It wasn’t until February 23, 1945, that the Turkish Grand National Assembly voted—unanimously—to declare war on Germany and Japan. This was only six weeks after Turkey severed links with Japan, six months since ending diplomatic relations with longtime trading partner Germany, and less than three months before the German surrender. The declaration of war was mostly a formality to join the postwar United Nations—Turkey would remain a non-belligerent—but it was still an unexpected act from a country that for years had stubbornly refused to be drawn into choosing a side in the war. In the words of one Turkish minister, Turkey “was determined to maintain her neutrality to the end.” While the rights of neutrals were rarely respected by the warring countries, Turkey had dug in its heels.

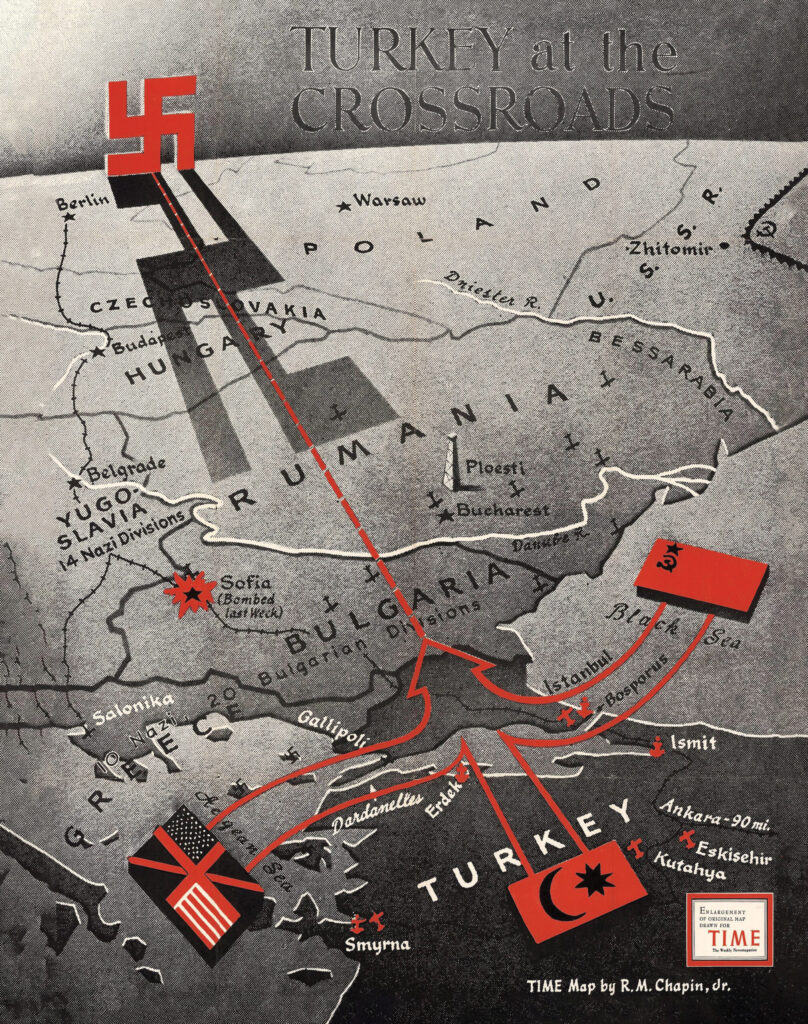

It was a fine and dangerous line on which Turkey balanced. The country was terrified by the threat of Luftwaffe bombers in occupied Greece, which could level Turkish cities overnight. But Turkey feared a victorious Soviet Union even more than a victorious Germany, as the Soviets had been eyeing Turkish ports and waterways for years. This animosity was nothing new: beginning in 1568 Turkey and Russia had fought 17 wars, the majority of which resulted in Russian victories. As Ottavio De Peppo, the Italian ambassador to Turkey during the war, phrased it, “the Turkish idea is that the last German soldier should fall upon the last Russian corpse.”

