As Nazi Germany prepared to invade France in 1939, a few months after conquering Poland, American expatriate Charles Sweeny left his wife and children in Paris and sailed to Canada. He wasn’t, however, running from a fight. Sweeny, an outspoken foe of German aggression and critic of American apathy, aimed to plunge headfirst into the coming war.

Sweeny’s audacious plan was to recruit 150 American pilots and form a new Lafayette Escadrille—the legendary volunteer flying unit in World War I—to fight for France. But with the outbreak of war in Europe, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had issued a proclamation forbidding Americans from joining the military of a warring nation or from hiring others to do so, in keeping with U.S. neutrality laws.

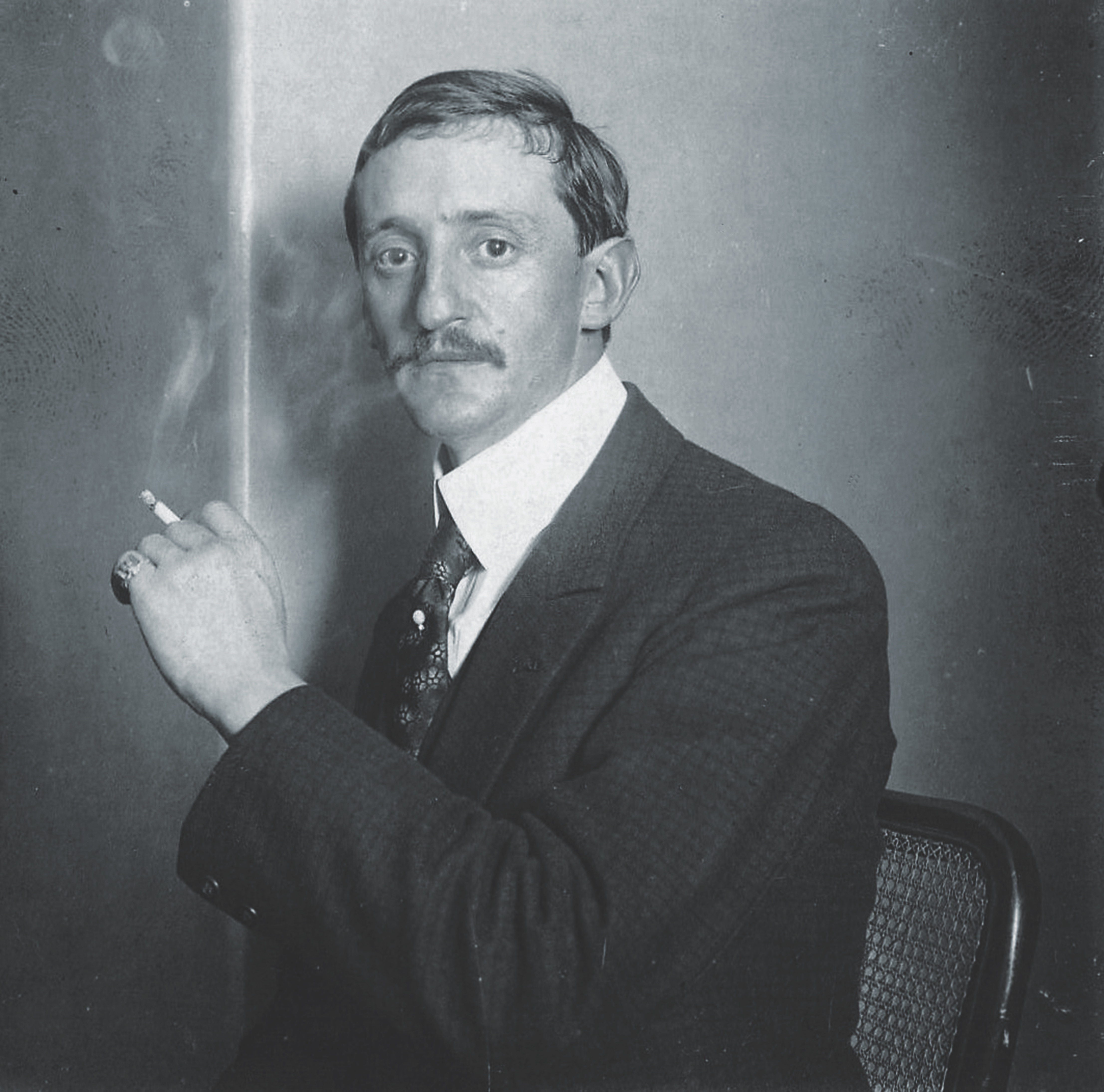

Never one to follow rules, Sweeny, ignoring his potential legal jeopardy, proceeded to issue a public call for volunteer fliers, whom he intended to spirit out of the United States through Canada. Had he been an ordinary citizen, his appeal might have gone unnoticed. But Sweeny was America’s most celebrated soldier of fortune, and his bold appeal for volunteers immediately attracted international attention. Sweeny’s impudence outraged J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who mobilized his G-men to stop Sweeny cold.

