Ninety years ago a soon-to-be-famous author wrote of his own experiences in World War I.

James M. Cain’s life took a fateful turn one day in 1914 as he sat on a bench in Lafayette Park, across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House, contemplating his future. Some time earlier he had given up on his dream of becoming an opera singer. And now he had quit his job in the music department of Kann’s Department Store after being refused a raise. Suddenly he heard a voice—his own voice—say, “You’re going to be a writer.”

In time Cain would be one of America’s most famous writers—the author of such sensational and controversial novels as The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity, and Mildred Pierce. Starting out, though, he settled for a job as a cub reporter for the Baltimore American. But his fledging career as a newspaperman was interrupted when the United States entered World War I. Drafted into the army, Cain was soon shipped to France as a private in the headquarters troop of the 79th Division, an infantry unit raised at Camp Meade in his home state

of Maryland in 1917.

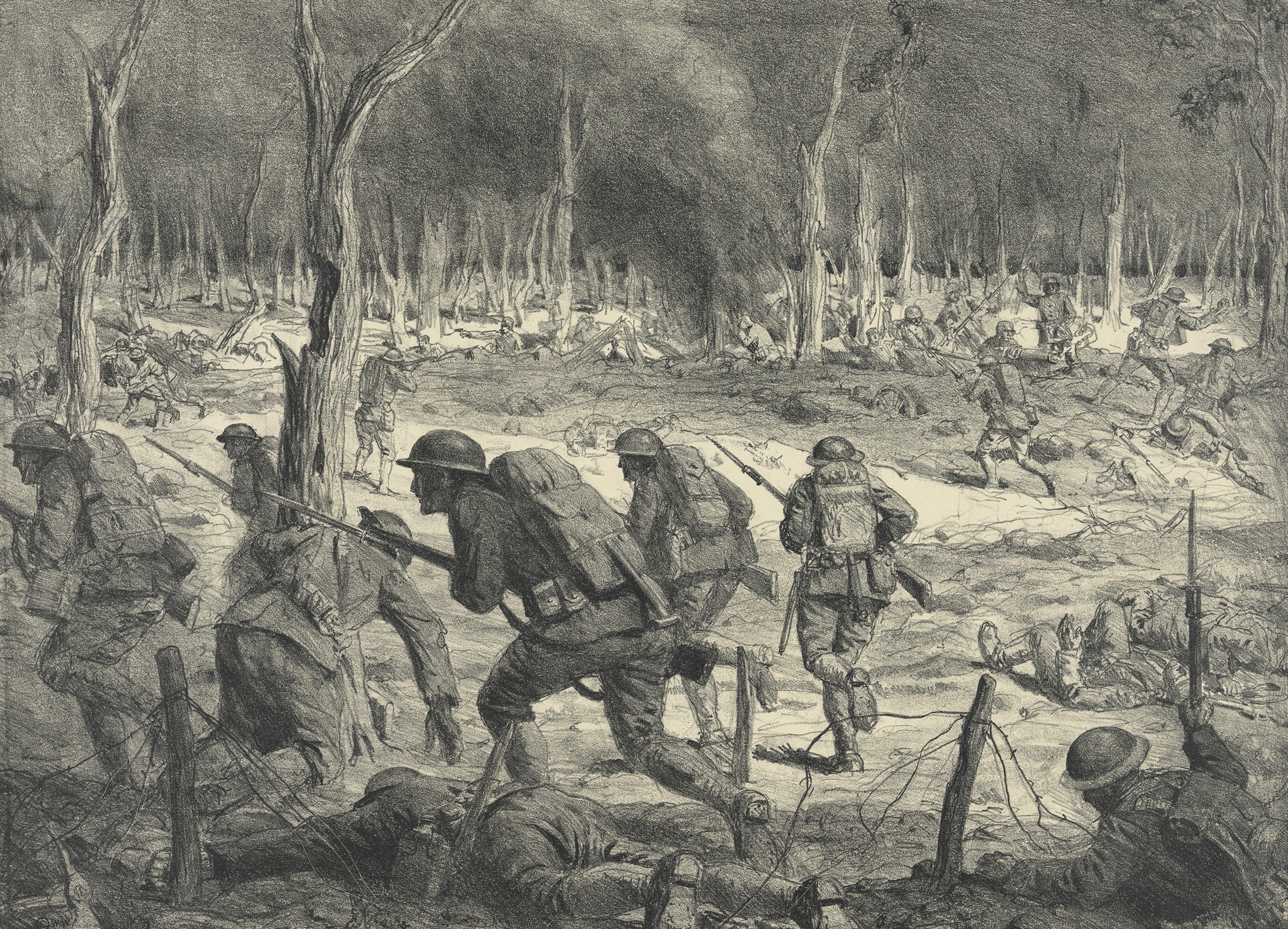

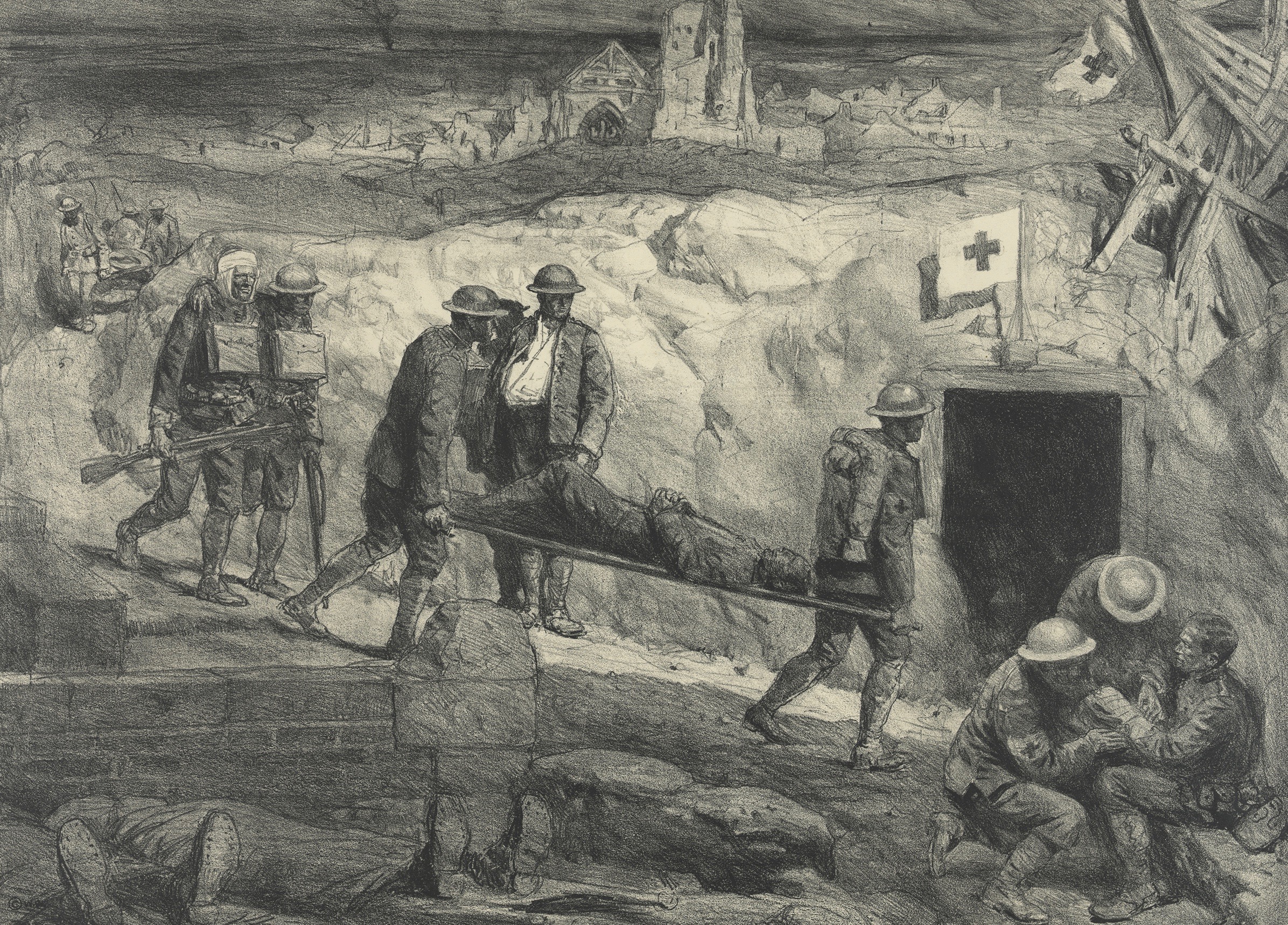

In the opening days of General John J. Pershing’s Meuse-Argonne Offensive—a massive attack that would, it was hoped, bring an end to World War I—the 79th Division was assigned the job of capturing Montfaucon, a German stronghold and commanding observation point that towered some 300 feet above the countryside. Cain served as a runner during the battle (one of the bloodiest sieges of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive) and after the armistice he became the editor in chief of the Lorraine Cross, the 79th Division’s “trench newspaper.”

