Men of the 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), had little time to rest in the early months of 1968 as enemy activities increased in northern South Vietnam. Throughout January, major elements of the 1st Cav, which had the most firepower and mobility of any division-sized unit in Vietnam, moved their base of operations northward from An Khe in the Central Highlands to Camp Evans, about 15 miles northwest of Hue to support Marine Corps operations in the region.

The move involved 20,000 men, 450 helicopters, artillery and supplies. Troops riding in huge truck convoys passing through Hue never suspected they would return in two short weeks to fight thousands of North Vietnamese Army regulars and Viet Cong forces during the communists’ Tet Offensive, launched Jan. 31, 1968, throughout South Vietnam.

The move involved 20,000 men, 450 helicopters, artillery and supplies. Troops riding in huge truck convoys passing through Hue never suspected they would return in two short weeks to fight thousands of North Vietnamese Army regulars and Viet Cong forces during the communists’ Tet Offensive, launched Jan. 31, 1968, throughout South Vietnam.

Hue was engulfed in some of Tet’s deadliest warfare. On Feb. 4, the 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, was airlifted to a site about 6 miles northwest of Hue. The battalion was ordered to work its way south and engage enemy units attempting to resupply, reinforce, enter or escape from the city’s northwest quadrant. Particularly intense combat occurred during a battle in a wooded area that housed the NVA’s central headquarters and supply base for the fighting in Hue. Both sides sustained heavy casualties, but cavalry troopers defeated the NVA defenders and had swept the encampment by Feb. 22.

The following day, the battalion was ambushed just outside Hue by enemy forces concealed in a cemetery.

On Feb. 25, the 7th Cavalry troopers reached the walls of Hue’s Citadel, a centuries-old fortress within the city. On April 1, they saddled-up for Operation Pegasus, a joint effort with other U.S. Army units and South Vietnamese troops to clear heavy concentrations of NVA soldiers surrounding the Marine base at Khe Sanh, which had been under siege since Jan. 21. The 2nd Battalion of the 7th Cavalry reached the base on April 8 and broke the siege.

