The Macchi-Castoldi M.C.72 wrote a record-breaking epilogue to the Schneider Trophy races.

Jacques Schneider, the son of a French steel and arms manufacturer, was a great aviation enthusiast. He came to believe that floatplanes and flying boats were the most practical military and civilian design, since they could fly to any country with a coast, a river or a lake. On December 5, 1912, he announced a competition designed to encourage manufacturers of marine aircraft to develop the world’s fastest plane. The prize, which he called the Coupe d’Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, consisted of a silver sea wave 22.5 inches across with the figures of Neptune and his three sons, over which was poised the winged female personification of the Spirit of Flight, all set on a marble pedestal. In addition to the trophy, the winner received 1,000 pounds sterling.

The trophy was meant to be competed for annually, but any country that won three consecutive races could keep it permanently. It soon came to be known simply as the Schneider Trophy Race, and for almost 20 years it was the most prestigious competition in the aviation world.

By the mid-1920s, Schneider’s original purpose had been eclipsed by an international obsession with speed for speed’s own sake. National pride was on the line. By 1929, the race’s principal rivals had narrowed down to Britain and Italy. More specifically it pitted Supermarine’s chief engineer, Reginald J. Mitchell, against Aeronautica Macchi’s principal designer, Mario Castoldi.

Britain’s Supermarine S.6 won the 1929 race, its second win in a row—one more and Britannia would rule not only the waves but the air above them. But Italy and Macchi, which had last tasted victory in the 1926 race, were not about to concede without a fight. When the 1930 race was postponed, the Italians set out to win the next year’s competition in high style.

With the financial backing of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist government, Minister of Aviation Italo Balbo established a flying school, designated the Reparto Alta Velocita (high-speed section), on Lake Garda, with the sole purpose of putting seven specially selected pilots through 18 months of training for the 1931 race. Each man was trained in aircraft with five progressively higher speeds, from 300 kilometers per hour (more than 186 mph) to the hoped-for ultimate speed of 700 km per hour (435 mph). Pilots and mechanics alike had to familiarize themselves with hazards of racing aircraft, such as their dangerously high landing speeds of 125-155 mph.

