times faster than standard U-boats. In January 1942 the Kriegsmarine contracted the construction of four small Walter coastal patrol subs. Their keels were laid down that September.

Two months later, Dönitz invited Walter to a submarine conference in Paris. The admiral asked the professor how long it would take to build a full-size, ocean-going Walter Boat. Walter had disappointing news: the four small submarines were still months away from launching; a big U-boat would take years. But a pair of German navy construction experts in attendance saw a quicker way to build a more capable submarine.

Forget hydrogen peroxide, they told the admiral. Keep the streamlined form, use a conventional diesel and electric power plant, and fill the bottom hull with three times as many storage batteries as in standard U-boats, giving the new submarine a considerable increase in underwater endurance. In the opinion of the two experts, “While such a boat would not attain the underwater speed of the Walter Boat, it would certainly be capable of a speed far in excess of current types.” Walter suggested adding a snorkel—paired retractable tubes to provide air to the diesel engines and extract the exhaust fumes—which would allow the batteries to be recharged without having to surface the boat. That, and coating the snorkel with rubber to deflect radar waves would further enhance the sub’s stealthiness.

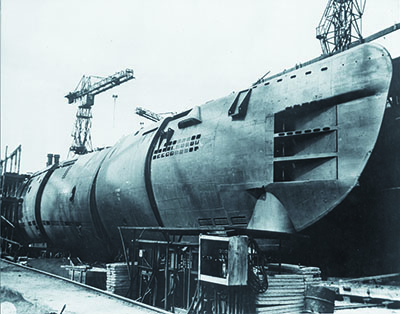

Naval engineers spent the next 18 months generating detailed blueprints for what would become the Type XXI Elektroboot—or “electric boat.” To eke out every gram of performance, they even subjected scale models to wind tunnel tests. On paper, the new warship looked like Karl Dönitz’s dream boat—the world’s first true submersible, a warship that could operate entirely beneath the sea. With its hydrodynamically smooth hull—bereft of deck guns, anchors, cleats, and other protuberances—and a huge battery array in the lower hold that provided current to a pair of powerful electric motors, the Type XXI Elektroboot would have a submerged speed of nearly 18 knots—a rate it could maintain for over 90 minutes. Using silent “creeper” motors, the boat could cruise beneath the surface at five knots for 60 hours. By contrast, the highest speed an American fleet submarine could run underwater was less than nine knots for about an hour.

When the admiral was satisfied with the design, he asked his Construction Branch how long it would take to get the Type XXI operational. “They envisaged the construction of two experimental boats,” he later wrote. Building the prototypes would take at least a year and a half, and debugging, a similar span. That meant serial manufacturing could not commence before late 1945. And that meant the new submarine would not be battle-ready before the end of 1946. “So long a time-lag was intolerable,” Dönitz said.

By early 1943 Britain and the United States had become so proficient at finding and sinking enemy submarines that they were setting records: in May 1943, they destroyed 45 U-boats—five on May 6 alone. The Kriegsmarine could not sustain such losses; its shipyards could replace only 26 submarines a month. In the Type XXI the admiral saw a weapon that could hold its own against the Allied campaign. But he needed dozens of them in service—yesterday.

So in June 1943 Dönitz approached Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments and War Production, to ask about alternatives. The ministry called for skipping the prototype phase and going straight to building war boats—a risky path. To further speed things up, the Type XXIs were to be built from eight prefabricated hull sections. American shipbuilders had employed that method with great success in the construction of simple vessels like Liberty ships and tankers. No one had ever tried the technique for building something as complex as a submarine. The sections, each weighing 70 to 165 tons, were to be manufactured at 32 different inland factories and barged to the yards for final assembly. The schedule, aimed at getting the first Type XXI in the hands of U-boat command by mid-1944, called for component work on each hull to be completed in four months, with a further two months on the slipways at Hamburg, Bremen, or Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland).

