The breathtakingly sleek Lockheed F-104 Starfighter was designed for a purpose that was too far ahead of its time

Few aircraft have left such contradictory impressions as the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. Many expert fighter pilots regarded the F-104 as the most exciting airplane they ever flew, and its spectacular appearance and performance gave rise to the title “the missile with a man in it.” To others, however, the F-104 was perceived as an unforgiving killer, and it became known by such unflattering nicknames as “the Widowmaker” and “the Mach-2 Mistake.”

In its time the F-104’s performance was second to none, setting new standards for speed, altitude and rate of climb. Yet its combat career was disappointing, and it was one of the few American combat aircraft to achieve far greater success abroad than in its country of origin. In fact, the Starfighter would probably be judged a failure were it not for the large number of them that were built and operated overseas.

The story of the F-104 began during the Korean War. Clarence L. “Kelly” Johnson, then chief designer at Lockheed’s Special Projects Division, the famous “Skunk Works,” visited frontline squadrons in 1952 to determine what characteristics the next generation of U.S. Air Force fighter planes should possess. At that time the Republic F-84 Thunderjet and North American F-86 Sabre were being outperformed by the Soviet-built Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15, particularly at high altitudes. Predictably, the reaction of the pilots was a demand for greater speed, altitude and rate of climb, even at the expense of maneuverability, armament, range, ease of maintenance and creature comforts.

Johnson returned to Lockheed with the notion of a lightweight, fast-climbing, high-speed, high-altitude, daylight interceptor. The idea was not exactly a new one, but in pursuing it Johnson was leading Lockheed onto financially risky ground. The concept of the specialized interceptor had been explored from time to time since World War I, and it had usually been discredited. The problem lay in the interceptor’s lack of operational flexibility. No one wanted a combat plane that performed one mission well to the exclusion of all other missions. Curtiss-Wright, for example, had built an interceptor-fighter in 1939 called the CW-21 Demon. Touted as the fastest-climbing fighter in the world in its day, the CW-21 prototype was not accepted by the U.S. Army Air Corps. A few CW-21Bs were eventually exported to the Dutch East Indies, where Japanese fighters made short work of them in 1942.

Johnson was convinced, however, that he and his staff could produce such a quantum leap in aircraft performance that the Air Force would have to take notice. His confidence was founded on past achievements. Since the advent of the Lockheed Vega in the late 1920s, Lockheed aircraft had consistently displayed a combination of outstanding performance, technological innovation and aesthetic flair that had set them apart from all others. It was no coincidence that Wiley Post completed the first solo flight around the world in 1933 in a Lockheed Vega, or that it was a Lockheed Electra that Amelia Earhart flew on her ill-fated 1937 attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Nor was it coincidental that Howard Hughes selected a Lockheed Model 14 when he set a record flying around the world in 1939, or that he later backed the development of the four-engine Lockheed Constellation, the 1943 advent of which set a new standard for air travel. For the military, Lockheed had developed the P-38 Lightning, with its audacious twin-boom configuration, as well as the F-80 Shooting Star, America’s first successful jet fighter.

If one word could describe the airplane that Kelly Johnson and his team designed in 1952, it would be “extreme.” The Model 83, as the F-104 was originally known, was created for the sole purpose of flying faster and higher than any other fighter in the world. No airplane since the Gee-Bee R-1 racer of the early 1930s had been so blatantly designed to go fast at all costs. It was, in essence, the smallest fuselage and wings that could be constructed around the most powerful available engine, one pilot, and the minimum necessary fuel and armament. The F-104’s maximum airspeed of Mach 2.2 was dictated primarily by shock wave propagation in the air intakes, by the thermal limitations of the aluminum alloy from which the airframe was constructed and the amount of stress that the canopy attachment points could take—air pressure could pull it from the cockpit at speeds above Mach 2.2. To handle temperatures generated at higher speeds, the airframe would have had to have been built of titanium, rendering it far too expensive for mass production. Lockheed eventually had the opportunity to build a hypersonic aircraft out of titanium, the SR-71 Blackbird, in 1962.

