Three generations of veteran relatives are soon to be buried together at the Great Lakes Cemetery in Holly, Michigan.

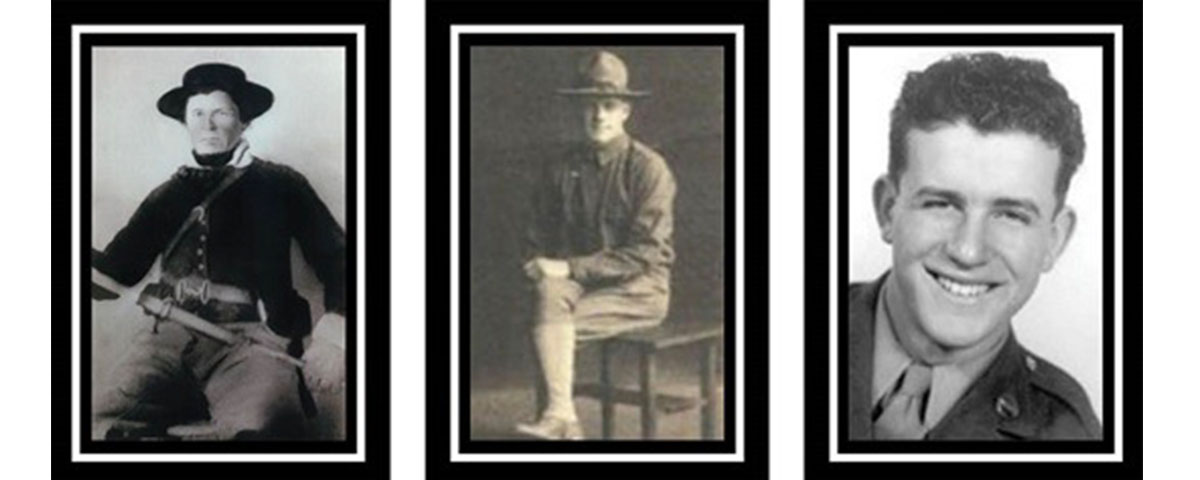

Through the support of a Go Fund Me page, Dr. Robert Armstead has embarked on a year-long campaign to bring his great-great grandfather Peter Armstead, a Civil War soldier; his great uncle Earl Armstead, a World War I veteran; and his father, Robert Armstead, a World War II veteran, to their final resting place, side-by-side.

After witnessing Peter Armstead’s deteriorating headstone at New River Cemetery, Port Austin, Michigan, Armstead became determined to have his family looked after in the veteran’s national cemetery in Michigan.

“A veteran is entitled to be buried free of charge at a national veteran’s cemetery. And with that, their gravesites are taken care of for eternity. That was key for me… I wanted them to be taken care of,” Armstead told HistoryNet.

And while the funeral, to take place on August 26, has turned private owing to Covid-19 concerns, Armstead is adamant that the re-interment of his family members highlights the service and sacrifice of all veterans. “I wanted to go public (about the burial) because there has been a lack of patriotism in this country,” Armstead told MLive.

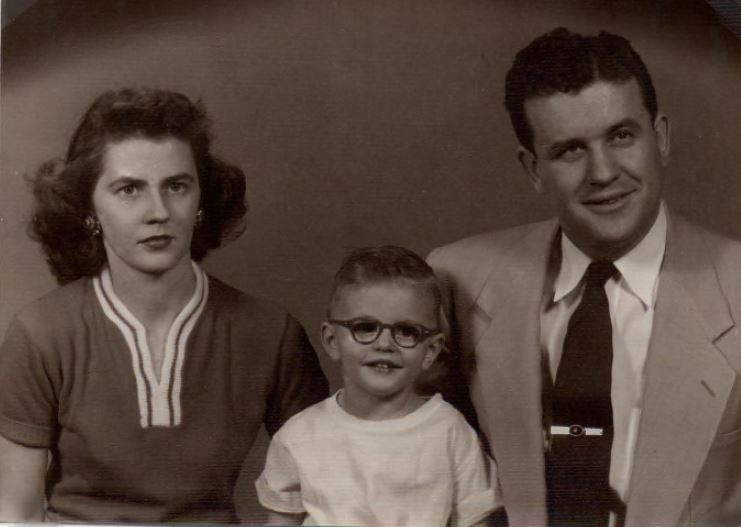

According to Armstead, all three men suffered greatly with PTSD, although it wasn’t recognized at the time. “My dad’s saying was ‘I survived the war, I can survive anything in life,’ ” but at times “he would just shut down and it would affect me. It affected the entire family.”

Drafted into the Army in 1944, Armstead was assigned to Company B of the 804th Tank Destroyer Battalion and saw action in the Po Valley Offensive in Italy, one of the last drives to trap the fleeing German and Italian soldiers.

Serving for 22 months, Armstead, promoted to sergeant, was awarded the American Theater Ribbon, Good Conduct Medal, Victory Medal World War II, and EAME Theater Ribbon—but at a cost. “Obviously I didn’t know,” Armstead told HistoryNet, “but my grandmother told he came back a changed man.”

Armstead’s great uncle, Earl Armstead, saw combat in World War I and suffered from undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I tried to talk about it with him when I was older, but he just wouldn’t talk about it. The most I got from him was that he went behind enemy lines and blew up bridges. He’d just go into a daze,” said Armstead.

“We would be eating at the kitchen table and he’d just start crying. I would be bewildered, and he’d just walk out of the room. I didn’t realize that it was his PTSD kicking in.”

Shell shock or combat fatigue was a new concept at the advent of the 20th century, and for Civil War veterans like Armstead’s great-great grandfather, there wasn’t even a definition yet for his trauma.

Enlisting in Company H, Third Regiment, Michigan Cavalry on September 25, 1861, Peter Armstead was captured less than a year later at Rienzi, Mississippi. Captured and placed in a prisoner of war camp, Armstead survived solely by eating tobacco and drinking water.

In one of the cruel ironies of war, Armstead later contracted lip cancer from the tobacco and was discharged in 1864 for war-related disabilities. He died at the age of 49.

Devoted to his father and his family’s legacy of service, Armstead spent the last several years of his father’s life taking care of the veteran around the clock.

When Armstead passed away in 2018 at the age of 92, it was his wish to be buried next to Earl, who was like a father to him.

And on August 26th, the two veterans will once again lie peacefully at rest alongside Peter—the gravesites remaining a standing testament to family, service, sacrifice, and country.