I had dreamt for over 40 years of walking the battlefield in Mongolia. I’d written my doctoral dissertation about the Soviet-Japanese conflict at Nomonhan from May to September 1939—an undeclared war, also known as the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, that shaped the course of World War II—and it became the centerpiece of my academic career. Years later, I was a keynote speaker at a conference commemorating the battle’s 70th anniversary in Ulaanbaatar, the Mongolian capital. I was disappointed when our hosts cancelled a tour of the battlefield, near the Chinese border, deeming it too arduous. So I made my own arrangements, hiring a car, driver, and interpreter. Extracts from my travel journal follow.

The first leg of Monday’s trip is a 410-mile flight from Ulaanbaatar to Choibalsan, capital of Dornod, Mongolia’s easternmost province. Dornod Province is home to 75,000 people, half of whom live in Choibalsan. My interpreter, Urgoo, teaches high school English and computers, and is very eager to please. He and my driver, Enkhbat (Mongolians typically go by just a first name), don’t let me carry anything from the airport. The hotel—the best in town, one star—lays out an enormous meal for me. Each course is enough for five people. I’m the only guest in the dining room. I ask if this is a normal meal. Urgoo says, “No, but we served this for you out of respect.” They had seen my interview on Mongolian national TV at the conference. I’m a celebrity!

Tuesday morning dawns bright and sunny. Our vehicle is a large diesel-powered, air-conditioned Toyota Land Cruiser. By the time we reach the eastern outskirts of Choibalsan, the road—the major east-west artery between Choibalsan and the Chinese border—has become an “improved” dirt road. Soon it’s no longer improved. We cross 175 miles of dirt road, traversing the Mongolian steppe, a seemingly endless flat grassland with occasional slight undulations. Rains have left standing water and mud, but Enkhbat, an expert driver, avoids these by simply driving onto the grass. We average around 30 miles an hour, at times crawling over obstacles in low gear and at other times hitting 60 miles an hour. It is not a smooth ride. On the seven-hour trip, only four vehicles pass us going west, and we overtake about eight eastbound. Mongolia is Big and Empty.

As we approach Khalkin Gol it turns cool with dark storm clouds, but we encounter only light rain. On arrival, Urgoo says, “We were lucky with the rain.” I agree, imagining a quagmire. He explains, to my surprise, that when travelers bring rain with them it’s considered good luck. Water is precious on the semiarid steppe.

In 1939, what is now the town of Khalkhin Gol was nothing but grassland. It is a sad, impoverished-looking place, home to about 3,000. No industry. A few shops serve a small tourist season that lasts about three months a year. The main economic activity is agriculture, and people appear to be just scraping by. Many of the concrete buildings are abandoned and decrepit. No municipal water or sewage. Residents draw water from a central well. I meet the chief administrative assistant to the governor of the district; a few minutes later he’s using a public outhouse.

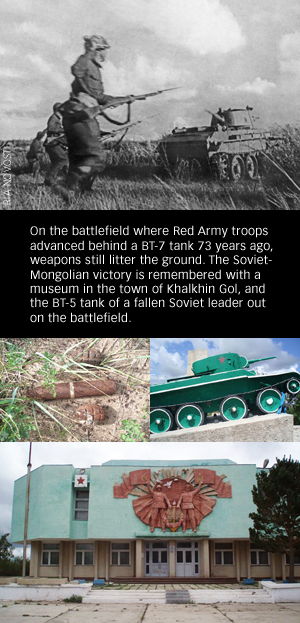

We stay at a “hotel” (five or six rooms for rent) in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol Victory Museum. The two-story communist-era concrete structure celebrates the Soviet/ Mongolian victory in this little-known conflict, which helped trigger the outbreak of World War II and influenced decisions in Tokyo and Moscow that shaped the conduct and outcome of the war. (See “A Long Shadow,” May 2009, available online.) The museum is the town’s most impressive structure—but poorly lit and shabby.

If the hotel in Choibalsan was one star, this place is a negative number. I have the best room: two small twin beds, a tiny wooden desk and stool, an overhead fluorescent light, and a single wall outlet. A filthy toilet (BYO toilet paper) down the hall has a matching sink (BYO soap and towel) that emits a dribble of cold water. No shower or tub. Yet these amenities make the museum the finest lodging in town, as it has running water and one does not have to use a public outhouse. The next time I bathe will be in four days.

On Wednesday we finally enter the battlefield a few miles outside town. We start at the victory monument the Soviets erected atop a hill on the west bank of the Khalkha River: a modernistic tapered steel spire pointing skyward some 200 feet, overlooking the site where General Georgi Zhukov, who would lead the Red Army to victory over Germany, defeated the Japanese in his first major combat command.

On Wednesday we finally enter the battlefield a few miles outside town. We start at the victory monument the Soviets erected atop a hill on the west bank of the Khalkha River: a modernistic tapered steel spire pointing skyward some 200 feet, overlooking the site where General Georgi Zhukov, who would lead the Red Army to victory over Germany, defeated the Japanese in his first major combat command.