The F-104 was the first aircraft to be powered by the then-new 14,800-pound thrust General Electric J-79, an engine that was to set a new standard for power-to-weight ratio. The J-79 later powered many other outstanding aircraft, including the Convair B-58 Hustler supersonic bomber, the McDonnell F-4 Phantom and the Israel Aircraft Industries Kfir. On one occasion a J-79 was even built into a car in order to set a land speed record.

The jet engine air intakes on the F-104 were fitted with movable semicircular shock cones designed to adjust the airflow at various speeds. Such devices became commonplace on jet planes in later years but were unheard of prior to the F-104. The shock cones were considered so secret that the engine air intakes were completely hidden under aluminum fairings when the Starfighter was first exhibited to the public on April 17, 1956.

The engine was not the only revolutionary component in the F-104. The plane’s principal armament of a single 20mm cannon may have seemed puny, but it was a very special gun. The Starfighter was the first aircraft designed to use the General Electric M-61 Vulcan cannon, a six-barreled, electrically operated Gatling-type gun that could fire an unprecedented 6,000 rounds per minute—a rate of fire that could use up the F-104’s complement of 725 rounds in just over seven seconds. Like the J-79 engine, the Vulcan cannon was to see a great deal of service in other aircraft, and it is still used today.

The Air Force was understandably dubious about the effectiveness of a gun fired from an airplane that was flying as fast as a bullet. Its operational requirement therefore stipulated that the F-104’s armament should be augmented with yet another new weapon system, the heat-seeking AIM-7 Sidewinder air-to-air missile. A single Sidewinder was mounted on a rail on each wingtip.

The Starfighter’s T-shaped tail was also unprecedented. The configuration was arrived at after evaluating no less than 285 different designs. Unfortunately, the state of ejector seat technology was not up to conveying the pilot over the T-tail safely at the speeds for which the F-104 was designed to fly. Lockheed’s solution was to arrange the seat to eject downward. Although the fighter was expected to operate mainly at high altitudes, the downward-firing ejector seat was a hazard to the pilot if trouble occurred at low altitudes, such as just after takeoff or during the landing approach. Pilots were advised to roll the F-104 inverted before punching out, but that was not always possible in an emergency. The ejector seat would later prove to be the aircraft’s single most controversial feature.

By far the most astonishing feature of the Starfighter was its wings. In an era of swept wings and broad delta wings, Lockheed broke with convention by giving the F-104 tapered wings of low aspect ratio that were remarkably small. Unlike most aircraft designs, the F-104’s wing format was chosen solely for efficiency at supersonic speed, without any consideration for lift, maneuverability or ease of handling at lower speeds. To compensate, the entire leading edges of the wings were designed to pivot downward to increase lift for takeoff and landing. Lift was also augmented by ingenious trailing-edge flaps that had high-pressure air vented from the engine blown across their upper surfaces. With a thickness at the wing root of 4.2 inches, a great deal of design ingenuity was necessary to develop aileron and flap actuators small enough to fit inside them. The edges were so sharp that special covers had to be installed over them to prevent ground crewmen from injuring themselves. Another unusual feature of the F-104’s wings that was not obvious from the outside was that they were not connected to each other by a continuous main spar, but by a frame encircling the fuselage.

There were penalties to be paid for the Starfighter’s speed. The tiny, thin wings that endowed the F-104 with its high performance also gave it a blistering stall speed of 198 mph. To help stop the Starfighter, Lockheed gave it a powerful drag chute. It also had a tail hook, similar to those found on carrier-based fighters but an unusual feature on a land-based fighter. Since the wings could accommodate neither fuel tanks nor landing gear, both had to share the limited space available inside the narrow fuselage. As a result, the F-104 was never to be noted for its endurance, even with extra fuel tanks fitted to the wingtips.

The F-104’s design also gave it a high wing loading, which rendered its maneuverability less than ideal, particularly at subsonic speeds. In the 1950s, however, it was generally believed that high-G, subsonic dogfighting would no longer be a decisive factor in future air battles, which would be fought at high-altitudes by supersonic fighter planes armed with guided missiles—aircraft such as the Starfighter. That supposition would be rudely contradicted in the coming decades over Vietnam, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent.

Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier flew the prototype XF-104 for the first time on March 4, 1954. The airframe was ready before the J-79 engine, so the XF-104 was first flown with a Wright XJ65-W-6 engine. Even though the J-65 only produced 10,200 pounds of thrust—31 percent less than the J-79—the XF-104 attained a speed of Mach 1.79 on March 25, 1955, becoming the first fighter to exceed 1,000 mph.

The XF-104 was eventually succeeded by 17 service-test YF-104As with J-79 engines. Although the YF-104As still presented many technical problems that needed to be ironed out, their performance was undeniably everything that Lockheed had promised. Kelly Johnson’s faith in the Starfighter concept was vindicated when the YF-104A became the first aircraft type to set both speed and altitude records. Major Howard Johnson climbed to an altitude of 91,249 feet on May 7, 1958, and four days later Captain Walter Irwin attained a speed of 1,404.19 mph. The aircraft also demonstrated an incredible climb rate of more than 60,000 feet per minute.

The Starfighter’s altitude performance was so impressive that Lockheed later built three NF-104As equipped with auxiliary rocket engines and reaction-jet controls, like those on a spacecraft, for operation at altitudes so high that conventional controls were no longer effective. They were used by the Aerospace Research Pilots’ School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Three other Starfighters, stripped of all armament and designated F-104Ns, were used as chase planes by the National Air and Space Agency (NASA) at Edwards AFB.

Apart from everything else, the F-104 was one of the most exciting-looking aircraft in the world in the mid-1950s, and it is still a head-turner four decades later. The Starfighter combined unparalleled performance with an appearance that was both extraordinarily beautiful and wholly original. In that respect, it was a typical product of the people who had created the P-38 Lightning and the F-80 Shooting Star. The first production fighter capable of exceeding Mach-2 in level flight, the Starfighter looked as though it were already doing so while parked. It was the closest thing the Air Force ever had to a Ferrari with wings and an afterburner, and every 1950s jet jockey was understandably eager to get his hands on one.

The U.S. Air Force ordered 155 production F-104As in 1955, a number that was raised to 722 in 1958. So many problems remained to be ironed out, however, that the first 35 fighters were diverted to the flight-test program. Computerized flight simulators were not yet available in the 1950s, so the Air Force also had to acquire 26 additional two-seat training versions. Designated F-104B, the trainer was fitted with a rear cockpit in the space normally occupied by the cannon’s ammunition bay.

It was not until January 1958 that the F-104As became operational with the 83rd Fighter Interception Squadron. By that time the new 20mm cannon, which had proved unreliable, had been removed from the Starfighters. An improved version did not become available for another six years. In the meantime, the F-104A’s sole armament was the pair of Sidewinder missiles. Problems were also encountered with the new engine, and several Starfighters were lost in accidents in the first few months. By April 1958, the F-104As had to be temporarily grounded pending the availability of an improved version of the J-79 engine.

In its original form, the Starfighter handled well at the speeds for which it had been designed. Jet-qualified pilot and artist Mike Machat flew solo in an F-104B trainer and considered it “one of the top three I have ever flown, light to the touch and with beautiful control harmony at 350 knots.” When it first entered service, however, the F-104A was regarded as a difficult plane to fly compared to other contemporary fighters, and its accident rate was proportionally higher. In seven years, 49 of the 153 that were eventually built were lost to accidents, a staggering 32 percent. The downward-firing ejector seat did not improve matters. Eighteen pilots were killed during the same period. In addition, operational experience with the F-104A was raising questions about its limited armament, range, maneuverability and versatility. The Air Force had begun to have second thoughts about the F-104A, and in December 1958 its order was reduced to 153. After only a year and a half of service with the Air Defense Command, the F-104As were reassigned to the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard. Many of them were later exported under the Mutual Assistance Program.

Lockheed responded to criticism of the F-104A with a more versatile fighter-bomber version. Designated F-104C, the improved Starfighter’s once-pristine lines were cluttered up with external hardpoints for up to 4,000 pounds of bombs, missiles and fuel tanks. The problem of the fighter’s short range was also addressed with the provision for an in-flight refueling probe. The U.S. Air Force bought only 56 F-104Cs, along with 21 F-104D two-seat trainer versions.