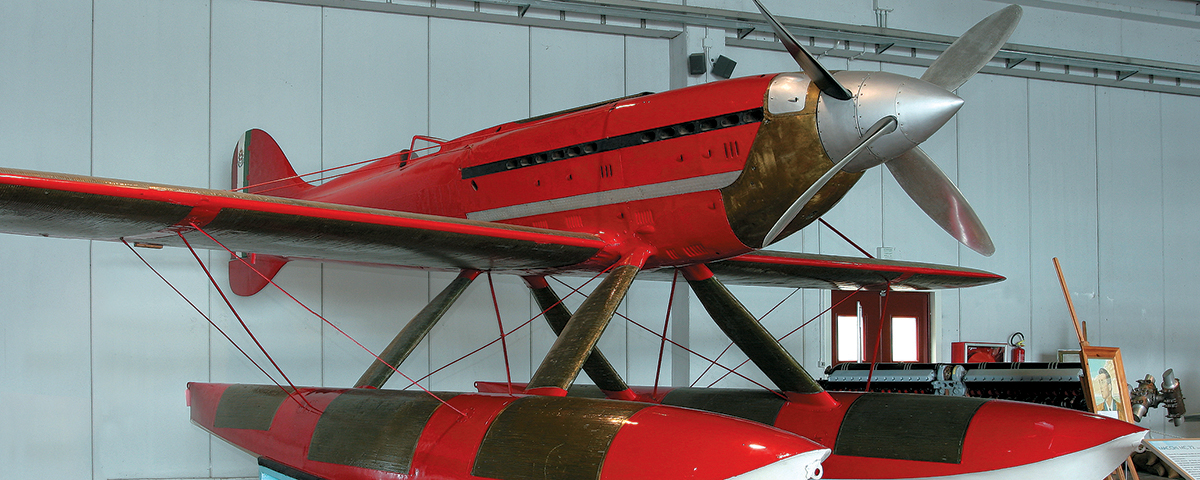

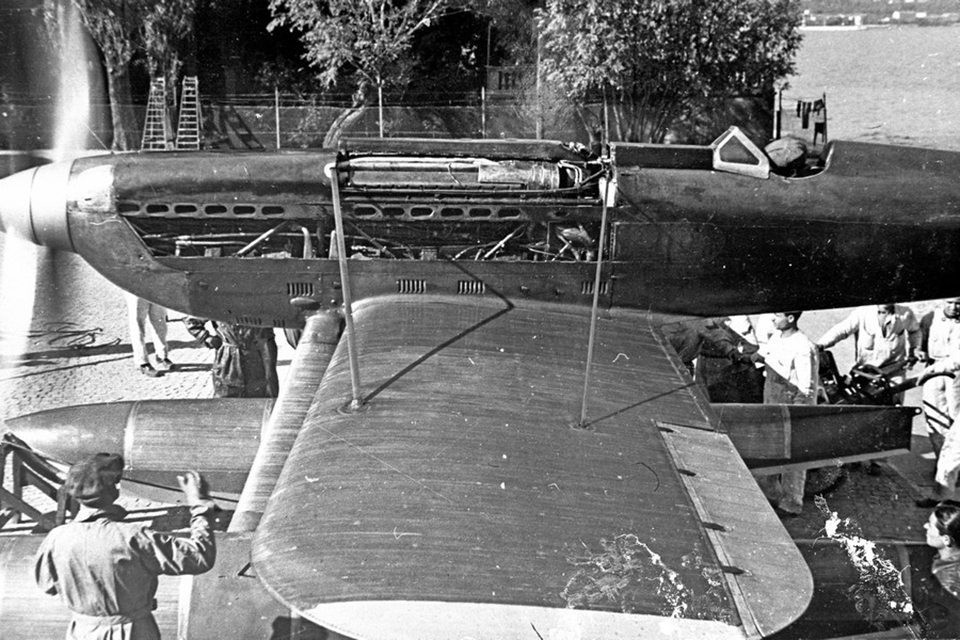

While the training went on, Castoldi designed his next Schneider Trophy entry around Tranquillo Zerbi’s new Fiat A.S.6 V-24 48-valve engine—or rather two 1,470-hp, 12-cylinder A.S.6s coupled in tandem, generating a total of 2,850 hp, which could be raised to 3,100 hp for short spurts. Each of the power plants was 11 feet long, weighed more than a ton and had two Marelli magnetos per valve. The two engines were connected by double reduction gears and concentric shafts to two contrarotating duralumin propellers, which eliminated the torque that had made takeoffs so hazardous for floatplanes in the past.

Just getting the double engine to work involved 18 months of testing and redesign. On April 20, 1931, it managed to run an hour before burning out two valves. Engineers went through about 1,000 valves, using 10 different types and grades of steel, before coming up with one that would stand up to the heat and stress.

Cooling the engines required radiators on every available surface, including the wings, fuselage, front of the floats and even the float support struts. The oil tank was in the lower front cowling, and two pumps circulated the oil in two stages. Four oil coolers with filters were installed in the rear of the floats. Fuel was housed within the floats and was independently drawn to each engine, which generated electric power for both fuel pumps.

The Macchi racer’s structure was of steel tubing covered with sheet duralumin forward of the wings, and wood with plywood covering aft, including the tail surfaces. The floats were all metal at first, but when they proved to be too heavy, new ones were built, using plywood for the lower part and duralumin for the upper part.

Castoldi’s new Schneider contender was designated the Macchi-Castoldi M.C.72 in his honor. Macchi originally planned to build five of the hot new floatplanes. Three were completed in 1931, but during an initial test in June 1931 the design team reported carburetion problems with the engine. That was only the beginning of the M.C.72’s troubles. On August 2, the first prototype, after reaching a speed of 375 mph, suddenly crashed, killing its pilot, Giovanni Monti.

On September 3, the Italians petitioned for the race to be postponed, but Britain refused, effectively eliminating Italy and France—whose entry was not ready, either—from participating in the 1931 race. Lieutenant Ariosto Neri and Stanislao Bellini kept test-flying in hopes of making the deadline, but during a September 10 flight Bellini was killed when his M.C.72 exploded in midair. At that point the question in Italy was no longer whether the M.C.72 could win the race but whether any of its pilots could fly it and live to tell the tale.

Meanwhile Reginald Mitchell had further refined his S.6 to use a new version of the Rolls-Royce R engine, which could generate 2,350 hp without a significant gain in weight over the 1929 model.