Sweeny’s first job was to organize a network of people to help him find recruits, provide them with instructions and money, and help them get out of the United States, into Canada, and on to Europe. Both the FBI and Canadian authorities were watching Sweeny, so he had to employ stealth and deception to move and communicate. It was a classic game of cat and mouse, but the cats in this case were no match for the mouse’s decades of experience as a soldier, journalist, and spy.

By January 3, 1940, Sweeny had slipped away from the government agents watching him, crossed the U.S.-Canada border, and quietly taken a room at a hotel in Santa Monica, California, to begin recruiting. That location put him near Mines Field (now Los Angeles International Airport) and Clover Field (now Santa Monica Municipal Airport), the home of Douglas Aircraft Company.

Among Sweeny’s first potential recruits were student pilots Clyde Hamilton Hodges, 19, of Los Angeles and Kendall Winton Everson, 18, of Inglewood. According to Everson’s unpublished autobiography, his friend Hodges saw Sweeny’s August 1939 announcement and wrote to Sweeny in Paris. Sweeny wrote back in October to say he would be in contact soon. In January 1940, Sweeny invited Hodges and any of his pilot friends who were interested to a midday meeting in what Everson later described as “a dark, back corner” of the hotel’s bar. Hodges and Everson brought along two other student pilots, William Scott Raney, 21, and Walter Edwin Palmer Jr., 20, both of Los Angeles. The foursome’s flying experience ranged from 30 hours for Everson to several hundred hours for Palmer.

“We were all impressed by his demeanor and especially impressed by the small civilian replica of the Croix de Guerre, which he wore on his left coat lapel,” Everson would later recall. Sweeny told the young men that he was recruiting pilots to form a new Lafayette Escadrille. He told them they would be trained at a French air base in Morocco and then sent to Finland to fly with the Finnish air force against the Russians, who had invaded Finland. After gaining some combat experience, they would return to France to fly against the German Luftwaffe. All four men, Everson said, were eager to sign up.

Sweeny told the men they would leave for Detroit by train from Union Station in Los Angeles. One of Sweeny’s men would meet them in Detroit and get them across the border into Canada. They would then proceed to the Wellington Hotel in Toronto, where they could enlist and then travel by ship to Le Havre, France. “Sweeny spoke in low tones so as not to be overheard by anyone passing or sitting nearby,” Everson later recalled. “He swore us to secrecy, admonishing us to speak to no one about this meeting or our plans.” They knew that what they were planning to do was illegal. “Mr. Sweeny was well aware of this, lending a decided ‘cloak and dagger’ air to everything he did and said, and by extension to everything we did after becoming associated with him. All this seemed to add to the excitement and appeal of the whole adventure.”

A couple of weeks later, the four men again met with Sweeny at the Santa Monica hotel. This time they received train tickets to Detroit, $20 to cover expenses, and detailed instructions. They were told other recruits would board the train as it traveled through Southern California but that they should avoid any contact with them for fear of tipping off others. They were to board the train at 9 p.m. on Friday, February 23, 1940.

The young men had agreed among themselves to mail letters from the train station telling their parents where they had gone. The day before they were to leave, however, Everson decided to share his plans with his father. But instead of telling his son he couldn’t go, Everson’s father offered him an alternative: If his son would forgo Sweeny’s offer, he would help him join the U.S. Army Air Corps. Everson accepted the offer.

Everson informed the other young men of his decision and agreed to drive them to the train station. After seeing them off, he dropped their letters in a mailbox. But none of them had figured on how long it would take the train to reach Detroit. The letters were delivered on Monday while the train was crossing Kansas. Hodges’s parents immediately called the FBI. The next day, a Los Angeles Examiner story, “Allies Lure L.A. Boys Into War Air Service,” was front-page news across the nation. Palmer’s parents called relatives in Illinois and “five of Walt’s uncles met the train in Chicago and dissuaded him from going any further,” said Everson. FBI agents then met the train in Detroit and kept Hodges and Raney from crossing into Canada.

