A look at Louisiana’s World War II training grounds

IN SEPTEMBER 1941, as German troops raced toward Moscow and Japan extended its reach across the East, the United States was still playing war games. Throughout that month, the U.S. Army staged the Louisiana Maneuvers, the most extensive field exercises in its history. Thousands of nascent GIs in World War I–style helmets fought sham battles across central Louisiana’s prairies, cotton fields, and pine-covered hills. Today travelers come to the region to see antebellum plantations and Civil War sites, but for me it was the Second World War that beckoned. Seventy-six Septembers after the 1941 maneuvers, I rented a car and explored the “battlefields” of Louisiana.

The outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 forced preparedness on America, and in 1940 the army selected central Louisiana as a training ground. The warm climate allowed year-round operations, and the remote woodlands of Kisatchie National Forest offered plenty of space. Camp Beauregard, a mothballed World War I camp just north of Alexandria, sprang back to life. In 1940–41 the army carved three more facilities out of national forest lands: Camp Livingston, 10 miles north of Alexandria; Camp Claiborne, 18 miles south of Alexandria; and Camp Polk, eight miles southeast of Leesville.

The maneuver area was vast, ranging from East Texas to Louisiana’s eastern border, with the Red River bisecting it. The action occurred in two phases, pitting Lieutenant General Benjamin Lear’s Second Army against Lieutenant General Walter Krueger’s Third Army. Participants included a veritable who’s who of future World War II commanders. Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower was Krueger’s chief of staff. Major General George S. Patton led the 2nd Armored Division. General Headquarters Chief of Staff Lesley McNair, known as the “brains of the army,” supervised the exercises. All were under the watchful eye of U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall.

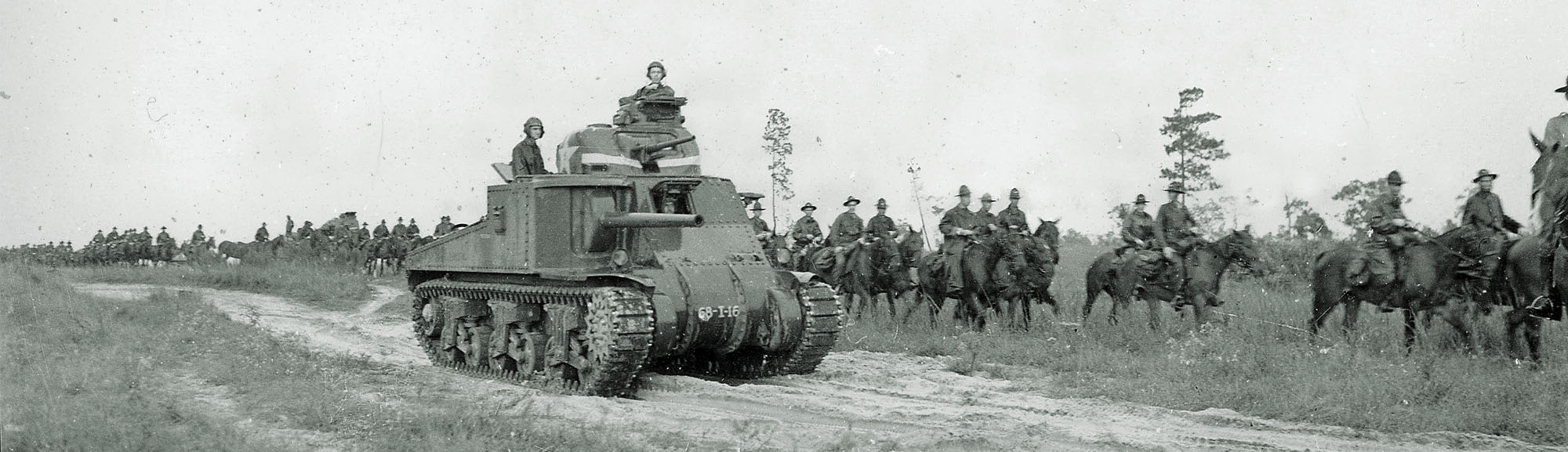

Nearly half a million troops participated. In light of Hitler’s blitzkrieg across Europe, McNair was especially keen to test America’s armored forces, with the army’s M2 and M3 tanks playing the lead roles. Infantry, artillery, air forces, paratroopers, and even cavalry troopers on horseback took part as well—not to mention critical support troops. McNair trucked in mountains of blank rounds and even played recorded battle noises to add authenticity. Obviously, some actions had to be simulated, such as airstrikes and the destruction of bridges. Equipment shortages also hindered realism. Antitank guns, to give just one example, were often made of logs.

Just as the first exercise was about to begin, on September 15, a tropical storm soaked the troops in the field. But the training went on: General Lear, based north of the Red River, attacked Krueger’s forces to the south, camped on the flat prairies between Lake Charles and Lafayette. Lear planned an armored sweep around Krueger’s left flank, but his slow advance allowed Krueger to blunt the attack, reposition his forces, and grab the initiative.

The second exercise, nicknamed the “Battle of the Bridges,” commenced on September 24 with another drenching storm. In this scenario, Lear defended Shreveport from Krueger’s forces attacking from the south. Lear traded space for time, destroying bridges (in simulated fashion, of course) as he retreated northwesterly up Red River Valley, forcing Krueger’s engineers to construct hundreds of pontoon bridges—right alongside those already declared destroyed. The most dramatic event was Patton’s armored sweep through East Texas, getting behind Lear and approaching Shreveport from the north.