Returning to the States, Cain spent three years working as a reporter for the Baltimore Sun. Then he began writing short stories for the American Mercury, the celebrated magazine that H. L. Mencken, the Sun’s influential and fearless iconoclast, had founded in 1924. The second of Cain’s stories for the American Mercury, “The Taking of Montfaucon,” was published in its June 1929 issue. The story was presented as fiction, but it was really an autobiographical tale based on Cain’s most harrowing wartime experiences. Cain tells the story not in his own voice but in the colloquial voice of a rube from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where he had spent many of his growing-up years.

In 1940, when Cain had achieved fame as a writer, the Infantry Journal reprinted “The Taking of Montfaucon,” saying that “it has never been excelled as an accurate description of conditions in the war and few stories of any aspect of the war will stand beside it.” The version of his story that follows appears exactly as it did in the American Mercury in 1929 and is reprinted with the permission of Harold Ober Associates (copyright 1929 by the James M. Cain Estate).

When Cain died in 1977 at age 85, his New York Times obituary noted that he always scoffed at how critics labeled him, saying that he didn’t think of himself as one of “the boys in the back room” or a “tough-guy writer of the ’30s.” (“I belong to no school, hard-boiled or otherwise,” Cain once wrote, “and I believe these so-called schools exist mainly in the imagination of critics.”) The Times obituary went on to point out that while Hollywood likely made more than $12 million on motion pictures based on Cain’s books, his own take was just a little more than $100,000.

I