F-104Cs were used in Vietnam by the 435th, 436th and 476th squadrons of the 479th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) from 1965 to 1968, but Vietnam was not really a suitable venue for them. Since there was nothing for them to intercept, there was no opportunity for the Starfighter to be used to its best advantage. The closest the Starfighter came to air-to-air combat was on January 2, 1967, when flights of F-104Cs flew top cover for the McDonnell F-4Cs of Colonel Robin Olds’ 8th TFW during an attempt to lure North Vietnamese Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21s up to fight. Operation Bolo, as it was called, was a success, with the Phantom crews claiming seven MiGs (five of which were subsequently acknowledged in North Vietnamese records) without loss—and without the help of the Starfighters.

Starfighters often escorted Lockheed EC-212 radar planes over the Gulf of Tonkin, a tiring 7 1/2-hour mission that required no less than six midair refuelings. Flying fighter-bomber missions over Laos and South Vietnam, the Starfighter compared unfavorably in both range and weapon load with larger aircraft like the F-4 Phantom and the Republic F-105 Thunderchief. The F-104C also demonstrated that it was still as dangerous to its own pilots as the enemy was—the 435th Tactical Fighter Squadron lost five Starfighters to enemy action in Vietnam, but lost another six in accidents.

The F-104 would have ended its days in obscurity with the Air National Guard had it not been for a sales coup brought off by Lockheed’s marketing department. In 1958 West Germany, whose Luftwaffe had been resurrected two years earlier, was in the market for a supersonic multirole fighter. They wanted an aircraft able to perform air defense, reconnaissance, interdiction, close support, maritime strike and even nuclear bombing missions. Despite the fact that the Starfighter had been originally designed as a specialized interceptor, Lockheed managed to adapt it to meet all the Germans’ requirements as the F-104G. It incorporated a redesigned airframe, a more powerful version of the J-79 engine, a larger tail, an inertial navigation system, improved radar and five hardpoints for external stores.

Because the Bundesluftwaffe (Federal German Air Force) expected to use the F-104G largely as a low-altitude fighter-bomber, it adamantly rejected the Starfighter’s lethal downward-firing ejector seat. The Germans wanted to equip the plane with Britain’s superior Martin-Baker ejector seat, but Lockheed was equally insistent upon using an upward-firing seat of their own design. After 23 months of haggling, the Bundesluftwaffe acquiesced to Lockheed’s wishes. In 1967, however, the F-104Gs were finally retrofitted with the British seats.

