When former Union officer Elijah Fearing Hobart booked his cruise on the canal boat Flying Cloud, he was hoping for a few hours of relaxation and respite from the war. His cruise ran directly into the Calico Raid, and he was shot dead.

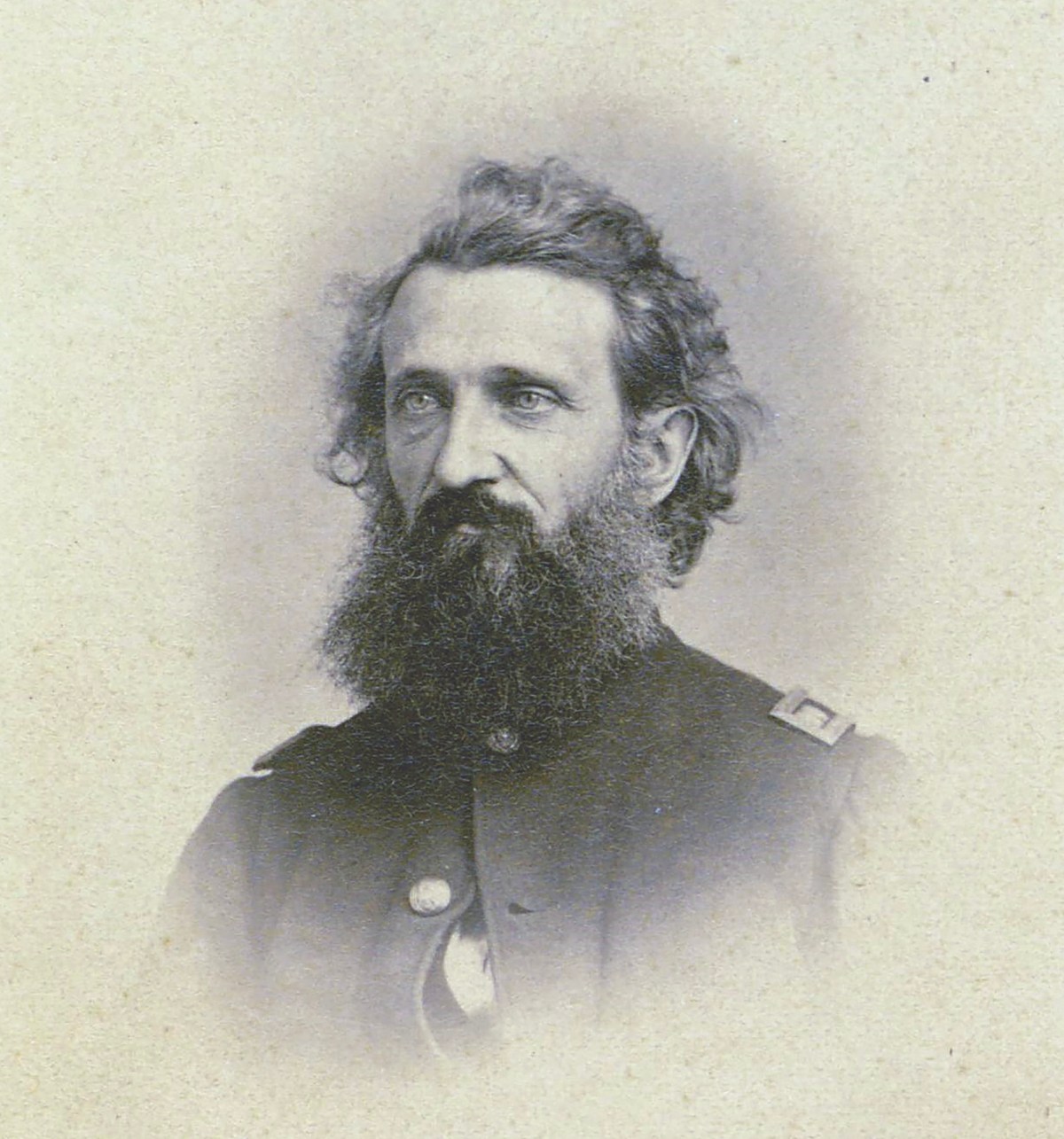

Hobart was born in 1821 at Hingham on the Massachusetts coast, and traced his lineage back to the Mayflower’s landing at Plymouth Rock. Both of his grandfathers had fought in the Revolutionary War. He moved to Boston at age 15 to learn the engraving trade. Becoming a proficient engraver, he moved to Albany, N.Y., and worked engraving bank notes. In the late summer of 1861 he determined to recruit a company for Federal service and promised his enlistees that the company was bound for the famed Berdan’s Sharpshooters and that the men would receive Sharps breechloading rifles. He was elected captain of the company. New York Governor Edwin Morgan, however, declined to assign the men to sharpshooter service, instead designating them as Company B of the 93rd New York Infantry.

The enlisted men of the company felt they had been duped. The promises of Sharps rifles went unrealized, and following their arrival on the Virginia Peninsula in March 1862, the company laid down their arms in protest. The men were placed under guard while Captain Hobart and the lieutenant colonel commanding the regiment, Benjamin C. Butler, were placed under arrest. With the Federal army soon on the move toward Williamsburg, Va., the company elected to pick up their arms and both Hobart and Butler were released.