I been ask did I get a D. S. C. in the late war, and the answer is no, but I might of got one if I had not run into some tough luck. And how that was is pretty mixed up, so I guess I better start at the beginning, so you can get it all straight and I will not have to do no back tracking.

On the 26th of September, 1918, when the old 79th Division hopped off with the rest of the A. E. F. on the big drive that started that morning, the big job ahead of us was to take a town name of Montfaucon, and it was the same town where the Crown Prince of Germany had his P. C. in 1916, when them Dutch was hammering on Verdun and he was watching his boys fight by looking up at them through a periscope. And our doughboys was in two brigades, the 157th and the 158th, with two regiments in each, and the 157th Brigade was in front. But they ain’t took the town. Because it was up on a high hill, and on the side of the hill was a whole lot of pillboxes and barbed wire what made it a tough job. Only I ain’t seen none of that, because I spent the whole day on the water wagon, along with another guy name of Armbruster, and we was driving it up from the Division P. C. what we left to the Division P. C. where we was going. And that there weren’t so good, because neither him, me, nor the horse hadn’t had no sleep, account of the barrage shooting off all night, and every time we come to one of them sixteen-inch guns going through the woods and a Frog would squat down and pull the cord, why the horse would pretty near die and so would we. But sometime we seen a little of what was going on, like when a Dutch aviator come over and shot down four of our balloons and then flew over the road where we was and everybody tooken a shot at him, only I didn’t because I happen to look at my gun after I pulled the bolt and it was all caked up with mud and I kind of change my mind about taking a shot.