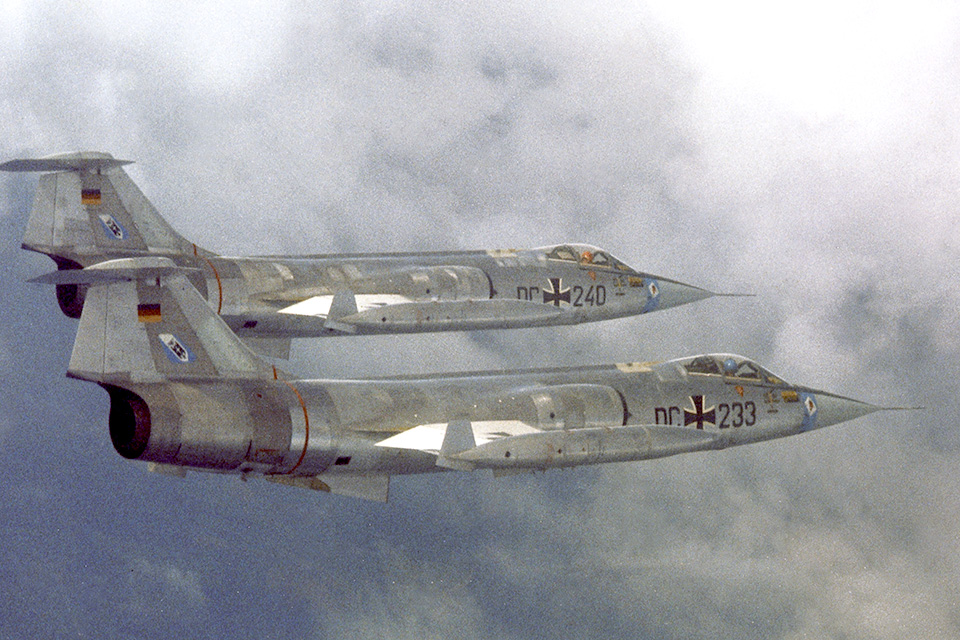

The first F-104G flew on October 5, 1960. Once the Bundesluftwaffe agreed to buy the Starfighter, many other air forces of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) followed suit in order to standardize their equipment. Over the course of the next two decades, it became one of the most widely used fighter types in the world. In NATO alone, Starfighters served in the air forces of Canada, Norway, Denmark, West Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Turkey and Greece. West Germany, the largest user, acquired more than 600 of them.

The West German government was also interested in resurrecting that nation’s aviation industry, which had been demolished during World War II, so it insisted on buying an aircraft that could be built under license. As other NATO nations joined West Germany in the F-104G production program, the Starfighter restored not only the nation’s aviation industry but also those of many other European countries. A vast international industrial network was set up to build them, involving no fewer than 17 companies in West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy. The F-104G became, for all intents and purposes, the first “Eurofighter.” In addition, a further 238 F-104Gs were manufactured in Canada by Canadair as CF-104s. A total of 1,585 F-104Gs and CF-104s were built, including two-seat conversion trainers. That was more than five times the number of Starfighters built for the U.S. Air Force.

The F-104 became as controversial in West Germany as it had been in the United States. The modifications made to the aircraft caused an increase in weight that raised the stall speed to 216 mph. As a result of the frequent adverse weather conditions over northern Europe, combined with the effect of all those added external stores on the F-104G’s airframe, the West German press reported Starfighter crashes with a frequency that became an embarrassment to the government. In 1965 alone, the Bundesluftwaffe lost 30 F-104Gs in accidents. In consequence, although most Americans were unaware of it, many Bundesluftwaffe pilots were flying their F-104Gs, disguised in U.S. Air Force markings, over the southwestern United States—where the weather was much better for training flights—during the 1960s and 1970s.

In addition to the European-Canadian production program, the Japanese also built and operated Starfighters. Unlike the multirole European version, however, the Japanese Starfighter, known as the F-104J, was optimized for air defense. Its armament consisted of the 20mm Vulcan cannon and four Sidewinders. Mitsubishi and Kawasaki built 210 F-104Js for the Japanese air self-defense force, as well as 20 two-seat conversion trainers.

The last production version of the Starfighter was the F-104S, an all-weather interceptor developed by Italy in 1968. Equipped with an uprated J-79 engine and more advanced avionics, the F-104S finally dispensed with the 20mm cannon. The former cannon bay now contained an electronics package enabling the plane to fire AIM-9 Sparrow air-to-air missiles, which it carried in addition to four Sidewinders, making it the most formidable of all the Starfighters. Aeritalia produced 205 F-104Ss for the Italian air force, plus an additional 40 for the Turkish air force. The last F-104S was completed in 1979, a quarter of a century after the flight of the first Starfighter.

Lockheed offered one final development of the F-104 in the late 1960s. Called the CL-1200 Lancer, it differed from the Starfighter in having a longer fuselage carrying more fuel, a larger, shoulder-mounted wing and a conventional, low-set tailplane. The Lancer came along too late to gain acceptance and never got beyond the mock-up stage.

