In Western frontier history, you might call it the “Great Escape.” After all, Davy Crockett didn’t escape the Alamo, George Custer didn’t escape the Little Bighorn, and Nez Perce Chief Joseph didn’t escape the U.S. Army. But Billy the Kid did escape the Lincoln County Courthouse! New Mexico Territory’s Lincoln County War boosted the Kid into the national spotlight in the late 1870s, but it wasn’t until his dramatic escape from the courthouse in April 1881 that he secured his place near the top of the all-time badmen heap. Getting shot down by Pat Garrett at Fort Sumner less than three months later certainly cemented Billy’s legend—which might have suffered had he not died so young — but the Kid didn’t exactly go out in a blaze of glory. And Garrett never would have gotten his chance at the gutsy, if not heroic, gunman had it not been for Billy’s great—well, not so great for two Lincoln County lawmen—escape.

Actually, Garrett had a role—albeit in absentia—in Billy’s April 28, 1881, breakout. Running on a law-and-order platform, Garrett had been elected sheriff of Lincoln County in November 1880 and had captured Billy the Kid at Stinking Springs the next month. Then, in Mesilla on April 13, 1881, Billy had been convicted of the murder of Sheriff William Brady, one of the casualties of the Lincoln County War, and sentenced to hang. The execution was to be carried out in Lincoln on Friday, May 13, and seven guards had transported the prisoner there in the middle of April. So on April 28, the Kid was very much Garrett’s responsibility. And the sheriff did not take his responsibility lightly. Garrett did not keep Billy in Lincoln’s old cellar jail, which he knew would never hold a cunning prisoner whose very life depended on getting out. Instead, Garrett kept the Kid shackled hand and foot and guarded around the clock in the room behind his own office at the county courthouse, which had been the old Murphy-Dolan store (commonly referred to as “the House) during the Lincoln County War.

That bitter feud was fresh in everybody’s mind. Lawrence Murphy had aligned himself with James J. Dolan for economic control of the region, and when an Englishman named John Tunstall came along and proved himself to be competition, trouble followed. Tunstall’s murder on February 18, 1878, and Sheriff Brady’s subsequent refusal to arrest the men responsible led to ‘war.’ Teenager Billy the Kid (born Henry McCarty in 1859, probably in New York) had been employed by Tunstall. After Tunstall’s death, Billy and several other so-called Regulators killed three members of the Dolan faction and then assassinated Brady and Deputy George Hindman. Additional killings followed, but it was the killing of Brady that now had the Kid cooling his heels in the makeshift ‘death row’ at the Lincoln County Courthouse.

On Thursday, April 28, 1881, Sheriff Garrett was collecting taxes in White Oaks — a sheriff still had to carry out his duties even when he had a celebrated outlaw in his custody. Garrett had assigned deputies Bob Olinger and James W. Bell to guard Billy. The Kid’s room was on the second story, across the hall from the room where Garrett kept his more ordinary prisoners. Ironically, the room where Billy the Kid was awaiting his execution day had once been the bedroom of his old enemy, Lawrence Murphy.

If Billy the Kid didn’t have reason enough to free himself, Olinger gave him another reason by continually harassing him. A woman who had seen Olinger guarding Billy was interviewed more than 50 years after the fact (see They ‘Knew’ Billy the Kid: Interviews with Old-time New Mexicans, edited by Robert F. Kadlec). She said of the guard: ‘He was a big burly fellow, and every one that I ever heard speak of him said he was mean and overbearing, and I know that he tantalized Billy while guarding him, for he invited me to the hanging just a few days before he was killed. Even after he was killed I never heard any one say a single nice thing about him.’ Garrett himself said that Olinger and Billy the Kid had a ‘reciprocal hatred.’ Olinger and the Kid had supported opposing factions during the Lincoln County War, and Olinger had killed Billy’s friend John Jones in August 1879.

Billy’s guards supposedly drew a deadline in chalk across the middle of the room — should Billy ever step over it, he would be shot. If true, it was no doubt Olinger’s idea. The other guard, Bell, apparently treated the prize prisoner well; Garrett said that the Kid ‘appeared to have taken a liking’ to Bell. Garrett, by his own account, also treated Billy fairly. In his The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, Garrett said that Billy acknowledged that the sheriff had only done his duty ‘without malice, and had treated him with marked leniency and kindness.’ But based on how the Kid treated Bell on April 28, it’s hard to imagine that he would have shown any ‘leniency’ toward Garrett had the sheriff been in Lincoln instead of out collecting taxes that fateful day.

Between 5 and 6 p.m. on the 28th, Olinger took the five other prisoners across the street to Sam Wortley’s hotel for dinner. Billy remained in his room, with Bell keeping watch. It is commonly accepted that the Kid asked Bell to take him to the outhouse in back of the courthouse. Bell obliged. The men went outside, Billy still in his leg-irons and chains and with handcuffs still on. Once back in the building, Billy the Kid made his move.

Godfrey Gauss, who had cooked for Tunstall and was living in a house behind the courthouse with Sam Wortley, happened to be outside at the time. He heard a shot, and when he looked up, he saw Bell burst out of the courthouse’s back door. ‘He ran right into my arms, expired the same moment, and I laid him down dead,’ Gauss later said. Bell had been shot through the body.

