Oh, damn it.” Somewhere near Charlottesville, Va., Greg Gordon is scanning the expanse before him—the landscape mostly flat, a few rocky hills and groves of trees posing formidable barriers. Behind those trees, he knows, the enemy is waiting. Gordon doesn’t like the hand fate has dealt him, so he has to move wisely. He positions soldiers on horseback in front of him. On his flanks, artillerymen are poised and ready. The weather is cold, gray, and drizzling, but it hardly matters. Within moments, the armies will advance.

On the other side from Gordon, Shane McBee is surveying his own options. “Don’t like that,” he says, examining available tactics. “Really don’t like that.” He pauses, considering. When he finally makes his move—a surprising one, a retreat—Gordon groans. It’s thrown off his plan for an assault. Now he’ll have to rethink everything. In the distance, other men murmur and grumble and occasionally cheer.

The backdrop for these contests is not a sprawling battlefield, but a DoubleTree Hotel about five miles from the University of Virginia campus, host to the annual Prezcon board gaming convention. Gordon and McBee are among dozens of players who have been playing in a tournament of the Civil War game Battle Cry, a popular tabletop game that hinges on both lucky die rolls and strategic maneuvers. The 2020 convention, held in late February before the pandemic closed down such things, drew hundreds of gamers for a week of tournaments. Hundreds of board games were in play, with several focused on the Civil War.

Even in this digital age, board gaming appears to be on the rise, with well-known titles such as Settlers of Catan, Ticket to Ride, and Clue flying off store shelves and filling online shopping carts. Board-based wargaming in particular, which became widely popular in the 1970s and ’80s, has also enjoyed a resurgence in recent years, according to game sellers and enthusiasts, with games such as Axis & Allies, Churchill, and 1775: Rebellion routinely topping rankings. Civil War games, including such titles as Lincoln, Fire and Fury, A House Divided, and Terrible Swift Sword among many others, have maintained a loyal fan base along with them.

As with many things related to the Civil War, the devotion is deep. At his table at Prezcon, Gordon makes a decision. “I’m just going to go for the gusto,” he says. “Assault on the right flank! Come on, boys!”

Casualties mount. The landscape shifts. The battle is on.

Board games of various forms have existed for thousands of years. An early version of chess dates to the 6th century in India, and other ancient games such as pachisi (popularized in the U.S. as Parcheesi and Sorry!) and backgammon are still played today as well. By the Civil War, soldiers were well versed in checkers, chess, dominoes, and card games, and travel versions of these games were often tucked into haversacks alongside sewing kits, journals, and photos from home. As an 1861 account of the Washington Artillery of New Orleans noted, “The men, when not on fatigue duty, lounge about, smoking, playing euchre, cribbage, or chess.”

The outbreak of war proved especially important for an entrepreneur named Milton Bradley. In 1860, Bradley had printed thousands of commemorative portraits of then-presidential-nominee

