Wisconsin congressman was the reform movement’s most successful politician

DEJA VU

IN 2016, BERNIE SANDERS, a socialist-leaning Independent, threw a scare into Hillary Clinton on her way to coronation as the Democratic presidential nominee. Hillary prevailed, but the Vermont senator took a clutch of primaries. Two years later, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, self-described democratic socialist, unseated 10-term House incumbent and Democrat sachem Joe Crowley in the party’s primary in Queens, then cruised to an election-day victory.

Sanders is an old man, and an old story. Born in September 1941 in Brooklyn, New York, he has held office as a mayor, a congressman, or a U.S. senator almost continuously since 1981. By contrast Ocasio-Cortez, 29, is the youngest woman ever to serve in the House. Before her upset victory, she worked at a hip taqueria in Manhattan, where we knew each other to say hi.

Socialism is the flavor of the moment, a judo response to—or perhaps a parallax image of—Trumpian populism. However, socialists have long been an ingredient in the great stew of American third parties. At the end of the 19th century triumphant industrial capitalism became

the target of reformers and radicals from populists and progressives to anarchist assassins. Socialists, the leftmost reformers, sought nothing less than to transform the economic system. They also were the rightmost radicals, willing to work within the political system. In the presidential elections of 1912 and 1920, Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist Party’s presidential candidate, scored more than 900,000 votes—impressive, but nothing like successful; Debs tallied zero electoral votes. During the same period two socialists did win House seats. The

first, and longest-serving, was Victor Berger.

Berger, born into a German Jewish family in Transylvania in 1860, came to America at the end of the 1870s and found his way to Milwaukee. Wisconsin was a magnet for Germans; at the turn of the century they accounted for ten percent of the population there. Berger taught high school history and German, then switched to journalism—in late 1911 he founded the Milwaukee Leader, a daily newspaper—and politics. He flirted with radical factions—populism and Henry George’s single-tax theories—then set about building a Milwaukee-based Socialist Party political machine blending ideology and an emphasis on municipal infrastructure.

Berger believed, like Karl Marx, that the arc of capitalism bent inexorably toward oppression and class conflict, and that socialism was “the next phase of civilization, if civilization is to survive.” In the socialist phase, the government supposedly would own businesses and banks; farms, Berger thought, should stay in private hands. He respected the capitalist enemy’s acumen. A socialized United States Steel, he wrote, might still be run by its former CEO. “But we would not pay him $800,000 a year,” he added.

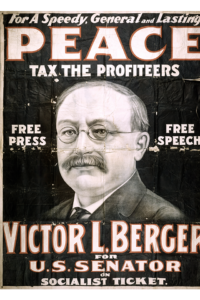

Berger parted from Marx in thinking that socialism could arrive peaceably, via democratic elections. The American reality of a widely dispersed franchise made a profound impression on him. John D. Rockefeller cast the same number of votes—one—as any of his employees. “This is the first instance in the history of the world that the oppressed class has virtually the same political basis as the ruling class,” Berger wrote. “It is foolish to expect results from riots and dynamite, from murderous attacks and conspiracies, in a country where we have the ballot.” In 1910, as if in fulfillment of his hopes, a slate of Milwaukee socialists won local office on a platform of municipal ownership of utilities. The same year, Wisconsin’s Milwaukee-centered Fifth District sent Berger to the U.S. House of Representatives.

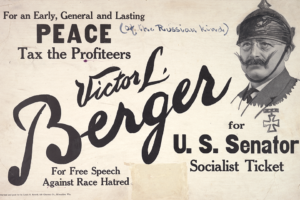

Berger’s first stint in Congress lasted only one term before world events changed the domestic political landscape. When Europe went to war in 1914, socialists wanted America to stay neutral—a stance rooted in the fact that, like Berger, many were culturally German. That affinity and their antiwar attitude made them pariahs in 1917, when America joined the fight on the side of the Allied Powers. The U.S. Post Office refused to deliver copies of the Leader, calling Berger’s paper disloyal. The December 1917 Bolshevik takeover of the Russian

Revolution offered a nightmare image of socialism. The Bolsheviks appalled Berger—he called communist Russia “a super state supported by terrorism”—but during the 1919-20 Red Scare suspicion transmogrified anyone on the left into a murderous demagogue.

Undaunted, Berger toiled on. In 1918 he won a second congressional race. Now his troubles began. In December 1918, the U.S. Justice Department tried Berger and four other socialists in Chicago before elaborately named Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis for conspiracy to hinder the war effort. Convicted, the five drew 20 years in prison. In May 1919, free on appeal, Berger appeared in the House to be sworn in. The House refused, asserting that he had given aid and comfort to the enemy, a violation of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, designed

to keep former Confederates from holding office. Only one member voted to admit the socialist. Wisconsin called a special election in December 1919 to fill Berger’s seat. He won handily; Fifth District voters did not like to see him being pushed around. Again, the House voted to keep him out; this time all of six congressmen spoke in his favor. “I do not share the views of Mr. Berger,” explained one, “but I am willing to meet his views in argument before the people rather than to say that we should deny him to opportunity to be heard.”

The next election, 1920, was the Harding landslide—bad news for any candidate lacking an R after his name. However, in 1922 Berger’s district voted him in once more, by which time the U.S. Supreme Court, on a technicality, had overturned those five convictions. A less feverish House calmly accepted Berger into the ranks. He served until 1928. He died the year after he left Congress, run over by a trolley on the streets of the city he loved.

Berger showed he could win elections, and his legal travails and vindication made a stirring story. Did he bring America nearer the “next phase of civilization”? Socialists to Berger’s left decried his moderation, branding it “slowcialism” or, mocking his focus on urban mechanics, “sewer socialism.” The academic Roderick Nash argued that Berger was too successful for his own good, proving only that socialism in America succeeded when it was “susceptible to absorption and dilution in the American ethos.” The mainstream has adopted Socialist Party platform plans piecemeal: public utilities, a graduated income tax, federal health insurance in the form of Obamacare. Public ownership of banks and transportation remain a way off, though the TARP bailout and Amtrak could be seen as steps in those directions.

The nation’s first 80 years saw major parties come and go—Federalists and Whigs, for instance, plus dramatic flare-ups like the Anti-Masons and the Know-Nothings—before the Civil War baptized the two-party system of Democrats and Republicans in blood. Subsequent political storms have beaten in vain against that plinth. New parties’ function for 150 years has been to bring to national notice issues like Prohibition and programs like populism or socialism to be absorbed and if necessary, discarded by donkeys and elephants. Hence Bernie Sanders, though mostly maintaining his label as an Independent, caucusing in Congress with the Democrats and running in 2016 in Democratic primaries, and Ocasio-Cortez making her maiden run as a Democrat.