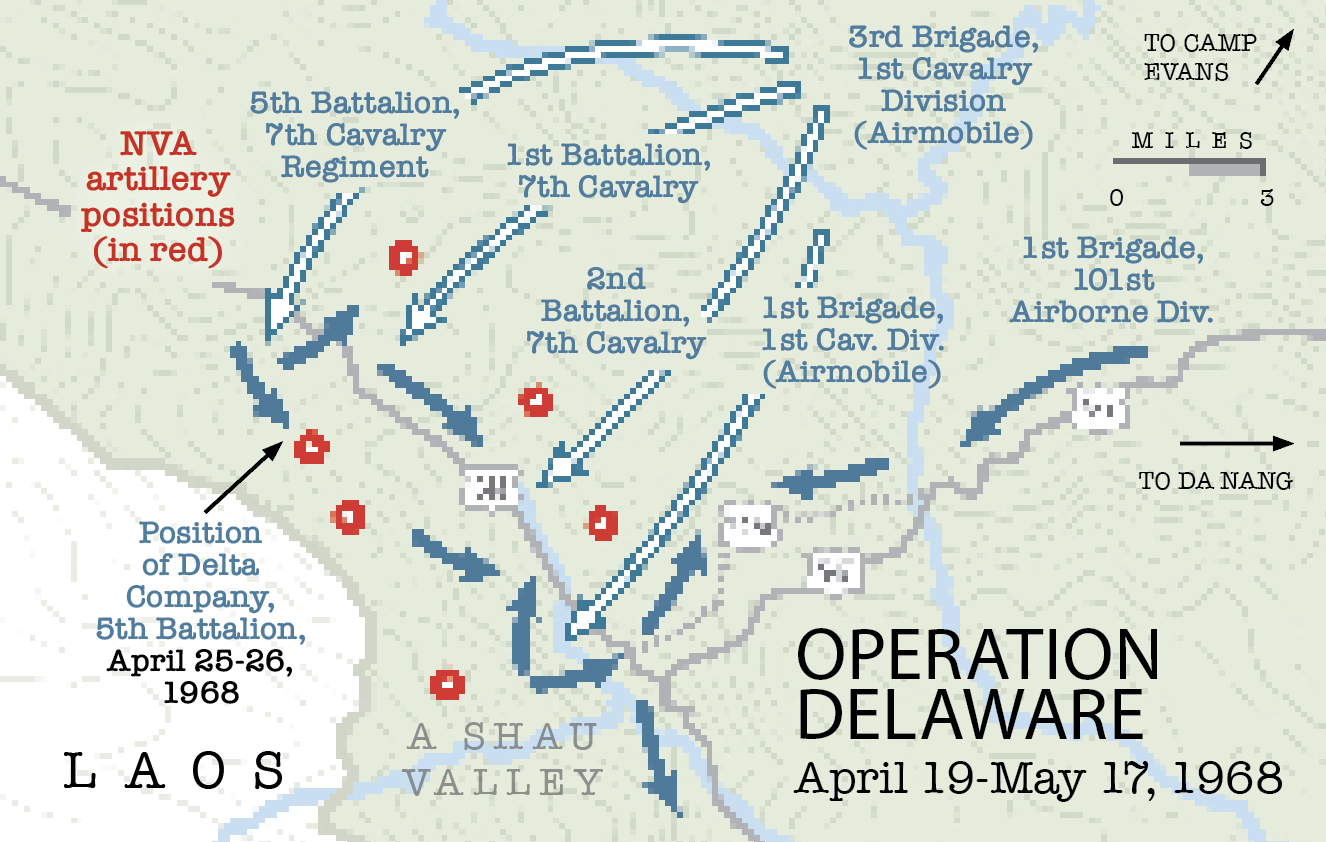

A few days later, the 5th Battalion was back in action. It departed on another complex air assault mission, Operation Delaware, initiated on April 19 in the cloud-shrouded A Shau Valley to strike North Vietnamese bases that had been used to launch the Tet attacks on Hue. Enemy troops in the valley, on the western edge of Vietnam, were less than 30 miles west of Hue. Operation Delaware was a combined airmobile and ground attack using elements of three divisions—the 1st Cavalry, the 101st Airborne and the South Vietnamese 1st Division.

A few days later, the 5th Battalion was back in action. It departed on another complex air assault mission, Operation Delaware, initiated on April 19 in the cloud-shrouded A Shau Valley to strike North Vietnamese bases that had been used to launch the Tet attacks on Hue. Enemy troops in the valley, on the western edge of Vietnam, were less than 30 miles west of Hue. Operation Delaware was a combined airmobile and ground attack using elements of three divisions—the 1st Cavalry, the 101st Airborne and the South Vietnamese 1st Division.

The A Shau Valley sits between two mountain ranges about 5,000 feet high with rugged, treacherous slopes at steep angles. North Vietnamese forces had been in control of the area since March 1966 when they overran a U.S. Special Forces camp at the valley’s southern end. No U.S. or South Vietnamese forces had penetrated the A Shau for two years. The NVA sanctuary was protected by dug-in ground forces and anti-aircraft weapons that included 12.7 mm heavy machine guns and 57 mm flak cannons.

Between April 14 and 19, more than 100 B-52 bomber sorties, 200 Air Force and Marine fighter sorties, and numerous flights of helicopters with aerial rocket artillery attacked targets in the valley in preparation for the main troop assault.

The 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment ofthe 1st Cav conducted extensive aerial reconnaissance missions to select flight routes, locate anti-aircraft and artillery weapons, and develop targets for airstrikes.

On April 19, UH-1 Huey helicopters airlifted companies of the 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, from Camp Evans. The plan called for the battalion to conduct an air assault onto Tiger Mountain, an ideal position to dominate enemy supply routes coming into the valley from Laos, about 10 miles to the west. Nearing the target zone, the mass of helicopters descended through dark clouds in a well-choreographed assault. Gunships led the way, followed by formations of Hueys carrying troops and supplies.

