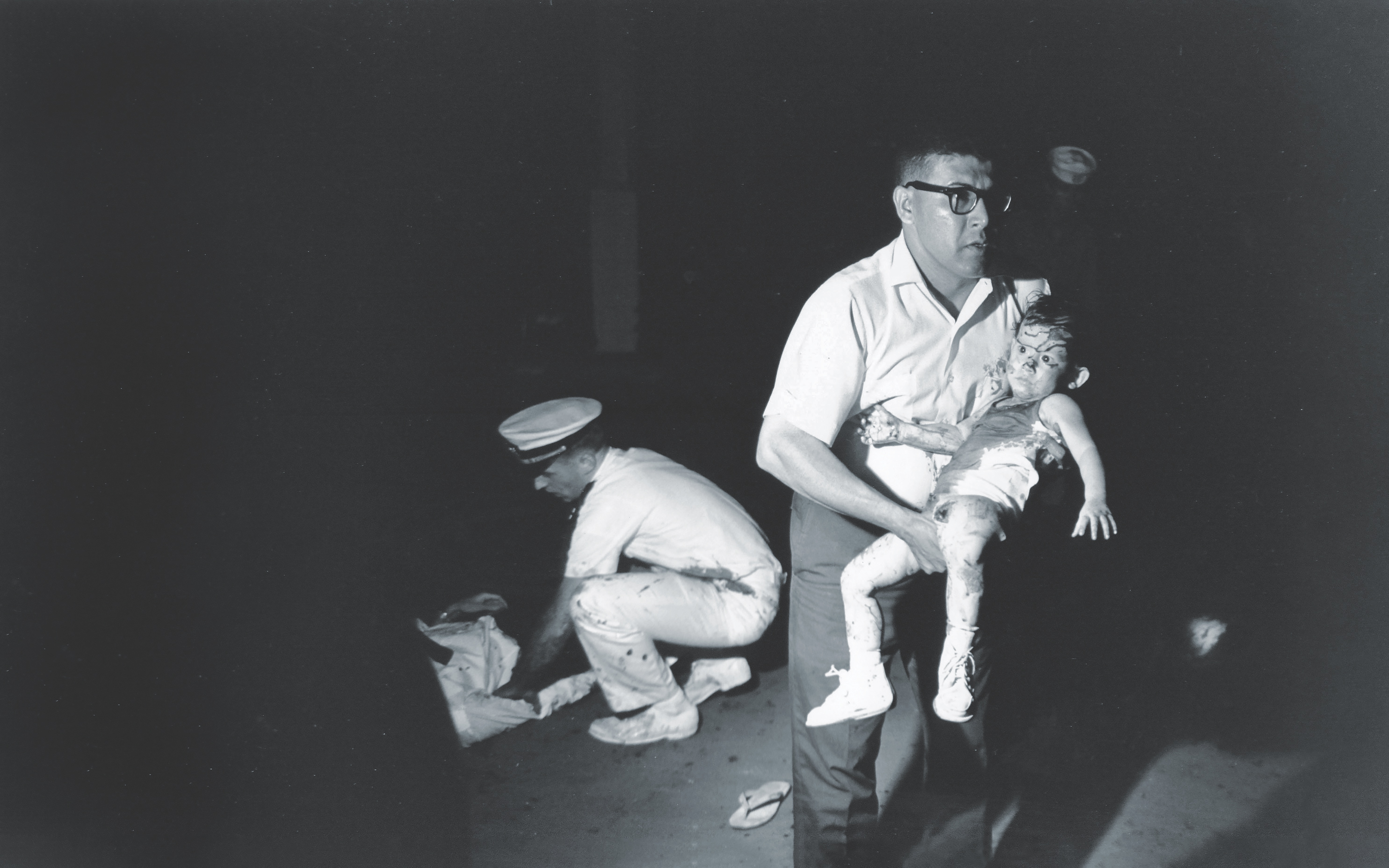

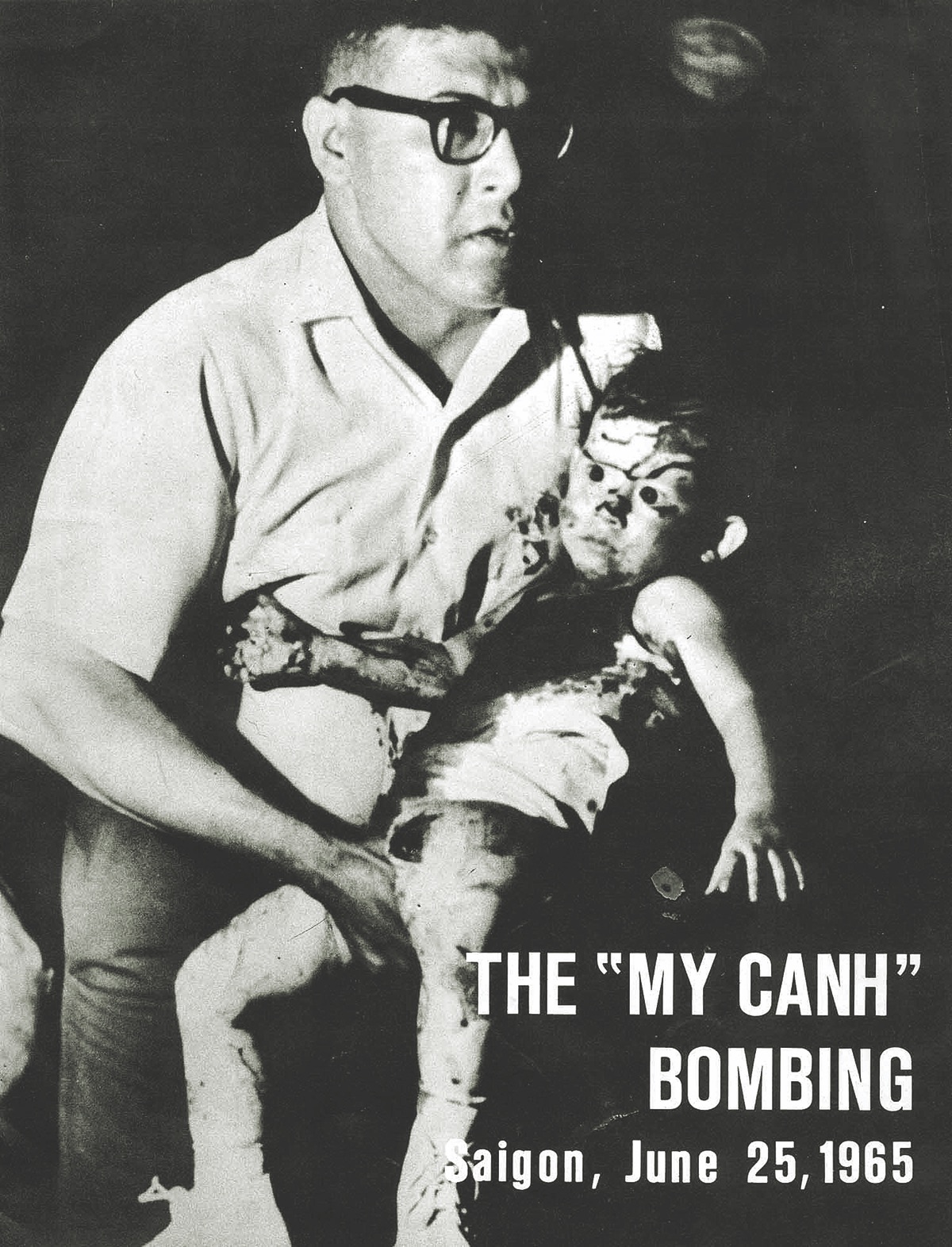

A bloodied child became the symbol of horror when Viet Cong bombs exploded at a Saigon restaurant.

