In 1915 Gurkhas found themselves on the leading edge of the largest attack in the second year of World War I

On the morning of Sept. 25, 1915, just west of the village of Loos-en-Gohelle in far northern France, Captain Gerald C.B. Buckland of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Gurkha Rifles, realized something had gone decidedly wrong. After crossing no-man’s-land with the first wave of attackers, his company was supposed to tie in with another friendly unit to its right—but no one was there.

Exposed at the vanguard of the failed assault, Buckland’s men were running low on ammunition. It was only a matter of time before the Germans realized the Gurkhas’ right flank was wholly exposed.

“If a man says he is not afraid of dying, he is either lying or he is a Gurkha.” So said Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, a former Indian army chief of staff whose four decades of military service began in the British Indian army in 1934. Renowned for their courage and tenacity under fire, the Gurkhas traced their ethnic lineage to tribes from the mountainous areas of northern India and Nepal and had originally been united in their fight against the British during that country’s conquest of India. They later joined forces with the British in their colonial wars and saw service in Burma, Afghanistan, the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War and other conflicts across the British empire. That tradition of service continued through World War I, during which more than 200,000 Gurkhas served in homogeneous units led by British officers. Gurkhas saw action in the Middle East and Western Europe, playing a particularly important supporting role in the Sept. 25– Oct. 8, 1915, Battle of Loos, the largest British attack of the year.

By then the war had bogged down into a stalemate, leaving the opposing armies entrenched along a front stretching more than 400 miles from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Allied commanders hoped to break the impasse with two big pushes—the French concentrating on the Champagne-Ardenne region, the British on Loos.

Field Marshal Sir John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, and Lt. Gen. Sir Douglas Haig, his First Army commander, faced less than ideal tactical conditions. The prospective battlefield—just north of Lens, a coal mining town in an industrialized area near the Belgian border in far northern France—was uniformly flat, dotted with mining villages, collieries and industrial buildings. Ubiquitous slag heaps comprised the only high ground, most of which the Germans had fortified.

Adding to the British commanders’ concerns were intelligence reports indicating the Germans were constructing robust second- and third-line defenses behind the front, which itself had been reinforced with machine-gun positions and wide belts of barbed wire. The Germans’ second line, on a reverse slope fronted by a 15-yard-deep wall of wire, lay just out of British artillery range, thus the guns would have to be redeployed forward to support any significant push. Further complicating matters was a shortage of artillery support, as the British had only 533 field guns to cover an 11,200-yard stretch of enemy positions.

French and Haig expressed their concerns to superiors and proposed an offensive farther north, which they argued would put them in better position to break the German lines, given their available men and supplies. But British Secretary of State for War Field Marshal Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener and the French high command overruled them. To compensate for the unfavorable terrain and the lack of munitions, commanders decided the British would, for the first time, use chlorine gas against enemy trenches prior to their attack.

Despite efforts to catch the enemy unawares, the British press carelessly broadcast the movements of infantry units, alerting the Germans to the likelihood of a forthcoming offensive in their sectors.

