While establishing fast and reliable airmail routes to and across South America, trailblazing aviator Jean Mermoz became a national hero.

On December 7, 1936, French adventurer and aviator Jean Mermoz took off from Dakar, Senegal, in his four-engine Latécoère 300 flying boat for a flight across the South Atlantic to Brazil. It was to be his 24th crossing, but after a brief radio message, Croix du Sud and its veteran five-man crew vanished, never to be seen again.

Born on December 9, 1901, in the rustic village of Aubenton in northern France, Mermoz was a quiet and reserved youth who thought he might become a poet or perhaps an artist. Instead, he became a national hero famed for his pioneering airmail flights linking France to South America.

Advised by a family friend to go into aviation, Mermoz qualified as a military pilot in 1921. Once posted overseas to Syria, he distinguished himself by surviving a grueling four-day desert trek after a forced landing. The fiercely independent Mermoz, although a decorated pilot, disliked military life and was demobilized in March 1924.

Adrift in Paris and looking for steady work, Mermoz found himself frequenting soup kitchens. Airlines were hiring, but many other pilots were also scratching for jobs. Finally, Mermoz received a letter from Didier Daurat, Latécoère Airline’s director of operations, offering employment.

As early as 1918, Toulouse industrialist and warplane manufacturer Pierre Latécoère had planned an airmail service linking France to Africa and South America. Latécoère proposed flying mail between France and South America in as little as 7½ days, at a time when post might take three weeks by ship. To many, his vision was a pipe dream: “Utterly utopian,” exclaimed a French bureaucrat. Latécoère relished proving naysayers wrong.

Lignes Aériennes Latécoère (or simply the “Line” to its loyal employees) began its march into history in 1919 with 12 pilots and eight war surplus Breguet 14 biplanes linking France to North Africa by hopping down Spain’s east coast across the Mediterranean Sea. It wasn’t a job for the timid. In the first 15 months of service, six pilots died in crashes.

Mermoz’s many contributions to the Line’s colorful saga began in the fall of 1924. He initially flew mail from the company’s base at Toulouse over the Pyrenees to Spain, then later to French North Africa and finally on to Dakar in West Africa.

In an age when engine failures were frequent, flying the old Breguets over mountains and trackless deserts was truly an adventure. Latécoère’s pilots had to contend with extreme desert heat that caused engine radiators to boil over and violent sandstorms that suddenly blocked their paths, not to mention hostile Moorish tribesmen who roamed the deserts below.

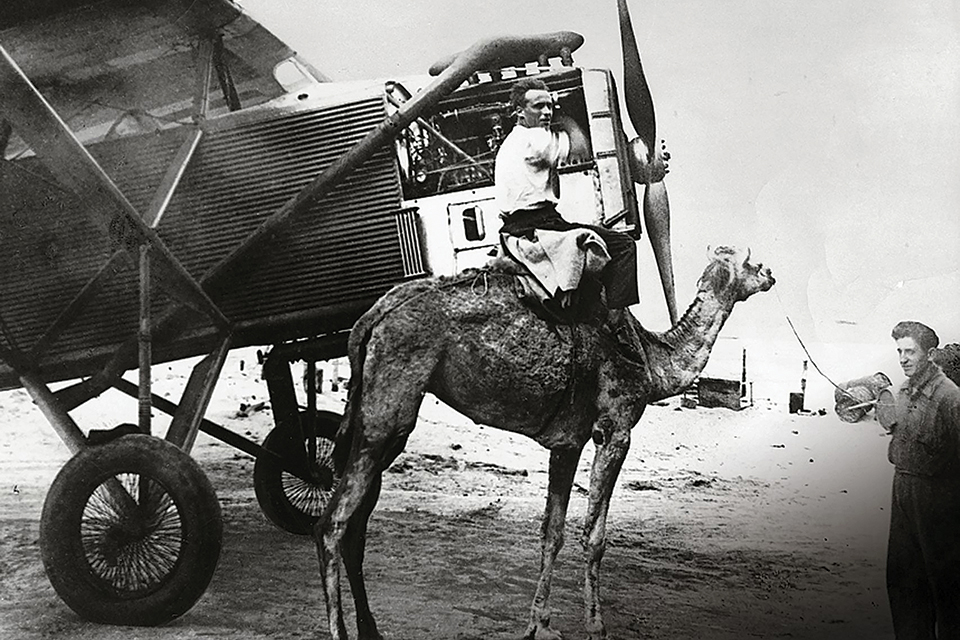

In May 1926, while flying the most remote and dangerous section of the Line, Casablanca to Dakar, Mermoz was forced down in the Sahara and captured by desert nomads. Ransomed by the carrier after days of captivity lashed to a camel’s back, he considered himself lucky. Tribesmen killed many who fell into their hands. A few months later, Mermoz would vainly search for other Latécoère airmen forced down by mechanical problems. Two were murdered outright, while a third man died of wounds soon after being ransomed.

