After the inconclusive Union victory at Stones River in January 1863, Union Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland occupied and fortified Murfreesboro, Tenn., and waited. And waited. Meanwhile, Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee retreated 30 miles south to a line centered on Tullahoma, Tenn., and screened by a series of rocky hills. Convinced that Rosecrans’s next move would be to attack the important rail junction at Chattanooga, 55 miles to the southeast, Bragg spread his forces out to block the only roads through the hills, which ran through a series of passes from Shelbyville in the west to Beech Grove in the east. Fearing that Bragg would move to reinforce the Rebel army defending Vicksburg, Mississippi, Union General in Chief Henry Halleck pressured Rosecrans to do something—anything. In late June 1863, the Union commander

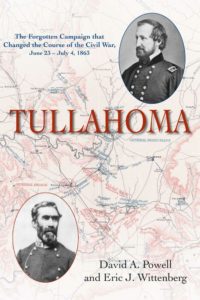

By David A. Powell and Eric J. Wittenberg

Savas Beatie, 2020, $34.95

finally moved, orchestrating an 11-day campaign that forced Bragg to abandon strategically vital Middle Tennessee. It was a turning point in the Civil War, but involved remarkably few casualties and has been overshadowed by the simultaneous Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. When Secretary of War Edwin Stanton belittled Rosecrans’ achievement in comparison to Grant’s, Rosecrans replied, “I beg on behalf of this army that the War Department may not overlook so great an event because it is not written in letters of blood.” A new opus by David A. Powell and Eric J. Wittenberg, Tullahoma: The Forgotten Campaign That Changed the Course of the Civil War, June 23-July 4, 1863 (Savas Beatie, $34.95) provides a welcome, thorough examination of Rosecrans’ singular success that summer. The two veteran authors spoke recently to America’s Civil War.

ACW: Explain why Tullahoma is considered a brilliant campaign that prompted Lincoln to write to secretary John Hay, “the flanking of Bragg at Shelbyville, Tullahoma and Chattanooga is the most splendid piece of strategy I know of.”

EW: Rosecrans designed and implemented an absolutely magnificent campaign of maneuver and deception that left Bragg completely befuddled. With minimal bloodshed, Rosecrans maneuvered Bragg out of all of Tennessee other than Chattanooga.

DP: Rosecrans faced some difficult terrain challenges in Middle Tennessee. Both the Elk and Duck Rivers lay across his front, providing defensive advantages to Bragg; plus, there were the hills of the Highland Rim, which likewise created defensible chokepoints. Rosecrans’s decision to conduct a turning movement in such difficult terrain was both ambitious and risky, but it paid off handsomely.

ACW: Soldiers joked that the word “Tullahoma” was derived from the Latin for “mud” and “more mud.” How did inclement weather and terrain affect the campaign?

EW: It rained pretty much the entire campaign, which turned roads into quagmires. Further, the ground in that part of Tennessee tends to be very spongy, making movement all the more difficult. That Rosecrans accomplished what he did set against the backdrop of those terrible

weather conditions is all the more remarkable.

DP: That rain was even more troublesome because it came so unexpectedly. Overall, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi were in drought that summer, with the rivers running below normal and the rain coming infrequently. Both the month just before the campaign began, and the thirty days just after the campaign concluded, saw very limited rain. So contrary to experience, sustained and heavy rains almost daily while the campaign was under way surprised and frustrated for the commanders and men alike.

ACW: Cavalry and mounted infantry played a vital role in the campaign, notably the heroic stand by Union Col. John T. Wilder’s mounted infantry “Lightning Brigade” at strategically located Hoover’s Gap. Why were horse soldiers so important and what, in general, were the principal strengths and weaknesses of both sides’ mounted units?

EW: Wilder’s command was, as you say, mounted infantry, not cavalry. The men used their horses as fast transportation, but they fought using infantry tactics and infantry weapons, particularly their long-barreled Spencer rifles. That said, unlike the Eastern Theater of the war, where the areas being contested by the two armies were compact, the Western Theater had huge areas of conflict and of responsibility. These fronts were just too long to be managed by foot soldiers. Cavalry was necessary to provide the speed of movement and the flexibility to cover large areas of land.

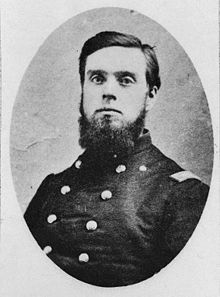

DP: Mobile forces, both cavalry and mounted infantry, played a significant role in 1862, and were no less vital in 1863. The Confederates especially invested large resources, both men and horses, in their mounted arm. Proportionately, despite its smaller size, the Army of Tennessee had nearly twice the amount of cavalry that normally accompanied Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Unfortunately for Bragg, his cavalry leaders were not always capable of handling these large forces effectively, and collectively, Maj. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, Maj. Gen. Joseoph Wheeler, and even Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest let Bragg down during the campaign.

ACW: On June 21, Morgan’s cavalry set off on a famous raid across the Ohio River. What was Morgan’s intention, and how did his plan affect the outcome of the Tullahoma campaign?

EW: It’s important to note that Morgan disobeyed his orders. He was supposed to move into Kentucky in the hope of drawing off Union forces but instead he went off on a fruitless and unsuccessful raid that wrecked a good division of cavalry and left Bragg without sufficient cavalry to detect the movements of Rosecrans’ army. Morgan’s absence gave Rosecrans a significant advantage–—the element of surprise.