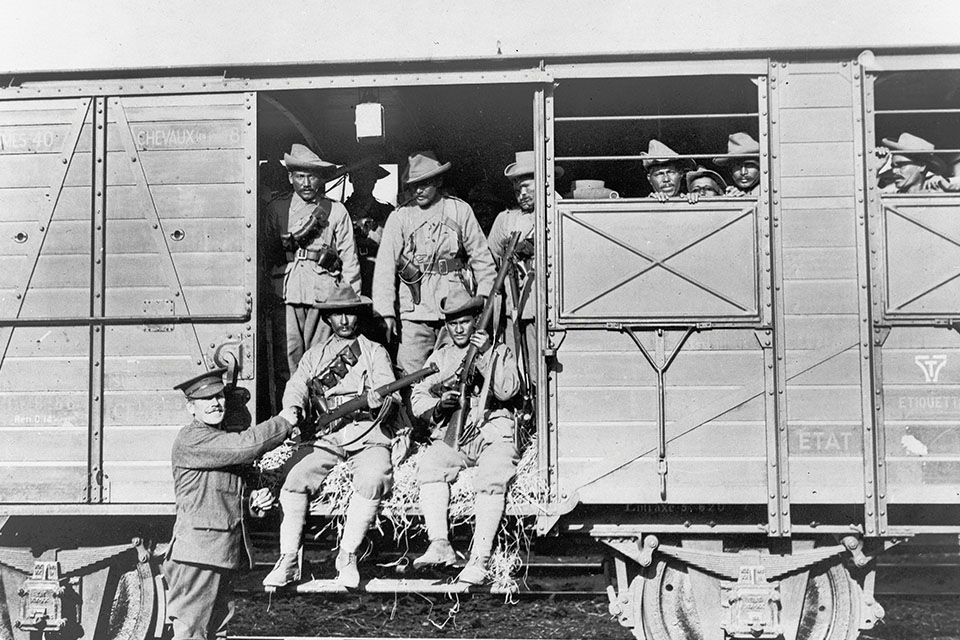

British forces marshaled for the operation included the 2nd Battalion, 8th Gurkha Rifles, one of five battalions in the Garhwal Brigade of the 7th (Meerut) Division of the Indian Corps. Having held the line in France in 1914, Indian units—including Gurkha battalions—would again have their skill and tenacity put to the test in the fall of 1915.

Loos would also be the first engagement for the British New Army. A new initiative for British armed forces, the all-volunteer force was Lord Kitchener’s brainchild, hence its nickname, “Kitchener’s Army.” Unfortunately, its men were poorly trained and ill-prepared for the rigors of war, particularly in comparison to regular British units already engaged along the Western Front.

Facing the British across no-man’s-land at Loos were elements of the German Sixth Army under Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria. Having withdrawn many units to the Eastern Front, the German high command relied on its Third and Sixth Armies—with seven divisions and three brigades in reserve—to cover the entire Western Front. In fact, German forces at Loos were spread thin and often outnumbered by their opponents—although the British did not realize it at the time.

the soldiers’ situational awareness. (Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Alamy Stock Photo)

In early September Lt. Gen. Sir Charles A. Anderson, commander of the 7th (Meerut) Division, was promoted to lead the Indian Corps, which then held almost 9,500 yards of the British line. To support the French attack in Champagne-Ardenne, the corps was tasked with attacking the high ground at Haut Pommereau before advancing toward German defenses to the south at La Bassée Canal.

On September 21 British artillery opened up on German positions, intending to continue the barrage unabated until the morning of the assault. Two days later, however, the weather soured, torrential rains hampering movement and visibility, flooding trenches and leaving some areas in a foot of standing water. British units nevertheless moved under the cover of darkness to their jumping-off areas and were in position by early morning September 25. The lead units were unaware the four-day preliminary bombardment had done little to damage German defenses.

Just before dawn on September 25, after checking weather reports, the British confirmed their intent to use chlorine gas, which they released minutes before 6 a.m., relying on the wind to carry the poisonous fumes across no-man’s-land into the enemy trenches. British units watched the gas bank up to 50 feet in the air, but the noxious cloud moved at a snail’s pace. In the interim many British soldiers took off their gas masks, which restricted their vision and did not seal properly. In some sectors the fickle wind blew the chlorine gas back into the British trenches, causing more casualties among the Allies than among the Germans.

Promptly at 6 a.m. the British hurled out smoke grenades and launched their attack. Forming on the left flank of the Garhwal Brigade, the first wave of men from 2/8th Gurkha Rifles clambered from their trenches and advanced into no-man’s-land. Undeterred by the preliminary artillery barrage, German forces lashed the advancing troops with effective machine-gun and artillery fire. Despite the stiff resistance, the first wave of 2/8th Gurkha Rifles managed to push as far as the German third line, their initial objective. Over the next two hours the battalion sent subsequent waves of troops to firm up Companies B and C, at the leading edge of the advance—but at a terrible cost. And as the Gurkhas pressed forward, they realized that the 2nd Leicestershire Regiment, which was to have protected their right flank, had been unable to get through the wire.