So after awhile we come to a place in a trench and they said it was the new Division P. C., and Ryan, who was the stable sergeant, come along and took the horse, and we got something to eat and there was still plenty shelling going on, but not bad like it was, and we figured we could get some sleep. So then it was about six o’clock in the evening. But pretty soon Captain Madeira,4 he come to me and says I was to go on duty. And what I was to do was to go with another guy, name of Shepler to find the P. C. of the 157th Brigade, what was supposed to be 1,000 yards west of where we was, and then report back. And why we was to do that was so we could find the Brigade P. C. in the night and carry messages to it. Because us in the Headquarters Troop, what we done in the fighting was act as couriers and all like of that, and what we done in between the fighting was curry horse belly. So me and Shepler started out. And as the Brigade P. C. was supposed to be 1,000 yards west, and where we was in a trench, and the trench run east and west, it looked like all we had to do was follow the trench right into where the sun was setting and it wouldn’t be no hard job to find what we was looking for.

And it weren’t. In about ten minutes we come to the Brigade P. C., and there was General Nicholson, and his aides, and a bunch of guys what was in Brigade Headquarters, all setting around in the trench. But they was moving. They was all set to go forwards somewheres, and had their packs with them.

“Well,” says Shep, “we ain’t got nothing to do with that. Let’s go back.”

“Right,” I says. But then I got to thinking. “What the hell good is it,” I says, “for us to go back and tell them we found this P. C., when in a couple of minutes there ain’t going to be nobody in it?”

“What the hell good is the war?” says Shep. “We was told to find this P. C. and we’ve found it. Now we go back and let them figure out what the hell good it is.”

“This P. C.,” I says, “soon as the General clears out, is same as a last year’s bird’s nest.”

“That’s jake with me,” says Shep. “In this man’s army you do what you’re told to do, and we’ve done it. We ain’t got nothing to do with what kind of a bird’s nest it is.”

“No,” I says, “we ain’t done it. We was told to find a P. C. And soon as Nick gets out this ain’t going to be no P. C., but only a dugout. We got to go with him. We got to find where his new P. C. is at, and then we go back.”

“Well, if we ain’t done it,” says Shep, “that’s different.”

So in a couple of minutes Nick started off, and we went with him, and a hell of a fine thing we done for ourself that we ain’t went back in the first place, like Shep wanted to do. Because where we went, it weren’t over no road and it weren’t through no trench. It was straight up toward the front line over No Man’s Land, and a worse walk after supper nobody ever took this side of Hell. How we went was single file, first Nick, and then them aides, and then them headquarters guys, and then us. About every fifty yards, a runner would pick us up, and point the way, and then fall back and let us pass. And what we was walking over was all shell-holes and barbed wire, and you was always slipping down and busting your shin, and then all them dead horses and things was laying around, and you didn’t ever see one till you had your foot in it, and then it made you sick. And dead men. The first one we seen was in a trench, kind of laying up against the side, what was on a slant. And he was sighting down his gun just like he was getting ready to pull the trigger, and when you come to him you opened your mouth to beg his pardon for bothering him. And then you didn’t.

Well, we went along that way for a hell of a while. And pretty soon it seemed like we wasn’t nowheres at all, but was slugging along through some kind of black dream what didn’t have no beginning and didn’t have no end, and them goddam runners look like ghosts what was standing there to point, only we wasn’t never going to get where they was pointing nor nowheres else.

But after a while we come to a road and on the side of the road was a piece of corrugated iron. And Nick, soon as he come to that, unslung his musette bag and sat down on it. And then all them other guys sat down too. So me and Shep, we figured on that awhile, because at first we thought they was just taking a rest, but then Shep let on it looked like to him they was expecting to stay awhile. So then we went up to Nick.

“Sir,” I says, “is this the new Brigade P. C.?”

“Who are you?” he says.

“We’re from Division Headquarters,” I says. “We was ordered to find the Brigade P. C. and report back.”

“This is the new P. C.,” he says.

“This piece of iron?” I says.

“Yes,” says he.

“Thank you sir,” I says, and me and Shep saluted and left him.

“A hell of a looking P. C.,” says Shep, soon as we got where he couldn’t hear us.

“A hell of looking P. C. all right,” I says, “but it’s pretty-looking alongside of that trip we got going back.”

“I been thinking about that,” he says.

So we sat down by the road a couple of minutes.

“Listen,” he says, “I ain’t saying I like that trip none. But what I’m thinking about is suppose we get lost. I don’t mind telling you I can’t find my way back over them shell-holes.”

“I got a idea,” I says.

“Shoot,” he says.