Suddenly, the world seemed to explode around the assaulting troops.

Bursts from intense anti-aircraft artillery and groundfire filled the sky, disrupting the paths of Huey pilots slipping under low clouds to spot the drop zones. Troops inside Hueys descending into a hot landing zone watched helplessly through open doorways as choppers around them were shot down and dropped to earth through the hail of tracers and exploding flak.

Alpha Company of the 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, was the first unit on the ground. The men took defensive positions on Landing Zone Tiger while an approaching second sortie of Hueys came under fire. One of the helicopters loaded with Delta Company men crash-landed within yards of Alpha Company’s position. Soldiers on the ground rushed from defensive positions to the wreck and helped with the evacuation. Two troopers onboard were killed by .51-caliber machine gun fire.

“The Huey was a great big target in the middle of my guys and continued to draw intense enemy fire,” said Alpha Company’s 1st Platoon leader, 1st Lt. Vince Laurich. After everyone was pulled from the wreck, Laurich ordered his men to remove the M60 machine guns from the helicopter. Then he commanded, “Push it off the hill!” Soon the mangled wreck was rolling down a steep slope.

Heavy anti-aircraft fire and worsening weather throughout the day prevented additional air assaults. The men already on the ground directed supporting airstrikes to known anti-aircraft artillery positions as they dug in for the night. By the end of the following day, the 1st Cav’s 3rd Brigade was firmly entrenched in the A Shau Valley with three infantry battalions in addition to supporting artillery.

As the week wore on, the 5th Battalion’s Delta Company, patrolling near LZ Tiger to clear the area of NVA soldiers, encountered heavy resistance seemingly everywhere along the makeshift roads the enemy had carved into the mountainsides. On April 24, during a mission to drive the North Vietnamese out of a saddle-like basin in the terrain below a road, Delta Company was stopped cold by a machine gunner in a cave and a well-camouflaged sniper positioned above the Americans.

“He was a pretty good sniper, knew his job and did it well,” said Delta Company 1st Lt. James M. “Mike” Sprayberry, the company’s executive officer. “He had the opportunity to kill more than a few of us but would only wound someone, knowing we’d have to use other men to pull them to safety.” In an effort to get beyond this dangerously effective NVA team, the troopers brought up a 90 mm recoilless rifle.

Just as they were about to load it, a sniper round shot from 200 yards away flew straight down the tube.

The cavalrymen had to find another way to reach the saddle area. A recommendation came from the command chopper flying above the action: Scale a steep, exposed basalt outcrop on the mountain’s north face. From there, move west behind the NVA sniper and machine gunner, then south toward the saddle. Because it was getting late, Capt. Frank Lambert, Delta Company’s commanding officer, ordered his troops to pull back for the night and make preparations for the climb the following day.

At first light on April 25, 1st Platoon’s men, led by 1st Lt. Dave Barber, got ready for the climb. Lambert joined them to help Barber, a new lieutenant, if necessary. Also joining the group were the captain’s headquarters radio operator, Spec. 4 George Mitchell, and an artillery forward observer with his radio man to direct artillery strikes if they came under attack. It took the 32 men nearly two hours to climb the near vertical escarpment and make their way around the mountain to avoid the NVA roadblock.

When 1st Platoon reached the saddle area and its two point men were about to cross the road, the platoon was immediately fired upon from seemingly all sides. Barber, his radio operator, Daniel Martin Kelley, and the two point men, David Scott and Hubia Guillory, were killed almost instantly in the ambush. The other troopers responded with heavy return fire as they scrambled to take up defensive positions.

During the fighting, the two sides drew closer and hurled grenades at each other. Eight men were seriously wounded and could not walk. Lambert had been shot, and as Norman “Doc” McBride worked under a hail of bullets to assist the captain, both were severely wounded by grenades landing nearby. (Lambert and McBride would recover from their wounds.) With the officers incapacitated, the platoon’s command fell to Staff Sgt. Billy Joe Baines, who ordered everyone to defend in place.