To reduce losses, Latécoère Airlines began replacing the weary Breguets with more reliable Laté monoplanes of its own design. Facing financial hurdles, Latécoère changed hands in 1927 to become Compagnie Générale Aéropostale, or simply Aéropostale. What remained of Pierre Latécoère’s original company continued manufacturing planes.

That same year, Mermoz was appointed Aéropostale’s chief pilot in South America and immediately set to work expanding an airmail route system begun on that continent in 1924. Respected by fellow pilots for his courage, he led by example, taking great risks to shorten mail delivery times between distant cities. Quickly realizing that the best way to cut delivery times was flying at night, he decided to do just that with the primitive equipment then available. “It’s a terrible risk,” his boss had sensibly pointed out. “All right, I’ll take it,” countered Mermoz. “And if I can pull it off, others will do it after me.”

Mermoz made the first postal night flight between Natal, Brazil, and Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1928. Guided by bonfires along the route, he mastered the night. Aéropostale was no longer just a daytime operation.

Mermoz continuously sought new ways to improve mail service, which included scouting for a shorter route to Santiago, Chile, on the Pacific coast. In March 1929, Mermoz and mechanic Alexandre Collenot tried flying directly from Argentina to Chile by overflying the Andes—eliminating a lengthy 1,000-mile end run around the formidable mountain range. Because their Laté 25 monoplane was unable to climb above the towering mountains, Mermoz attempted to fly through a mountain pass, only to be slammed down onto a 12,000-foot high plateau by turbulence when nearly across. Stranded in subzero weather atop the plateau for three days without food or shelter, the two men realized there was no hope of rescue and set about repairing their damaged plane.

The resourceful Collenot repaired ruptured engine cooling lines and the plane’s empennage with scraps of clothing and leather strips cut from their flight jackets. After clearing a crude path down a rocky incline and muscling their plane into position for a short run along the pathway, they strapped themselves in and motored off the edge of the precipice. Pointing the nose straight down, Mermoz gained flying speed, and again, luck was with him. The engine worked long enough to reach the safety of the Chilean plain below.

The Chileans, incredulous that anyone could survive three days trapped high in the freezing cordillera without proper equipment, at first refused to believe it. With this escape, Mermoz’s myth of indestructability was born.

After acquiring higher flying Potez 25 biplanes able to surmount the Andes, Aéropostale initiated scheduled airmail service between Buenos Aires and Santiago over routes scouted by Mermoz. Now the challenge was connecting Aéropostale’s two “halves” by air. And for that Daurat again called upon Mermoz.

In bridging the Atlantic, Mermoz was about to embark on the riskiest adventure of his flying career. Departing from Senegal on May 12, 1930, aboard a Laté 28 floatplane loaded with mail just arrived from France and enough fuel for 30 hours of flight, Mermoz and two crewmates sought to connect Aéropostale’s African and South American route systems in one mighty leap. Previously, all “airmail” had made the five- to six-day ocean crossing between Dakar and Natal aboard fast packet ships.

Flying into the night, Mermoz encountered a surreal seascape of towering waterspouts. Guided only by moonlight, he weaved around enormous pillars of water that rose up into the stormy night sky. Fellow Aéropostale pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry would later chronicle this dreamlike experience in his classic Wind, Sand and Stars: “Through these uninhabited ruins Mermoz made his way, gliding slantwise from one channel of light to the next, flying for four hours through these corridors of moonlight.”

The big floatplane, named Comte-de-La Vaulx and powered by a single Hispano-Suiza water-cooled engine, performed flawlessly. Mermoz and his stalwart companions covered the 1,890 miles to Natal in 21 hours, 24 minutes. His was the first nonstop mail flight connecting the two continents. Celebrating his friend’s many adventures, Saint-Ex concluded, “Pioneering thus, Mermoz had cleared the desert, the mountains, the night, and the sea.”

Mermoz and his crewmates became national heroes, not only in their homeland, but in Argentina as well. In Buenos Aires they were wined and dined like movie stars, and the dashing Mermoz in particular was the toast of the town. With operations now spanning three continents and an ocean, these were indeed the best of times for Aéropostale’s pilots.