THE PLANTS MANUFACTURING the new boats’ sections had no experience in building entire modules, however. Even with technical assistance from the Kriegsmarine, the process did not go smoothly. Precision was paramount: because of the tremendous pressures underwater, it was imperative that the sections fit together perfectly with near-zero tolerances. But at the final assembly yards, workers discovered gaps of as much as three centimeters—over an inch. Some of the workmanship was downright shoddy—bad welds that could prove fatal during deep dives.

The first Type XXI, U-3501, was launched at Danzig on April 19, 1944, as a 55th birthday present for Adolf Hitler. The boat was not truly ready, but Speer and Dönitz wanted to impress the boss. As soon as the Führer’s entourage departed, workmen frantically moved in pontoons to keep the U-boat afloat until they could tow it to a dry dock. By the end of 1944, 64 Type XXIs had been commissioned—but that didn’t mean the U-boats were ready to sally forth. As each boat went through its trials, all sorts of defects showed up: in the engine superchargers, in the steering mechanism, in the advanced torpedo-loading system, in the snorkel. It may have taken only 180 days to build an Elektroboot, but it took another 120 days to repair all the deficiencies. It was a time-consuming effort when the Germans had no time to waste.

On March 16, 1945, U-2511 finally became the first Type XXI to deploy on a war patrol, steaming up the Kiel Canal toward Norway. The boat was skippered by Lieutenant Commander Adalbert Schnee, who over the course of 12 patrols in conventional U-boats had sunk or damaged 26 ships and was well decorated for his exploits: Iron Cross First Class and Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves. He was, in the eyes of Admiral Dönitz, “an exceptionally brilliant captain.”

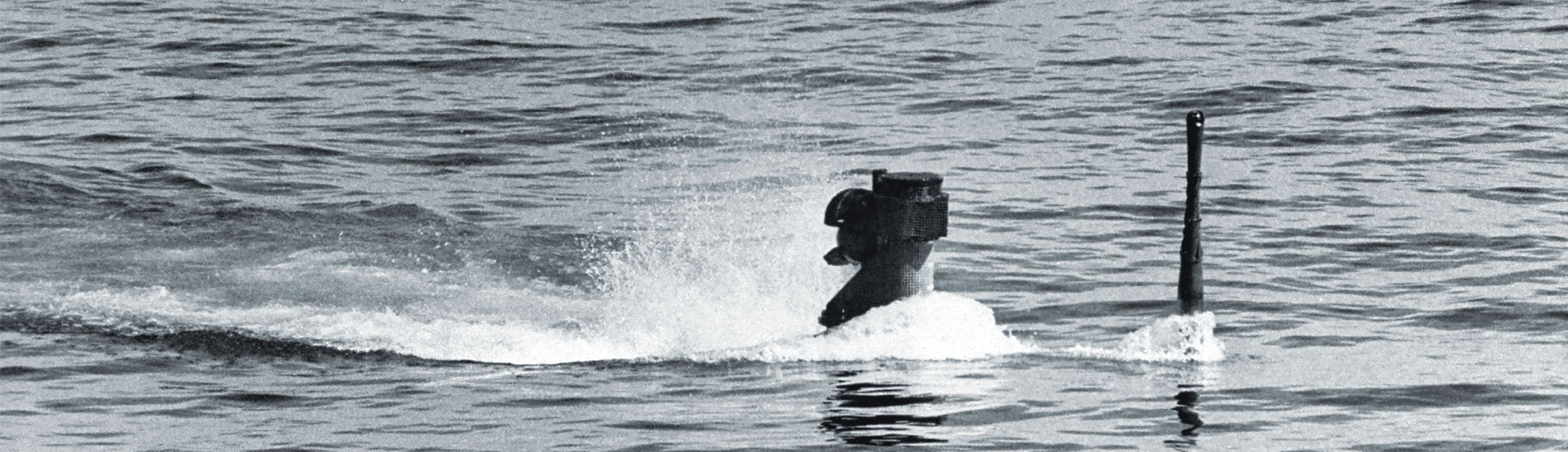

The boat suffered mechanical problems en route, and it was not until April 30 that U-2511 set out from Bergen, Norway, to battle the British. Two days later Schnee made contact with a Royal Navy ASW force. It detected him, but he escaped using his superior submerged speed.