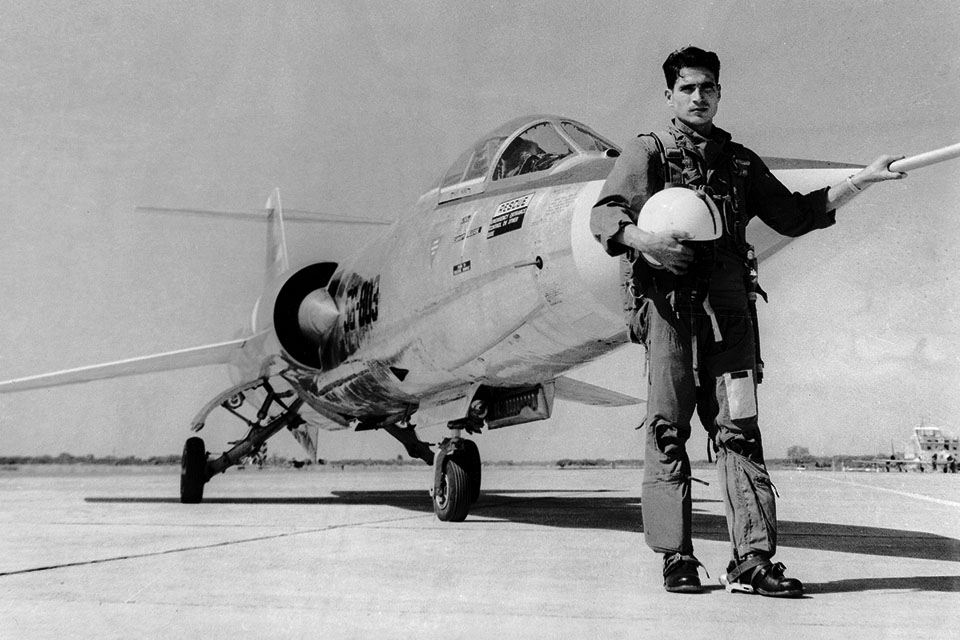

In addition to those built by NATO and Japan, surplus American F-104As found their way into the air forces of Jordan, Pakistan and Taiwan. F-104As and F-104Gs of Taiwan’s Republic of China Air Force claimed several victories in occasional clashes with reconnaissance and fighter planes from the People’s Republic of China. Apart from Vietnam, however, Starfighters saw their principal combat use with the Pakistan Air Force (PAF), which used them in two wars against India, in 1965 and 1971. The PAF’s experience over Kashmir was more significant than the U.S. Air Force’s over Vietnam because its F-104s were the first ones to engage in the type of air combat for which they had been designed.

Pakistan acquired its Starfighters as a direct result of the Soviet downing of an American Lockheed U-2 spy plane that had been based in Peshawar in 1960. Understandably annoyed at the Pakistanis for allowing the Americans to use their country as a base for espionage missions, the Soviets threatened to target Pakistan for nuclear attack if such activities continued. Taking the threat seriously, the United States agreed to provide Pakistan with enough surplus F-104A interceptors to equip one squadron.

Although the F-104As were intended to defend Pakistan against high-flying Soviet bombers coming over the Hindu Kush Mountains, their actual combat use would be under quite different circumstances. In the summer of 1965, a dispute involving sovereignty over the Vale of Kashmir—smoldering between India and Pakistan for many years—erupted into war. At that time the PAF had about 140 combat aircraft, mostly American-built, including the F-104As of No. 9 Squadron. Facing them was the Indian Air Force (IAF), with about 500 aircraft of mostly British and French manufacture. The IAF had also begun to acquire MiG-21Fs, new Soviet interceptors capable of Mach 2, but only nine of them were operational with No. 28 Squadron in September 1965, and they saw little use.

The war, which lasted from August 15 to September 22, 1965, did little for either side except waste lives and materiel. Pakistan used the F-104As primarily for combat air patrols, usually consisting of two Sidewinder-equipped F-86F Sabres, with a Starfighter to provide top cover. The F-104s occasionally provided escort to PAF Martin B-57B Canberra bombers or reconnaissance aircraft and sometimes flew high-speed photoreconnaissance missions themselves.

Indian pilots were initially intimidated by the formidable reputation of Pakistan’s Mach-2 interceptors. In their first aerial encounter on September 3, two PAF F-86s battled six IAF Hawker Siddeley Gnats while an F-104A, flown by Flying Officer Abbas Mirza, darted around above, vainly trying to get a shot at one of the elusive Gnats. When a second F-104A arrived, however, one of the Gnats, flown by Squadron Leader Brij Pal Singh Sikand, suddenly descended and landed on the airfield at Pasrur.