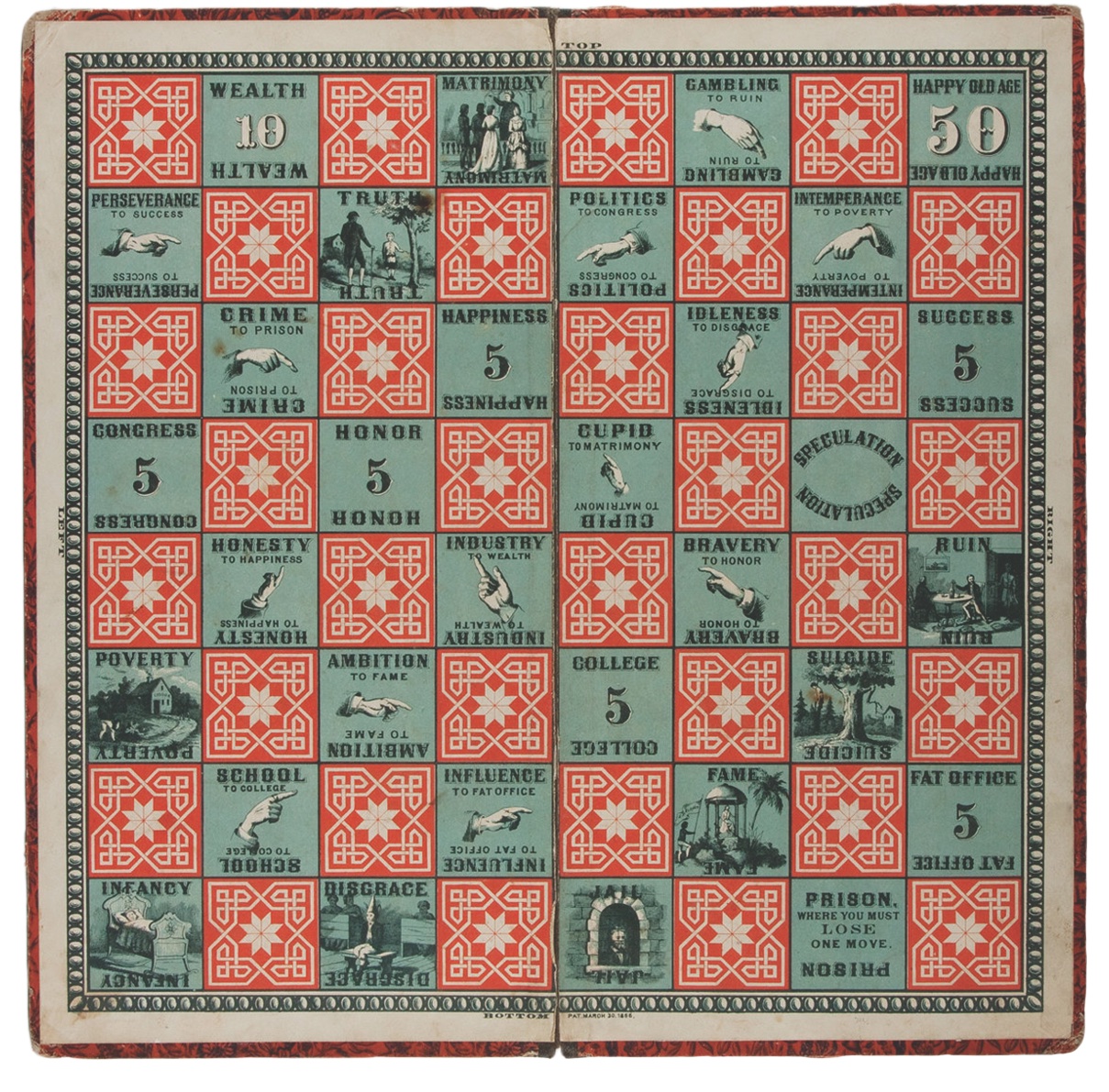

Abraham Lincoln. The portrait depicted an unbearded Lincoln as he had appeared during the campaign, but when the newly bewhiskered president was inaugurated, Bradley’s portraits were immediately obsolete. The misfire could have doomed Bradley if he hadn’t channeled his energy into a new board game he called The Checkered Game of Life, in which players endured ups and downs based on the spins of a teetotum, a top-like spinner that is the precursor to the plastic version that the game of Life uses to this day. Rather than earning prestigious jobs and fancy houses as in the current game, the original game had players achieving either “happy old age” or a host of terrible outcomes including jail, “intemperance to poverty,” and “gambling to ruin.” Bradley quickly realized that making the game portable for Civil War soldiers was a lucrative strategy; Bradley earned a patent for the game in 1866.