Originally scheduled for the second Saturday in September, the 1931 Schneider Trophy Race was held up for one day due to bad weather. September 13 was sunny and clear as the two contestants, both Supermarine S.6Bs, prepared to take off from Lee-on-Solent to begin the more than 217-mile course before an audience of almost a million, crowding the coast of Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight. As his blue and silver S.6B, S1595, was pushed off its barge near Calshot Castle, Flight Lt. John N. Boothman speculated on whether he could complete the triangular 33-mile laps seven times as planned—or if the cooling system would prove inadequate, causing the engine, which had hitherto never run longer than 27 minutes, to melt on its mountings.

Taking off at 1:02 p.m., Boothman ran the first lap in 5.5 minutes, averaging more than 343 mph and reaching almost 380 mph in the straightaways. From then on, his speed gradually deteriorated, until his seventh lap average was just under 338 mph. Nevertheless, Boothman had averaged 340.08 mph in a 47-minute flight, making the S.6B the fastest airplane in the world. Later that month, Henry Royce installed an engine capable of producing 2,600 hp for short sprints in S1595, and on September 29 Flight Lt. George H. Stainforth flew it on five straight 1.9-mile runs over Southampton Water, at one point hitting 415.2 mph and averaging 407.5 mph. The S.6B was the first plane to exceed 400 mph.

Although Italy’s ambitions had been dashed for the Schneider Trophy, Castoldi continued to work on his M.C.72. The Italians even enlisted the aid of British fuel expert Rod Banks, who eventually came up with a suitable mixture for the plane, comprising 54.5 percent gasoline, 22.5 percent alcohol, 21.5 percent benzol and 11⁄2 percent lead. But the M.C.72 remained a handful to fly, as Neri discovered on June 15, 1932, when he experienced dangerous flutter in the controls. He landed safely, but was killed three months later in a far-from-experimental Fiat C.R.20.

The hazardous task of flying the M.C.72 now went primarily to Warrant Officer Francesco Agello, who completed a successful test flight over Lake Garda on April 10, 1933. The press was told Agello would reach 700 kilometers per hour. After he landed, the average speed recorded was actually 681.97 km per hour (423.85 mph)—a little short of expectations, but a world speed record nevertheless.

Agello made more flights, but with frustrating results. The engine flamed out on May 13, he was forced to abort a June 4 flight after only eight minutes, and the engine suffered compressor failure on the 22nd. Serious vibrations forced him to abort on July 4, and another flight on October 1 was also unsuccessful. Finally, on October 8, Warrant Officer Guglielmo Cassinelli managed to fly 100 kilometers (62.1 miles) at an average of 629.37 kilometers per hour (391.071 mph). Another flight on October 13 resulted in more flameouts, and the M.C.72 went back to the shop for more work on the A.S.6 engine.

The M.C.72 did not make another record attempt until October 23, 1934, when Agello flew four laps over Lake Garda. This time he reached a maximum of 711.463 kilometers per hour (442.081 mph) and an average of 709.209 km per hour (434.7 mph), setting an absolute speed record that would not be broken until March 30, 1939, when Hans Dieterle reached 463.82 mph in a Heinkel He-100V-8, and April 29 of that same year, when Fritz Wendel edged it up to more than 469 mph in a Messerschmitt Bf-209V-1.

The M.C.72’s record speed for seaplanes would not be broken until August 19, 1961, when a Soviet Beriev Be-10 flying boat, powered by two Mikulin AM-3M turbojet engines and piloted by Nikolai Andrievsky, flew at 547 mph, but the M.C.72 still stands as the leader in the piston engine seaplane category. Trophy or no trophy, the Italians had the last word on the subject of speed.

In 1935 Italy hosted an airshow in Milan in which 17 Italian aviation firms, four French, four German, one Polish and one from the United States exhibited their latest products. Prominent among those displayed by Macchi was the record-breaking—and sole surviving—M.C.72.

The Schneider Trophy Race did much to boost speed in aviation. A.F. Sidgreaves, managing director of Rolls-Royce, claimed that the races had compressed 10 years of engine development into two years. But the competition did not really fulfill Jacques Schneider’s original vision of producing reliable flying boats. Instead the race ultimately led to the creation of more bellicose aircraft than its founder had had in mind, such as Mario Castoldi’s Macchi M.C.202 Folgore and M.C.205 Veltro fighters, or Reginald Mitchell’s famous Supermarine Spitfire.

As for the M.C.72, the sole remaining example has been preserved and can currently be seen at the Italian Air Force Museum at Vigna di Valle, near Rome.

Originally published in the January 2007 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.