Though the fighting may have been simulated, the casualties sometimes were real. A pilot died in a midair collision on the first day. In another incident, two soldiers drowned trying to cross the rain-swollen Cane River near Natchitoches. But there were moments of levity, too. According to one oft-told story, maneuver umpires declared a bridge wrecked, only to see soldiers walking across it. “Can’t you see that bridge is destroyed?,” yelled the umpire. “Of course,” one soldier responded. “Can’t you see we’re swimming?”

By the time the maneuvers ended on September 28, the soldiers had gained some insight into the rigors of a war campaign. Commanders got experience, too—and many who were found lacking the necessary skills lost their jobs.

Louisiana remained an important training ground once the U.S. entered the war. The famed 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, for example, were reactivated at Camp Claiborne in 1942. After the war, Polk and Beauregard remained in army hands. Claiborne and Livingston were abandoned, and the Kisatchie National Forest swallowed them up.

Tourists today will find most maneuver-related sites within an hour’s drive of Alexandria. Perhaps the best place to begin your explorations is the Louisiana Maneuvers and Military Museum at Camp Beauregard, which houses artifacts from the war years, including uniforms, equipment, weapons, and maps.

But for me, the ruins of the abandoned camps held greater allure. My first stop is Camp Livingston. There is no interpretive signage at the site, but fortunately the director of the Louisiana Maneuvers museum, Richard Moran, offers to show me around. He takes me down a nondescript rural road and, before long, broken concrete slabs and crumbling vestiges of warehouses and loading docks begin to appear among the tall, fragrant pines and tangled underbrush. The shady streets have not been maintained since Roosevelt was in office and are riddled with heaves and potholes. Everything is covered with pine needles, except for a narrow path down the main road where a few vehicles occasionally pass. The war feels distant; it is hard to imagine these streets crammed with soldiers and trucks or the sound of “Reveille” in the morning.

Among the spots Richard shows me is the old camp recreation area. The swimming pool is overgrown with brush, the deep end filled with stagnant green water. Nearby stand pillars that once supported the gymnasium walls, rising ghost-like from the forest floor. Graffiti artists have tagged the ruins, while discarded clothing, beer cans, and multicolored shotgun shells lay on the ground among the pinecones.

Next I visit Camp Claiborne, the ruins of which stretch a couple of miles along State Highway 112. A few information panels mark the site of the old camp headquarters, where the 82nd and 101st Divisions were rebranded as airborne units. As at Camp Livingston, enigmatic concrete ruins dot the forest. Weathered sidewalks lead to nowhere. The woods are eerily quiet, sounds muffled by 70 years of accumulated pine needles.

One sunny morning, I drive along the south bank of the Red River from Alexandria toward Natchitoches, about 50 miles northwest. Several tributary rivers and streams cross my path, most notably the Cane River, which meanders through snow-white cotton fields that seem ready to burst. The river runs slow and lazy—not like the storm-swollen torrent of 1941—but I nonetheless think about the two soldiers who died trying to cross it, and the hard work of the engineers during the “Battle of the Bridges.”

I then turn westward and drive through the wooded uplands, sharing the road with rumbling trucks hauling timber stacked like giant matchsticks. A portion of State Highway 118 between Florien and Kisatchie, an area that saw considerable action in the first maneuver, is now designated the Louisiana Maneuvers Highway. A historical marker along the road at Peason Ridge highlights the impact of the war on that rural community. In 1941 the army forced its 25 resident families off their lands to create a permanent training ground. Small weather-beaten display cases poignantly exhibit memorabilia about life there before the war. There are numerous photographs—smiling families, proud couples, a bearded Confederate veteran, and a local boxer, fists up, ready to fight. Soldiers still train at Peason Ridge today.

As the hazy orange sun sinks into the west, I head toward New Orleans, where the next day I pay a visit to the impressive National World War II Museum. I walk through its exhibits—numerous and marvelous—but my mind drifts back to the countryside, just a few hours to the north, where the woods and fields have their own stories to tell.

Alexandria is the best base for exploring the maneuvers area. Alexandria International Airport is served by American, Delta, and United airlines. In addition to Camp Beauregard’s Louisiana Maneuvers and Military Museum (geauxguardmuseums.com), the Fort Polk Museum (jrtc-polk.army.mil/museum.html) and Long Leaf’s Southern Forest Heritage Museum (longleaf.la) also have exhibits about the maneuvers.

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

Alexandria’s Hotel Bentley (hotelbentleyandcondos.com) offers the area’s most elegant lodging option. The likes of Eisenhower and Patton once walked its fine mosaic floors and marbled hallways. Inside is a small exhibit of the war years. Louisiana is noted for its unique Cajun cuisine. The southern edge of the maneuvers area between Lake Charles and Lafayette offers the best options for tasty boudin, crawfish, and gumbo.

WHAT ELSE TO SEE AND DO

Camp or hike Kisatchie National Forest (fs.usda.gov/kisatchie), but bring your bug spray. The maneuvers passed through what is today the Cane River Creole National Heritage Area (nps.gov/crha), south of Natchitoches, which preserves the area’s multicultural history. During the Civil War, real battles raged in Red River Valley: Mansfield battlefield and Forts Randolph and Buhlow are both maintained by Louisiana State Parks (crt.state.la.us/Louisiana-state-parks).