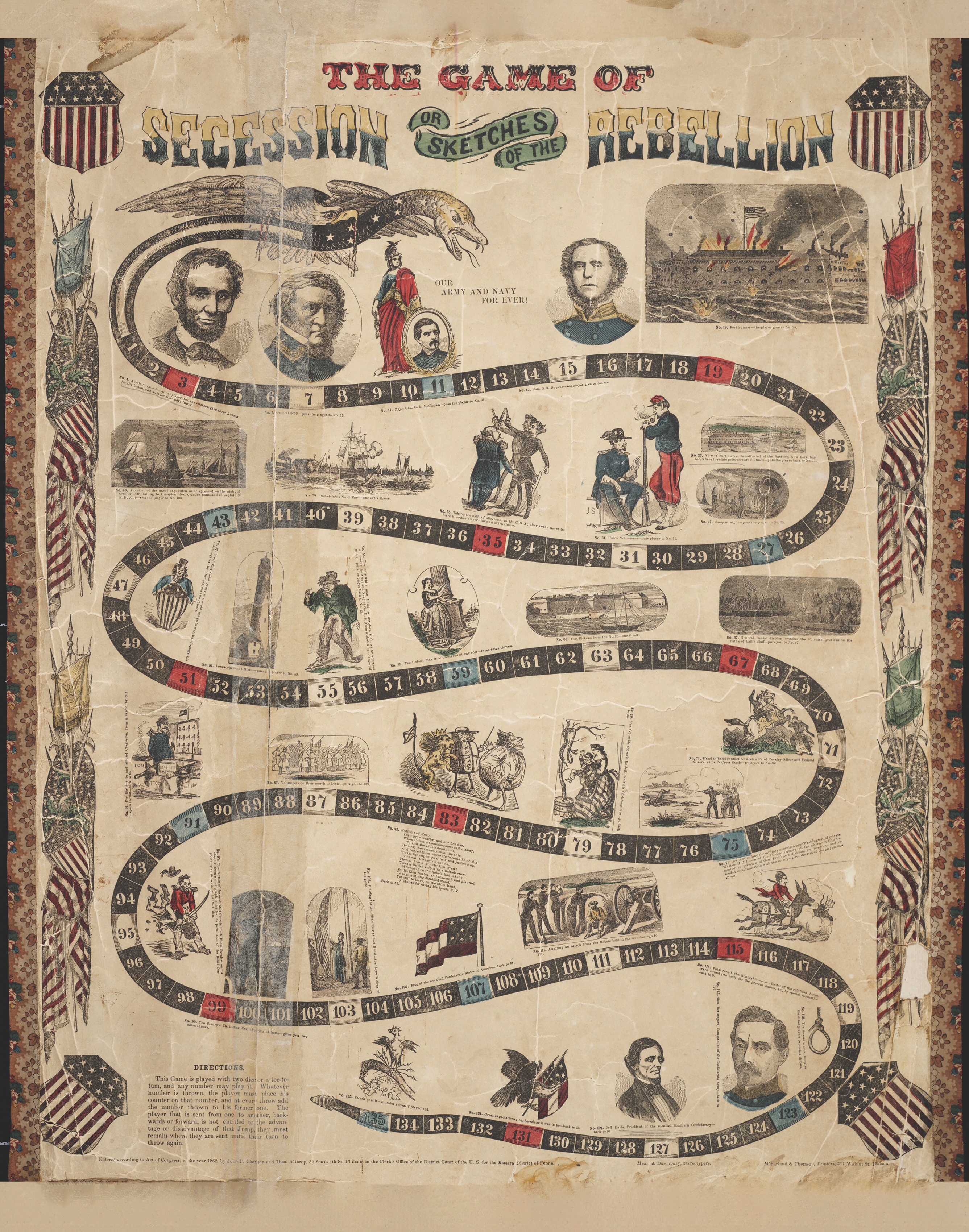

The war inspired other games as well. The New York State Library has a copy of a Chutes and Ladders-type game dating to 1862 called The Game of Secession, or Sketches of the Rebellion. Based on a die roll or the spin of a teetotum, players moved along a fork-tongued serpent divided into 135 spaces, with Union victories allowing advancement and Confederate victories signaling a retreat. The playing board depicts generals, soldiers, and both Lincoln and his counterpoint Jefferson Davis, along with key army and navy scenes. Land on spot number 79, illustrating the virtuous “Mrs. Columbia” holding “little Jeff Davis,” and you’ll have to go back a demoralizing 44 spaces. But land on space 59 bearing the slogan “The Union: may it be preserved at any cost!” and you’ll get three extra throws. (The game’s publisher, Charlton & Althrop of Philadelphia, also became known for printing pictorial envelopes depicting Union soldiers on them.)