While Everson later became a decorated Marine Corps aviator in the South Pacific, the lives of the other three men were cut tragically short. All three died in stateside air crashes unrelated to Sweeny within 18 months of boarding the train, before America had even entered the war.

THE NEWSPAPER STORIES ABOUT THE YOUNG PILOTS ON THE TRAIN IDENTIFIED SWEENEY AS THEIR RECRUITER. An Associated Press story on February 28 quoted Palmer as saying that “at least 20 youths” had been recruited on the West Coast for war air service. The same day, the Los Angeles Examiner reported that while Sweeny was in Santa Monica he had sent telegrams to people in several cities in the United States and Canada. The article concluded that Sweeny was “only one of several individuals involved in the asserted foreign recruiting operations.” It noted that one telegram, sent to a Dudley Hill in New York City on February 19, read: “Wire if you have confirmed deposit of money. If deposited, proceed as outlined. First shipment leaves here Friday. Desirable you should be on ground prepared to receive it. Shipment about the size of yours, which I suppose is already sent. Keep me informed.”

The proprietor of the Santa Monica hotel told the Examiner that Sweeny had been a guest January 3–6 and again February 12–23, and that on February 22 Sweeny had made many telephone calls to numbers in Los Angeles. He recalled that a lot of young men “flocked to the hotel” that night and the next morning, waving train tickets but refusing to say why they were there.

Clearly, Sweeny and his helpers had managed to start several “shipments” on their “underground railroad.” Sweeny later credited two men in Southern California with coming forward at the outset and saving the plan. One was Joseph Everett Weddle of Los Angeles. The other was Edwin C. “Ted” Parsons of Hollywood, who, like Dudley Hill, had been a member of the original Lafayette Escadrille.

A February 26, 1940, memo from the FBI’s Los Angeles office reported that two men “formerly employed at the Douglas Aircraft Company, Santa Monica…were en route from Los Angeles, California, to Toronto, Canada, for the purpose of enlisting as cadets in the French Aviation Service, and that a Colonel Sweeny connected with the French Government purchased their railroad tickets.”

None of the four young men recruited with Everson worked for Douglas Aircraft, so this was a different set of men. Among a group of recruits who had worked at Douglas Aircraft and boarded trains for Canada around that time was 19-year-old Chesley Gordon Peterson of Santaquin, Utah. He had flunked out of pilot training at Randolph Field near San Antonio, Texas, and taken a job with Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica. Peterson later said that he and some friends from a flying club went to meet Sweeny when they learned that he was at a local hotel. Sweeny outlined the scheme to get them to Europe and said that one of his men, Weddle, would let them know when they were to leave. The call from Weddle came in February 1940. The recruits boarded the train and after several days arrived at the station in Windsor, Ontario, across the river from Detroit. Two government agents met them there and sent them back to California.

When the men arrived back in Los Angeles, Weddle told them that Sweeny had come up with a new plan. This time they would travel as Red Cross workers for an American Volunteer Ambulance Corps unit in France. Once there, Weddle explained, they would join the French Foreign Legion as fliers. When this plan later fell apart, the members of the group made their own plan. They took a train to Chicago, split up, took different trains into Canada, and reassembled in Ottawa.

The plan changed again on May 10 when Germany invaded France. Now, instead of heading to France, seven of Sweeny’s recruits sailed to England. In addition to Peterson, they were Paul Anderson, Edwin Orbison, and Dean Satterlee, all from Sacramento; Richard Moore of Fort Worth; Byron Kennerly from Pasadena; and James McGinnis from Hollywood. Ironically, Anderson was the son of the head of the FBI’s San Francisco office.

On May 10 two more recruits left Los Angeles for Canada. One was Eugene “Red” Tobin, 23, of Los Angeles. He had cut classes in high school to take flying lessons and then scraped together enough money to buy his own plane. That led to a job flying actors and executives around California for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. The other was Andrew Mamedoff, 27, of Thompson, Connecticut. He had flown in air shows and operated a small air charter service. When their train reached the Canadian border, FBI agents questioned Tobin and Mamedoff but took them on their word that they were visiting a cousin to go fishing.

When Tobin and Mamedoff arrived in Montreal, they went to the Queen’s Hotel and asked for a letter that was supposed to be waiting for them with cash and train tickets to their next stop. It wasn’t there. They asked if any other American guests had asked for a letter and were pointed to a man sitting in the lobby reading an aviation magazine. He was Vernon Charles “Shorty” Keough, 26, a 4-foot-10 Brooklyn-born barnstormer and parachute jumper. The three men decided to have a drink in the hotel bar, and while they were there the letters arrived. Inside were train tickets that got them to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where a man met them and gave them each a pink card stating they were people of “indeterminate nationality” and were to be given free passage to France to join the French Air Service. They sailed the next day and arrived in France on May 31.