At a border garrison post, we confirm our plan to visit battle sites near the Mongolia-China border. The post commander, a young Mongolian lieutenant, heard from his superiors that an “important American scholar” was coming. He gives us a personal tour of his section of the battlefield, riding with us for three hours, giving directions to Enkhbat and explanations to me. He takes us everywhere I want to go and then some, including battle sites that foreign visitors rarely see.

He points out faintly visible depressions in a hillside—Japanese antitank traps, softened by 70 years of erosion. We come upon a small monument that I did not know existed: a stark gray slab on Remizov Heights marking the spot where Major I. M. Remizov, a regimental commander later named a Hero of the Soviet Union, fell in July 1939 while repelling a Japanese assault. I stand with awe on Fui Heights, the northern anchor of the Japanese line in the late-August climax of the battle, where a mixed battalion of 800 Japanese infantry held off a Soviet force of over 10,000 mechanized infantry and armor for three days before being driven from the heights, enabling Zhukov to encircle and annihilate the Japanese Sixth Army.

The lieutenant leads us to an unmarked site and starts poking around in the loose sandy soil with the toe of his boot, digging up artifacts he presents to me as gifts: a Japa-nese rifle cartridge case, half a dozen slugs, a rusted bayonet blade and scabbard, a few 37mm antitank rounds, and three hand grenades. I attri-bute this seemingly casual largess to my status as the “important American scholar.” Most of these treasures will not make it past the three airport security screenings I undergo between Khalkhin Gol and my Maryland home, but as I write this, the spent bullets are on my desk, reminders of the brave men who fought and died on that remote battlefield.

The last stop is a tour of the Victory Museum conducted by its director. Though small, the facility has interesting displays of weapons, equipment, uniforms, maps, and battlefield photos, as well as a heroic wall mural of the Battle of Bain Tsagan, whose location we’ll visit tomorrow. After supper there’s absolutely nothing to do: no movies, no TV, no bar, nothing. After updating the day’s events on my laptop, I read in bed and go to sleep early.

Thursday is another day of battlefield touring, this time on the west bank of the Khalkha. The main attraction is the high ground of Bain Tsagan, from which Zhukov hurled several hundred tanks and armored cars, unsupported by infantry, against 8,000 Japanese troops that had crossed the river in a surprise attack on July 2, 1939. That morning, the Soviets lost 180 armored vehicles, but halted the Japanese advance. We continue north along the river’s west bank, viewing more sites and monuments: the tank in which Colonel M. P. Yakovlev, another Hero of the Soviet Union, died in July defending the Soviet bridgehead, and an iron tank barricade symbolically marking the farthest point of Japanese advance west of the river.

Near the end of our excursion we stop at another border post. A lieutenant is waiting outside as our car approaches. Would we please do him a favor, he asks, and drive his wife, daughter, and mother-in-law to her home, about 25 miles north? Sure, it’s right on our way.

Stuart D. Goldman has been the Scholar in Residence of the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research since 2009. From 1979 to 2009, Goldman was the senior specialist in Russian and Eurasian political and military affairs at the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress. His latest book Nomonhan, 1939: The Red Army’s Victory That Shaped World War II is on the little-known Battle of Khalkhin Gol (also known as Nomonhan), and its profound consequences.

Stuart D. Goldman has been the Scholar in Residence of the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research since 2009. From 1979 to 2009, Goldman was the senior specialist in Russian and Eurasian political and military affairs at the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress. His latest book Nomonhan, 1939: The Red Army’s Victory That Shaped World War II is on the little-known Battle of Khalkhin Gol (also known as Nomonhan), and its profound consequences.

When You Go

Khalkhin Gol is in eastern Mongolia near the Chinese border. The best time to visit is June through August. Winters are brutally cold; heavy snows begin in late September. There are no direct flights from the United States, but Ulaanbaatar is a destination from Seoul on Korean Air, Tokyo on ANA, and Beijing on Air China. Once there, Eznis Airways flies daily to Choibalsan. There is no public transportation to or in Khalkhin Gol. A four-wheel-drive vehicle and local guide are indispensable. I booked my tour through ETI Group (info@eti.mn; 976-99118959).

Where to Stay and Eat

In Choibalsan I stayed and ate at the Ikh Ursgal Hotel. There are four other hotels, none up to international standards. In Khalkhin Gol lodging at the Khalkhin Gol Victory Museum is grim but it’s the only choice. That said, you’re going for a unique experience, not a posh vacation.

What Else to See

In Choibalsan, the G. K. Zhukov Museum highlights Marshal Zhukov’s role in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, but also includes other facets of his remarkable career. The Danrig Danjaalin Khiid Buddhist Monastery once housed 400 monks; today it has 15, who welcome visitors.