On September 6, 1774, at dawn, the town of Worcester, Mass., awoke to the sounds of fife and drum. Forty-five militiamen from Winchendon, near the New Hampshire border, marched in from the north. One hundred fifty-six from Uxbridge, by the Rhode Island border, came up from the south. The militia companies belonged to 37 different towns. According to a head count taken by one of the participants, they totaled 4,622, half the adult male population of sprawling, rural Worcester County. It was the largest assemblage of people ever to congregate in Worcester, and certainly the most historic. The militiamen’s mission: to close the quarterly session of the Court of General Sessions and the Court of Common Pleas, the official purveyors of British political and judicial authority in this distant outpost of the empire.

Why had it come to this?

As punishment for the Boston Tea Party the previous December, Parliament had passed the Coercive Acts, which closed the port of Boston, allowed the governor to move the trials of Crown officials accused of wrongdoing to Britain and strengthened the governor’s ability to house troops in colonial towns. But it was the Massachusetts Government Act, which unilaterally revoked key provisions of the provincial charter, that caused the biggest uproar.

For a century and a half, Massachusetts residents had governed themselves in most matters through their town meetings. Three out of four adult white males in the colony held the right to participate in town meetings and to vote; in rural areas like Worcester, 90 percent of the men were enfranchised. Now, in an instant, these men were silenced. No town meetings could be held without the express consent of the Crown-appointed governor, who also needed to approve all agenda items. Elected representatives of the towns had always helped choose the powerful Council, which served as both the upper house of the Massachusetts legislature and the governor’s executive arm, but henceforth the Crown would appoint all Council members as well as local sheriffs, justices of the peace and juries. A family could now have its property seized by officials who were accountable to the Crown, not the people.

Understandably, the people of Massachusetts rose as a body to say, “No way!” Earlier, people whom patriots labeled “Tories” had been able to muster reasonable (if unpopular) arguments in support of British policies such as taxation, but Tory pleas for accommodation lost all appeal in the face of mass disenfranchisement. Petitions would not suffice. The only viable way to thwart the Massachusetts Government Act was noncompliance: Government must be shut down, and that was the business of the day.

In Worcester on the morning of September 6, two dozen Tory officials, dressed primly in suits and wearing wigs, showed up to open the county courts. They found the courthouse occupied by patriots and the door firmly boarded. Forced to go elsewhere, they huddled inside Daniel Heywood’s tavern, halfway between the courthouse and the town meetinghouse on Main Street. There they waited for the militiamen to stipulate terms.

In Worcester on the morning of September 6, two dozen Tory officials, dressed primly in suits and wearing wigs, showed up to open the county courts. They found the courthouse occupied by patriots and the door firmly boarded. Forced to go elsewhere, they huddled inside Daniel Heywood’s tavern, halfway between the courthouse and the town meetinghouse on Main Street. There they waited for the militiamen to stipulate terms.

This took some time. The militiamen gathered first on the town green, but when that space proved too small, they moved to the open field behind Steven Salisbury’s store, kitty-corner to the courthouse. Each militia company had already elected a captain; now the companies chose representatives to deal with the court officials. In committee, the representatives were to prepare a formal surrender statement for the court officials, but the militiamen at large had to approve it first. The initial draft, according to an informant, was deemed merely “a paper…Signifying that they would Endeavor &c.” Finding this “not satisfying,” the militiamen instructed their representatives to formulate something stronger.

At 2 p.m., the officials were still inside the tavern, while the militiamen outside were growing restless. Finally, terms were reached: Because “unconstitutional” acts of Parliament had reduced the inhabitants of Massachusetts “to mere arbitrary power,” the officials would close the courts and refuse to exercise their offices.

This was satisfactory, but the militiamen also wanted the officials to repeat their renunciations in public. Accordingly, the companies lined up on either side of Main Street for more than a quarter mile, from Heywood’s Tavern to the courthouse. Then, one by one, each official was made to walk the gantlet, hat in hand, and recite his promise to refrain from enforcing Parliament’s dictates some 30 times over so all the militiamen could hear. With this humiliating display of submission, all British authority, both political and military, disappeared from Worcester County, never to return.

Until the Massachusetts Government Act, re-sistance to British measures had centered on Boston, where Samuel Adams and his comrades loudly decried the Crown’s usurpation of their rights for almost 10 years. Now the momentum had shifted away from Boston’s well-known patriots. Courts were closed in Worcester and all contiguous, mainland counties in Massachusetts except Suffolk, where the “shiretown” (county seat) of Boston was occupied by some 3,000 British troops who offered protection to Crown officials.