The other Delta Company platoons in the area heard gunfire from 1st Platoon’s direction, but the characteristics of the mountain basin muffled the small-arms fire, and as a result the sporadic shooting didn’t sound any different from the firing that had been coming from every direction for almost a week.

The reserve units learned of 1st Platoon’s short and fierce contact with the enemy only when a radio transmission by Mitchell—now handling both the platoon and headquarters communications—reported that Lambert was seriously wounded. The 2nd and 3rd platoons immediately mobilized, but their attempts to reach the isolated 1st Platoon were repelled by devastating fire from NVA bunkers that lined the road.

There wasn’t enough daylight remaining to safely send two platoons on the almost two-hour climb up the steep mountain, locate 1st Platoon’s position and then engage the enemy. Sprayberry, the Delta executive officer, decided to take a different route, one that depended on complete darkness for success. The lieutenant explained his plan: Locate enemy positions along the road, blast a hole through the NVA bunker line, find the stranded platoon and guide it to safety.

He asked for three or four volunteers. There was no shortage of those who wanted to go. Sprayberry settled on 10 men. He had seven lay back a little to ensure that the mission would continue if something happened to those in front.

Before heading out around 8 p.m., Sprayberry told his volunteers that once they reached the bunker line they needed to move unseen—camouflaged by the dark night, crawling if necessary along the dirt road that girdled the mountainside.

No noise. No quick movements. No return fire unless necessary.

Sprayberry reminded the men to be especially careful whenever beams of moonlight penetrated openings in the clouds because “visibility might improve to 5 or 6 feet for both sides.”