Beginning in 1939, war had consumed the region around Turkey, the nation that served as the literal bridge between Europe and Asia. Along with Nazi-occupied Greece directly to the west, the Germans also controlled the former Ottoman Balkan territories of Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Serbia to the northwest. Turkey’s southern neighbors, the British and French colonial empires occupying Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, had quickly been drafted into battle for the Allies and, after 1941, Turkey’s longtime enemy, the Soviet Union, joined the fight against Germany—meaning Turkey had become encircled by belligerents. Yet Turkey, with crucial shipping routes connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and possessing the major land passage to the oil-rich Caucasus, maintained its neutrality and independence throughout nearly all of World War II. This was not evidence of indecision or cowardice, but rather a sign of a carefully tended strategy—one created, as Turkey saw it, out of pure necessity. And one that allowed it to preserve its economy as well as avoid the physical ravages of battle.

Neutrality had been a cornerstone of the Republic of Turkey since it had been created in 1923 by founding father and president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the soldier-turned-leader-turned-national hero. Atatürk had built his country from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, the 600-year Islamic imperial realm that had once ruled much of the Middle East, but which in its last decades had been reduced to a puppet state for more powerful European nations. After the Ottoman defeat in World War I, Atatürk’s forces fought off the French and British as well as Turkey’s millennium-old enemies of Greece and Armenia in the 1919-1923 Turkish War of Independence. Atatürk’s subsequent reforms transformed Turkey into a secular, modern nation, putting the new country on the path to peace and prosperity. Atatürk believed the young republic needed to look inward to develop fully, coining the phrase “Peace at home, peace in the world” to explain the new isolationist policies he advanced. But this position had become increasingly untenable as fascist governments began forming across Europe, inching ever closer to Turkey’s borders.