On August 30 in Springfield, shiretown for Hampshire County, more than 3,000 patriots marched “with staves and musick” to unseat court officials. “Amidst the crowd in a sandy, sultry place, exposed to the sun,” said one observer, judges were forced to renounce “in the most express terms any commission which should be given out to them under the new arrangement.”

On October 4 in Plymouth, several thousand militiamen gathered to dismantle the courts. Afterward, according to a contemporaneous report, the rebels were so excited that they “attempted to remove a Rock (the one on which their fore-fathers first landed, when they came to this country) which lay buried in a wharfe five feet deep, up into the center of the town, near the court house. The way being up hill, they found it impracticable, as after they had dug it up, they found it to weigh ten tons at least.” Excited patriots could dislodge British authority, but not Plymouth Rock.

In addition to closing the courts, citizens throughout the province continued to gather in town meetings, defying Parliament’s edict. General Thomas Gage, the Crown-appointed governor of Massachusetts and commander of the king’s forces in North America, found this out the hard way. He had just moved the capital of the province to Salem, hoping to distance himself from unrest in Boston, but local patriots called a town meeting only one block from his new headquarters. When Gage arrested seven men he accused of being ringleaders, 3,000 farmers marched on the jail to set the prisoners free. Two companies of British soldiers, on duty to protect the governor, retreated rather than force a bloody confrontation.

Meanwhile, Massachusetts patriots harassed the 36 Council members appointed by the Crown, forcing them either to refuse their commissions or retreat to the safety of British-garrisoned Boston. The once popular Timothy Ruggles, widely known as the “Brigadier” for his exploits in the French and Indian War, dared not go home to Hardwick in Worcester County after taking his oath of office, but patriots hounded him wherever he went. They painted the body of his prized horse and cut off its mane and tail. Threatened and hunted, the mighty Brigadier, now a refugee, fled to Boston.

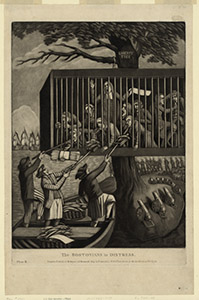

Abijah Willard, a “large and portly” Tory from Lancaster, after being sworn in as a Council member, traveled immediately to Connecti-cut, but he was recognized, thrown in jail for a night and ushered back to Massachusetts, where a crowd voted to send him to the Newgate prison unless he renounced his position. A man who voiced support for Willard “was stripped, and honored with the new fashion of dress of tar and feathers; a proof this, that the act of tarring and feathering is not repealed.” In his recantation, published in Boston newspapers, Willard “freely and solemnly” resigned from the Council and begged “forgiveness of all honest, worthy gentlemen that I have offended.” But Willard’s recantation, by any objective standard, was hardly offered “freely.”

By mid-October 1774 British rule had terminated in all of Massachusetts outside of Boston. General Gage reported to Lord Dartmouth, secretary of state for the colonies, that “the Flames of Sedition” had “spread universally throughout the Country beyond Conception.” One disgruntled Tory summed it all up in his diary: “Government has now devolved upon the people, and they seem to be for using it.”

Although the Massachusetts Revolution of 1774 was widespread, the court closure in Worcester was a pivotal moment. As early as July 4, upon learning that Parliament had disenfranchised the citizenry, Worcester’s radical caucus, the American Political Society, declared “that each, and every, member of our Society, be forth with provided, with two pounds of gun powder each 12 flints and led answerable thereunto.” For the next two months the people of Worcester prepared to make their stand.

Although the Massachusetts Revolution of 1774 was widespread, the court closure in Worcester was a pivotal moment. As early as July 4, upon learning that Parliament had disenfranchised the citizenry, Worcester’s radical caucus, the American Political Society, declared “that each, and every, member of our Society, be forth with provided, with two pounds of gun powder each 12 flints and led answerable thereunto.” For the next two months the people of Worcester prepared to make their stand.

On August 27, only 10 days before the courts were supposed to convene, Gage had written to Lord Dartmouth: “In Worcester, they keep no Terms, openly threaten Resistance by Arms, preparing them, casting Ball, and providing Powder, and threaten to attack any Troops who dare to oppose them.” He then vowed to “march a Body of Troops into that Township” to keep the courts open.

Gage had not intervened when the people of Great Barrington suddenly closed the Berkshire County courts on August 16, but that was 140 miles away at the far western reach of the province, and he had received little notice. Worcester, on the other hand, was only 40 miles away, and Gage had plenty of time to prepare. The commander for British North Ameri-ca needed to hold the line somewhere, and he drew that line at Worcester. But members of Gage’s Council, who had been driven from their homes by angry patriots, advised him otherwise. “Disturbance being so general, and not confined to any particular spot,” they told him, “there was no knowing where to send [the troops] to be of any use.”