One of the most searing photographs from the Vietnam War is the terrifying image of a badly injured child being rescued by a man in civilian clothes after Viet Cong terrorists bombed the My Canh restaurant in Saigon on June 25, 1965. Symbolic of the war’s innocent civilian casualties, the picture appeared in several newspapers and a military publication, but later was overshadowed by the dramatic photograph of the “Napalm Girl,” a running 9-year-old child who had ripped the clothing off her burning skin after napalm bombs from a South Vietnamese air force plane struck her village on June 8, 1972. That photograph was shown on the front page of The New York Times. The My Canh photo was not in the Times.

The graphic My Canh photo was on the cover of a 16-page pamphlet issued by the Joint U.S. Public Affairs Office to focus attention and fix blame on the Viet Cong “atrocity,” a double bombing of the floating restaurant on the Saigon River. Total casualties exceeded 100, and the public affairs office listed more than 20 Americans killed or wounded.

The incident received extensive media coverage, with many photos of the carnage. However, relatively few people saw the military pamphlet, which had 17 pictures, including one showing a hospital visit by U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Taylor, seen comforting the toddler who was on the cover and incorrectly identified as a small boy.

I had written an in-depth story about the My Canh attack for Vietnam magazine (June 2016) and posted it to my blog, along with the pamphlet’s cover. Two and a half years later, this startling comment appeared on my blog: “The child was not a small boy as the Public Affairs Office claimed . . . but was a girl. I know this to be a fact because that child was me.” The girl’s Vietnamese mother, Tran Ngoc Oanh, was killed, along with her friend, Army Sgt. 1st Class Alfred Combs Jr., an adviser with Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, which oversaw U.S. forces in the country.

Through emails and a phone interview, I learned about the tragic life of this little girl. Her adult name is Aimee Bartelt, and she is living in Clifton Springs, New York. Now 56 and an American citizen, Aimee was not quite 2 years old at the time of bombing.

Aimee and her sister, who was not at the My Canh restaurant that awful night, were adopted in Vietnam by Combs’ friend, U.S. Army officer Robert Harry Bartelt. Five months after the bombing, the two girls—Aimee’s sister is exactly two years older—came to the United States on a ship.

They lived with Bartelt and his family, including a grandmother who had a major role in raising them, at Fort Bragg, outside Fayetteville, North Carolina, for much of their youth, except for two years in Thailand when their father was stationed there. Aimee moved to New York state in 1987. She lived in a couple of cities there before settling in Clifton Springs, her home for more than 20 years.

Aimee still lives with the crippling injuries she suffered from the bomb blast. “Shrapnel went through my left thigh, which did considerable nerve damage below my knee,” she said. “My muscles are atrophied.” The gaping wound is clearly visible in the picture. Aimee had multiple surgeries and wore a leg brace until she was 10.

Aimee believes she was caught in the first explosion, and although she has no lucid memories of the incident, she is plagued by haunting images and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. “Sometimes I’ll see a light, a flash behind me that kind of lights up the room and be terribly afraid,” she said. “I imagine it’s the blast. That’s what my fear tells me.”

There were two Viet Cong assailants who carried out the bombing. One of them shared his story in 2010 in the People’s Army, a publication of Vietnam’s Defense Ministry. Huynh Phi Long said he and Le Van Ray were with the Viet Cong’s 67th Commando Unit in Saigon.

One of them arrived on a bicycle, and one rode a motorcycle. The explosives they carried were two powerful electronically detonated mines set to explode in succession and throw projectiles over a wide area.

The initial blast sprayed the My Canh, and the second one was aimed at the gangplank to hit panicked customers as they ran from the restaurant barge. The terrorists escaped on a getaway motorcycle before the first bomb detonated.

The victims represented at least six nationalities, but most were Vietnamese: police officers, an army captain, the driver of a cyclo (three-wheeled bicycle taxi), a variety of vendors, a dressmaker, a Vietnamese singer and numerous children.