“This here road we’re setting on,” I says, “must go somewheres.”

“They generally do,” he says.

“If we can find someplace what’s on one end of it,” I says, “I can take you back if you don’t mind a little walking. Because I know all these roads around here like a book.” And how that was, was because I had been on observation post before the drive started, and had to study them maps, and even if I hadn’t never been on the roads I knowed how they run.

“I’ll walk with you to sun-up,” he says, “if it’s on a road and we know where we’re going. But I ain’t going to try to get back over that No Man’s Land, boy, I’ll tell you that. Because I just as well try to fly.”

So we asked a whole lot of guys did they know where the road run, and not none of them knowed nothing about it. But pretty soon we found a guy in the engineers, what was fixing the road, and he said he thought the road run back to Avocourt.

“Lets go,” I says to Shep. “I know where we’re at now.”

So we started out, and sure enough after a while we come to Avocourt. And I knowed there was a road run east from Avocourt over the ridge to Esnes, if we could only figure out which the hell way was east. So the moon was coming up about then, and we remembered the moon come up in the east, and we headed for it, and hit the road. And a bunch of rats come outen a trench and begun going up the road in front of us, hopping along in a pretty good line, and Shep said they was trench camels, and that give us a laugh, and we felt better. And pretty soon, sure enough, we come to Esnes, and turned left, and in a couple minutes we was right back in the Division P. C. what we had left after supper, and it weren’t much to look at, but it sure did feel like home.

II

Well, we weren’t no sooner there than a bunch of guys begun to holler out to Captain Madeira that here we was, and he come a-running, and if we had of been a letter from home he couldn’t of been more excited about us.

“Thank God you’ve come,” he says.

“Sure we’ve come,” says Shep; “you wasn’t really worried about us, was you?”

But I seen it was more than us the Captain was worrying about, so I says:

“What’s the matter?”

“General Nicholson has broken liaison,” he says, “and we’ve got not a way on earth to reach him unless you fellows can do it.”

“Well, I guess we can, hey kid?” I says to Shep.

But Shep shook his head. “Maybe you can,” he says, “but I ain’t got no more idea where we been than a blind man. I’ll keep you company, though, if you want.”

“Company hell,” says the Captain.” “Here,” he says to me, “you come in and see the General.”

So he brung me into the dugout what was the P. C. to see General Kuhn.7 And most of the time, the General was a pretty snappy looking soldier. He was about medium size, and he had a cut to his jaw and a swing to his back what look like them pictures you see in books. But he weren’t no snappy looking soldier that night. He hadn’t had no shave, and his eyes was all sunk in, and no wonder. Because when the Division ain’t took Montfaucon that day, like they was supposed to, it balled everything up like hell. It put a pocket in the American advance, a kind of a dent, what was holding up the works all along the line. And the General was getting hell from Corps, and he had lost a lot of men, and that was why he was looking like he was.

“Do you know where General Nicholson is?” he says to me, soon as Captain Madeira had told him who I was.

“Yes sir,” I says, “but I don’t think he does.”

Now what the General said to that I ain’t sure, but he mumbled something to hisself what sounded like he be damned if he did either.

“I want you to take a message to him,” he says.

“Yes sir,” I says.

So he commenced to write the message. And while I was standing there I was so sleepy everything look like it was turning around, like them things you see in a dream. It was a couple of aides in there, and maybe a orderly, and Captain Madeira, and it was in behind a lot of blankets, what they wet and hang over the door of a dugout to keep out gas. And in the middle of it was General Kuhn, writing on a pad in lead pencil, and I remember thinking how old he looked setting there, and then that would blank out and I couldn’t see nothing but his whiskers, and then that would blank out and I would be thinking it was pretty tough on him, and I would do my best to help him out. It weren’t no more than a minute, mind. Why I was thinking all them things jumbled up together was because I hadn’t had no sleep.

“All right,” he says to me; “listen now while I read it to you.”

And why they read it to you is so if you lose it you can tell them what was in it and you ain’t no worse off. And he hadn’t no sooner started to read it then I snapped out of that dream pretty quick. Because it was short and sweet. It said that Nick was to attack right away soon as he got it. And I knowed a little about this Montfaucon stuff from hearing them Brigade guys talk while we was going over No Man’s Land, so I knowed I weren’t carrying no message what just said good morning.