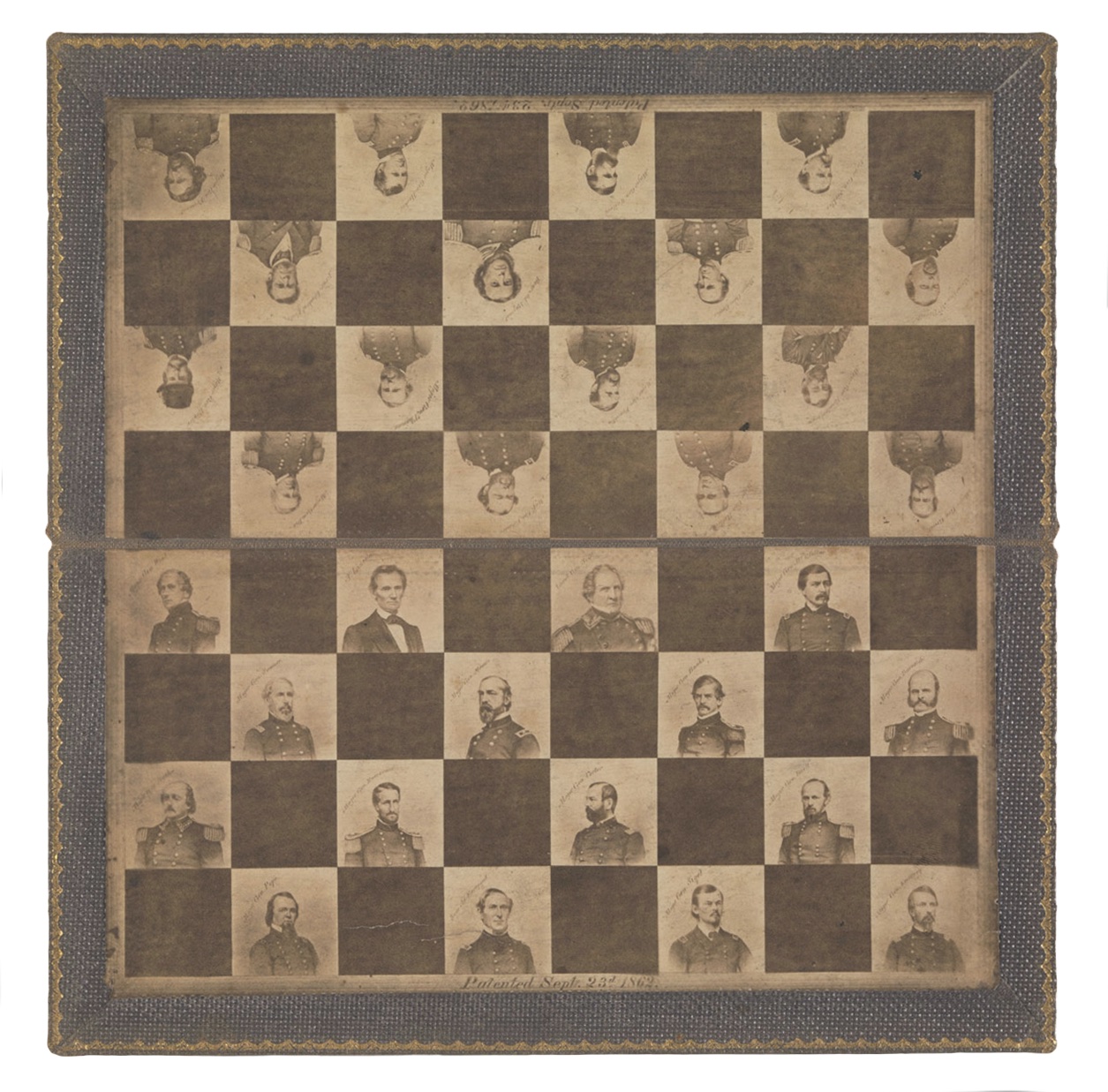

A checkered gameboard also dating to 1862, owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, features the portraits of 31 prominent Union generals in the light squares, including Ambrose Burnside, George McClellan, Benjamin Butler, and David Hunter (in a jaunty feathered hat), along with Lincoln. The Met notes that the board, measuring about 9 × 9 inches, could have been used by a soldier in camp, but “its construction and pristine condition suggest it was created, sold, and reserved for patriotic use at home.” A larger, 15 × 15 version of this gameboard sold at auction in 2019 for $3,500.

Rather than just “patriotic use at home,” by the 20th century and into the 21st, Civil War games were and are meant to be played. Board wargames arguably entered the modern era with the 1953 release of the game Tactics, the first title published by well-known gamemakers Avalon Hill. In 1958, on the eve of the Civil War centennial, Avalon Hill (which still exists today in name but under different corporate ownership) published the game Gettysburg, no doubt spawning a generation of Civil War enthusiasts and gamers. Among them was David A. Powell, a Civil War author and former game designer who lives outside Chicago. “My dad tried to play Gettysburg once and he put it away,” Powell says. “I found it in his closet and asked if I could have it. I now have about 400 wargames in my collection.”