With the epoch-making transatlantic flight, Pierre Latécoère’s vision was at last fulfilled. Mail service between France and South America in only 4½ days! But the price was high: In the 12 years from Toulouse to Santiago, 121 airmen had lost their lives. Reflecting on the risks, Mermoz once confided to a friend, “For us…an accident would be to die in bed.”

Although bigger multiengine flying boats able to fly transoceanic mail were ordered in 1930, economic and political woes had caught up with Aéropostale. The continuing worldwide depression had sapped it financially, and with promised government aid withdrawn, the Line was essentially bankrupt. Despite its proud legacy, Aéropostale was nationalized along with four other airlines to form Air France in 1933.

During the commotion associated with the formation of Air France, Mermoz embarked on a series of long-distance flights popularly called “raids” by the French. In January 1933 he flew a Couzinet 70 trimotor landplane from Senegal to South America and back, setting new world records for aircraft performance in the process. The sleek-looking monoplane was ahead of its time, giving France a technical edge over rivals. The Couzinet 70’s reliability demonstrated that regular transatlantic airmail service was possible, with Mermoz later making additional crossings aboard the elegantly named Arc-en-Ciel (Rainbow), his preferred mount for long overwater flights.

Nearly a year after Mermoz’s triumphal return to South America in Couzinet’s powerful trimotor, the graceful Latécoère 300 seaplane made its first ocean crossing to Natal on January 3, 1934. Developed to meet requirements for a flying boat able to carry a 1,000-kilogram (2,200-pound) payload across the South Atlantic, it was powered by four Hispano-Suiza engines arranged atop the wing in a back-to-back pusher-puller configuration. About the size of a Martin M-130, the French courier plane—remarkable then for its ability to carry nearly its own weight in fuel and mail—was conceived to carry mail only, not passengers. Christened Croix du Sud (Southern Cross), the swanlike flying boat was a plodder, cruising the skies at a leisurely 99 mph.

In Arc-en-Ciel, Air France had a faster aircraft for its Atlantic mail runs. And by the mid-1930s, France was competing with a resurgent Germany, which had developed its own mail service across the South Atlantic using Zeppelins and airplanes. To meet the challenge, Mermoz had championed Couzinet’s efficient landplane. However, the French Air Ministry, favoring seaplanes for overwater flying, opted for three more Laté 300 series flying boats, while refusing to authorize additional Couzinet planes.

Prior to 1936, most French mail still continued crossing the Atlantic by ship. But in January of that year, with great fanfare, Air France had inaugurated weekly transatlantic mail flights. The service had barely gotten underway however, when a Laté flying boat was lost.

Although the Laté 300 easily flew the South Atlantic nonstop, the flying boat had issues, especially with its complicated 740-hp V-12 engines. Mermoz had expressed doubts about the type’s reliability, particularly after his favorite mechanic Alexandre Collenot was aboard a Laté that disappeared off Brazil’s coast in February 1936. Despite persistent mechanical problems, the Latés continued plying the Atlantic on mail runs.

On December 7, two days before his 35th birthday, Mermoz launched from Senegal aboard Croix du Sud for a scheduled run to Natal, only to quickly return with a propeller problem on the right rear engine. With no replacement aircraft available, and focused on keeping his schedule, Mermoz ordered a speedy repair and departure, urging, “Quick, let’s not waste time anymore.” Four hours after departing again for Natal, Dakar’s radio station received a terse message from Croix du Sud: “Cutting right rear motor.” Then nothing.

“We must still look for Mermoz,” pleaded Saint-Exupéry in a French newspaper column a week after his close friend went missing. After all, the great Mermoz had disappeared before, only to reappear after yet another miraculous escape. But not this time—nary a trace of the plane or crew was ever found.

Hailed as the “French Lindbergh” by the American press, Mermoz was a French cultural hero whose flights across the Andes and South Atlantic were the first of their kind. And knowing full well the dangers involved living his life of adventure, he wrote his own epitaph when he remarked to Saint-Ex: “It’s worth it…it’s worth the final smash-up.”

For his extraordinary achievements, Jean Mermoz was made a commander of the Légion d’Honneur by a grateful French nation in 1934.

Robert Bernier is an aircraft restoration volunteer at the San Diego Air & Space Museum. For further reading, he recommends Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: His Life and Times, by Curtis Cate, and Saint-Ex’s Wind, Sand and Stars.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!