Radio Hanoi, a propaganda station broadcasting to American troops, described the raid as “a new glorious exploit . . . dealing an appropriate blow to the U.S. aggressors.” A radio propagandist also issued this ominous warning after the My Canh attack: “You can get killed here. Get out while you’re still alive and before it’s too late.”

Ironically, the words My Canh translate into “beautiful view.” The restaurant was not seriously damaged and reopened five days later, according to the U.S. military pamphlet. It continued to serve Vietnamese, Chinese and seafood dishes through the end of the war before it closed permanently.

Ten years after the bombing, while young Bartelt watched TV coverage of the April 1975 evacuation of Saigon as the communists completed their conquest of South Vietnam, she started seeing flashes of dead bodies. “I knew the U.S. was withdrawing, and to me it was the same as being told that the Vietnamese weren’t worth it,” she recalled. “The images of children being crammed onto helicopters—it broke my heart and made me think that the same thing was happening to them, like the picture of me being taken away by the man, and my mother being left behind.”

Aimee also remembers a disturbing incident while horseback riding with a friend when she was in junior high school in Fayetteville. “I was being bounced around on a horse and had a flashback that I take as being carried out by that man.”

The name of “that man” was a mystery to Aimee for decades. But in 2018, she thinks it was, Aimee recognized him in a photo online and saw his name in the caption. He was identified as Army Maj. Abel Vela. I had also seen his name in an online caption. An internet search turned up a hopeful link to the University of Texas at Austin, where I discovered that the journalism school had interviewed Vela for its Voces Oral History Project, which focuses on notable Latinos in America. I was given his phone number in San Antonio.

I called Vela on the 54th anniversary of the bombing. After a military career spanning 27 years, he and his wife, Angela, went into business operating McDonald’s franchises in the San Antonio area. As a young boy in Texas, Vela worked in the cotton fields with his immigrant parents from Mexico. He was one of the Army advisers sent to South Vietnam by President John F. Kennedy in 1962.

On the night of the My Canh explosions, Vela was waiting across the street to meet friends for dinner at the restaurant when the first bomb detonated, he told me. He jumped into action. Vela had begun rescuing the injured when the second explosion went off. “I got involved with saving as many GIs as I could,” he said. “A horrible night, something you live with all the time.” The family still has a telegram from the Army informing Angela Vela that her husband suffered a wrist laceration, was treated and returned to duty.

Little Aimee was the last victim Vela reached. She was buried underneath another body. “The only thing I saw was a foot shaking and moving,” Vela said. “We got on the same military jeep. I wanted to take care of her. My wounds weren’t that bad.”

In 1970, Vela was stationed at Fort Bragg while Aimee’s father, then a Special Forces colonel, was there. Bartelt was Vela’s commander in the Special Forces. The Velas didn’t know that the

Bartelts were raising the girl rescued from the restaurant bomb explosion, and the Bartelts didn’t know Vela was the one who saved her life. A third person discovered the connection and brought

the men together.

When Abel and Angela Vela were invited to a social event at the home of Robert and Noemie Bartelt in Fayetteville, they were told not to talk to the kids. The Bartelts didn’t want to upset Aimee, who was not yet aware of the details surrounding her early life in Vietnam. When Aimee was 8 years old she discovered the Public Affairs Office pamphlet in her mother’s closet and began to figure things out on her own.

On the night of the party, the Velas spotted the young girl from a distance. “My husband recognized her because she was walking with a limp,” Angela recalled. “He remembered that when he picked her up [at the bombing scene], her little leg almost fell off.” Aimee said she was never told about this stealthy meeting. “It was chilling that that happened,” she said after I informed her.

In June 2019, Aimee made an emotional phone call to wish Vela “happy birthday.” He turned 93, and it was the first time they had ever talked. “I was so touched and moved,” she said. “Angela told me they had remembered me all these years. Meeting Abel on the phone and knowing that he was alive, and hearing about details of that night, kind of catapulted me to the land of the living.”

