On Memorial Day 1889, Civil War veterans gathered with civilians at the Allegheny Cemetery in Lawrenceville, Pa., just east of Pittsburgh, to reminisce and remember those lost not only on the battlefield but on the home front as well. Notably, Lawrenceville was the site of the war’s largest industrial and home-front disaster—the Allegheny Arsenal explosion of September 17, 1862. A simple obelisk had been placed near the southern end of the cemetery to memorialize that day’s horrific events. Below it lay the unidentified remains of about 40 of the 78 workers who had perished in the blast and subsequent fire. Family members, friends, and survivors solemnly laid flowers about the site and listened to a powerful eulogy delivered by the Rev. Richard Lea, a local pastor who had experienced the tragedy firsthand.

Although overshadowed in national periodicals by the Battle of Antietam, occurring the same day, the arsenal accident continued to resonate heavily with the local community for more than a century. On September 18, 1862, John Symington, the arsenal’s colonel of ordnance, noted that “the whole proceeds of the day…exploded, amounting to about 125,000 of .71 and .54 [caliber] small arm cartridges, and 175 rounds of field ammunition assorted for 12-pounder and 10-pounder Parrott guns.” Though Lawrenceville was far from the battlefields, the thought of that day conjured up warlike memories for survivors and witnesses alike. As military veterans honored their fallen on battlefields postwar, Lawrenceville’s civilians likewise paid their respects at the hallowed ground of the arsenal.

A native of Coventry, England, Lea had served as a pastor in the Pittsburgh area for at least 55 years—a majority of that period at the Lawrenceville Presbyterian Church, which stood less than a block away from the arsenal grounds. He was a revered member of the community who oversaw a large congregation and was regarded for his compassion. Lea, in fact, had borne witness to warlike imagery at the arsenal. One of the first to arrive in the wake of the explosion, after the first of three blasts shattered most of his church’s windows about 2 p.m., the reverend scaled the arsenal wall and began rendering aid to the wounded and providing comfort to the dying. Lea soon discovered that three of his parishioners were among the departed.

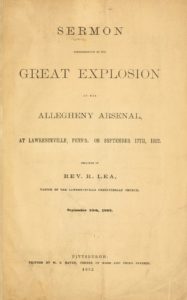

On September 28, 1862, Lea delivered a stirring sermon to his congregation chronicling the horrors he had witnessed. The following account illustrates his experiences in graphic detail.

[hr]

“The uncertainty of human life was never more strikingly shown in this community than upon the memorable 17th day of September, 1862. The morning was calm and beautiful, and until noon nothing unusual occurred at the Allegheny Arsenal. It was pay day, and the noble Union girls, who had toiled all the month, were rejoicing over the reception of the fruit of their labor. The shop had been swept, and among the leavings, some loose powder was scattered over the stony road winding around the beautiful grounds. A wagon was passing, when either the iron of the wheel or horse’s shoe struck fire. In an instant a terrific explosion was heard, shaking the earth, and inflicting injury upon the surrounding buildings. Amidst a dense column of smoke, and a bright sheet of flame, were seen fragments of the building, mixed with portions of the human frame, rising high into the atmosphere, and then falling in a horrid shower all around.

Some panic-stricken persons shouted: ‘The magazine is on fire!’ Repeated explosions, and the wild confusion, seemed to confirm the awful report. In this dreadful stage some were thoughtful and calm—others prayed and wept, while many rushed, horror-stricken, they knew not whither. A few stopped not until they were miles from the scene of danger. Several were picked up insensible, and when consciousness returned, were unable to tell whither they were going or wherefore they had fled.

But amidst all this dismay and fearful consternation and apprehension of still worse to come, when the magazine should explode, there were many who entered the gates and climbed the walls, determined to aid, or die in the attempt. The doors of the large building near the entrance to the park were closed, and the frantic girls, supposing themselves confined for certain burning, without hope of escape, pushed and trod upon each other, screaming and leaping from the windows, seeking avenues of escape, or sitting down in dumb despair. Strange that more were not mangled here; as it was, serious injuries were inflicted, and terror was added to the scene.