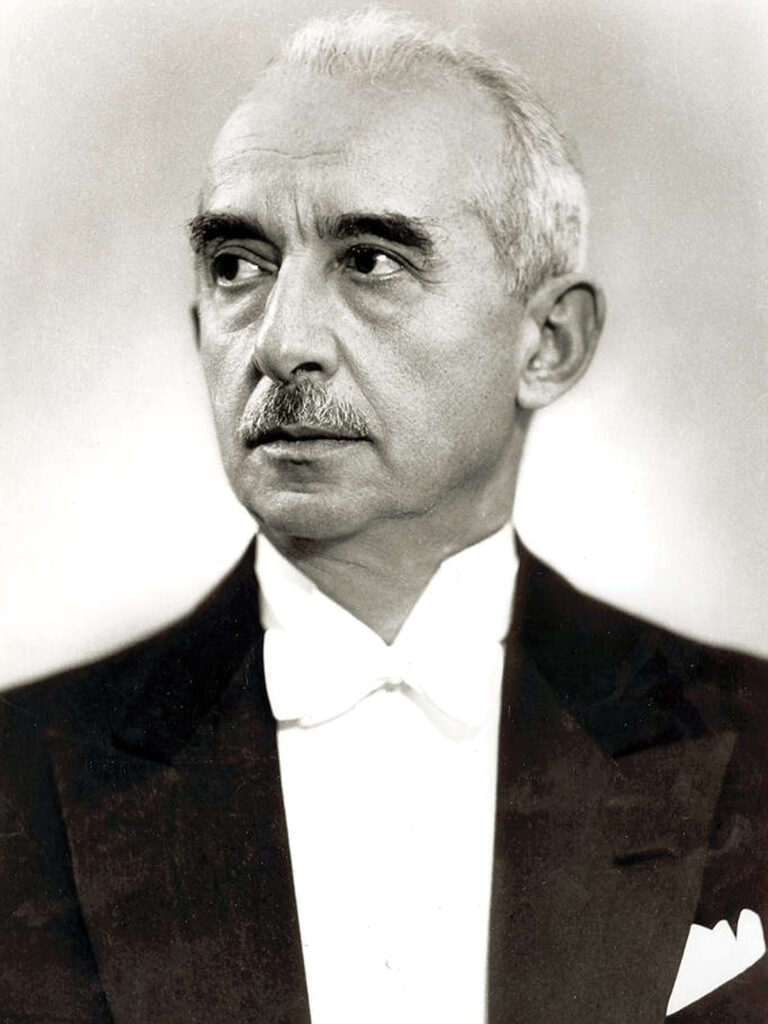

Atatürk died of cirrhosis of the liver on the morning of November 10, 1938, only hours after Nazis had shattered the windows of Jewish businesses and synagogues across Germany and Austria on Kristallnacht. The two stories dominated the evening editions of newspapers around the world. Atatürk’s successor, the unassuming İsmet İnönü, had been the equivalent of a colonel during World War I, fighting on the Caucasus and Palestinian fronts, where he became Atatürk’s confidante. He later rose to the equivalent of brigadier general during the Turkish War of Independence, winning two major battles against the Greeks and serving as commander at the final Turkish victory in 1922.

Slim and shy in contrast to the charismatic and forceful Atatürk, 54-year-old İnönü was committed to continuing Atatürk’s policy of international neutrality, even once World War II began. İnönü believed neutrality was about more than just preserving economic and political relations with the Axis and the Allies; he saw it as a matter of survival for his young country, necessary to avoid takeover by its larger and more established neighbors like Italy, Germany, or—worst of all—the Soviet Union.

İnönü’s view was part of a larger cultural stance, explains Murat Önsoy, a professor in War Studies and German Studies at Turkey’s Hacettepe University: “Turkish elites came from a generation that had witnessed the destruction of the Ottoman Empire…. They had seen how the Balkans had faded away out of their hands and how Turkey had been slighted in World War I, and they witnessed how hard the Republic was achieved.”

Even though the country had signed the Tripartite Alliance treaty in October 1939 with France and Britain, a 15-year agreement of collaboration in the interests of national security, İnönü officially declared Turkey’s non-belligerence on June 26, 1940. This was a tough blow for the British. Prime Minister Winston Churchill complained that Turkey was “shirking her responsibilities.”

While the British would still have access to Turkey’s strategic shipping ports, they were more interested in seeing Germany lose such rights, knowing the loss would hit Germany harder, since after its defeat in World War I it had no colonies and few trading partners. Churchill also wanted a base in the area from which to launch his desired Mediterranean attacks on what he called Europe’s “soft underbelly.” But as the war advanced, the Allies believed that, if they were patient, Turkey would join their side soon enough. The British ambassador to Turkey, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, recommended “keeping the pot boiling”—meaning that Allied leaders should continue their pressure campaign on the Turks.

In late September 1939, the German ambassador to Turkey, Franz von Papen, had stated that “in no circumstances did Germany intend to start a war in the Mediterranean.” But rival Italy entered the war in June 1940, and Germany had completed its takeover of both Greece and the Balkans by 1941. Hitler immediately sent an official letter to İnönü confirming German respect of Turkish neutrality, declaring that he did not start the war, that he was not “intending to attack Turkey,” and that he had “ordered troops in Bulgaria to stay far from the Turkish border in order not to make out a false impression of their presence.”

Turkey initially looked the other way as both Germany and Britain infringed its neutrality. The Turkish government chose a very loose interpretation of its agreement at the 1936 Montreux Convention, which confirmed Turkey’s control over the Turkish Straits—the Bosphorus and Dardanelles waterways—but also required the country to prohibit the passage of belligerent naval ships in any conflict in which Turkey was neutral. Yet Allied and Axis warships were regular presences in both during the war.

There were many reasons why Germany didn’t simply invade Turkey. Even though several foreign diplomats estimated that it would only take them 48 hours to conquer Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city, the ghost of Gallipoli—when Ottoman forces had fought off the better-supplied British, Australian, and New Zealand militaries for eight months in World War I—still haunted the memories of the European powers, and the Germans kept their distance. In addition, Turkey was larger than all European countries except the Soviet Union, with a difficult terrain and a sizeable—though unmodernized and undersupplied—standing military, making quick and easy victory anything

but certain.

