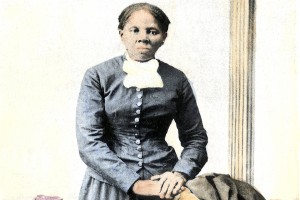

Harriet Tubman helped plan a South Carolina river raid that freed hundreds of slaves.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen the Civil War began, Harriet Tubman had already been a freedom fighter for more than a decade. As a renowned abolitionist and intrepid Underground Railroad conductor who went into slave territory to lead refugees to safety in the North and Canada, she had undertaken numerous clandestine and dangerous rescues. Tubman wasn’t afraid of assisting her escaped brothers and sisters either. In 1860 she helped liberate runaway slave Charles Nalle from a slave catcher in Troy, N.Y. Shortly after Abraham Lincoln’s call to arms in April 1861, Tubman realized that joining forces with the Federal military would increase her effectiveness in the fight against slavery, and she volunteered for duty. She enrolled first as a nurse, and then expanded her efforts to serve as a scout and spy for the Union in occupied South Carolina. Her role as an American patriot is undisputed, but her service as a war hero was challenged at the time. Over the years scholars and schoolchildren have begun to recognize her significant contributions to guaranteeing Union victory in the Civil War.

Born in 1825 to enslaved parents on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, the young Araminta, her birth name, was severely challenged. Tubman later lamented: “I grew up like a neglected weed,—ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it.” In 1849, when she heard a rumor that her owner was planning to “sell her down the river,” as siblings before her had been exiled to the Deep South, she decided to escape, to make her own journey to freedom. In doing so, she was leaving her brother, sisters and parents behind, and also deserting her husband John, a free black, who refused to leave with her. Before she undertook the journey, she assumed her mother’s name, Harriet, and her husband’s last name, Tubman.

The rechristened and self-liberated Harriet Tubman arrived in Philadelphia unharmed and launched an illustrious career as a member of the Underground Railroad. By all rights, in legend and deed, Tubman was the “Great Emancipator,” leading scores of escaping African Americans to freedom, often all the way to Canada. She built up a network of supporters and admirers, including abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and William Seward, to name but two who lauded her efforts.

When the slave power extended its tentacles into the North with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Tubman relocated to Canada along with thousands of other black refugees. Tubman risked her freedom again and again, not just by returning to the North, but also with missions into the Slave South. Her activities became even more notorious when Tubman became a staunch supporter of John Brown, who called her “General Tubman” long before Lincoln began handing out commissions.

Early in the war, Tubman informally attached herself to the military. Benjamin Butler, a Democrat, had been a member of the Massachusetts delegation to Congress and made a name for himself in the Union Army. A tough opportunist, Butler was often underestimated until his bully tactics began to pay off. Commissioned a brigadier general, Butler led his men into Maryland, where he threatened to arrest any legislator who attempted to vote for secession.

Trailing along with Butler’s all-white troops in May 1861, Tubman arrived at the camps near Fort Monroe, Virginia. The large fort and the nearby tent city of troops soon became a major magnet for escaped slaves. Tubman found herself in familiar territory.

BY MARCH 1862, the Union had conquered enough territory that Secretary of War Edwin Stanton designated Georgia, Florida and South Carolina as the Department of the South. Massachusetts Governor John Andrew, a staunch abolitionist, asked Tubman to join the contingent of his state’s volunteers heading for South Carolina, and promised his sponsorship. Andrew also obtained military passage for Tubman on USS Atlantic.

The Union troops along the coast of South Carolina were in a precarious position. They were essentially encircled, with Confederates on three sides and the ocean on the fourth. Nevertheless, Maj. Gen. David Hunter, the newly appointed Union commander of the region, had ambitious ideas about how to expand Northern control.

In November 1862, Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson arrived with the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, and Colonel James Montgomery and the 2nd South Carolina were in the area by early 1863. Escaped slaves filled both regiments, and Higginson and Montgomery both knew Tubman from before the war. In those men, both abolitionists, Tubman had gained influential friends and advocates, and they suggested that a spy network be established in the region.