But the central terror was the burning laboratory. Here one hundred and fifty-six girls were ready to resume their labors, and were, almost without a moment’s warning, wrapped in flames, or violently thrown from the building; a few ran, or were blown out into the yard, and escaped; some were rescued by the daring of friends, but the majority met death instantaneously—perhaps hardly knowing the cause of their death. The fire was so fierce, the sulphur so suffocating, that an instant was sufficient to extinguish all sensibility. Some were dragged from a mass of ruins who had died in each other’s arms; some were rescued who would recover. A few escaped without assistance, who will die of their injuries. Some could merely mention their names, or call for a priest, or for water, or for prayer, but all upon the ground were naked, blackened with powder, roasted, somewhat bloody, and with many the resemblance to the human form was completely lost.

Nothing but masses of flesh and charred bones remaining of what, such a short time before, was life and beauty. In most instances the skulls of those taken out dead were fearfully cracked. The victims lay about upon boards and shutters, amidst a horror-stricken crowd, the trees above holding fragments of female attire, mournfully waving to and fro over their former owners. It may be possible that a few were entirely consumed—not a distinguishable relic being left to testify respecting their untimely end. The building was utterly consumed, and the ashes were carefully raked for every vestige of its former occupants. The calamity was so sudden, so crushing, so wide-spread in its results, and the horrors so varied, that the large crowd which assembled seemed overwhelmed—the usual signs of sharp woe giving way to solemn remarks or the stillness of stupefaction.

When the fire was utterly subdued, the noise, the turmoil of the scene was over, then came the terrible, orderly process of identification and burial. A hand was identified outside the grounds by a ring upon the finger, a leg by a shoe upon the foot ; but in neither case was the former owner of the fragments found. A parent would bend over some blackened corpse, examining minutely form, hair, any relic of dress, and then drop down silently if nothing was discovered, or shriek wildly if something certainly proved that these changed bodies were really the remains of their loved ones.

Parts of two days these affecting scenes were constantly witnessed, but after all the efforts of deeply interested friends and spectators, about forty were unrecognized. There they lay, subject to the minutest scrutiny, yet neither sister nor mother could tell which of these they had watched over from infancy, and had so lately parted from, with the farewell kiss, for the day, they supposed; but alas! it was a final adieu. The immense throng of people was a distinctive feature of the scene. Cars and all kinds of vehicles, loaded to their utmost capacity, and the sidewalks, crowded with passers to and fro, led by every imaginable impulse, irresistibly drawn to the gates within which such a fearful tragedy had been acted. The crowd was immense on Wednesday and Thursday, and for days continued lessening gradually, as though unwilling or unable altogether to escape at once from the terrible fascination of the place.

The Government provided plain black coffins for the un-distinguished remains. The Allegheny Cemetery donated a lot suitable for the internment. The bodies were gradually re-moved to their place of repose, and about three o’clock on the 18th, the mighty mass of human beings moved, accompanying the last body from the Arsenal to the grave. The mayors of both cities were there; the council and clergy of Lawrenceville; a number of carriages, and a countless multitude of all ages and classes walked in mournful order to the place.

It was a large, deep pit—unlike, in its vastness, any other grave; planks were laid across and from these, coffin after coffin was lowered to men below, who placed thirty-nine coffins side by side, filled by those whom no one could recognize, but whom the whole community adopted and honored as sisters and brethren who fell at the post of duty. After the last coffin had been lowered, the friends of the deceased were invited to the front rank, upon the margin of the grave, opposite the officiating clergy. Brother Millar, of the Methodist Church, offered a prayer; Dr. Gracey read a portion of the book of Job; Reverend Andrews, pastor of the United Presbyterian Church, prayed; Reverend Lea, pastor of the Lawrenceville Presbyterian Church, made an address; and Reverend Edmonds, of the Episcopal Church, pronounced the benediction. Blather Gibbs, of the Catholic Church, signified his intention of being present, but was officiating at the same time over the remains of other victims in St. Mary’s Cemetery, immediately adjoining. The dust was committed to dust until the morning of the resurrection, and a committee has been appointed to procure funds to erect a suitable monument to their memory.