But Germany’s primary reason for hesitating to invade Turkey was economic. Throughout the 1930s, more than half of Turkey’s trade was with Nazi Germany. German banks had also taken advantage of the high prices in the Turkish precious metals market to sell their looted gold. Deutsche Bank ledgers recovered by the Allies after the war showed that more than 2,200 pounds of gold stolen from German’s Holocaust victims had been sold to Turkey.

İnönü understood early that none of the Allies could replace Germany as a primary trading partner. Britain, France, and the United States had their own sources for the country’s cotton and tobacco, in contrast to the Germans, whose lack of colonies limited their access to such products. In return, Germany remained the most ardent supporter of Turkish neutrality since a neutral Turkey was a guarantee of a ready supply of raw materials.

The most important raw material that Turkey supplied was chromium. This was manufactured into chrome, an essential material for making stainless steel since it provides resistance to rust, and was used to make gun barrels, tanks, aircraft engines, ball bearings, shells, and submarine parts. In 1939, Turkish chrome output was about 200,000 tons per year, about a fifth of the world’s total, of which Germany bought half. This was the only non-Allied source of quality chrome. There were some mines in Greece and the Balkans, but the deposits didn’t have the more preferred chromium-to-iron ratio of Turkish chrome.

The British were keeping a close eye on all this. British ambassador to Turkey Knatchbull-Hugessen sent a report in 1941 to the Ministry of Economic Warfare noting that “Chrome ore is very high on the list of commodities which were believed to be of critical importance to Germany.” He estimated that “stocks are believed to be equivalent to about seven months’ supply.”

He hadn’t exaggerated. Albert Speer, Germany’s Minister of Armaments and War Production, wrote in a memorandum to Hitler on November 10, 1943, that “should supplies from Turkey be cut off, the stockpile of chromium is sufficient for only five to six months…almost the entire gamut of artillery would have to cease from one to three months after this deadline.” Germany also understood that if it invaded Turkey, the Turks would quickly destroy the mines, as the Greeks had done in their country.

Fully aware of this dynamic, the Allies remained less concerned about Turkey’s declared neutrality than with its material boost to the German war machine. But İnönü was elusive with the Allies when pressured on the topic and sidestepped both British and American proposals to cease exports to Germany, though Turkish diplomats promised that they were employing various subterfuge to delay shipments.

The British kept up diplomatic pressure, but Turkey became more and more distant as Germany consolidated its power around the Mediterranean. Turkey and Germany signed a 10-year mutual non-aggression pact on June 18, 1941, just four days before Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union.

But, at the same time, as the full extent of the damage from France’s collapse the year before became apparent and alongside new threats to Britain’s Middle Eastern colonies, Turkey’s value to the Allies increased. And the country had plenty of concerns about the goals of the Axis Powers. While Turkey had a historically close relationship with Germany, the same could not be said for the Axis power of Italy. Mussolini’s cries of “mare nostrum,” or “our sea”—a term popular with Italian fascists to encourage domination of the Mediterranean Sea—combined with Italy’s construction of military bases on the Italian-controlled Dodecanese Islands only miles off Turkey’s southwest shore, had always made İnönü hesitant to join the Axis, as well as grateful for the British naval presence in the area. As the war completed its third year, it seemed Turkey’s resolve to remain a non-belligerent was finally beginning to waver.

In late January 1943, Churchill and İnönü met in a Turkish railcar for the Adana Conference, where Churchill yet again tried and failed to convince İnönü to join the Allies. The details of the 90-minute discussion weren’t recorded, but rumor has it that at one point an exasperated Churchill asked how the Turks couldn’t hear the German guns right over their border. İnönü reportedly in-formed Churchill that, since he had been a gunner in his earlier military days, he couldn’t hear very well.