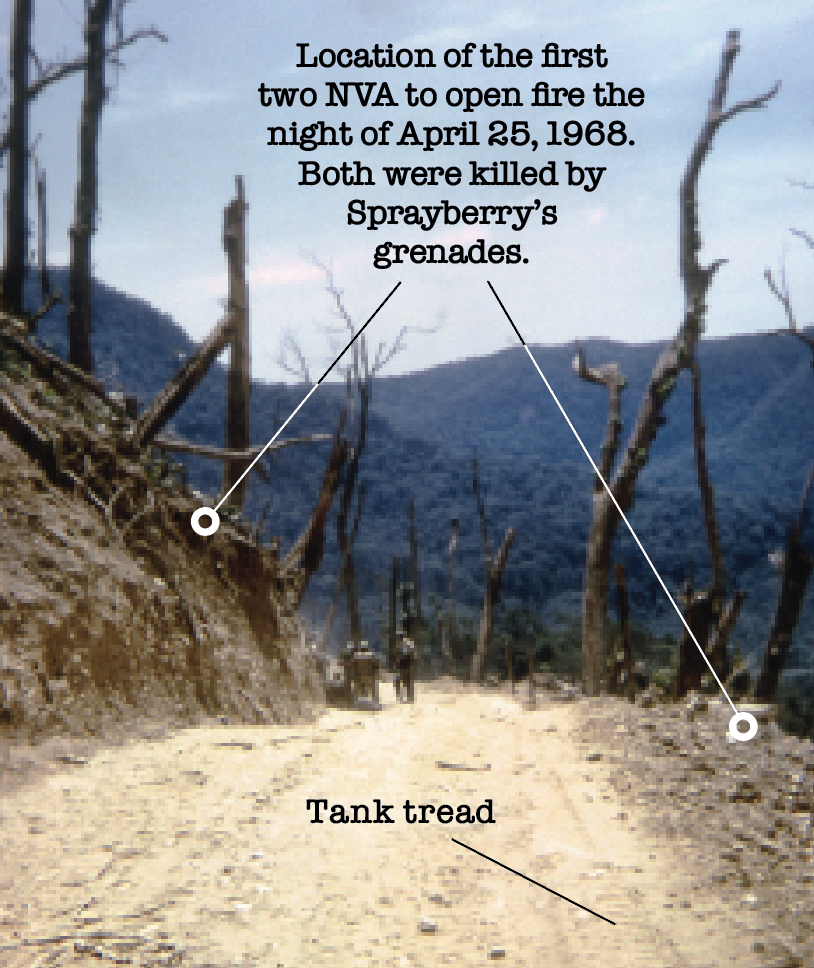

The 11 troopers covered a good distance unseen before receiving small-arms fire from two positions on each side of the road. Sprayberry moved his men back to protective cover and waited until silence returned. Now knowing where two enemy positions were, he crawled undetected within close range of a firing position dug into the upper right side of the roadway. He grabbed a grenade, pulled the pin, lobbed it uphill and instantly knew he had silenced the AK-47 rifle in the upper bunker. Quickly moving to his left, toward the opposite side of the road, he forced a grenade into a one-man enemy position that had given his patrol the most fire.

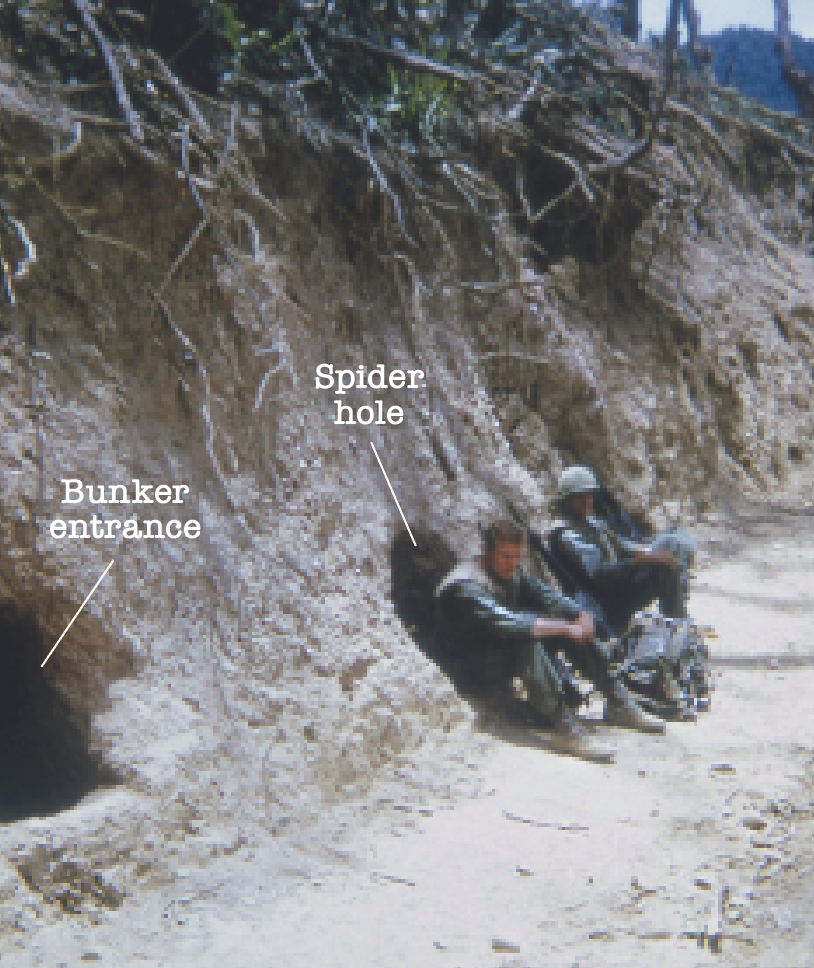

After the explosions, darkness returned, allowing Sprayberry to crawl back for more grenades. During that time, the enemy threw two grenades at his men from yet another position ahead of the cavalrymen. Sprayberry, again exposing himself, charged crouched over and stuffed a grenade into the hole, killing the bunker’s occupants. Knowing there were more NVA farther along the road, he positioned two men to cover him and crawled forward, staying tight to the embankment. The NVA in the bunkers above Sprayberry could not see him nor position their weapon to shoot accurately down at him. However, the lieutenant also was hampered by the darkness. He could only surmise the location of the enemy fire.