The My Canh survivor had come across my 2016 article as she investigated the calamity for a novel she is planning to write, preferring a fictionalized account so she can have a happy ending. “I’ve looked at a lot of pictures from that night, and they are very gory, hideous pictures,” Aimee said. “It wasn’t until I started doing my recent research that I began to understand the magnitude of devastation of that night.”

The Vietnam magazine article also answered her questions regarding the enemy’s motive. It noted that the 2010 People’s Army article said the bombing was a revenge attack for the public execution of Viet Cong commando Tran Van Dang, shot five days earlier by a South Vietnamese firing squad near Saigon’s central market.

Additionally, a Vietnamese-written history of Viet Cong commandos indicated that the My Canh restaurant had been branded a CIA gathering place and claimed that 51 intelligence officers were killed in the bombing. In the bomber’s interview with People’s Army, he identified the restaurant owner as “a trusted intelligence lackey of the CIA.”

For Americans who were in wartime Saigon, the My Canh remains a durable memory—a nice restaurant where they dined, the site of Saigon’s most vile terrorist incident, or the place where they were near-casualties themselves.

A young Army officer, Capt. Norman Schwarzkopf, almost went to the My Canh that Friday evening. Instead, he had dinner across the street on the rooftop of his hotel, the Majestic. After the first explosion, Schwarzkopf, who would climb the ranks to become commander of U.S. forces during the 1991 Gulf War, looked down in time to see the second blast hurl fleeing customers into the river.

Armed forces radio announcer Adrian Cronauer and three friends had just left the restaurant after dinner and witnessed the immediate aftermath. The bombing was loosely depicted in a Hollywood movie about Cronauer, Good Morning, Vietnam, starring comedian Robin Williams.

Although the explicit photos from that night are gruesome, Aimee, surprisingly, finds comfort in them. “My early years were nothing but different black-and-white depictions of the same media images displayed over and over,” she said. “I know it sounds unusual that I didn’t find them disturbing, but I felt a sense of belonging with the people there that night.”

Because of the cathartic phone call with Vela and the research for her book, Aimee is finally learning to let it go. “For the first time in my life I am seeing my young existence as truly real,” she said. “The My Canh bombing was real. That night was real. Now I feel like Pinocchio the morning he woke up, fully realizing, ‘Holy crap, I’m a real kid!’ I am so lucky to know this.”

Her struggles are not over. “I live four blocks away from a hospital, so a lot of times they have mercy flights with helicopters coming in,” she said, “and sometimes at night I hear them flying over and they scare me so terribly, and I want to panic.”

Aimee has never been back to Vietnam, where she surely has maternal relatives. She thinks she was born in Saigon and has been told that her birth father was a French pilot. Aimee has a son who lives in North Carolina.

Vela’s Army career included service at the end of World War II, when he participated in another agonizing rescue: the freeing of Jews from concentration camps.

“They walked out and started eating grass, the bark of the trees, whatever they could find,” Vela told oral history interviewer Nora Frost.

The My Canh bombing wasn’t Vela’s only brush with death in Vietnam. He was nearly killed in a mine explosion when the South Vietnamese unit he was advising came under fire. As the men ran for cover, Vela stepped on a mine and took shrapnel, while escaping the main thrust of the blast.

Looking back at his Army career, he says simply, “I’m proud that I was able to continue to serve my country.” His wife of 70 years, Angela, adds, “All my children know about Aimee. We have prayed about the situation and about the little girl all through these years.” Aimee was told she could consider the Velas like her own family.

Aimee has spent the past eight years on a rescue mission of her own: She has been serving on the board of Seneca White Deer Inc., a nonprofit that helps preserve a herd of rare white deer on the former Seneca Army Depot in New York. “The deer would never have survived without the protective fence surrounding the munitions base,” Aimee explains. “So it turns out that both those deer, and this war baby, would not be in this world if there were no such thing as war.”

Rick Fredericksen served as a Marine newsman at the American Forces Vietnam Network and was at the My Canh restaurant when it was shelled in 1969. The barge shuddered but the mortars missed their mark.

This feature originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. To subscribe, click here.