“Is that clear to you?” he says.

“Yes sir,” I says.

“Deliver that to General Nicholson,” he says.

“Yes sir,” I says.

“Captain, give this man a horse. As good a horse as you’ve got.”

“Yes sir,” says the Captain.

“You better ride pretty lively. And report back to me here.”

“Yes sir.”

“No, wait a minute, I’m moving my P. C. to Malancourt in the next hour. Do you know where Malancourt is?”

“Yes sir.”

“Hunh,” he says, like he meant thank God there was somebody in the outfit what knowed right from left, and I was glad I had studied them maps good like I had and could be some use to him.

“Then report to me in Malancourt.” And me and the Captain saluted and went out.

So the Captain took me to Ryan, and Ryan saddled me a horse, and while he was doing it Shep come up and begun to talk about the argument we had about whether we was going with Nick or not, and he handed it to me for figuring out the right thing to do, and the Captain said he was goddam proud of us both for carrying out orders with some sense when everybody else act like they had went off their nut and things was all shot to hell, and I felt pretty good. So pretty soon Ryan come with the horse, and I started out, and after I had went about a couple miles it was commencing to get light, so I dug my heels in, because I knowed I didn’t have much time.

III

Well, in another five minutes I come to Avocourt. And soon as I rode around the bend I got a funny feeling in my stomach. Because I seen something I had forgot when me and Shep was there, and that was that there was two roads what run from Avocourt up to the front line, one of them running north and the other running northeast, and they kind of forked off from each other in a such a way that when you was coming down one of them like we done you wouldn’t notice the other one at all. And I knowed as soon as I looked at them that I didn’t have no idea which one we had come over and it weren’t no way to find out.

So I pulled in and figured. And I closed my eyes and tried to remember how that road had looked when we was coming back down it into Avocourt, with the moon rising on our left before we hit the road to Esnes, and that was dam hard, because I was so blotto from not having no sleep that soon as I closed my eyes all I got was a bellering in my ears. But I squinched them up good, and pretty soon it jumped in front of me, how that road looked, and right near Avocourt was a bunch of holes in the middle of it, what look like a tank had got stuck there and dug them up trying to get out. So I opened my eyes and was all set to hit for them holes. But I knowed I was in for it good. Because in between while we had been over the road, them engineers had surfaced it, and it weren’t no holes, because they was all covered with stone.

But it weren’t doing no good setting on top of the horse figuring, so I picked the righthand road and started up it. I figured I would go about as far as me and Shep had come, and then maybe I would run into Nick, or somebody that could tell me where he was at, or what the right road was to take, and that the main thing was to get a move on. But that there sounds easier than it was. Because once you start out somewheres, and get to wondering are you headed right or not, you’re bad off, and you might just as well be standing still for all you’re going to get there.

I kept pushing the horse on, and every step he took I would look around to see if I could see something that me and Shep had seen, and about all I seen was tanks and engineers forking stone, what was what we had saw the night before, but it didn’t prove nothing because you could see tanks and engineers on any road. And them engineers wasn’t no help, because engineers is dumb as hell and then they ain’t got nothing to do with fighting outfits and 157th Brigade sounds just the same to them as any other Brigade, and a hell of a wonder me and Shep had found one the night before that could even tell us which way the road run.

Well, after I had went a ways, about as far as I thought me and Shep had come, and ain’t seen a thing that I could say for certain we had saw the night before, and no sign of Nick or his piece of corrugated iron, what might be covered up with stone too for all I knowed, I figured I was on the wrong road sure as hell, and I got a awful feeling that I would have to go back to Avocourt and start over again. Because that order in my pocket, it weren’t getting no cooler, I’m here to tell you. It was dam near burning a hole in my leg, and a funny hiccuppy noise would come up out of my neck every time I thought of it.