Meanwhile, FBI agents were on Sweeny’s trail and nearly collared him in Texas. As the G-men boarded the train he was on, Sweeny abruptly changed trains, leaving his luggage behind.

Sweeny eluded the FBI and in the spring of 1940 returned to France. The first of his recruits had reached Canada on April 13 and been promptly packed off to Europe, and by May 10 a total of 32 men had begun the journey.

Unfortunately, Sweeny’s recruits arrived too late to fight for France. On May 10—the day Tobin, Mamedoff, and Keough left for France—Germany invaded the neutral nations of Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. By May 26 French and British forces were bottled up at Dunkirk. An epic seaborne rescue plucked 338,000 troops off the beaches by June 4, and France surrendered on June 22.

Britain now stood alone and practically defenseless as it awaited a cross-Channel German invasion. Sweeny knew that Britain could not fight for long without help, and he was determined to do whatever he could to fight fascism.

IN THE CHAOS FOLLOWING THE COLLAPSE OF FRANCE, Sweeny left his wife and three children behind in Paris to try to spirit his recruits out of France. (Two of his adult children later made their way to neutral Portugal and then to United States, while his wife and youngest child, who had serious birth defects, remained in France.)

Of the 32 Sweeny recruits who reached France, four were killed and nine were captured by the Germans. Six of them made their way to England, including Mamedoff, Tobin, and Keough. The others managed to make their way out just barely ahead of the invaders. Some returned to the United States.

Back in America, FBI agents were still trying to break up Sweeny’s recruiting network. In addition to the G-men in Los Angeles, agents from nearly a dozen FBI offices from coast to coast were drawn into the hunt.

Meanwhile, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover badgered the State Department to help him reel in Sweeny. Hoover and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle Jr. exchanged at least nine memos about Sweeny, delivered by special messenger, from February 5 to April 19, 1940.

Given the tenor and tempo of Hoover’s memos, it is somewhat surprising that he met with continued resistance from Berle. Even though Hoover had a well-earned reputation as a skilled bureaucratic infighter, Berle was able to parry each of Hoover’s thrusts in this intramural fencing match. The State Department’s slow-walking approach surely infuriated the FBI director.

Meanwhile, in England, Sweeny’s namesake nephew, financier and socialite Charles Sweeny, used his connections in the British government to secure permission to form a flying squadron of American volunteers. On July 2, 1940, the elder Sweeny’s recruits became the nucleus of three Eagle Squadrons in the Royal Air Force, and he was appointed honorary group captain.

Keough, Mamedoff, and Tobin were among 30 American pilots listed as the initial “Eagles” with No. 71 Squadron, RAF. All three were later killed in action. The list also included Anderson, Kennerly, McGinnis, Moore, Orbison, Peterson, and Satterlee. Peterson later became the youngest squadron leader in the RAF and the youngest colonel in the U.S. Air Force at age 23.

The young men who answered Sweeny’s call for volunteers were, like Sweeny, adventurers, patriots, and true believers in righteous causes.

AS HEIR TO ONE OF AMERICA’S GREAT FORTUNES OF THE GILDED AGE, Sweeny could have been a gentleman of leisure and privilege. Instead, he risked his life and liberty, and spent much of his personal wealth, to fight for causes he believed in, to battle fascism in Europe, and to oppose tyranny around the globe.

After being kicked out of West Point—twice—Sweeny joined revolts in Latin America, enlisted in the French Foreign Legion to fight the German kaiser, became the first American to earn France’s highest medal for valor in World War I, and commanded a U.S. Army battalion in that war. He also led troops in aerial and ground combat in foreign armies in Poland, Morocco, and Spain between the world wars before recruiting pilots to fight the Nazis ahead of America’s entry into World War II. For a time, it seemed that wherever there was a war, there was Sweeny.

Just as Sweeny couldn’t seem to get enough of combat, journalists couldn’t seem to get enough of Sweeny. Newspaper accounts of his adventures included sensational claims that he had fired a cannon into the roof of the commandant’s house as a prank while a West Point cadet, talked his way out of a firing squad execution in Venezuela, been offered a harem as a reward for his services to the sultan of Morocco in the Rif War, and narrowly escaped assassination by Nazi agents on a Paris street.