By the middle of May 1862, the regiment was detailed for provost guard duty at White House Landing, Va., when Hobart was detailed to transfer Confederate prisoners to Fort Monroe. On reaching his destination, he was there ordered to transfer the prisoners further to Fort Delaware, located on Pea Patch Island south of Wilmington, Del. After completing the transfer Hobart returned to the regiment to find he had been considered absent without leave and was again arrested. Though eventually released from confinement, Hobart learned from a July 18, 1862, issue of the New York Herald that he had been dismissed from the service.

“The blow came like a flash of lightning from a clear sky,” recalled a friend. Two days later Hobart received official communication regarding his dismissal and departed for Washington, D.C., to clear his name. “When he left the regiment,” recalled one comrade, “it lost one of its best and bravest officers.” After months of unsuccessfully requesting a hearing, Hobart acquiesced and returned to his prewar engraving profession. He took a job at the Treasury Department where he oversaw the engraving of fractional currency.

In the summer of 1864 a party of Treasury Department employees, Hobart included, arranged for a Fourth of July pleasure trip from Georgetown to Harpers Ferry on the C&O Canal. The boat for the trip, a steam packet dubbed the Flying Cloud, was described as “a handsome specimen…a beautiful boat” when it had launched in 1858 as a light freight and passenger canal boat. The Flying Cloud catered to pleasure excursions, running the canal between Georgetown and Point of Rocks at a clip of eight miles an hour, three times a week since September 1862. The boat had even come under fire from a Confederate battery at Ball’s Bluff on September 4, 1862, escaping without injury.

While Hobart and his friends were likely following the developments of Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s advance down the Shenandoah Valley, they were unaware their pleasure trip would lead them into danger. Early had his sights set on Washington, but he first needed to clear the Harpers Ferry garrison standing in his way. After skirmishing at Bolivar Heights and Camp Hill, the Federal garrison abandoned Harpers Ferry and dug in on Maryland Heights, removing a pontoon bridge and burning the Baltimore & Ohio Bridge behind them. Harpers Ferry was once again a war zone.

Operating in conjunction with Early’s advance, Colonel John Singleton Mosby and his partisan command determined to attack a small Federal garrison at Point of Rocks, Md., located on the Potomac River downstream from Harpers Ferry. If successful at Point of Rocks, Mosby could sever the telegraph, rail, and canal line between Maryland Heights and Washington.

The Flying Cloud passed a leisurely trip up the canal on July 4, safely passing Point of Rocks before ultimately reversing course prior to reaching Harpers Ferry, the echoes of rifle and artillery fire alerting the passengers and crew to the fighting ahead involving Jubal Early.

Mosby, with 250 men and one howitzer had reached Point of Rocks after the Flying Cloud had passed. From the Virginia shore his men drew fire from an equal-sized garrison of Federal troops belonging to the Loudoun Cavalry and First Potomac Home Brigade. Once the Confederates crossed to the Maryland side of the river, the Federal garrison quickly retreated towards Frederick, leaving Point of Rocks to Mosby’s fate.

Flying Cloud approached Lock 28 on the C&O as Mosby’s assault was underway. Mosby’s artillery, unsure of the crew or contents on the boat, trained their shots on the boat. The lockkeeper had either abandoned the lock or refused to operate it, meaning Flying Cloud was a sitting duck, literally dead in the water. Some of the party jumped from the boat and attempted to force open the lock doors while others retreated into the woods.

The boat’s impasse at the lock cost Hobart his life. Accounts of Hobart’s last moments vary. One account claims that he refused to leave the boat or be taken prisoner and was summarily shot by Mosby’s men. Another account claims that Hobart turned to a fellow passenger saying, “They have our range—jump, and I will follow,” but was shot from behind by a squad of Mosby’s men who had circled through the woods. Both accounts indicate he did not linger after the fatal shot. Hobart was not the only noncombatant casualty that day, as a stray shot killed local resident Hester Ellen Fisher, only 18 years old, while she observed the fighting from her front porch.

Mosby’s men liberated a supply of food, whiskey, and cigars from the Flying Cloud before setting the boat aflame. The rangers likewise cut the telegraph lines, fired on an approaching train, damaged the B&O tracks, and burned four other canal boats and the abandoned Federal camp.

Elijah Hobart’s body was first interred nearby, but within days at the request of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton the body was disinterred and removed to his hometown of Hingham.

In the years following the war, Hobart’s comrades from the 93rd New York would petition that his dismissal from the service better reflect an honorable discharge. He was remembered in their regimental history as “…a noble man, of many disappointments and trials, one who, if an uncompromising opponent, was a warm, unhesitating, uncalculating friend; who considered no sacrifice too great for one he loved, and who was generous, even to his enemies.” ✯

Jon-Erik Gilot has worked in the fields of archives and preservation for more than 15 years. He is a contributing author at the Emerging Civil War blog and his first book, a history and tour guide of John Brown’s raid co-authored with Kevin Pawlak, is due out next year.