Sprayberry groped along the side of the road until he felt the edge of a hole. Sometimes he found a one-man “spider hole,” other times a two-man foxhole or an enclosed bunker. Each time he dropped, stuffed or threw a grenade. He then would hear a scrambling in the hole, a panicked sound or nothing. After each blast, when the dirt stopped raining down and the cover of darkness returned, Sprayberry moved forward.

The enlisted men trailing him checked each position to make sure the enemy threat was gone. At one point they received AK-47 rounds from a position they thought they had cleared, but it turned out to be a bunker interconnected with another fighting position. The second position was neutralized as well.

After Sprayberry had cut an opening through the NVA’s bunker line, he radioed Dan Nase, Delta Company’s second-most senior lieutenant and 3rd Platoon’s leader, who was in charge of the reserve platoons. Sprayberry told Nase to come forward, organize teams for litter bearers and place more men in defensive positions to secure the area.

Sprayberry moved slightly down into the saddle basin and sensed that 1st Platoon was close, so he radioed Baines, the sergeant now commanding the platoon, and told him to listen for a whistle. Based on the direction of the explosions Baines had heard earlier, he believed he knew where the rescue patrol was. The sergeant said he would go to Sprayberry and guide the rescuers to 1st Platoon. He said it would take about 15 minutes to reach the patrol.

After some time had passed with no contact, Sprayberry radioed Baines, telling him that he would whistle again and Baines should whistle back. This time Sprayberry heard a whistle reply. But instead of seeing Baines coming out the darkness, the rescuers on security detail spotted NVA soldiers who walked toward them and started talking. The enemy infantrymen seemingly mistook the whistling American for one of their own troops. The four intruders were killed at very close range. Sprayberry radioed for the rest of the platoons to move up with their litter teams.

As the busy executive officer was directing the rescue party details, an NVA soldier jumped from a concealed position and rushed through the darkness toward him.

Sprayberry heard the man coming and shot him point-blank with his .45-caliber pistol.

Not waiting for another surprise, Sprayberry dashed forward to eliminate the emplacement with a grenade.

About 3:30 a.m., with the immediate threat eliminated and all finally quiet, the lieutenant joined up with Baines and two other members of the stranded platoon. Sprayberry had them guide the litter teams, four men per stretcher, to 1st Platoon’s position. He ordered the rest of the rescue party to secure the area. The ambush had left 16 casualties: eight stretcher cases, four wounded (three needed assistance walking) and four dead.

Throughout the night Sprayberry’s men and the rescued troopers of 1st Platoon carried the 11 severely wounded men and Barber’s body back to the area where they had set up the previous day. Each grueling round trip took about 45 minutes across the steep slopes, made even more treacherous by the pre-assault bombing that had torn up the terrain. It took another 35 minutes to reach LZ Tiger for the air evacuations.

The troopers could hear NVA trucks and a tank traveling the roadway above them, possibly reinforcing the fighting positions along the road. The forward observer called for an artillery strike, hoping the coordinates he gave would block the advancing trucks. The troopers’ nerves were tested once more when they heard the truck engines stop and feared that enemy troops might be getting out and coming their way. After the artillery shelling ended, the trucks were restarted and headed back toward Laos—a big relief for the Delta Company men.

As the sky lightened on April 26, the rescue was almost complete. Everyone was out of the ambush site, except for a few wounded and the men securing the area. Looking around, Sprayberry noticed a machine gun emplacement being prepared uphill from their location. Making his way up to the gun, he dispatched it with a grenade before rejoining the last of the evacuees. All of the men finally reached safety around 8:30 in the morning.

Three of 1st Platoon’s dead could not be found in the dark and were left behind for retrieval in the morning. During that attempt, another trooper was wounded almost immediately. The NVA had reinforced the area during the night, and extraction was now impossible without additional losses.