He also captured the imagination and admiration of Ernest Hemingway, who became a lifelong friend after they met during the Greco-Turkish War of 1922, and was one of the famous author’s real-life role models for his fictional manly heroes. Each saw in the other some of the character traits and talents they envied or wished to emulate.

SWEENY WAS BORN ON JANUARY 26, 1882, IN SAN FRANCISCO, to Charles and Emeline Sweeny. Through luck, skill, and raw nerve, Sweeny’s father, the son of poor Irish immigrants, amassed a huge fortune from silver mining in Idaho.

Young Sweeny entered the U.S. Military Academy in 1900 as a member of the class of 1904. A mediocre student and a discipline problem, he was kicked out in 1901, readmitted in 1902 through the political influence of his father, and kicked out again in 1903. There was a cannon incident during a cadet “mutiny” at West Point in 1901, but there is no evidence Sweeny was involved. Whether he invented his role in the incident or some journalist conflated the facts, Sweeny never bothered to refute this or other myths that attached themselves to him. Later news stories attributed his final expulsion to the cannon incident, but the actual cause was more prosaic: He flunked philosophy.

After West Point, Sweeny’s father sent him to Mexico to scout mining sites. Instead Sweeny joined a revolt against Mexico’s president, Porfirio Díaz, and saw combat for the first time. He loved it. The revolt fizzled, but it lit the fuse to the powder keg of economic and political grievances that exploded four years later in the Mexican Revolution of 1910.

After Mexico, Sweeny joined an invasion of Venezuela as part of “the Asphalt Wars,” an armed conflict over foreign control of a giant lake of asphalt much sought after to pave roads in the United States. He was captured and escaped a firing squad only through an audacious bluff. He falsely claimed to be an American newspaper reporter accompanying the rebel force rather than one of its officers. He persuaded the dictator that executing him would trigger an invasion by U.S. Marines aboard the American warships patrolling off the coast, and the dictator let him go. He next joined a revolt against the dictator of Nicaragua, and once again he narrowly escaped with his life.

In 1910 Sweeny moved to France, married, and started a family. When World War I erupted, he immediately recruited and led a contingent of 43 American volunteers into the French Foreign Legion. Over the next three years he became the first American to be appointed an officer in the legion and the first American to receive the Legion of Honor in that war. He also was awarded the Croix de Guerre seven times. Sweeny received the Legion of Honor during the 1915 Champagne Offensive for singlehandedly storming a machine-gun position, killing its six-man crew, and saving the life of his commander. He suffered a near-fatal chest wound in this action at Navarin Farm, a key German strongpoint. His recovery took many months. When he returned to action it was as the commander of one of the first tank squadrons in the war.

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, Sweeny transferred to the U.S. Army and led a battalion of the 318th Infantry Regiment of the 80th Division in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. He was twice cited in dispatches, more than any other officer in his regiment, and was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross. He ended the war as a lieutenant colonel.

In the 1920s and 1930s Sweeny exercised his deep hatred of totalitarian governments—especially the fascist regimes of Adolf Hitler and Francisco Franco. He was a brigadier general in the Polish-Soviet War, commander of a flying squadron in Morocco’s Rif War between colonial powers and native tribes, a military adviser to the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, and a French intelligence agent in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought America into the war, Sweeny returned home and hatched a plan with “Wild Bill” Donovan of the Office of Strategic Services to create a guerrilla force of local tribesmen to fight the Nazis in North Africa. President Roosevelt personally approved the plan, but the State Department shot it down. A similar plan for Yugoslavia met the same fate.

Resigned to being an armchair combatant, Sweeny wrote a book outlining how he thought the war could be won. In it he wrongly predicted that any D-Day invasion of France would fail and instead advocated sending Allied troops through Siberia to bolster the Russian front. He also wrote pamphlets that criticized Roosevelt for meddling in war plans, blamed him for Pearl Harbor, and defended Marshal Philippe Pétain, the Vichy leader tried for treason.

After the war, Sweeny, estranged from his wife, settled in Salt Lake City as the permanent houseguest of an old flame. He died there at age 81 on February 28, 1963. Despite having seen more wars than most old soldiers, Sweeny outlived many of his famous contemporaries but not his own fame. His death was front-page news in newspapers all across America. MHQ

—Charley Roberts is a California journalist and military historian and Charles P. Hess is a Utah business executive and historian. They are the authors of Charles Sweeny, the Man Who Inspired Hemingway (McFarland & Company, 2017), from which this article is adapted.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Hunted Hero