Olinger, still dining at the hotel, heard the shot and came outside with the five prisoners. Gauss called out to him, asking him to hurry back across the street. Olinger did so, without the prisoners. As he entered the courthouse yard, Olinger heard his name called by somebody else — somebody from above. When Olinger looked up, he saw his own double-barreled shotgun pointing down at him from an upstairs window on the courthouse’s east side. Somehow, Billy had been able to get the shotgun out of Garrett’s office. ‘I stuck the gun through the window and said, ‘Look up, old boy, and see what you get,” recalled Billy. ‘ Bob looked up, and I let him have both barrels right in the face and breast.’ Olinger died instantly.

Billy then spotted Gauss behind the courthouse, but Billy wasn’t after any more blood. Both men who had been guarding him were dead, and Gauss was a friend. Billy asked him to throw up a pickax, and Gauss did not hesitate in coming to the aid of a friend in need. The Kid then requested a saddled horse as he worked the pick on the chain connecting his shackles. Gauss brought the horse. By then, the Kid had quite an audience — the five other prisoners and many of Lincoln’s fine citizens. Nobody tried to interfere with Billy’s plans. No doubt some of them had nothing against Billy. According to some accounts, the Kid shook hands with a lot of folks before riding out of town. Even more of them may have been paralyzed by fear. Garrett thought so. In any case, Billy found no reason to rush. One of the witnesses said that by the time Billy finally rode off, Bell and Olinger had been dead for more than an hour.

One of the big questions afterward was how Billy the Kid had managed to get a revolver and shoot Bell. Sheriff Garrett, who learned of the escape the next day (April 29), certainly wanted to know. After returning from White Oaks, he examined the building and interviewed Gauss and other witnesses. Garrett said he found that the room serving as the armory had been broken into; he also discovered a bullet in the wall of the stairwell. The bullet had apparently ricocheted off the right-hand wall, passed through Bell’s body and lodged in the opposite wall. From that evidence, he surmised that Billy had obtained the revolver from the armory.

But how had Billy been able to get away from Bell and reach the armory? Garrett’s explanation was that Billy — with leg shackles and all — had somehow hurried ahead of Bell on the way back from the outhouse, gone inside the courthouse well ahead of the deputy, rushed up the stairs and broken into the armory. Breaking into the armory would have been easy, Garrett said, because even when the door was locked, it could be opened with a push. One of the men watching from the street said that when Billy appeared on the upper porch in front of the building, he ‘had at his command eight revolvers and six guns [rifles]’ — weapons undoubtedly filched from the armory. Of course, Billy would have only grabbed one loaded gun at first, which was all he needed to dispatch Bell as the deputy came up the stairs. But more questions arise. Was there time for Billy to do all that? Why did Bell dawdle so? If the Kid had managed to get so far ahead, wouldn’t Bell have drawn his gun and shot him?

Another possibility is that Billy found the revolver in the outhouse. Maurice Fulton, a tireless researcher of New Mexican history during the 1920s and 1930s, liked the version in which Sam Corbet, who had been Tunstall’s clerk, aided Billy. According to that version, Corbet had visited Billy every day and, despite the watchful eyes of Olinger and Bell, had managed to slip him a note on which one word was written — ‘Privy.’ Not much of a clue, but Billy was a sharp youth, and he somehow got the message — there would be a revolver waiting for him in the outhouse. The revolver had been wrapped in a newspaper and planted in the outhouse by another friend, José Aguayo. The outhouse was open to the public, so somebody else could have found the weapon. But nobody else did. On his trip to the outhouse in the early evening of the 28th, Billy had retrieved the gun and hid it in his clothes. Once back inside the courthouse, the Kid had then pulled the revolver from its hiding place and shot the unsuspecting Bell.

Another version involves Billy’s handcuffs and is offered by Robert M. Utley in Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life. Utley contends that ‘Bell carelessly lagged behind’ when he and Billy were returning from the outhouse, and that after Billy reached the top of the stairs, he slipped one hand out of his cuffs. When Bell made it up the stairs, Billy’swung the loose cuff in vicious blows that laid open two gashes on the guard’s scalp’ and knocked him down. Then, according to Utley’s version, Billy wrestled Bell for the deputy’s gun. Billy got the gun and fired it as Bell fled down the stairs. The bullet hit the mark, and Bell staggered outside before he died in Godfrey Gauss’ arms. Billy, meanwhile, took Olinger’s shotgun from Garrett’s office and went to the window in the northeast corner room to deal with other threats. Soon, he eliminated the only immediate threat — Olinger.