The first air-to-air victory by an F-104—or by any Mach-2 airplane—came on September 6, when Flight Lt. Aftab Alam Khan, disobeying orders by descending below 10,000 feet, downed one Dassault Mystère IVA fighter-bomber with a Sidewinder at an altitude of 5,000 feet and damaged a second. During attacks on Rawalpindi and Peshawar by IAF English Electric Canberras that night, three F-104s tried to intercept them but failed to get a target acquisition because the bombers were too low. During an Indian attack on Sargodha air base, however, Flight Lt. Amjad Hussein Khan used his cannon to destroy a Mystère IVA, killing Squadron Leader A.B. Devayya of No. 1 Squadron, IAF. Debris from the exploding Mystère struck the Starfighter, however, and Amjad was forced to eject at low altitude. He had reason to be grateful that his F-104 did not have the original downward-firing ejection seat—otherwise, his subsequent award of the Sitara-i-Jurat would probably have been posthumous.

On the night of September 13-14, Squadron Leader Mervyn Leslie Middlecoat achieved the first blind night interception in an F-104, firing a Sidewinder at a Canberra from a distance of 4,000 feet and reporting an explosion, but failing to obtain a confirmation. Another Starfighter was lost on September 17, when Flying Officer G.O. Abassi tried to land in a sudden dust storm, undershot the runway and crashed in a ball of fire. Miraculously, he was thrown clear, still strapped in his ejection seat, and survived with only minor injuries.

On September 21, in the last days of the war, Flying Officer Jamal A. Khan finally got to use the Starfighter in the manner for which it had originally been designed, scoring a solid Sidewinder hit on a Canberra at 33,000 feet over Fazilka. The Indian navigator was killed, but the pilot, Flight Lt. M.M. Lowe, bailed out and was taken prisoner.

During the course of the Kashmir War, No. 9 Squadron flew a total of 246 sorties, of which 42 were at night. The F-104As gave a good account of themselves on the whole, but criticism was raised over their insufficient maneuverability, lack of ground-attack capability and the inefficiency of their radars at low altitudes. The Pakistanis had actually gotten a lot more value out of their older Sabres, which could be used for both air combat and ground attack.

Hostilities again broke out between India and Pakistan on December 3, 1971, this time over the secession of East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. Once again, the IAF outnumbered the PAF by nearly 5 to 1. More significant, however, the qualitative advantage enjoyed by the PAF in 1965 had been considerably reduced. For all intents and purposes, the F-104A had been the only supersonic fighter in service over the subcontinent in 1965. Since then, India’s Hindustan Aeronautics, Ltd., had been producing improved model MiG-21FLs under license. By 1971, the MiG-21 had become numerically the most important fighter in the IAF, with 232 in service, enough to equip nine squadrons. In addition, the IAF had six squadrons of Soviet-built Sukhoi Su-7BM supersonic fighter-bombers.

Pakistan had managed to acquire enough F-104As from the Royal Jordanian Air Force to keep No. 9 Squadron operational, but the Starfighter was no longer Pakistan’s only supersonic fighter. By 1971, the PAF had three squadrons of French-built Mirage IIIEJs and three squadrons of unique Shenyang F-6s—illegal Chinese copies of Russia’s supersonic MiG-19F, which the Pakistanis had improved with British Martin-Baker ejection seats and American Sidewinder missiles. In addition, the Pakistanis had replaced their older model F-86Fs with five squadrons of a far more potent version, the Canadair Sabre Mark 6, acquired via West Germany and Iran.

The air war began in earnest on December 3, when the PAF launched strikes against 10 Indian air bases but failed to eliminate the IAF with that one blow. When the IAF struck back the next day, No. 9 Squadron’s F-104As downed a Gnat and an Su-7 over Sargodha. During an attack on the radar installation at Amritsar on December 5, No. 9 Squadron suffered its first loss of the war to anti-aircraft fire. Flight Lt. Amjad Hussein Khan ejected from his F-104 and was taken prisoner. Wing Commander Arif Iqbal scored an unusual Starfighter victory during a raid on Okha Harbor on December 10, when he downed a land-based Bréguet Alizé turboprop anti-submarine patrol plane of the Indian navy over the Gulf of Kutch.

