Through his public murals Colorado artist Fred “Lightning Heart” Haberlein related stories unique to the locales in which he painted, including La Jara, Manassa, Alamosa, Antonito, Glenwood Springs and Carbondale. The greatest concentration of his 140 murals are in the San Luis Valley of southcentral Colorado, though aficionados of his work can search out others in Arizona, New York and Oregon and as far away as Quito, Ecuador.

Haberlein, who succumbed to esophageal cancer on April 16, 2018, was born in Tulsa, Okla., on Dec. 7, 1944, and grew up in the San Luis Valley in the 1950s after his petroleum engineer father left the west Texas oil fields to open a hunting lodge named Conejos Ranch in Conejos County, Colo. Fred received his formal education from a community of Benedictine nuns in the small Hispanic community of Antonito, received a degree in sculpture and anthropology from Colorado State University and studied printmaking in graduate school at Arizona State.

While living in southern Arizona he connected with the Pascau Yaqui Indians, who recognized his strong spirituality and embraced him

With the counterculture of the 1960s in full swing, Haberlein joined a group of “right-brained” kindred spirits in the desert near Oracle in Arizona’s Pinal County where they converted an abandoned guest ranch into an art colony. There for the next 11 years Haberlein explored all genres of art, his passion for painting murals slowly emerging. In 1977 he painted his first mural, Desert Night, on the side of Mother Cody’s Café in Oracle.

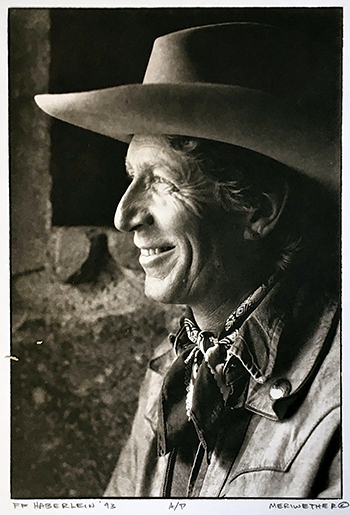

While living in southern Arizona he connected with the Pascau Yaqui Indians, who recognized his strong spirituality and embraced him. Invited to join in their 1972 Easter ceremony (a mix of traditional Yaqui and Catholic traditions), Haberlein scaled the Yaquis’ sacred Baboquivari Peak and earned the name Lightning Heart. “They felt my heart was like lightning, bright with love, ready to be shared wherever I went,” Haberlein once said. He often signed his art “Lightning Heart,” and to the front of his pickup truck he attached a rendering of a heart struck by a bolt of lightning. In 1984 he returned to Conejos Ranch to live and create more murals, but he returned every year to participate in the Yaqui Easter ceremony, the last time just two weeks before his death.

Haberlein’s widow, Teresa Platt, recently told Wild West that Fred preferred working in oils and for 18 years also taught acrylics and watercolors at the Colorado Mountain College campuses in Glenwood Springs and Aspen. By the time the couple moved to Glenwood Springs in 1988, Fred had completed 80 murals in the San Luis Valley. Perhaps the most ethereal is one of the valley he painted in 1985 inside the Alamosa post office. “It literally takes your breath away,” Teresa says. The 4-by-48-foot mural wraps around and above the post office boxes, stretching the full length and width of the room. You can feel the chill of the wind portrayed in the mural as it sweeps from the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan mountains out onto the valley floor, where it washes through chico (greasewood) and rabbitbrush and across the white blotches of alkali.

On the south edge of La Jara, along Highway 285, Haberlein paid homage to mustangs in his mural The Wild Horses, which covers the west-facing wall of the La Jara Trading Post. On an adjacent building stands his mural The Rams, a nod to the sheep ranchers who first settled the area in the early 1820s. Gracing a brick silo farther south on Highway 285 is Haberlein’s Whooping Crane, forever passing over the San Luis Valley along a major flyway.

Antonito is home to some two-dozen of its native son’s murals. Spanning four big silos is History of the San Luis Valley, a tribute to the successive cultures who dwelled here. Among Haberlein’s more ambitious creations, History of the Conejos River Region stretches along a building adjacent to the Railroad Hotel on Main Street; he painted it for the 1984 Summer Olympics torch relay. Also on Main Street is his 2016 mural depicting Our Lady of Guadalupe (aka Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), a Catholic icon and national symbol of Mexico. It suggests the lasting impact those Benedictine nuns had on the young artist back in 1950s Antonito. WW