On May 4 Schnee encountered another group, led by the 10,000-ton cruiser HMS Norfolk. He began stalking the enemy ships, using his U-boat’s super-sensitive passive sonar to successfully guide the sub beneath the destroyer screen and creep undetected to within 500 yards of the Norfolk. He raised his periscope barely above the sea’s surface for a peek. The image of the 632-foot warship loomed in the viewfinder. It was a perfect setup; the U-boat could not miss. Instead, Schnee broke off his approach, turned tail, and crept silently away.

The Norfolk was awfully lucky that day—and Schnee must have been frustrated. Just hours earlier the U-boat commander had received a radio message from Dönitz, by then Hitler’s successor as leader of the Third Reich, imposing an immediate cease-fire on all U-boats; the stalking was merely a practice run. Schnee returned to Bergen the next day to await the inevitable. On May 9 Adalbert Schnee surrendered U-2511 to the British. And that was that. After two and a half years of sturm und drang over the revolutionary submarine’s long gestation, the innovative Type XXI U-boat never saw combat and had no impact on the war.

BUT THE U-BOAT DID HAVE AN IMPACT.

In the final week of the war, the Kriegsmarine scuttled 81 Elektroboots. Eleven operational XXIs remained in Norway, with several more at German ports. Allied powers all clamored to take one home. They divvied up the best of the surviving boats: one to France, two to Britain, four to the Soviet Union, two to the United States.

In August 1945 U-3008 and U-2513 were transferred to the U.S. Navy. An American crew—assisted by a few German ex-Type XXI sailors to translate the labels on the dials, valves, switches, and knobs—sailed the pair to the sub base at New London, Connecticut, for technical evaluation. In April 1946 the navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey issued a 185-page report, “Former German Submarines,” that presented in nuts-and-bolts detail everything its initial investigating teams uncovered. The next phase was to see what the boats could do at sea, above and below the surface.

Like Adalbert Schnee, American commander Everett H. “Steiny” Steinmetz was a veteran submariner. A 1935 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, he led USS Crevalle on the successful July 1945 “Hellcats” mission to penetrate the Sea of Japan and devastate enemy shipping, awarding him his second Navy Cross (see “Vengeance is Mine,” November/December 2016). Steiny assumed command of the newly renamed USS Ex-U-3008 at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on July 24, 1946. His mission was to discover its true fighting capabilities.

The U-boat spent eight months at sea off the New England coast performing speed, diving, and snorkeling trials, and undergoing extensive sub-sea acoustics tests by the Underwater Sound Laboratory, a joint Harvard and Columbia University effort. “The boat’s sonar was wonderful,” Steiny recalled. “The creeping motors were truly silent. And the 3008 was real maneuverable submerged, but on the surface it was a dyed-in-the-wool stinker.”

In March 1947 Ex-U-3008 sailed from New London to Key West, Florida, to act as a target for the Fleet Sonar School. On its way south, the boat paid a visit to Norfolk, Virginia, to pit the Elektroboot against the ships of Task Force 67. Steiny’s adversaries had a devil of a time locating his U-boat when it was submerged. And even when he raised the snorkel, its rubber coating effectively deflected radar waves. “The air forces tried to pick us up, but couldn’t even find us on the surface,” he said, with a chuckle.

Ex-U-2513 went through similar tests and exercises. Among its crew was 19-year-old electrician’s mate Bill Tebo. Like Steiny, he was impressed with the sonar. “It was so much superior to the Americans’. We could pick up a ship at a hundred miles,” Tebo told an interviewer in 2004. “We operated with destroyers, destroyer escorts, blimps, and aircraft. They had so much trouble finding us, that at noontime we would sneak back into Key West and be drinking beer on the beach while the surface ships were out there looking for us.”