Tubman had spent 10 months as a nurse ministering to the sick of those regiments, and by early 1863 she was ready for a more active role. She was given the authority to line up a roster of scouts, to infiltrate and map out the interior. Several were trusted boat pilots, like Solomon Gregory, who knew the local waterways very well and could travel on them undetected. Her closely knit band included men named Mott Blake, Peter Burns, Gabriel Cahern, George Chisholm, Isaac Hayward, Walter Plowden, Charles Simmons and Sandy Suffum, and they became an official scouting service for the Department of the South.

Tubman’s espionage operation was under the direction of Stanton, who considered her the commander of her men. Tubman passed along information directly to either Hunter or Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton. In March 1863, Saxton wrote confidently to Stanton concerning a planned assault on Jacksonville, Fla.: “I have reliable information that there are large numbers of able bodied Negroes in that vicinity who are watching for an opportunity to join us.” Based on the information procured by Tubman’s agents, Colonel Montgomery led a successful expedition to capture the town. Tubman’s crucial intelligence and Montgomery’s bravado convinced commanders that other extensive guerrilla operations were feasible.

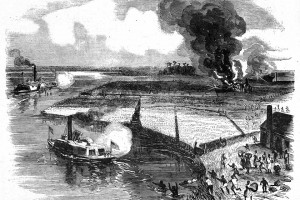

(Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863)

Their confidence led to the Combahee River Raid in June 1863—a military operation that marked a turning point in Tubman’s career. Until then, all of her attacks upon the Confederacy had been purposefully clandestine. But she did not remain anonymous with her prominent role in that military operation.

SOUTH CAROLINA’S LOWCOUNTRY rice plantations sat alongside tidal rivers that fanned inland from the Atlantic and that had some of the South’s richest land and largest slave populations. Federal commanders wanted to move up the rivers to destroy plantations and liberate slaves in order to recruit more black regiments.

The raid up the Combahee River, a twisting waterway approximately 10 miles north of Beaufort where Tubman and her comrades were stationed, commenced when the Federal gunboats Harriet A. Weed and John Adams steamed into the river shortly before midnight on the evening of June 2, 1863. Tubman accompanied 150 African-American troops from the 2nd South Carolina Infantry and their white officers aboard John Adams. The black soldiers were particularly relieved that their lives had been entrusted not only to Colonel Montgomery but also to the famed “Moses.”

Tubman had been informed of the location of Rebel torpedoes—floating mines planted below the surface of the water—in the river and served as a lookout for the Union pilots, allowing them to guide their boats around the explosives unharmed. By 3 a.m., the expedition had reached Fields Point, and Montgomery sent a squad ashore to drive off Confederate pickets, who withdrew but sent comrades to warn fellow troops at Chisholmville, 10 miles upriver.

Meanwhile, a company of the 2nd South Carolina under Captain Carver landed and deployed at Tar Bluff, two miles north of Fields Point. The two ships steamed upriver to the Nichols Plantation, where Harriet A. Weed anchored. She also guided the boats and men to designated shoreline spots where scores of fugitive slaves were hiding out. Once the “all clear” was given, the slaves scrambled onto the vessels.

“I never saw such a sight…,” Tubman described of the scene. “Sometimes the women would come with twins hanging around their necks; it appears I never saw so many twins in my life; bags on their shoulders, baskets on their heads, and young ones tagging along behind, all loaded; pigs squealing, chickens screaming, young ones squealing.”

According to one Confederate onlooker, “[Tubman] passed safely the point where the torpedoes were placed and finally reached the…ferry, which they immediately commenced cutting way, landed to all appearances a group at Mr. Middleton’s and in a few minutes his buildings were in flames.”

Robbing warehouses and torching planter homes was an added bonus for the black troops, striking hard and deep at the proud master class. The horror of this attack on the prestigious Middleton estate drove the point home. Dixie might fall at the hands of their former slaves. The Confederates reportedly stopped only one lone slave from escaping—shooting her in flight.

Hard charging to the water’s edge, the Confederate commander could catch only a glimpse of escaping gunboats, pale in the morning light. In a fury, Confederate Major William P. Emmanuel pushed his men into pursuit—and got trapped between the riverbank and Union snipers. In the heat of skirmish,

Emmanuel’s gunners were able to fire off only four rounds, booming shots that plunked harmlessly into the water. Frustrated, the Confederate commander cut his losses after one of his men was wounded and ordered his troops to pull back. More than 750 slaves would be freed in the overnight operation on the Combahee.