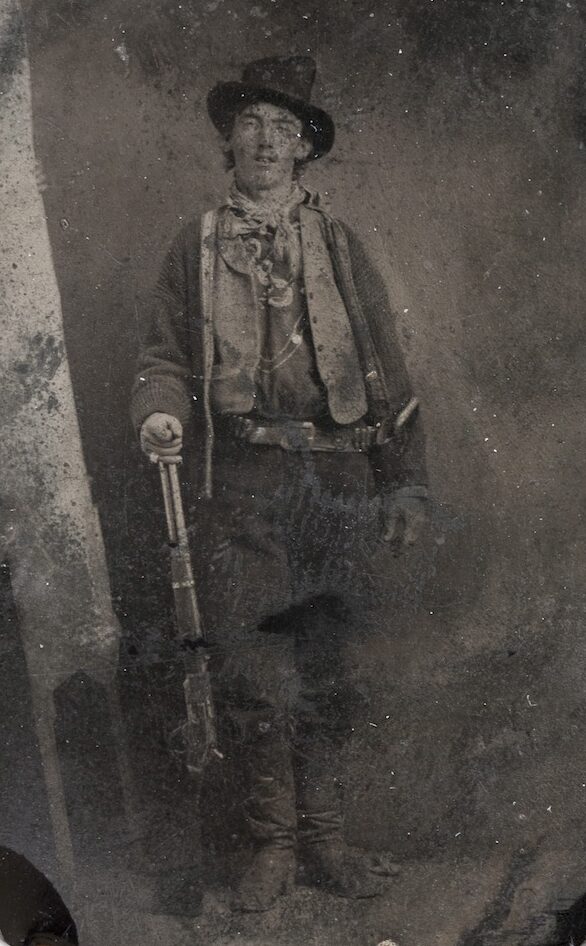

Most likely the Kid would have been able to free a hand from the handcuffs. Pat Garrett said that Billy had large wrists that tapered into slender hands. And other people who knew the Kid mentioned his small, almost feminine hands. While under house arrest at the Lincoln home of Juan Patron in March 1878, Billy supposedly had greeted each visitor by slipping his hand out of the cuffs to shake hands. Garrett also learned, presumably from eyewitnesses, that Billy had removed his handcuffs in the same manner after killing Bell. According to Garrett, Billy threw the cuffs at Bell’s body and said, ‘Here, damn you, take these, too.’

Early in May 1881, the territorial newspapers began to receive letters regarding Billy’s escape, and the handcuffs were usually mentioned. The Santa Fe Daily New Mexican printed one such letter on May 3. ‘Quick as lightning he [Billy] jumped and struck Bell with his handcuffs, fracturing his skull,’ said the anonymous correspondent. ‘He immediately snatched Bell’s revolver and shot him.’

Another letter reported, ‘Bell lay dead in the back yard with two gashes on his head, apparently cut by a blow from the handcuffs.’ Still another correspondent wrote, ‘[Billy] said he grabbed Bell’s revolver and told him to hold up his hands and surrender; that Bell decided to run and he had to kill him.’ The Kid himself may also have mentioned the handcuffs. Not long after escaping Lincoln, Billy spent one night at friend John P. Meadows’ cabin on the Penasco River. According to Meadows, who was interviewed by Maurice Fulton in 1931, Billy told him that he had hit Bell with his handcuffs and then had shot the deputy with his own gun.

All the details of Billy’s great escape will never be known, of course. Bell didn’t live long enough to say anything to anyone, not even to old Godfrey Gauss. Officials could never question the Kid about it because he remained a fugitive until Garrett killed him on the night of July 13, 1881, at Fort Sumner. But every detail was not needed to stir up the newspapers and the public. If Billy had left the town of Lincoln stunned, he also left the territory in shock. The Daily New Mexican of May 3, 1881, called the April 28 killings and escape ‘as bold a deed as those versed in the annals of crime can recall. It surpasses anything of which the Kid has been guilty so far that his past offenses lose much of heinousness in comparison with it, and it effectually settles the question whether the Kid is a cowardly cutthroat or a thoroughly reckless and fearless man.’ Billy, according to the newspaper, had exhibited ‘a coolness and steadiness of nerve in executing his plan of escape.’

‘Newspapers across the country went wild,’ writes Joel Jacobsen in his book Such Men as Billy the Kid. ‘The impossible had happened: Billy the Kid, the outlaw king of the frontier, had lived up to his reputation.’ Utley concurs. In his Billy the Kid, Utley says that the Kid was famous before his Lincoln escape thanks to the territorial press, but that despite his deeds during the Lincoln County War, he had not done enough in his 21 years to justify his fame. ‘The sensational bolt from Lincoln, however, transformed him into the territory’s foremost outlaw in fact as well as in name,’ Utley suggests.

At the courthouse today, two plaques mark the spots where Bell and Olinger fell. A large hole in the wall at the bottom of the stairs may have been made by one of the Kid’s bullets. Billy the Kid probably took some pleasure in killing ‘mean’ Bob Olinger, and he might have regretted killing the much more pleasant James Bell — well, maybe not too much regret. Garrett had repeatedly cautioned his guards about the ‘daring and unscrupulous’ Billy because he ‘knew the desperate character’ of a man who ‘would sacrifice the lives of a hundred men who stood between him and liberty, when the gallows stared him in the face, with as little compunction as he would kill a coyote.’

This article was written by Barbara Tucker Peterson and Louis Hart and originally appeared in the August 1998 issue of Wild West magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!