The highlight of Tebo’s time on the former U-boat was a day trip with President Harry S. Truman. On November 21, 1946, the president boarded the submarine for a four-hour cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. After breakfast, the skipper, Lieutenant Commander James B. Casler, dived the boat to 440 feet. “Marvelous,” said Truman afterward. As he disembarked, 2513’s crew presented their commander in chief with a “Royal Order of Deep Dunking” certificate.

But it wasn’t always beer and celebrities. The worst moment for Tebo came during a deep-diving test. German specifications cited a maximum of 1,100 feet but “at around 750 feet we cracked the hull in the torpedo room,” he recalled. “We did it twice.” The experience so unnerved Tebo he began to wonder if he had made the right choice by entering the silent service. The navy retired Steiny’s Ex-U-3008 in June 1948; it deemed Ex-U-2513 unsafe a year later and retired it in July.

BY THAT TIME THOUGH, the U-boat had had a powerful influence on submarine design in the United States.

When the navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey issued its 1946 report on the sub, their conclusions were clear: “The results obtained indicate the need to exploit the possibilities of the type to the maximum.” Just six months later, the U.S. Navy embarked upon a program to modify its newer fleet submarines. They called it the Greater Underwater Propulsion Power Program, or “GUPPY.” They decluttered their original subs’ hull shape, swapped the clunky conning tower for a sleek “sail,” installed an American-designed snorkel, and nearly doubled the size of the battery. This gave the rebuilds a 16- to 18-knot submerged speed for 30 minutes—slower and shorter than a genuine Elektroboot, but a marked improvement over the American subs’ wartime performance. Between 1946 and 1960, the navy converted a total of 52 fleet subs to GUPPYs.

To hedge its bets, in 1949 the navy also launched a parallel program for a new keel-up design based directly on the Type XXI. The specifications for the six Tang-class submarines were very close to the Elektroboots’: a fully streamlined 269-foot hull; 1,600 tons displacement; and underwater speed of 17.4 knots.

The other Allied nations borrowed similarly from Type XXIs. The British entry in the postwar submarine race, the Porpoise-class, combined Type XXI and GUPPY features to produce boats capable of 17 knots submerged. They also built a pair of 25-knot experimental subs that would have made Hellmuth Walter proud: HMS Explorer and Excalibur were fueled by hydrogen peroxide. The French Narval and the Soviet Whiskey-class submarines were also based on XXI technologies. All these boats served until the early 1990s.

In the United States, the XXI’s influence waned in the early 1950s, when the navy made a breakthrough in hydrodynamic hull forms—the “teardrop” shape, a fully rounded hull that tapers at the stern. The USS Albacore, commissioned in 1953, set a record of 33 knots submerged; its hull was the prototype for most of today’s conventional and nuclear submarines.

THE TYPE XXI’s technological superiority, though, inspires looks to the past even more than to the future. For seven decades armchair admirals have debated the question, “Would the outcome of the war have been different with the new U-boats?”

German naval historian Siegfried Breyer’s answer is, simply, “No.” He asserts that flotillas of stealthy Elektroboots might have breathed new life into the Battle of the Atlantic, perhaps begetting another Happy Time: “The new U-boats would once again have been capable of attacking convoys and sinking ships successfully.” He believes that the Allies’ ASW tactics would have failed against the XXIs, opening the way for Germany to “cut down the tremendous stream of war materials of all kinds across the Atlantic, if not to halt it altogether.” But, writes Breyer, the advantage would have been temporary. “The new U-boats could only have prolonged the war one or more years, for a decisive turnaround was no longer possible [after] the middle of 1943.”

Tied up at a pier in Bremerhaven, Germany, is the only surviving Type XXI, the Wilhelm Bauer. Even today, the sleek streamlining that caught the fancy of U.S. Navy technicians back in 1945 is readily apparent, as is its menacing beauty. The Type XXI Elektroboot never became the Wunderwaffe the Kriegsmarine had hoped it would, but Walter’s design embodied a revolutionary new vision of what a true submersible warship could be.✯