The Union invaders had despoiled the estates of the Heywards, the Middletons, the Lowndes, and other South Carolina dynasties. Tubman’s plan was successful. The official Confederate report concluded: “The enemy seems to have been well posted as to the character and capacity of our troops and their small chance of encountering opposition, and to have been well guided by persons thoroughly acquainted with the river and country.”

Robbing the “Cradle of Secession” was a grand theatrical gesture, a headline-grabbing strategy that won plaudits from government, military and civilian leaders throughout the North. After the Combahee River Raid, critics North and South could no longer pretend that blacks were unfit for military service, as this was a well-executed, spectacularly successful operation. Flushed with triumph, Hunter wrote jubilantly to Secretary of War Stanton on June 3, boasting that Combahee was only the beginning. He also wrote to Governor Andrew, promising that Union operations would “desolate” Confederate slaveholders “by carrying away their slaves, thus rapidly filling up the South Carolina regiments of which there are now four.” Andrew had been a champion of black soldiers, a steadfast supporter of Hunter’s campaign to put ex-slaves in uniform.

The Confederacy discovered overnight what it took the Union’s Department of the South over a year to find out—Harriet Tubman was a formidable secret weapon whose gifts should never be underestimated. Federal commanders came to depend on her, but kept her name out of official military documents. As a black and a woman she became doubly invisible. This invisibility aided her when Union commanders sent her as far south as Fernandina, Fla., to assist Union soldiers dropping like flies from fevers and fatigue.

TUBMAN’S OWN HEALTH faltered during the summer of 1864, and she returned north for a furlough. She was making her way back South in early 1865 when peace intervened, so she returned to Auburn, where she had settled her parents, and made a home. Postwar, Tubman often lived hand to mouth, doing odd jobs and domestic service to earn her living, but she also collected money for charity. She sought patrons to realize her dream of establishing a home for blacks in her hometown—for the indigent, the disabled, the veteran and the homeless.

“It seems strange that one who has done so much for her country and been in the thick of the battles with shots falling all about her, should never have had recognition from the Government in a substantial way…” chided the writers of a July 1896 article in The Chautauquan. Tubman echoed that lament: “You wouldn’t think that after I served the flag so faithfully I should come to want under its folds.”

(Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Charles L. Blockson)

In 1897 a petition requesting that Congressman Sereno E. Payne of New York “bring up the matter [of Tubman’s military pension] again and press it to a final and successful termination” was circulated and endorsed by Auburn’s most influential citizens. Payne’s new bill proposed that Congress grant Tubman a “military pension” of $25 per month—the exact amount received by surviving soldiers. A National Archives staffer who later conducted research on this claim suggested there was no extant evidence in government records to support Tubman’s claim that she had been working under the direction of the secretary of war. Some on the committee believed that Tubman’s service as a spy and scout, supported by valid documentation, justified such a pension. Others suggested that the matter of a soldier’s pension should be dropped, as she could more legitimately be pensioned as a nurse.

One member of the committee, W. Jasper Talbert of South Carolina, possibly blocked Tubman’s pension vindictively—it was a point of honor to this white Southern statesman that a black woman not be given her due.

Regardless, a compromise was finally achieved, decades after she had first applied for a pension based on her service. In 1888, Tubman had been granted a widow’s pension of $8 a month, based on the death of her second husband, USCT veteran Nelson Davis. The compromise granted an increase “on account of special circumstances.” The House authorized raising the amount to $25 (the exact amount for surviving soldiers), while the Senate amended with an increase to only $20—which was finally passed by both houses.

President William McKinley signed the pension into law in February 1899. After 30 years of struggle, Tubman’s sense of victory was tremendous. Not only would the money secure her an income and allow her to continue her philanthropic activities, her military role was finally validated. Details of Tubman’s wartime service became part of the Congressional Record, with the recognition that “in view of her personal services to the Government, Congress is amply justified in increasing that pension.”

Tubman’s heroic role in the Civil War is finally being highlighted and appreciated for what it was, part of a long life of struggling for freedom, risking personal liberty for patriotic sacrifice.

Civil War Times advisory board member Catherine Clinton holds the Denman Chair in American History at the University of Texas in San Antonio. She is the author of Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom, among many other volumes on the Civil War.