By 8:30 a.m. Captain Buckland of Company C found himself with only 150 men and two Lewis guns holding a position beyond the German third trench line. Enemy troops were probing the Gurkhas’ position to assess their strength.

When brigade headquarters ordered the 2/8th Gurkha Rifles’ senior officer to return to the British trenches and give a progress report, Buckland discovered he was the battalion’s only surviving officer. As he made his way to the rear, the Gurkhas continued to hold, despite having been further reduced to only 100 able troops. Buckland reported the precarious situation and requested reinforcements. Brigade ordered a reserve battalion to push forward to 2/8th Gurkha Rifles’ position, but the orders were slow to reach the appropriate officers.

Meanwhile, German units discovered the gap in the Gurkha right and moved up machine guns. German gunners poured enfilading fire into the Gurkhas’ flank as enemy assault parties tossed hand grenades into the British positions. In response Gurkha field officer Subedar Sarabjit Gurung led a detachment to engage the flanking enemy and disrupt the counterattacks. Though it fought fiercely, the outnumbered party was eventually overrun and killed.

That afternoon, as 2/8th Gurkha Rifles struggled to hold its exposed position in the face of mounting casualties, British commanders finally recognized the futility of continuing the advance. At 3:30 p.m. they ordered the remnants of the battalion to fall back and assume reserve positions. By nightfall 2/8th Gurkha Rifles—which had arrived in Loos with some 800 officers and men—was down to one officer and 49 other ranks, all of whom were wounded.

That British forces were ultimately able to break through German defenses and take Loos-en-Gohelle was the result not of superior firepower but due to the sheer number of troops thrown at the enemy lines. In the end, however, broken communication lines, a dearth of supplies and the late arrival of reserves made it all but impossible for the British to exploit their breakthrough.

According to Maj. Gen. Richard Hilton, who was a forward observation officer at Loos, all the British needed to achieve a definitive victory was “more artillery ammunition to blast those clearly located machine guns, and some fresh infantry.…But, alas, neither ammunition nor reinforcements were immediately available, and the great opportunity passed.”

Indeed, during the battle enemy commanders all but expected the British would achieve a decisive breakthrough. The German Sixth Army had few reserves available to plug holes the British punched into its lines, and enemy commanders feared a collapse of their defenses. But a lull in the fighting had allowed the German 117th Infantry Division to withdraw behind its second line and regroup, and on the night of September 25, as the surviving 2/8th Gurkha Rifles withdrew to the rear, the Germans fortified their defensive positions. The British continued their efforts to advance over the next two days, but the Germans stymied each attempt. By September 28 the British First Army was simply unable to launch more attacks, and commanders ordered the attacking units to fall back to their original lines. Fighting continued until October 8, with artillery duels and sporadic attacks and counterattacks, but the battle was effectively over.

More than 10,000 British troops took part in the initial attack on Loos on September 25. By the end of the 13-day battle British forces had suffered more than 61,000 casualties. Of those, some 15,800 were killed, and more than 2,000 officers were killed or wounded. The Germans, whose defensive fire was so effective in cutting down the attackers, later called the area Der Leichenfeld von Loos (“The Field of Corpses of Loos”).

In the end the engagement was a German victory. Their defenses held, and they forced the British to leave the field of battle. The British loss reflected a failure of leadership, as well as poor planning and execution. Commanders had not given proper regard to intelligence reports regarding German strength—and in some cases they’d even discarded the reports. The offensive was not carried out with the element of surprise, and both supply and communications problems plagued the assaulting units. Artillery strength was inadequate, and soldiers were sent into battle with inferior equipment. In the unkindest cut, the decision to pull back mess facilities to division headquarters meant that many men had gone into battle hungry.

Despite the courage and sacrifice of the British fighting men at Loos, including 2/8th Gurkha Rifles, the battle as planned and carried out was doomed from the start. Many men died due to the ineptitude of British leadership, and the war would drag on for another three long years.

U.S. Army veteran Dana Benner holds a degree in history and a master’s in heritage studies. He teaches history, political science and sociology at the university level. For further reading he recommends Gurkhas, by David Bolt; The Gurkhas, by Byron Farwell; and The First World War: A Complete History, by Martin Gilbert.