Among these unrecognized remains were some dear to their own churches for their piety and virtues. They will be missed from the house of God. Three were members of this church—two by baptism and one by profession. Mr. David Gilleland lately came among us—a man of warm, modest piety, who loved the house of God—who was almost always at the prayer meeting, and who loved to be a spectator, even when not teaching in the Sunday School. He will never lead our singing again, but we trust that ere now his voice has been heard among those who sing around the Throne. Agnes Davidson told me, the last time I saw her, that she was for the Union—and that she would no longer be a secessionist from the government of God, and would testify her love to Jesus and the Church at our next communion. Mary Davidson, a younger sister, left her home that morning, singing a beautiful hymn. Both were dutiful at home; both were loved at the Sabbath School, and both would probably have soon been fellow communicants. We hope all three are now with the blessed.

There are other things which are not so painful to look upon. This dark cloud has a silver lining.

Heroic courage was displayed. Men dashed into the midst of the burning to save, as dauntless as ever soldiers stormed a battery. The walls were scaled, burning fragments scattered, shrieking victims carried out, with bravery never surpassed, showing that peace and mercy have their heroes, without drum and fife, without the word of command or the presence of an insulting foe. One poor girl, who barely escaped with life, could hardly be prevented from rushing back to find her companion, and when hindered, wended her way slowly home, wailing, even upon a bed of pain, that her friend was lost.

The firemen of the cities were out with their engines, with a promptness truly praiseworthy. Fearing not the proximity of the magazine, regardless of the repeated explosions of the shells and cartridges, they poured their streams upon the burning mass as steadily as on a parade, or a common conflagration.

Physicians were there, unfed, uncalled, with the appliances of skill, to save or alleviate suffering. Clergymen were there, amidst smoke and fire, to point the dying to the Lamb of God.

Women were there, with lint and bandage, with oil and wine, with ready hands to soothe and words to encourage.

All classes were there, to sympathize, to do anything, mastering their own feelings as they attempted to console the sufferers. O! it was grand to see the heart of this community stirred to its inmost depths. The cloud had a silver lining; the sable pall was fringed with gold. Upon the deep back ground of this woe was painted a picture of heroism and love upon which angels might gaze with admiration….

How could those dear girls know that by the grinding of a wheel or the dropping of a shell, such dire calamity would be instantly brought upon themselves. The opening of a bale of strange merchandise let out the ‘great plague’ of London: the careless management of a little fire in a small yard started the ‘great fire’ of Pittsburgh. We are so linked together; our lives or deaths depend so much upon others, over whom we have no control, that we should be always ready. A carelessly prepared prescription, a drunken captain or conductor, may work harm. Who could foretell what the firing of the first gun at Fort Sumter would bring about? It brought about remotely, the catastrophe of Wednesday. And who can tell what more it may bring?

In conversing with so many dying persons in so short a space of time, their final words would naturally leave a deep impression. One as soon as rescued, exclaimed, ‘Tell me truly, will I die?’ You will. ‘Then cover me and take me out of the crowd.’ Several cried frantically, ‘Send for a priest.’ One declared that her only hope was in the Mother of God. Another said, ‘I die, but Jesus died for me; I am safe.’ One from a distant town cried almost unceasingly, ‘God have mercy on my poor wicked soul.’ One murmured indistinctly, what sounded like ‘Glory! glory!’ ‘My poor mother!’ ‘My poor children!’ were exclamations upon the lips of many. One ‘had done no harm, and hoped that her suffering would atone for her sins.’ A mother said, ‘I have worked for a living for my children, but, sir, if I live I will set them a better example. I will take them to your church. I have them baptized, but I should have done my duty better. God spare me to my children.’ These remarks show the feelings of persons of different creeds. When near to eternity, we must in deep agony lean upon something, either upon the Almighty God, through Jesus Christ our Lord, or upon a poor reed. One poor girl who escaped with fearful injury, seemed to forget herself entirely, and exclaimed continually to herself, or others, ‘My poor companion! she perished in the flames: I tried to save her, but could not,’ In the very midst of the awful scene, an intelligent physician said, ‘I heard glorious news just as I left the city, but can hardly tell it here; McClellan has defeated the rebels in Maryland, and will, without doubt, kill or capture them all.’ Patriotism for a moment lit the countenances of the bystanders with joy; but the smile was like a sudden gleam of sunshine across ruins. There was the terror from which such tidings as this could not divert the mind. Another physician exclaimed, ‘I was all along the Chickahominy during the battles, but was not affected as I am here—so unexpected—so terrible—and the sufferers, poor girls—the impossibility of even relieving them,’ pointing to some dozen blackened, quivering remains. Those who saw the sight can never forget it….

