The ‘Gray Ghost’ and his men hampered Union efforts in Virginia with midnight raids and strategic scheming

Civil War Trails’ walking and driving tours offer the perfect opportunity to safely stretch your legs and escape into history. America’s Civil War will highlight places to visit accessible under social distancing regulations while they remain in place.

Although Northern Virginia’s reputation is often married to the hustle and bustle of the surrounding Washington, D.C.–metropolitan area, the region is also peppered with some of the country’s oldest, most charming, and sedate historic towns, including bucolic hamlets nestled in the Bull Run and Blue Ridge mountains. It’s almost impossible to travel through any of them without stumbling across a story about Colonel John Singleton Mosby and his Partisan Rangers. Between his audacious nighttime raids, his stealth movement between hideouts, and his cavalry’s consistent clamor, Mosby dominated the area in the war’s latter years. His haunting threat loomed over the Union efforts here, and many dubbed it “Mosby’s Confederacy.” “My purpose,” he declared, “was to weaken the armies invading Virginia, by harassing their rear….To destroy supply trains, to break up the means of conveying intelligence, and thus isolating an army from its base, as well as its different corps from each other, to confuse their plans by capturing their dispatches, are the objects of partisan war. It is just as legitimate to fight an enemy in the rear as in the front. The only difference is in the danger.” Known today as the Mosby Heritage Area and maintained by the association that shares its name, it’s bounded by the Bull Run Mountains to the east, the Blue Ridge to the west, the Potomac River to the north, and the Rappahannock River to the south. The 1,800-square-mile tract hosts a bevy of Mosby-related locations to visit. Mosby’s spirited personality enlivened nearly every encounter or engagement he partook in, and Civil War Trails signs throughout Northern Virginia share the colorful stories of his reign over the region. Whether you visit one or all, you can be sure, with Mosby, it won’t be a dull ride. —Melissa A. Winn

[hr]

Chapman’s Mill

17504 Beverly Mill Dr., Broad Run

In 1861, Confederates used this mill as a meat-curing center and distribution warehouse. Mosby and his men used the road and gap here throughout the war. When Confederates withdrew from the area in March 1862, they burned the mill and its contents, including 2 million pounds of meat, to prevent it from falling into the hands of Northern forces. On August 28, 1862, the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap erupted in and around the mill. Owner John Chapman sued the government for damages but lost. Ruined economically, physically, and emotionally by the mill’s destruction, his family committed him to an asylum in 1864. The mill was restored in 1878 and remained operational until a fire in 1998 reduced it to ruins. Efforts are under way to restore it again.

[hr]

Mosby’s Men Disband

Frost Street and Main Street, Marshall

About a block away from the current site of the Fauquier Heritage and Preservation Foundation, Mosby called his men together on April 21, 1865, to notify them: “I have summoned you together for the last time….I am no longer your commander. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering to our enemies.”

About a block away from the current site of the Fauquier Heritage and Preservation Foundation, Mosby called his men together on April 21, 1865, to notify them: “I have summoned you together for the last time….I am no longer your commander. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering to our enemies.”

[hr]

Measure for Measure

Maidstone Road, Rectortown

Mosby used this warehouse, still standing, to hold 27 Union prisoners ahead of the retaliation “lottery” he conducted after seven of his men were executed. Mosby’s prisoners were made to draw slips of paper from a hat: 20 left blank, seven marked for death. Early the next morning, the unlucky septet were marched to their execution site. In the darkness and confusion, two prisoners escaped. Two others were shot in the head and left for dead. Only grazed, however, they later managed to escape, but the remaining three were hanged. A placard placed on one of the executed Federals read: “These men have been hung in retaliation for an equal number of Colonel Mosby’s men hung by order of General [George] Custer at Front Royal. Measure for Measure.”

Mosby used this warehouse, still standing, to hold 27 Union prisoners ahead of the retaliation “lottery” he conducted after seven of his men were executed. Mosby’s prisoners were made to draw slips of paper from a hat: 20 left blank, seven marked for death. Early the next morning, the unlucky septet were marched to their execution site. In the darkness and confusion, two prisoners escaped. Two others were shot in the head and left for dead. Only grazed, however, they later managed to escape, but the remaining three were hanged. A placard placed on one of the executed Federals read: “These men have been hung in retaliation for an equal number of Colonel Mosby’s men hung by order of General [George] Custer at Front Royal. Measure for Measure.”

[hr]

Skirmish at St. Mary’s

11098 Fairfax Station Rd., Fairfax Station

With pistols blazing, Mosby and 39 of his men charged a line of Federal troopers here on August 8, 1864. Riding back and forth in front of his Rangers, Mosby shouted, “Come on men, victory or death!” The Union troopers broke and fled. Five were killed and 20 captured, along with 39 horses. During the war, Clara Barton used the church as a field hospital. It is located across the street from the Fairfax Station Railroad Museum, which highlights the station’s role from 1861 to 1865, including as a supply and medical evacuation site during the Second Battle of Bull Run.