But I went on a little bit further, just to make sure, and then I come to something that I thought straightened me all out. It was a kind of a crossroads, bearing off to the left. And I couldn’t remember that we had passed it the night before, so I figured I must of gone wrong when I tooken the righthand fork at Avocourt. But this road, I thought, will put me right, because it leads right acrost to the other one and I won’t have to lose all that time going back to Avocourt. So I helloed down it, and for the first time since I left Avocourt I felt I was going right. And sure enough, pretty soon I come to the other road, and it weren’t no new stone on it at that place, so I turned right, towards the front, and started up it. And I worked on the horse a little bit, because without no loose stone under his foot he could go better, and kind of patted him on the neck and talked to him, because he hadn’t had no sleep neither and he was tired as hell by this time, and then I lifted him along so he went in a good run. And it weren’t quite light yet, and I thought thank God I’ll be in time.

IV

So pretty soon I come to some soldiers what wasn’t engineers. So I pulled up and hollered out:

“What way to the 157th Brigade P. C.?”

“The what?” they says.

“The 157th Brigade P. C.,” I says. “General Nicholson’s P. C.”

“Never hear tell of it,” they says.

“The hell you say,” I says. “And you’re a hell of a goddam comical outfit, ain’t you?”

Because that was one of them gags they had in the army. They would ask a guy what his outfit was, and then when he told them they would say they never hear tell of it.

So I rode a little further and come to another bunch. “Which way is the 157th Brigade P. C.?” I says. “General Nicholson’s P. C.?”

But they never said nothing at all. Because they was doughboys going up in the lines, and when you hear somebody talk about doughboys singing when they’re going up to fight, you can tell him he’s a dam liar and say I said so. Doughboys when they’re going up in the lines they look straight in front of them and they swaller every third step and they don’t say nothing.

So pretty soon I come to another bunch what wasn’t doughboys and I asked them. “Search me, buddy,” they says, and I went on. And I done that a couple more times, and I ain’t found out nothing. So then I figured it weren’t no use asking for the Brigade P. C. no more, because a lot of them guys they wouldn’t never of hear tell of the 157th Brigade even if they was in it, so I figured I would find out what outfit they was in and then I could figure out from that about where I was at. So that’s what I done.

“What outfit, buddy?” I says to the next bunch I come to. But all they done was look dumb, so I didn’t waste no more time on them, but went on till I come to another bunch, and I asked them.

“A. E. F.,” a guy sings out.

“What the hell,” I says. “You think I’m asking just for fun?”

“Y. M. C. A.,” says another, and I went on. And then all of a sudden I knowed why them guys was acting like that, and why it was was this: Ever since they come to France, they had been told if somebody up in the front lines asks you what your outfit is, don’t you tell him because maybe he’s a German spy trying to find out something. Because of course they wasn’t really worried none that I was a German spy. What they was worried about was that maybe I was a M.P. or something what was going around finding out how they was minding the rule, and they wasn’t taking no chances. Later on, when a whole hell of a lot of couriers had got lost and the American Army didn’t know was it coming or going, they changed that rule. They marked all the P. C.’s good so you could see them, and had arrows pointing to them a couple miles away so you couldn’t get lost. But the rule hadn’t been changed that morning, and that was why them guys wouldn’t say nothing.

Well, was you ever in a lunatic asylum? That was what it was like for me from that time on. I would ask and ask, and all I ever got was “Y. M. C. A.,” or “Company B,” or something like that, and it was getting later all the time, and me with that order in my pocket. And after a while I thought well I got to pretend to be a officer and scare somebody into telling me where I’m at. So the first ones I come to was a captain and a lieutenant setting by the side of the road, and they was wearing bars. But me not having no bars didn’t make no difference, because up at the front some officers wore bars but most of them didn’t, and if you take the bars off, one guy without a shave looks pretty much like another. So I went up to them and saluted and spoke sharp, like I had been bawling out orders all my life.

“Which way is General Nicholson’s P. C.?” I says, and the captain jumped up and saluted.

“General Nicholson?” he says. “Not around here, I’m pretty sure, sir,” he says.

“Hundred and Fifty-Seventh Brigade?” I says, pretty short, like he must be asleep or something if he didn’t know where that was.

“Oh no,” he says. “That wouldn’t be in this division. This is all 37th.”