Iron City Arsenal

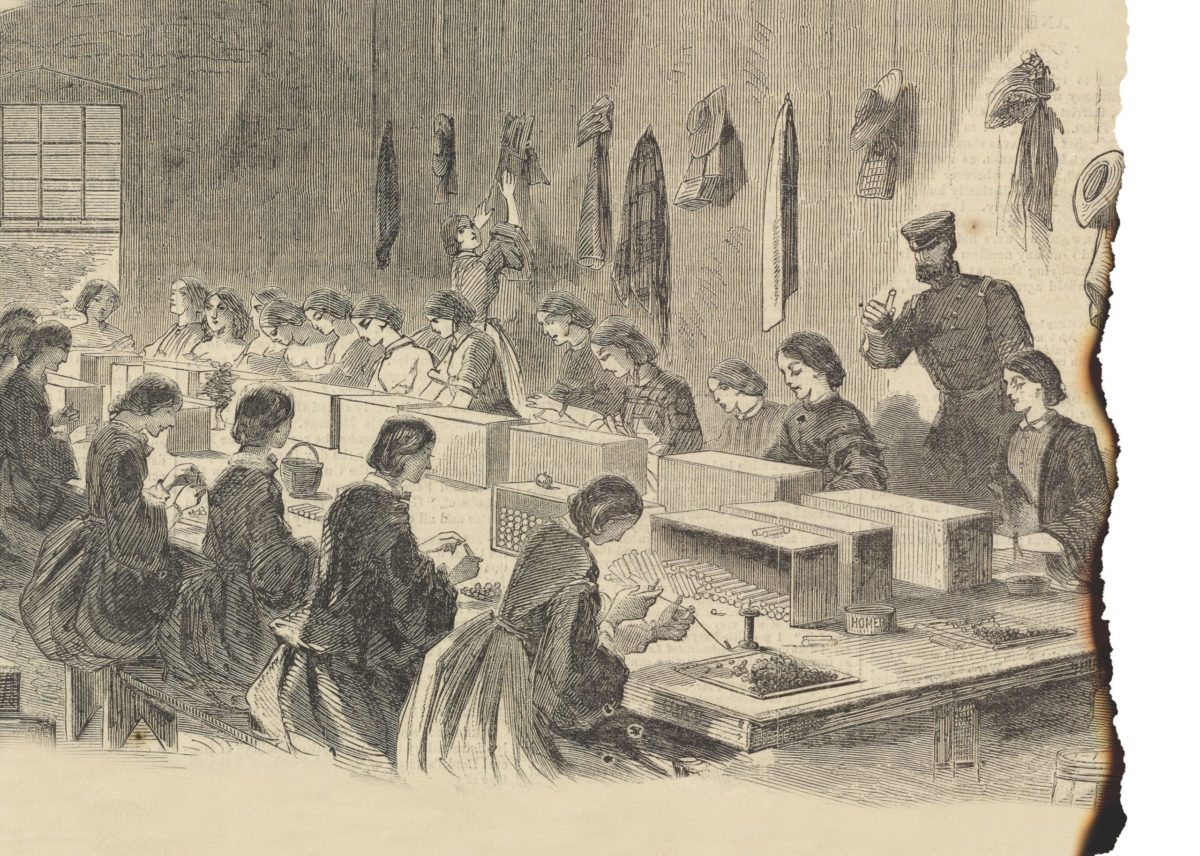

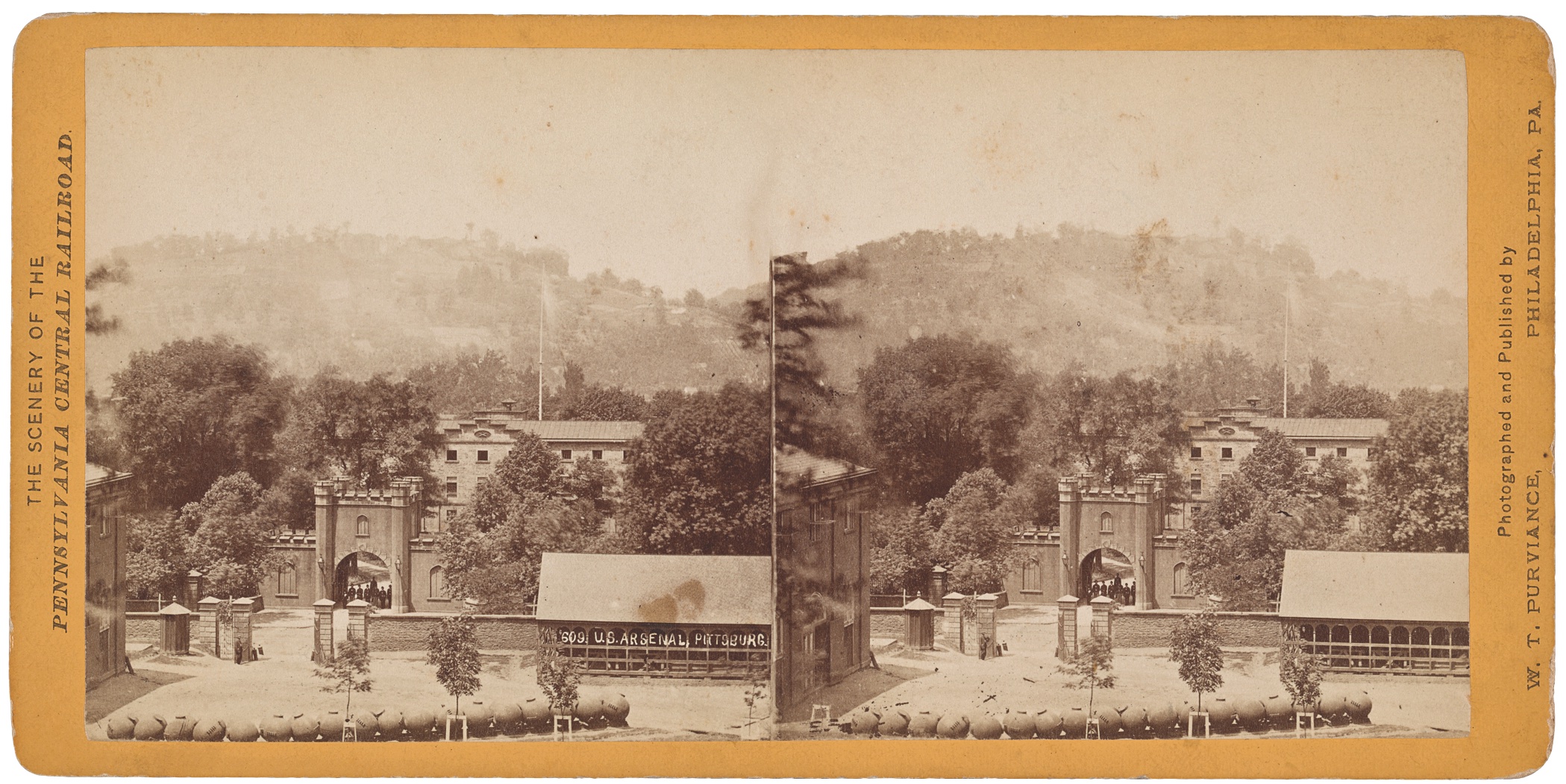

Situated just outside the Pittsburgh city limits in the borough of Lawrenceville, the Allegheny Arsenal was established in 1814 on 30 acres of land sold to the U.S. Ordnance Department by the borough’s founder, William B. Foster. The arsenal grounds were bordered by 39th and 40th Streets, Penn Avenue, and the Allegheny River—the latter which connected to the broader Ohio River and served as a major highway in transporting munitions, weapons, and supplies westward. By 1860 the arsenal encompassed 38 acres and employed a little more than 300 laborers; however, with war on the horizon, a larger workforce was required.

At the height of the Civil War, approximately 1,200 men and women reported for duty at the arsenal. As reported by the site’s colonel of ordnance, John Symington, to the Ordnance Department on October 2, 1861, nearly 200 male employees had been fired after “matches were discovered among the bundles of cartridges prepared to be packed, in one of the rooms… I have discharged all the boys at work in that portion of the laboratory, and will supply their places with females…” From that point on, a majority of those employed at the laboratory were women drawn from the surrounding community. With an efficient workforce in place, the laboratory’s daily output of small arms ammunition reached approximately 30,000 rounds, in addition to field artillery ordnance and various equipment for the Union Army. Even after the devastating explosion on September 17, 1862, manufacturing continued through the end of the war and