DP: Morgan’s decision to ignore Bragg’s orders is the most egregious example of that leadership failure referenced above, and his absence hurt Bragg badly. Not only did Morgan’s departure strip Bragg’s vulnerable flank and preclude an early warning of Rosecrans’s movements, but also, when Bragg tried to redirect Morgan from Kentucky to strike at Rosecrans’s rear during the first few days of the campaign, Morgan ignored that directive as well.

ACW: Explain the importance of new weapons in the campaign—British Whitworth sharpshooter rifles for the Southerners and Spencer repeating rifles for the bluecoats.

EW: One of the most fascinating aspects of the Civil War for me has always been the relationship between the evolution of tactics as driven by advances in technology. Wilder’s mounted command, armed as it was with Spencer repeating rifles, became a real prototype for modern armored units. The Spencer was, in tactical terms, a force multiplier. The Whitworth rifles had a similar effect. Because they had an extended range and could be loaded while lying prone, they made it easier for Confederate sharpshooters to pick off artillery crews.

DP: To the above I would add one of the more fascinating possibilities of the war—Rosecrans’ desire to create a number of “Elite Battalions” within the Army of the Cumberland, drawn from the soldiers who distinguished themselves under fire at Stones River, mounted and armed with either Henry or Spencer repeating rifles. The battalions, had the government let Rosecrans pursue his idea, might have created a much larger force of “Lightning Brigades.”

ACW: Talk about how the discord and infighting among Bragg and his corps commanders, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, Lt. Gen. William Hardee, and Wheeler (cavalry) negatively affected the Confederates’ fortunes in the last days of June.

EW: I’ve never seen another army with the degree of dysfunction of the Army of Tennessee. Everyone seemed to be scheming, particularly aimed at effecting the removal of Bragg as commander. Loyalty became a major measure of an officer’s qualifications for high command, with the most notable example being Joe Wheeler. Wheeler was not competent to command a corps, but he was a Bragg loyalist and he was rewarded for that.

DP: By the time of the Tullahoma campaign, Bragg and his senior corps commander, Leonidas Polk, barely spoke to each other, and never about military matters. Neither man respected the other’s martial abilities. Hardee had also lost faith in Bragg. In fact, Davis had actually ordered Bragg relieved of command that spring, a decision that if carried out might have helped heal the rifts within the army, but Gen. Joseph E. Johnston wanted no part of the responsibility taking command would entail and so he refused to execute that order. It is little wonder that the Army of Tennessee failed so spectacularly that summer.

ACW: Rosecrans gave off pursuing the Confederates after they abandoned Tullahoma. Why?

EW: On June 30, 1863, Bragg faced the inevitable, falling back behind the Elk River. Rosecrans could have pursued him all the way to Chattanooga but elected not to do so primarily because the Army of the Cumberland had accomplished the campaign’s goal, which was to liberate Middle Tennessee. Further, Rosecrans had outstripped his ability to supply his army effectively from his base in Nashville. As it was, the Tullahoma Campaign was a masterpiece of logistics.

DP: Lacking any other means of supply – namely, a waterborne line of communications, Rosecrans had no choice but to pause and put his rail lines in order.

ACW: Why did Rosecrans have a breakdown at Chickamauga and what was the result?

EW: I tend to be a Rosecrans supporter, as I think he was the strategic genius of the war. He was extremely high strung by nature, and I think that the stress finally caught up to him. While Chickamauga was clearly a tactical defeat for the Army of the Cumberland, I think that Rosecrans managed the army well enough that Chickamauga was not the crushing blow to his army that it could have been.

DP: After the war, David Stanley, who served as Rosecrans’ chief of cavalry, noted that while on campaign Rosecrans became very overwrought. He rarely if ever slept, and instead survived on cigars and coffee. Stanley thought that Rosecrans’ constitution could stand the strain for a week or two, which was the duration of the Tullahoma Campaign. He couldn’t go a month, however, without suffering at least some temporary decline in his faculties—about the length of the Chickamauga campaign. Rosecrans’s unwillingness to delegate, and his tendency to micromanage every detail simply broke him down.

ACW: Rosecrans believed his Tullahoma victory was on par with Meade’s at Gettysburg and almost as critical as Grant’s at Vicksburg. Why is Tullahoma a forgotten campaign?

EW: Tullahoma ends up being the red-headed stepchild to Gettysburg and Vicksburg for a variety of reasons. The butcher’s bill at Gettysburg was staggering, while Rosecrans won a campaign of maneuver without a major engagement. Tullahoma also lacked the drama of Pickett’s Charge or the unconditional surrender of an entire army at Vicksburg. Lacking a marquee battle, lacking tons of casualties, lacking fascinating figures such as Lee and Grant, it seems that Tullahoma was destined to be overlooked. We wanted to rectify the fact that this brilliant campaign has been forgotten, and we hope we have done so.

DP: Eloquently put. The spotlight was focused on Mississippi and Pennsylvania, which provided both more drama and more pathos. Few civilians understood that clearing Middle Tennessee of the Confederates was a critical step on the road to Chattanooga, and eventually, Atlanta.

This interview appeared in the March 2021 issue of America’s Civil War.