Önsoy, the Turkish professor in War Studies, calls this İnönü’s “wait and see mentality.” This attitude led one of the participants at the Second Cairo Conference, attended by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Churchill, and İnönü in December 1943, to remark that the Turkish delegation “wore hearing devices so perfectly tuned to one another that they all went out of order at the same instant whenever there were mentions of the possibility of Turkey entering the war.”

İnönü would remind his cabinet of the Turkish proverb, “There is always safety in patience.” By the end of 1943, though, İnönü’s patience was becoming a source of danger. The Germans openly threatened to bomb Turkish cities if the country abandoned its neutrality to join the Allies. German ambassador von Papen calculated that since the majority of Istanbul was composed of wooden structures, one air raid by the Bulgaria-based Luftwaffe could easily have the entire city up in flames.

Yet İnönü also knew that if he did not declare war against Germany, he would have no say in the postwar plans already being negotiated among the Allies. Relations with Britain had deteriorated as Britain tired of the Turkish delegation’s stalling tactics. Even the ever hopeful and tenacious Churchill wrote in his journal that he was “becoming resigned to Turkish neutrality.”

At dinner with Roosevelt and Stalin during the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Churchill suggested that a country as large as the Soviet Union “deserved access to warm water ports.” Joseph Stalin was less subtle, announcing, “We ought to take [Turkey] by the scruff of the neck if necessary.” Churchill had earlier warned İnönü that he would not stop the Soviets from taking control of the Dardanelles waterway if Turkey refused to join the Allies. Such statements confirmed Turkey’s worst fears about postwar realignments.

İnönü took note of Germany’s losses on nearly every front by that next spring, particularly at Stalingrad. In April 1944, Britain and the United States threatened Turkey with an embargo unless Turkey stopped sending strategic materials, most notably chrome, to Germany. Turkey ceased all shipments on April 21. Churchill told the British Parliament that Turkey had provided “good service” by halting chrome exports, despite what he characterized as the country’s “exaggerated attitude of caution.”

Turkey officially declared war in February 1945. Never as liberal-minded as his predecessor, İnönü used this as an excuse to crack down on dissidents and exert further control over the country’s media. The once commonplace pro-German editorials disappeared from the pages of all major Turkish newspapers.

The war declaration didn’t involve any active fighting on the part of Turkey or its large military and there were no casualties. However, the American ambassador to Turkey, Edwin C. Wilson, noted that the Turks “expect treatment identical to that which has been given to the other United Nations which have not been occupied by the enemy and they do not consider themselves in the same category as neutrals.”

Turkey’s strategic importance, once its greatest vulnerability, now became its strength, as its location was integral to the emerging Western focus on containing the USSR. The Soviet threat came at the right time for Turkey, dissipating any Allied resentment over its previous neutrality. Roosevelt said he did not blame the Turkish leaders for not wanting to get caught “with their pants down.” Great Britain quickly forgot any grudge it might have held, as the two countries stood together against Soviet expansionism.

President Harry Truman announced in his Truman Doctrine in 1947 that any attack on Turkey would be an attack on the United States, and he signed an aid agreement with Turkey worth $150 million. Five years later, Turkey was made a full member state of NATO, the only Muslim-majority country to do so until Albania joined in 2009.

While İnönü does not carry the mystique or fame of his predecessor Atatürk, his calculating negotiations ensured his country avoided seizure by the Soviets, either through invasion or as war reparations for having aligned themselves commercially with the losing Axis. And Turkey didn’t have to rebuild itself physically or economically like so many of its European neighbors in the aftermath of the war.

İnönü later defended his country’s initial adoption of neutrality by asking, “With what right could anyone expect us to do anything else at the time, when the Germans were at the gates of Istanbul, Britain feared invasion of the British Isles, Russia had a Non-Aggression Pact with Germany, and the United States was not in the war?”

The middle course—that Atatürk had originally envisioned and İnönü had maintained—allowed the country uninterrupted development and modernization while simultaneously preserving its independence. There hadn’t been peace in the world, but İnönü had managed some semblance of peace at home, achieving his stated goal to be “at the table but not on the menu.”