toward the end of the 19th century. But with the decreased demand for military supplies after the war, the arsenal decreased production and, as stated by the Pittsburgh Daily Post in 1897, was “counted as one of the best storage places in the country for munitions of war.” The arsenal grounds decayed with the onset of the 20th century, and by 1926 had been sold off to make way for urban development as well as a city space for public use—the appropriately named Arsenal Park. Few buildings from the Allegheny Arsenal still remain, although reminders of the site’s past are visible in sections of the park’s bordering wall, as well as Powder Magazine No. 2, which, although now a public restroom, is the only building present from the arsenal’s 1814 construction. —R.C.

Ever since the fatal day, persons have visited the Arsenal, either to inquire about the whole occurrence, or in the faint hope of learning something of their lost ones. Sometimes deeply affecting scenes are witnessed….

As soon as the community recovered somewhat from the stunning blow, arose the questions, How did it happen? Is any one to blame? Might it have been prevented? The efforts to answer these questions were unparalleled in the history of this region. Public meetings and private investigations—discussions by the press—a coroner’s jury, with amazing perseverance and research—all combined, calling for light. From the fact that no one shrank from investigation, we most certainly believe that no one willfully committed the deed. But the road before the building was stony. Powder was hauled in great quantities in wagons. Even powder barrels may be leaky. The