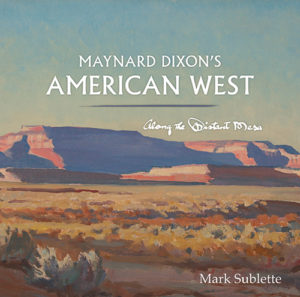

Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona, feels more like a museum of Western art and history, while the gallery’s website strives to reach fans of both traditional and contemporary Western and American Indian art. The man who keeps it all running is gallery founder and owner Dr. Mark Sublette. When he’s not buying, selling or researching art, Sublette is either writing (he’s the author of the Charles Bloom murder mystery series and the recent biography Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along the Distant Mesa) or hosting the Art Dealer Diaries podcast. The former physician recently spoke with Wild West about his interest in Western art and history and painter Dixon.

What sparked your interest in Maynard Dixon?

What sparked your interest in Maynard Dixon?

I’ve threatened to write a significant book on Maynard Dixon for a dozen years, and, as with many authors, I needed a deadline. Co-curating the upcoming Maynard Dixon exhibit [through Aug. 2, 2020] at Scottsdale’s Museum of the West was the catalyst required to finish an overdue manuscript.

Does Frederic Remington deserve a measure of credit for Dixon’s success?

Remington indeed set Dixon on his path at age 16 when the famous artist took time to review Dixon’s sketches. His encouragement to follow one’s course as a painter, and giving sage advice—while you might not get rich, it’s an honest living, and one that can make you happy—resonated with the precocious artist.

What was Dixon’s relationship with Charles Lummis like?

Dixon’s father died when Maynard was 18, and [Los Angeles journalist and Indian activist] Charles Lummis stepped in and filled that role shortly after that. Lummis was a champion of Dixon’s abilities, encouraging him to go east to see the West. When Dixon went through a mental breakdown after his first marriage failed during the end of World War I, Lummis helped Dixon to stay on the artistic path, getting him back to work. Dixon took his words and actions seriously, but those could cut both ways. Maynard was one of Lummis’ pallbearers in 1928, along with [landscape painters] Edgar Payne and William Wendt and [actor] Douglas Fairbanks.

What were Dixon’s little-known ties to San Francisco’s famed Golden Gate Bridge?

Joseph Strauss, the head engineer of the Golden Gate Bridge project, asked Dixon to help find a bridge architect. Dixon offered up young architect Irving Foster Morrow, whom Strauss hired. Through the Morrow relationship Dixon received an offer to do the initial drawings of the Golden Gate Bridge, along with paintings to be rendered for the $35 million bond initiative, which ran in the San Francisco Chronicle on Oct. 1, 1930, and passed that same year in November. Dixon recommended the bridge color remain international orange—the color of the underpainting. The bridge supervisors were more interested in black, gray and white colors. Dixon wrote to Morrow, “The board should not try to be smarter than God!” The bridge was kept international orange.

Doctor to gallery owner to historian to novelist. Explain that path.

My parents were research scientists and writers, so it was a natural lane for me to find a career in medicine, one I enjoyed immensely. Unfortunately, my true love emerged along the path, that of an art collector, who soon went overboard. I realized that if I sold art, I could have a more extensive collection. I tell people who ask, “Medicine was my first serious girlfriend; art was my wife.” I don’t think you can have a genuine appreciation of art without an understanding of history—this is the building block of art I crave. My other love is fiction writing. I’m a storyteller with a physician’s background and an appreciation of art. Writing a murder mystery series based on the art world seemed a natural.

Which interests you more, Western art or history?

Yes, is the answer! I literally cannot separate the two. History is a large dollop of ice cream on the hot apple pie of art; both are good alone, but together they are delicious in ways never imagined.

‘History is a large dollop of ice cream on the hot apple pie of art; both are good alone, but together they are delicious in ways never imagined’

How did Medicine Man Gallery come about?

While I was practicing as a naval physician with the Marines, I purchased my first business license to sell art, in 1988, and by 1992 I realized I wanted to be an art dealer. This epiphany came after I was offered a prestigious job with a sports medicine group in Phoenix and realized I was at a crossroads in the river. I banked hard left—avoiding the easy, safe way down—and never looked back. You have few opportunities in life that require you to forget what’s smart and take a leap of faith; that was one of those moments.

How do you find time to do all of this?

I’m a man of routines, which would make me an easy mark in one of my murder mysteries. People say, “You must never sleep!” I make sure I always get eight hours, but the key is I never waste any of the time in between. While sleeping, I’m working out plotlines and problems while reinvigorating my body for the next day. I exercise daily, write daily, read daily and set goals short- and long-term, which help me manage my time. I’m curious, which leads me in new directions, like a podcast. The key I think to success is embracing the creativity that we all inherently have but so few use.

What is the art scene like in Tucson?

The art scene is robust in Tucson, with active groups in Western, Latin, native American and contemporary art. While we don’t have the number of galleries as Santa Fe or Scottsdale, the galleries we do have are long-term and committed to the arts.

And the Western history scene?

The Tucson Museum of Art is quite active in curating exhibitions showcasing the art of the American West, with their support groups offering trips throughout Arizona and lectures on relevant topics. We also support both the Arizona History Museum and the Arizona State Museum, which are equally essential to preserve the history of our state.

One concern many gallery owners, Western historians, publishers, etc., have expressed is that the clientele/readership is getting older and older. So how do we attract younger collectors/readers? The world changes but two things don’t: there will always be an American West, and the West will remain etched as a permanent part of the history of our nation. It is a problem that our collector and readership base are aging; however, often overlooked are the writers, publishers, historians and art dealers who are aging just as quickly. These are the drivers of the business. One reason I created the Art Dealer Diaries podcast, which focuses on Western and native art, artists, collectors and writers, is that I wanted to not only preserve our legacy but also reach an audience of young people who might find our profession just the lane they are searching for careerwise. I believe we must, as custodians of the history and material we hold dear and preserve, assure our profession continues to have relevance with the next generation by sharing our knowledge through technology, education and social media.

Is the future bright for Western history enthusiasts?

It’s more hazy. Video games like Red Dead Redemption keep the fires stoked for a younger audience that might find Western history through alternative methods. One of the reasons I do my Art Dealer Diaries podcast is to keep an active dialog in Western art and history in a format consumed by a younger audience. It’s up to those of us who love our field to share our passion with the next generation.

Who are your favorite contemporary Western artists?

I collect all the artists I represent in my gallery, which makes it hard to pick a favorite, as all these individuals have an original vision and voice in Western art. That resonates with me as a collector. I will say I have acquired a large number of Ed Mell, Howard Post, Josh Elliott and Stephen Datz paintings, along with many others, most of whom I represent.

What’s the hardest part of your job?

I have never thought of my job as being hard. Working in an emergency room near the I-5 and 405 interchanges in L.A.—now, that was a hard job! I think the most challenging aspect is making sure all our artists are represented equally regardless of sales.

What’s your favorite space in Medicine Man Gallery?

The Maynard Dixon Museum. It’s a quiet, contemplative space, and I can surround myself with the lifework of a master artist. I can feel history pulsating through the paintings, and understand what it took for Dixon to create each piece and why it was a pivotal work for the artist at that time in history.

What’s next for you?

I want to continue to innovate with the changes required to be pertinent as a gallerist in the 21st century. Writing will continue to be a creative outlet for me, as is my Art Dealer Diaries podcast. I don’t see this changing anytime soon. As I said, I’m a man of routines. WW