Designed by pioneering game designer Charles S. Roberts, Gettysburg set important precedents in that different units in the game mimicked the actual size of the units on the battlefield in July 1863, and they had to enter the gameboard from the same routes their historical counterparts used, dealing with whatever advantage or disadvantage that created. The second edition of the game incorporated a hexagonal grid, which removed diagonal distortion in game play, since moving along the diagonal in a square grid covered more distance than moving across the sides. Hexagons make movement equidistant in all directions. Today, most wargames are based on either this method, called hex-and-counter, blocks (which represent units of various types), or cards.

“One of the things that interested me about wargames is they act as living maps,” Powell says. “When you read or write military history, everybody says, ‘I wish you had more maps.’ A wargame can provide you with a living map.”

Other successful companies followed Avalon Hill, including Game Designers Workshop (GDW), Simulation Publications Inc. (SPI), and Tactical Studies Rules (TSR), which exploded in the ’70s and ’80s on the strength of its roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons. In A House Divided, a GDW title first issued in 1981, the game is played on a mapboard of the 1860s United States, with boxes indicating a city, town, fort, or other military location. Rather than the simple “my roll, your roll” action of most board games, this game hinges on four actions per player turn: movement, combat, promotion, and recruitment. Restrictions exist, too: Only Union forces can move via the Potomac River, and the Confederacy doesn’t automatically win if D.C. is captured, but must meet other conditions, too. (And this is one of the simpler Civil War board games.) As S. Craig Taylor wrote in the book Hobby Games: The 100 Best, “It seems that some wargames are intended to be admired, and some wargames are intended to be played. A House Divided falls squarely into the latter category.”

Grant Dalgliesh, vice president of the veteran game company Columbia Games (founded by his father Tom Dalgliesh), says there are three types of wargamers: the competitors, the socializers, and the dreamers. “The dreamer pictures himself riding the horse,” Grant says. “My publishing style leans toward the first and second categories, but I don’t sacrifice those things that make the dreaming possible.”

Columbia’s Civil War titles include Bobby Lee, Sam Grant, Gettysburg: Badges of Courage, Shenandoah: Jackson’s Valley Campaign, and Shiloh: April 1862. Founded in 1972, the company pioneered the hardwood block method that is now commonplace in wargaming. Blocks allow for the “fog of war” element many gamers desire, where players must commit their forces without knowing exactly what their opponents’ assets and strengths are. Blocks stand upright on the board facing the owning player; a number on the top edge represents the brigade’s or battalion’s strength. As they take hits, blocks are rotated so that diminishing numbers are shown, until they’re completely eliminated.

Like reenacting, Civil War board gaming allows enthusiasts to examine history in a way that feels sustained and immersive. “I’m attracted to what the hobby calls ‘monster’ games—multiple maps, days, weeks, months to game, 50- to 100-page rule books,” David Powell says. “[Those games are] an effort to make you feel how you feel when you’re reading a book about Gettysburg.”

Back at Prezcon, it’s the end of a long day of gaming. Greg Gordon looks a little weary, but pleased. In addition to playing, he has served as the gamemaster for the Battle Cry tournament, which means he has spent hours monitoring wins and losses, answering questions, and keeping several concurrent games on track. Something like what a general officer would do on the battlefield, but on a smaller scale and with much lower stakes.

With remaining players dwindling, the contest has grown more intense. Gordon notes the people crowding around: players who have long since lost their own games; dutiful, patient spouses; gamers who’ve wandered over from other areas of the convention—all waiting for the outcome. “This game is very visual,” he says. “It adds to the whole experience.”

Something else holds them there, too—that inimitable feeling when you’ve found the people who enjoy your hobby as much as you do, the people who will sift through rulebooks and play for hours, just to claim a bit of this defining era of history for themselves. Far too soon, they know they will have to pack up their armies and move on.

Kim O’Connell is a writer based in Arlington, Va., with bylines in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Atlas Obscura, National Parks Traveler, and other national and regional publications.