shop was swept out—sometimes loose powder among the dust. Familiarity breeds contempt of danger. All these are facts. So it is also true, that visitors have been long excluded from the shops—that the laboratory was guarded by stringent rules. Respecting the living—agents and employees—we say not one word, except that from the highest to the lowest, we believe every one of them utterly incapable of doing the deed purposely. The rigid examination will discover what amount of carelessness, or want of forethought, there existed, and determine the innocence or culpability of those in charge….”

Among those who gathered in Allegheny Cemetery on Memorial Day 1889 was former Arsenal employee Laura Guinn, who lost her sister in the explosion and barely escaped with her own life. In an 1890 interview with the Pittsburgh Press, championing pension rights for survivors and family members, Guinn emphasized, “I can show as many scars from injuries received as any soldier who lived through the war.” Much like the Rev. Lea, Guinn kept the memory of the departed alive through efforts of memorialization and recollection—an endeavor that was carried on into the the 20th century. Following his death in 1900, the Rev. Richard Lea’s remains were laid to rest within a short distance of the arsenal memorial. At the age of 90, he was the oldest and longest-serving Presbyterian minister in the state of Pennsylvania.

Western Pennsylvania native Rich Condon founded and maintains the Civil War Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania in the Civil War blogs, and he works as an NPS ranger at Reconstruction Era National Historical Park.