A particularly significant air battle took place on the afternoon of December 12, when a pair of F-104As tried to strafe the Indian airfield at Jamnagar and were themselves attacked by two MiG-21FLs of No. 47 Squadron, IAF. One F-104 fled northward, and the other sped southwest over the Gulf of Kutch with Flight Lt. Bharat Bhushan Soni in pursuit. Applying full afterburner to his MiG, Soni fired a K-13 missile, but the F-104 evaded it and then turned sharply to the right. Cutting inside the Starfighter’s turn and closing to 300 meters, Soni fired three bursts from his GSh-23 cannon, then watched the stricken plane pull up. The pilot ejected and parachuted into the shark-infested Gulf of Kutch. Soni called for a rescue launch, but no trace of his opponent, Wing Cmdr. Middlecoat, a decorated veteran of the 1965 war, was ever found. The Starfighter had clearly been unable to outaccelerate or outturn the MiG-21 at low altitude. It was equally clear that Indian pilots were no longer intimidated by the F-104.

That fact was demonstrated again on the last day of the war, December 17, when No. 9 Squadron’s Starfighters clashed with MiG-21s of No. 29 Squadron, IAF. Squadron Leader I.S. Bindra claimed an F-104, though in fact it escaped with damage. In a later fight over Umarkot, Flight Lt. N. Kukresa made a similar premature claim on an F-104, but when he was attacked in turn by another Starfighter, Flight Lt. A. Datta blew it off his tail, killing Flight Lt. Samad Ali Changezi. Interestingly, while no MiGs were downed by Starfighters during the war, one was reportedly shot down by an F-6 on December 14, and another MiG-21 lost a dogfight with a Sabre flown by Flight Lt. Maqsood Amir of No. 16 Squadron, PAF, on December 17—the Indian pilot, Flight Lt. Harish Singjhi, bailed out and was taken prisoner.

The 1971 Indo-Pakistan War was followed with great interest by aviation experts throughout the world. The Starfighter was still the mainstay of most of the NATO air forces at that time, and for years there had been a great deal of conjecture about how the Lockheed fighter would fare against modern Soviet equipment. Admittedly, the F-104Gs and F-104Ss used in Europe were far more potent then the elderly F-104As operated by Pakistan. There could no longer be any doubt, however, that the Starfighter was no match for the MiG-21, particularly in maneuverability.

Despite the disappointing performance of the PAF’s F-104As, the NATO air forces continued to rely heavily on the Starfighter throughout the 1970s. The Italians, in particular, regarded their Sparrow-equipped F-104S as one of the most formidable air-defense fighters in the world. Nevertheless, the F-104’s days as a first-line combat aircraft were clearly numbered. In the early 1970s, the Europeans began developing an aircraft of their own to replace the aging Lockheed design.

It is interesting to compare the characteristics of the F-104G with those of the Panavia Tornado, which eventually replaced it. Unlike the Starfighter, the Tornado was designed from the outset as a multirole aircraft. A larger aircraft with twin engines, the Tornado has more than double the combat radius and carries five times the payload of its predecessor. Where the F-104 was originally designed for maximum speed and altitude, the Tornado is optimized for low-altitude performance. In addition, its two-seat layout endows it with far greater operational versatility than the Starfighter, and its swing-wing design enables it to fly well at both high and low speeds. The design concepts of the Starfighter and the Tornado are, therefore, almost diametrical opposites.

The F-104 was the product of a period when air combat was expected to be waged at ever higher speeds and altitudes. Whatever faults the aircraft had are directly traceable to that early 1950s philosophy. By the time the Starfighter became operational, that trend had begun to reverse itself. Today air combat is often carried on just above the ground. Considering the fact that it had originally been intended as a specialized interceptor of high-flying bombers, Lockheed did a remarkably good job of adapting the F-104 into a multirole Eurofighter.

The F-104 deserves a place in the pantheon of American aviation achievements as the first combat aircraft to fly at double the speed of sound. It also deserves recognition for the part it played in NATO’s air defense during the Cold War and for its role in resurrecting the European aerospace industry. Above all, it deserves to be remembered as the breathtaking “missile with a man in it.”

For further reading, try Lockheed Aircraft Since 1913, by René Francillon.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2000 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe click here!