One of the first carrier-based aircraft featured a space-saving folding fuselage and inflatable flotation devices in the event the pilot had to ditch.

Carrier-based airplanes have been a breed apart since their conception. Operating from the deck of a ship imposes special requirements on aircraft design and construction. A case in point is the Parnall Panther, one of the very first airplanes specifically designed to take off from and land on the deck of an aircraft carrier at sea.

William Parnall established Parnall Ltd. in 1820 in Bristol, England, for the manufacture of weights and measures, later expanding into shop fittings. By August 1914 the company was under the direction of his descendant George Parnall, a visionary who was interested in aviation. During World War I Parnall’s firm was subcontracted to manufacture more than 600 aircraft, including the Avro 504K, Fairey Hamble Baby and various Short floatplanes. In 1916 the company produced its first original aircraft, the Parnall Scout, a large single-engine single-seater intended as a Zeppelin interceptor. It proved too fragile and overweight and was quickly abandoned.

In 1917 Parnall hired an experienced aircraft designer, Harold Bolas, who had formerly worked for the Royal Aircraft Factory before becoming deputy chief designer at the Royal Navy’s Air Department. Bolas’ Panther was a two-seat spotter-reconnaissance plane designed to operate from an aircraft carrier—a ship that did not really exist at the time. Although numerous seaplane carriers were operational and landplanes had been successfully launched from their decks, the only ship then capable of launching and recovering wheeled airplanes, HMS Furious, was hindered by the turbulence generated by its midships superstructure and funnels. The Panther’s intended vessel, Argus, featured a continuous, unobstructed flight deck. It was under construction on an uncompleted hull originally meant for an Italian passenger liner, but by the time the carrier was commissioned in September 1918 it was too late to see combat.

In WWI’s immediate aftermath, the big guns of the battleships were still regarded as the principal arbiters of naval power. The main role of airplanes like the Panther was to locate the enemy fleet and then direct the battleship’s salvos.

Superficially typical of its time, the Panther was a fairly compact single-bay biplane with a wingspan of 29 feet 6 inches and a length of 24 feet 11 inches. Fully loaded it weighed 2,595 pounds. Although armament was originally one forward-firing .303-caliber Vickers machine gun and a single flexible Lewis machine gun in the rear cockpit, on production aircraft the forward gun was dispensed with in order to save weight. Power was provided by a 230-hp Bentley BR-2 rotary engine, the same engine used on the Sopwith Snipe, the first fighter to be ordered in quantity by the Royal Air Force. The Panther’s maximum speed was 108 mph and its endurance was 4½ hours.

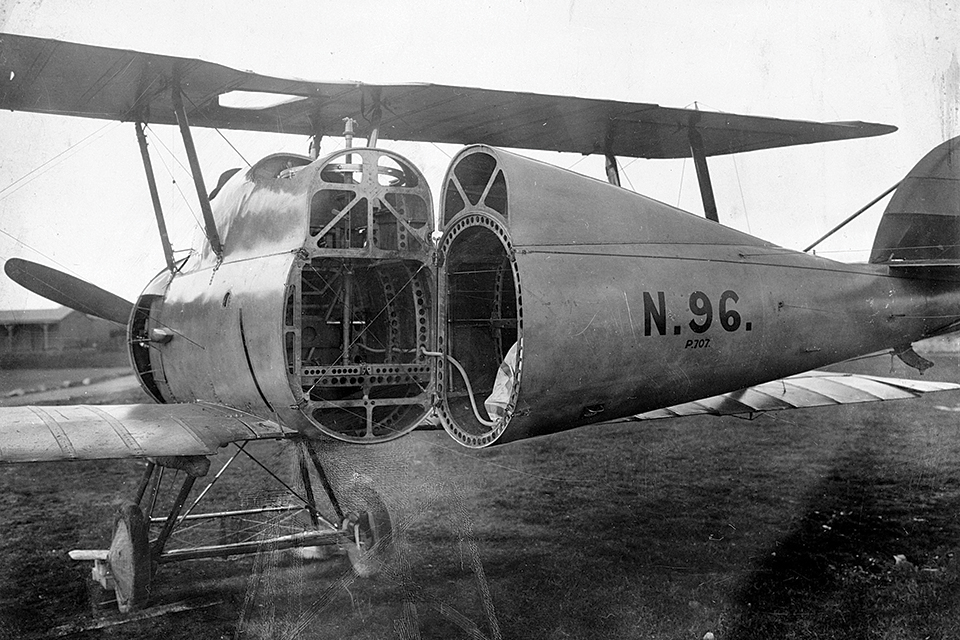

Bolas added some unusual naval features to the Panther’s basic biplane formula. The fuselage was humped to raise the pilot’s cockpit above the engine level and afford him a better view while landing on the flight deck. The wooden monocoque fuselage was fitted with watertight bulkheads to help keep the airplane afloat in case the pilot had to ditch in the sea. For additional buoyancy it had a pair of flotation bags fitted to the landing gear legs beneath the wing roots, along with a third stowed within the rear fuselage, all inflated by compressed CO2 bottles. A hydrovane was also installed ahead of the landing gear struts to prevent the Panther from nosing over while ditching.

Perhaps the Panther’s most unusual feature was its hinged fuselage, which could be folded 90 degrees to the right, just behind the observer’s cockpit, to save space during stowage. The concept had been pioneered on the Sopwith Baby and was a feature of the Hamble Baby that Parnall built under license. Later carrier-based airplanes employed folding wings for the same purpose. Also unlike later carrier planes, the Panther did not have a tail hook, simply because no such arresting system had yet been developed.

Following evaluation during 1918, Parnall received an order for 300 Panthers. With the cessation of hostilities, however, the order was cut back to 150, leading to a falling-out between Parnall and the Royal Navy. As a result, the production order was transferred to the Bristol Aeroplane Company, which completed delivery during 1919 and 1920.

Panthers were among the initial complement aboard Argus as well as Hermes, commissioned in 1924. As with all technological innovations, both the ships and their aircraft experienced teething troubles. For example, the system of arresting wires developed by the Royal Navy shortly after the war, consisting of a set of longitudinal cables to be snagged by hooks on the aircraft, proved inadequate and caused many landing accidents.

The Panthers themselves also demonstrated operational shortcomings. While a hinged flap at the rear of the upper wing center section afforded entry and exit from the rear cockpit, the only way into or out of the pilot’s cockpit was through a narrow opening in the center section. That was awkward for the pilot while on the rolling deck of a ship and dangerous in an emergency ditching. The Bentley rotary engine proved difficult to start, unreliable and insufficiently powerful. Moreover, it soon became apparent that the Royal Navy required a larger, heavier and more powerful aircraft with longer range, room for a crew of three and space for navigation and radio equipment. By 1926 the last Panthers were replaced.

In its heyday the Panther attracted the attention of other naval-minded countries. In 1921 Japan bought 12 Panthers to evaluate for possible use on its first carrier, IJN Hōshō, which would be commissioned in 1922. The U.S. Navy also purchased two Panthers in 1921 for its first carrier, USS Langley, undergoing conversion from the collier Jupiter. Two Panthers were also purchased by Spain and one is said to have been dispatched to Africa in 1922.

Parnall continued to develop aircraft up to 1939, including several interesting designs, but none were produced in significant quantities. During World War II it built Frazer-Nash gun turrets for British bombers, and after the conflict it made washing machines and stoves. Still in business today, Parnall Ltd. is currently building a non-flying Panther replica.

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!