So then I knowed I was sunk. The 37th Division, it was on our left, and that meant I had been on the right road all the time when I left Avocourt, as I seen many a time since by checking it up on the maps, and had went wrong by wondering about that fork. And it weren’t nothing to do but cut across again, and hope I might bump into General Nicholson somehow, and if I didn’t to keep on beating to Malancourt, so I could report to General Kuhn like I had been told to do. And what I done from then on I ain’t never figured out, even from them maps, because I was thinking about that order all the time, and how it ought to been delivered already if it was going to do any good, and I got a little wild. I put the horse over the ditch and went through the woods, and never went back to the crossroads at all. And them woods was full of shell-holes, so you couldn’t go straight, and the day was still cloudy, so you couldn’t tell by the sun which way you was headed, and it weren’t long before I didn’t know which the hell way I was going. One time I must of been right up with the fighting, because a guy got up out of a shell-hole and yelled at me for Christ sake not go over the top of that hill with the horse, because there was a sniper a little ways away, and I would get knocked off sure as hell. But by that time a sniper, if he only knowed where the hell he was sniping from, would of looked like a brother, so I went over. But it weren’t no sniper, because I didn’t get knocked off.

And another time, I come to the rim of a shell-hole what was so big you could of dropped a two-story house in it, and right new, but it weren’t no dirt around it and you couldn’t see no place the dirt had went. And right then the horse he wheeled and begun to cut back toward where we had come from. Because he was so tired by then he was stumbling every step and didn’t want to go on. So I had to fight him. And then I got off and begun to beat him. And then I begun to blubber. And then I begun to blubber some more on account of how I was treating the horse, because he ain’t done nothing and it was up to me to make him go.

And while I was standing there blubbering, near as I can figure out, the 313th, what was part of the 157th Brigade, was taking Montfaucon. Because General Kuhn he ain’t sat back and waited for me. Soon as I left him he got on a horse and rode up to the front line hisself, there in the dark, and passed the word over they was to advance, and then relieved a general what didn’t seem to be showing no signs of life, and put a colonel in command at that end of the line, and pretty soon things was moving. So Nick, he got the order that way and went on, and the boys, if they had Nick in command, they would take the town all right. So they took it.

V

It must have been after eleven o’clock when I got in to Malancourt. And there by the side of the road was General Kuhn, all smeared up with mud and looking like hell. And I went up to him and saluted.

“Did you deliver that message?” he says.

“No sir,” I says.

“What!” he says. “Then what are you doing coming in here at this hour?”

“I got lost,” I says.

He never said nothing. He just looked at me, starting in from my eyes and going clear down to my feet, and that there was the saddest look I ever seen one man turn on another. And it weren’t nothing to do but stand there, and hold on to the reins of the goddam horse, and wish to hell the sniper had got me.

But just then he looked away quick, because somebody was saluting in front of him and commencing to talk. And it was Nick. And what he was talking about was that Montfaucon had been took. But he didn’t no more than get started before General Kuhn started up hisself.

“What do you mean!” he says, “by breaking liaison with me? And where have you been anyway?”

“Where have I been?” says Nick. “I’ve been taking that position, that’s where I’ve been. And I did not break liaison with you!”

So come to find out, them runners what had showed us the way over No Man’s Land was supposed to keep liaison, only it was their first day of fighting, same as it was everybody else’s, and what they done was keep liaison with that last year’s bird’s nest what Nick had left, and didn’t get it straight they was supposed to space out a little bit till they reached to the Division P. C.

“And anyway,” says Nick, “there was a couple of your own runners that knew where I was. Why didn’t you use them?”

So of course that made me feel great.

So then they begun to cuss at each other, and the generals can outcuss the privates, I’ll say that for them. I kind of saluted and went off, and then Captain Madeira, he come to me.

“What’s the matter?” he says.

“Nothing much,” I says.

“You didn’t make it, hey?”

“No. Didn’t make it.”

“Don’t worry about it. You did the best you could.”

“Yeah, I done the best I could.”

“You’re not the only one. It’s been a hell of a night and a hell of a day.”

“Yeah, it sure has.”

“Well—don’t worry about it.”

“Thanks.”

So that is how I come not to get no D. S. C. in the late war. If I had of done what I was sent to do, maybe they would of give me one, because Shep, he got cited, and they sure needed me bad. But I never done it, and it ain’t no use blubbering over how things might be if only they was a little different. MHQ

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War Stories | The Taking of Montfaucon

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!