With pistols blazing, Mosby and 39 of his men charged a line of Federal troopers here on August 8, 1864. Riding back and forth in front of his Rangers, Mosby shouted, “Come on men, victory or death!” The Union troopers broke and fled. Five were killed and 20 captured, along with 39 horses. During the war, Clara Barton used the church as a field hospital. It is located across the street from the Fairfax Station Railroad Museum, which highlights the station’s role from 1861 to 1865, including as a supply and medical evacuation site during the Second Battle of Bull Run.

[hr]

Caleb Rector House

14601 Atoka Rd., Marshall

John S. Mosby officially formed his first company of the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry in the parlor of this home on June 10, 1863. At the time of the Civil War, Caleb and Mary Ann Rector owned the home, located in Atoka, Va., formerly Rector’s Crossroads. The Mosby Heritage Area Association now calls the historic Caleb Rector House its headquarters.

[hr]

Mosby’s Wake-Up Call

10520 Main St., Fairfax

In March 1863, Mosby and his men knocked on the door of Dr. William Gunnell’s house in Fairfax, Va., where Union General Edwin Stoughton was staying. Stoughton’s 2nd Vermont had spent most of the war stationed in and around Fairfax. Rousing the general from his bed, Mosby asked, “Do you know Mosby, General?” The general replied, “Yes! Have you got the rascal?” “No,” said Mosby. “He’s got you!” Along with Stoughton, Mosby and his men rounded up more than 30 other prisoners and dozens of horses. When informed of the incident, President Lincoln allegedly said he regretted the loss of the horses more than Stoughton, claiming he could make another brigadier general in five minutes, “but I cannot make more horses.”

[hr]

Where It All Began

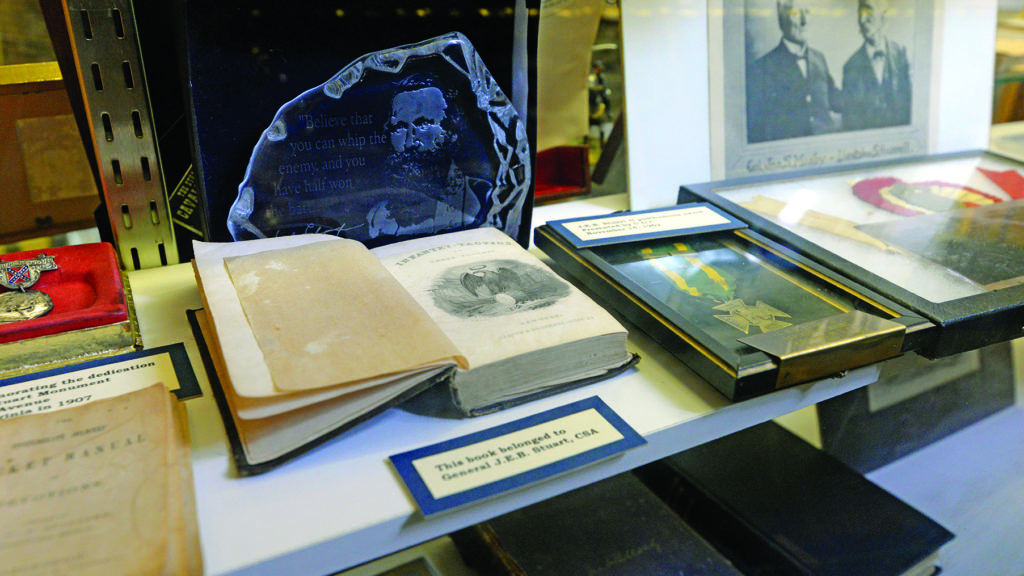

The Stuart-Mosby Civil War Cavalry Museum, tucked in the heart of Centreville’s historic district, displays artifacts related to Mosby and Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, Mosby’s commander and mentor before Mosby left to create what became the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry. The museum building was constructed with stones from Centreville’s historic Grigsby House, otherwise known as the “four-chimney-house,” which once served as Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s headquarters and where Mosby met Stuart for the first time. Contact the museum for hours of operation, which may be restricted for social distancing. 13938 Braddock Rd., Centreville

The Stuart-Mosby Civil War Cavalry Museum, tucked in the heart of Centreville’s historic district, displays artifacts related to Mosby and Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, Mosby’s commander and mentor before Mosby left to create what became the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry. The museum building was constructed with stones from Centreville’s historic Grigsby House, otherwise known as the “four-chimney-house,” which once served as Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s headquarters and where Mosby met Stuart for the first time. Contact the museum for hours of operation, which may be restricted for social distancing. 13938 Braddock Rd., Centreville

[hr]

[hr]

Ambush at Ewell’s Chapel

Loudoun Drive and Largo Vista Drive, Haymarket

On June 22, 1863, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade set a trap here for Mosby and his Rangers. A small detachment of the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry waited roadside as bait, while members of the 14th U.S. Infantry hid inside the chapel, which no longer stands. A misdirected volley, however, sent Mosby and his men, largely unhurt, galloping off to safety.

[hr]

Hopewell Gap

16513 Waterfall Rd., Haymarket

This narrow pass through the mountains was a strategic avenue for Union and Confederate forces. The rocky terrain enabled Mosby’s men to hold 153 prisoners and 200 horses at Camp Spindle near here during the summer of 1863. Mosby released two of the men, reporters for the New York Herald, who he hoped would report him as a “gentleman.”

This Trailside column appeared in the July issue of America’s Civil War.