On September 2 patriots gave Gage a preview of what he might expect if he dispatched troops to protect the courts. Responding to a rumor that six patriots had been shot by British troops and Boston had been set aflame, tens of thousands of New England militiamen (contemporaneous estimates ranged from 20,000 to 100,000) gathered on their respective town greens and marched under arms toward Boston to set matters right. Upon learning that the rumor was false, the militiamen returned to their homes, but Gage had seen all he needed to see. If he sent a thousand or even 2,000 British regulars to Worcester, they would be overwhelmed by an armed populace.

On September 5, when intelligence arrived in Worcester that Gage would take no stand, the American Political Society resolved “not to bring our fire-arms into town the 6 day of Sept.”—the sheer force of numbers would suffice. Two dozen court officials were no match for thousands upon thousands of militiamen, with or without arms. Some militiamen who hadn’t heard the news brought their guns anyway, but most marched into town bearing only staves. There would be no loss of life or limb—this revolution was so powerful that nobody had to bleed.

With British rule gone, what next? No one wanted to live under a tyrannical regime that refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of the people, but neither did they want to live in a “state of nature,” where anarchy reigned. On October 4, 1774, exactly 21 months before the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, the Worcester Town Meeting issued revolutionary instructions to Timothy Bigelow, its delegate to the upcoming Provincial Congress—an extralegal governing body elected by the people and outlawed by Gage, to no effect. Bigelow was to “exert” himself “in devising ways and means to raise from the dissolution of the old constitution, as from the ashes of the Phenix [sic], a new form, wherein all officers shall be dependent on the suffrages of the people,” and to do this despite any “unfavorable constructions our enemies may put upon such procedure.” It was the first known declaration in favor of an independent government by a public body in British North America.

The idea of “independency,” as it was called at the time, frightened the famous Boston radicals. Samuel and John Adams, attending the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, informed friends back home that “independency” and “setting up a new form of government” would only alienate potential allies in other colonies. Such notions “startle people here,” John Adams wrote, while Samuel Adams urged Boston’s leaders to slow down the revolution in the countryside. But Bostonians were no longer in the vanguard. Country people were. They were the ones to force the issue, while their celebrated compatriots tried to rein them in.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1774-75, Massachusetts revolutionaries organized. Minutemen trained. Towns paid their taxes not to the official tax collector but to the upstart Provincial Congress, which used the funds to procure weapons and powder. Intelligence networks were formed. If and when the British made their move, the patriots would be ready.

General Gage, meanwhile, could do little but watch and wait. “Old woman,” people started calling him, but really he had no choice. Not until London sent him more troops would he dare venture into the patriot-controlled countryside. But the Crown would send more troops. It had to. If it let Massachusetts slip from its grasp, other colonies would certainly follow.

Knowing reinforcements would likely arrive in the spring, Gage prepared for an offensive. He dispatched spies to survey the patriots’ strength. Could he possibly strike at Worcester, the very heart of resistance? According to the spies’ report, patriots had accumulated 15 tons of powder (hidden in unknown places), 13 small cannons (proudly displayed but poorly mounted in front of the meetinghouse on Main Street) and various munitions. But the road there was rough, the journey arduous and the patriots numerous, vigilant and excessively hostile. Gage’s soldiers would likely be vanquished.

In April 1775, when General Thomas Gage finally received his reinforcements, he decided instead to go after Lexington and Concord, closer and presumably easier targets than Worcester. The rest is history.

So why has this unprecedented transfer of authority been overlooked? The reasons lie in the grammar of popular historical narratives. The telling of history cries out for individual protagonists, but there was no one person, nor even a small group, that could have made the Revolution of 1774 more or less than it was. This revolution was conducted by and for thousands of largely anonymous participants, giving it both power and legitimacy. There was no entrenched leadership, no chain of command, no concrete definition. The whole episode has been as confusing, perhaps, to students of history as it was to General Gage, who had no idea how to respond.

At Lexington, professional British soldiers fired at a handful of local farmers. This act, allegedly perpetrated by the enemy, gave Americans the moral high ground and helped mobilize support. The story of that event, pitting Americans as David against the British Goliath, has been repeated so often it has effectively muffled the revolution of the preceding year, when the patriots of rural Massachusetts risked their all because they had lost the power of their vote. Leaderless, widespread and bloodless, the first transfer of political and military authority from the British to the Americans has not been able to compete with the familiar narrative. It was not lacking as a revolution; it has only lacked an audience to comprehend and appreciate it.

Ray Raphael is the author of The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (The New Press) and 16 other books. To view primary documents from the Revolution of 1774, visit www.rayraphael.com/documents.htm.

Watch author Ray Raphael talk about the Revolution of 1774.