On April 29, the 5th Battalion’s Bravo Company replaced Delta Company on the mission to block the road. On May 1, the crew of an OH-6 Cayuse, a light observation helicopter called the “Loach,” volunteered to search for the three Delta bodies, despite being told of the heavy enemy presence in the area.

Only minutes passed before the helicopter was shot down and the three crewmen were killed.

By the time the Bravo troopers could get close to the crash site, NVA soldiers had already crawled through the wreckage.

When Operation Delaware ended on May 17, the North Vietnamese had shot down not only the Loach but also a CH-54 Flying Crane cargo helicopter, four CH-47 Chinook transport helicopters and nearly two dozen Hueys. Many other helicopters were lost in accidents or severely damaged by ground fire.

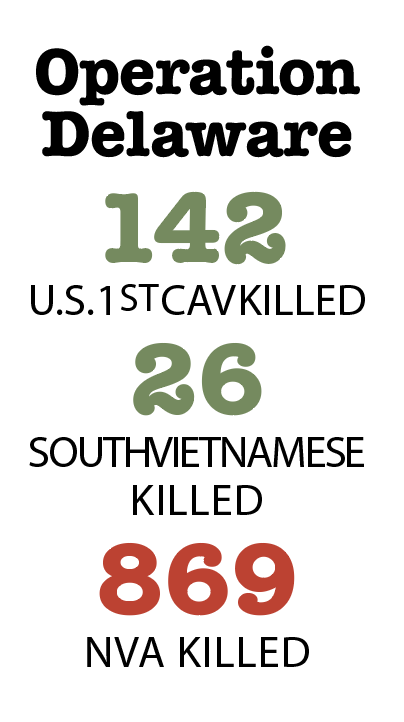

Overall, 1st Cav casualties for the operation were 142 killed, 530 wounded and 47 missing, mostly unrecovered air crews. South Vietnamese forces lost 26 killed. The enemy body count was 869 killed. U.S. and South Vietnamese forces captured huge caches of food, munitions and small arms, along with seven trucks, two bulldozers and one PT-76 light tank. Many transport trucks were destroyed.

Sprayberry was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to captain. He was credited with killing 12 enemy soldiers, eliminating two machine gun nests and destroying numerous bunkers. Silver Stars were presented to Baines and radio operator Mitchell, as well as to three other enlisted men on the rescue team.

In 1984, Sprayberry learned from radio operator Kelley’s father that the bodies of the three Delta Company troopers left on the battlefield and the three Loach helicopter crewmen had never been recovered. After attending a 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry, reunion in 2004, he took on a new mission: locating and recovering the remains of those six soldiers in the A Shau, as well as and the remains of two Delta men missing in action later in the war.

Sprayberry has returned to Vietnam seven times and had an eighth visit planned for August 2020, but it was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Guided by Sprayberry’s research, the U.S. and Vietnamese governments have jointly conducted five excavations at various sites. Sprayberry was recently notified that the Loach crash site was found.

While Sprayberry was in Vietnam in 2014, a meeting was arranged with a North Vietnamese colonel who served in the A Shau Valley. Col. Phuong said Sprayberry’s “cavalrymen must have been very well trained to be able to not only survive one of our specially dedicated ambush units, but also to escape at night over the terrible terrain.”

He suggested the probable location where the Americans could have been buried by the NVA soldiers. This new information may lead to a more successful excavation.

“The Vietnamese are very accepting of Americans,” Sprayberry said. “They are curious and very forgiving… and willing to help where and however they can. We had tried many times to locate a different helicopter crash site with no success until we met a local farmer who knew of its exact location… his backyard! Very little remained after 50 years of the environment taking its toll, but a future excavation may provide some closure. We’ll keep looking.” V

John Montalbano served with Alpha Company, 5th Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, from January through August 1968. He lives in Bolivia, North Carolina.

This article appeared in the October 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: