[dropcap]B[/dropcap]eneath the immense crystal chandelier of the Greenbrier’s Cameo Ballroom, Germans and Japanese were about to fight. The scene was an April 1942 “get-to-know-you” dance for German and Japanese diplomats, staff, and families caught behind enemy lines since Pearl Harbor and temporarily detained at the White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, resort. But when a Japanese man invited a German woman onto the dance floor, the Germans took offense. Axis allies squared off until supervising FBI agents intervened.

Until a few days before the April dance, the Germans had shared quarters at the Greenbrier with a group of Italians—all since December 22, 1941, awaiting exchange for Americans similarly detained overseas. Though under watchful FBI eyes, the two groups were at each other’s throats. When Germans “Sieg Heiled,” Italians ignored them, and greeted German affronts with challenges to duel. On April 2, 1942, realizing the Greenbrier’s social dynamics needed reshuffling, authorities sent the 237 Italians to the Grove Park Inn—in Asheville, North Carolina—and replaced them with the 330 Japanese previously housed at the Homestead, an equally posh facility in Hot Springs, Virginia.

Unfortunately, German-Japanese cohabitation proved even worse than German-Italian. The ballroom ruckus was just one example of the racial animus and mockery the Germans displayed. On April 18, when news of the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo reached the Greenbrier, Germans greeted Japanese venturing into the dining room with long shrill whistles—like falling bombs—culminating in loud slaps on the tables.

One of the Americans keeping the sides apart was 33-year-old Roy L. Morgan, a husky, balding West Virginia native. Morgan’s easygoing manner made him ideal to head security for the Japanese detainees and, in true G-man fashion, he cultivated low-level informants among them.

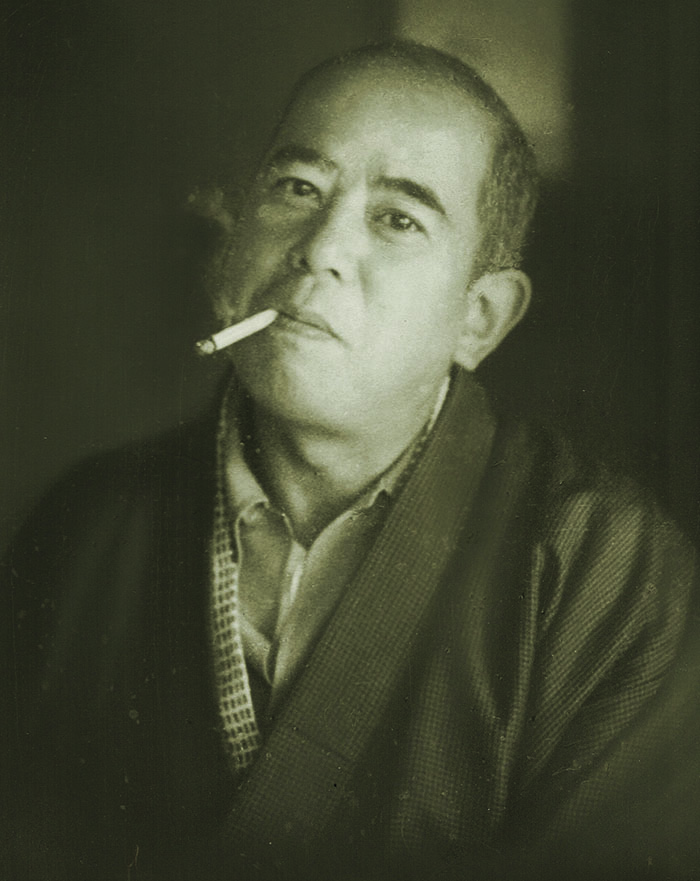

That effort evolved into a close relationship with Japan’s Washington embassy press attaché, Hidenari Terasaki, 42. Dapper and ingratiating, Terasaki became a frequent source of information, which Morgan transmitted, from the Homestead and later the Greenbrier, to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Terasaki was angered by the “authoritative and overbearing” Germans whose fatherland “is out to get all it can of Japan.” But he was also intent on setting the record straight on just how and why Japan had stumbled into war with the United States.

POSTED TO JAPAN’S WASHINGTON, DC, embassy in March 1941 as war clouds gathered, Hidenari Terasaki possessed unique qualifications—along with a potential liability. Fluent in English, he was well versed in American life and customs from studies at Brown University. But his affinity for the United States had taken a risky turn. In 1930, during his first DC posting, he met Tennessee native Gwendolen Harold at an embassy function. The couple courted and planned to marry, but their “East-meets-West” union (she called him “Terry”) faced resistance. While Gwen’s mother reconciled to the marriage, her father and many Tennessee relatives never did. For Terry, the marriage required special family and government dispensations. With his parents deceased, Terry, by established custom, sought and obtained permission to marry from his elder brother Taro, a highly placed foreign ministry official.

In overcoming official hurdles to marrying a foreigner, Terry could point to the example of Saburo Kurusu, a ranking diplomat who had married an American. Terry also possessed an influential patron: Mamoru Shigemitsu, then Japan’s ambassador to China. Still, while Japan’s foreign ministry reluctantly assented to the marriage, Gwen thereafter became known in Japanese diplomatic circles as “Terasaki’s folly.”

Amity with America began to sour around the time Japan transferred Terry and Gwen to Tokyo in 1932. After aggressively subjugating Manchuria that year, the belligerent empire embarked on a full-blown Sino-Japanese war. During the De- cember 1937 siege of Nanking, Japanese aircraft sank American gunboat Panay, killing or wounding scores of Americans. Then, in September 1940, Japan joined Germany and Italy in the Tripartite Pact, a mutual defense alliance supporting Japan’s hegemony in Asia.

In such fraught times, suspicions preceded the couple’s March 1941 return to the United States. In February, the FBI received a letter from Gwen’s first cousin, U.S. Army Air Corps Lieutenant Richard C. Hughes. Angered at Gwen’s “disgraceful marriage,” Hughes had “reason to suspect” her loyalty. Gwen’s “Jap husband” might order her to “gain access to information or place[s]which would be inaccessible to him.”

Of more consequence, however, were the conclusions high-level American intelligence officials had reached about Terry. The U.S. military was deciphering Japanese diplomatic dispatches that suggested Terry’s duties might include espionage. One December 1940 decrypt revealed that Terry’s actual job would be “widening the [Japanese] intelligence net…even if there should be a severance of…relations.” The State Department and FBI pegged Terry as Japan’s American “spymaster.”

THERE WAS SOME TRUTH IN THIS, but the circumstances were more complicated. There indeed were full-fledged Japanese spies using diplomatic cover. The same month Terry reached Washington, three U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence operatives burgled Japan’s Los Angeles consulate and photographed documents exposing Japan’s entire West Coast spy network. The mastermind, a consulate “translator,” was actually a Japanese naval officer reporting to the Washington embassy’s naval attaché.

The upended plot demonstrated how Japanese personnel parceled out cloak-and-dagger activities. While military attachés organized wide-ranging espionage (criminal, save for diplomatic immunity), their civilian counterparts mined political and strategic intelligence. Terry, for example, had three assignments: using propaganda to sway American thought leaders, accessing open sources to gather political and strategic insights, and cultivating isolationist supporters in hopes of preventing American intervention.

This was not unusual for any nation. For Japan, however, the military-civilian divide became increasingly consequential as its militarists gained control of Japan’s governance through intimidation, intrigue, and assassinations. So ascendant were they that, beginning in 1936, Japan’s war and navy ministers had to be chosen from among active duty generals and admirals. In effect, Japan’s government (nominally run along parliamentary lines) belonged to military cliques: if they ordered key cabinet ministers to resign, the government would topple.

While Terry admired the United States, he considered himself a Japanese patriot. A staunch anti-Communist, he supported Japan’s 1932 seizure of Manchuria as a bulwark against Soviet Russia. But he also believed war with America was unthinkable and viewed the Tripartite Pact as a “design for war.”

Matters converged in October 1941 when General Hideki Tojo, the cabinet’s ultra-right army minister, became Japan’s premier. Terry grew convinced that to avert calamity, DC embassy officials would have to circumvent traditional channels to prompt Emperor Hirohito’s direct intervention. Because Tojo was unquestioningly loyal to the emperor, Hirohito might yet prevent Tojo from going to war.

Hope rose with the mid-November arrival in Washington of diplomat Saburo Kurusu, dispatched as a special envoy at the request of Japan’s ambassador to the United States, Kichisaburo Nomura. Like Terry, Kurusu possessed a strong connection to the U.S.: he and his American wife Alice were parents to three children, two born in the States.

Still, war appeared inevitable. On November 26, 1941, U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull handed Nomura and Kurusu a “Ten Point Note” outlining American terms for peace, including Japan’s withdrawal from China and French Indochina. Knowing Japan’s warlords would reject the terms and attack—but not knowing when, where, or how—Nomura wired Tokyo, attempting to resign. “I will take no part in deceit,” he professed, but received no reply.

Now, Kurusu enlisted Hidenari Terasaki for one last bid. “I am thinking to have Mr. Roosevelt send a wire to the Emperor,” Kurusu confided to Terry on November 27. “No one but the Emperor can prevent war now.”

Nomura and Kurusu had earlier suggested to Tokyo that Roosevelt and Hirohito exchange goodwill telegrams—only to be rebuffed. But if another party induced Roosevelt to initiate a direct appeal, it still might work. “Can’t you somehow manage to achieve it?” Kurusu asked Terry, knowing he cultivated peace advocates who had Roosevelt’s ear. There was a risk, though: if Terry’s role was uncovered, he and his family faced disgrace, even death. But, declared Kurusu, he and Nomura had already courted treason: “It is your turn.”

Terry saw a possible go-between in Eli Stanley Jones, a well-regarded Methodist evangelist, missionary, and FDR confidant. Over lunch on November 28, Terry convinced Jones to act as intermediary, emphasizing the ploy “should be quite secret from Japanese militarists.” Jones met with Roosevelt on December 3, explaining the telegram idea came from unnamed Japanese “patriots.” When FDR replied that he was already disposed to send just such an appeal, Jones urged no revelation of the source. Otherwise, “their heads would not be worth much.”

Roosevelt’s telegram reached Tokyo at 8 p.m. on December 6. American ambassador Joseph C. Grew was to personally present it to Hirohito “at the earliest possible moment,” but Japan’s military delayed its reaching Grew. Meanwhile, Tokyo began sending a 14-part dispatch to its DC embassy, breaking off talks. Its delivery to Secretary of State Hull the next afternoon—with the Pearl Harbor attack already underway—cast infamy on Nomura, Kurusu, and all of Japan.

TERRY’S MOTIVES FOR SUPPLYING information to G-Man Roy Morgan while at the Homestead and Greenbrier thus mixed self-interest with the urge to resurrect the personal reputations of Nomura and Kurusu. Terry stressed that neither man knew about the Pearl Harbor attack in advance. Both, in his words, “felt they had lost face with all diplomats because of their presence at the State Department trying to make peace negotiations at the same time Pearl Harbor was being bombed.” Terry assailed Japan’s militarists while insisting Japan had been “boxed-in” by American intransigence.

Since Morgan and J. Edgar Hoover considered Terry Japan’s U.S. “spymaster,” they may well have viewed him as a valuable information source—perhaps even a potential double agent. But State Department officials saw him only as a threat. Indeed, when the diplomatic exchange process finally began in June 1942, they considered him among “the last persons who should be exchanged.” Nonetheless, fearing retribution against U.S. diplomats trapped in Japan, the State Department cleared Terry, Gwen, and their daughter Mariko, 9, to return to Japan.

Upon arriving in Yokohama in August 1942, the Terasakis faced wartime hardships. Helped by Terry’s brother, they initially resided in Tokyo, where Gwen’s presence caused inhabitants to stare—although more with confusion than animosity. As the war increasingly turned against Japan and conditions deteriorated, however, the family sought shelter in one of Honshu’s remote eastern seacoast villages. It was there, in autumn 1944, that Terry first spotted B-29s soaring over the coast, bound for inland cities. “This is the beginning of the end,” he told Gwen and Mariko.

In April 1945, as Japan emerged from the war’s coldest winter, the Terasakis moved to a summer house in the mountains about 100 miles northwest of Tokyo. They were lucky to find sanctuary. Ever since the March 9, 1945, Tokyo fire-bombing, thousands of refugees, many with frightful burns, had fled the cities. Years of wartime privation had taken a toll. Signs of starvation—dizziness, wan pallor, exposed rib cages, split and bleeding fingernails—set in for everyone. Terry’s once robust health succumbed to untreated hypertension, keeping him bedridden. Mariko suffered dengue fever. She recovered, but circumstances took an apocalyptic turn. Local authorities instructed the Terasakis and their village neighbors to sharpen bamboo poles as weapons to repel American invaders.

On July 26, 1945, the Allies delivered the Potsdam Declaration, warning of “utter destruction” unless Japan met four surrender demands: military demobilization, Allied occupation, purging “those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan,” and submitting to war crimes trials administered by Allied jurists. Two weeks later, Terry learned of Hiroshima’s August 6 and Nagasaki’s August 9 bombings. Finally, on August 15, word came to assemble for an unprecedented radio broadcast by the emperor. The end of the war was at hand.

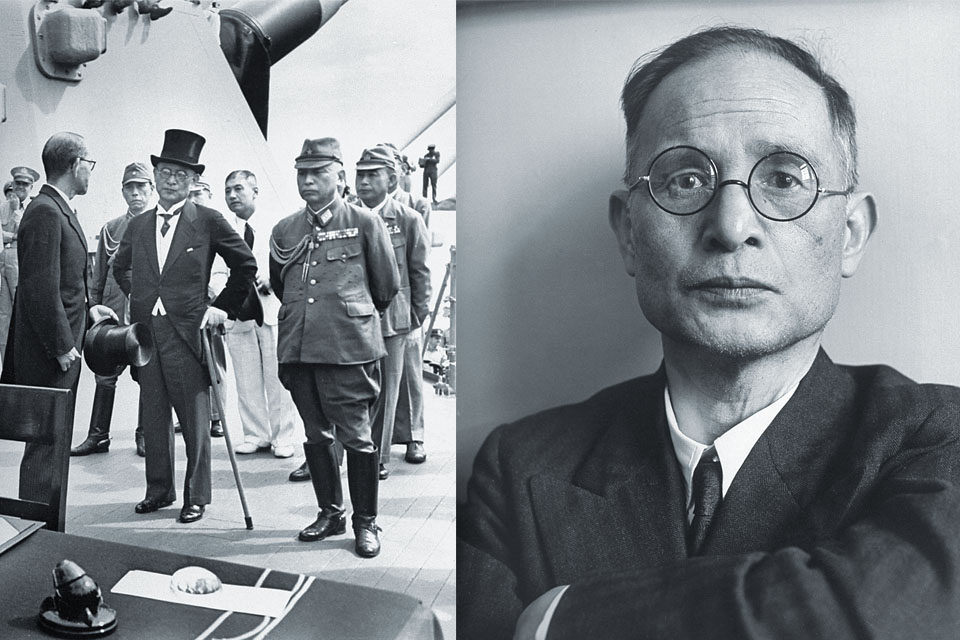

Three weeks after the formal September 2 surrender—on September 27, 1945—Emperor Hirohito first visited General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander for the Allied powers (SCAP). MacArthur greeted the diminutive emperor with easy cordiality. The general intended to use Hirohito’s popularity to smooth Japan’s postwar transition, at the same time burnishing his own reputation. But first MacArthur had to convince vengeful skeptics that Hirohito was not responsible for Pearl Harbor. It was no easy matter: 70 percent of Americans favored Hirohito’s punishment, even execution.

By then, many war crimes tribunals were well underway in jurisdictions across the Pacific, but MacArthur hoped to proceed cautiously in Japan. Still, the Potsdam Declaration demanded trials. Moreover, an August 25 communication from the London-based United Nations War Crime Commission (UNWCC) urged that Japanese war crimes suspects be apprehended “for trial before an international military tribunal.” Washington soon specified war crime categories—Class A: those planning, initiating, or waging war in violation of treaties; Class B: those violating the laws and customs of war; and Class C: those carrying out torture and murder. Subject to Washington’s determination, Hirohito’s prosecution was still possible.

Arrests got underway. Class A suspects included Hideki Tojo who, prior to his imprisonment, had tried but failed to commit seppuku—ritual suicide. That November, when the UNWCC sent MacArthur its Class A suspect recommendations, the list contained an ominous surprise. Though Hirohito himself wasn’t on the list, Koichi Kido, the emperor’s principal confidant, was. SCAP worried that Kido’s prosecution might inevitably implicate Hirohito, thereby complicating Japan’s transition to peace.

IT WAS AT THIS JUNCTURE that Terry Terasaki, though ailing and long removed from diplomatic influence, began his own resurrection. He, Gwen, and Mariko had moved back to Tokyo, surviving by what residents called “onionskin living”—selling personal belongings for food, fuel, and medicine. Fortunately for them, Terry’s fluency in English earned him an appointment as liaison between Hirohito’s court and SCAP’s General Headquarters. In that role, he met SCAP’s military secretary, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers, whom MacArthur had deputized to shield Hirohito from prosecution. Learning Terry was married to an American, Fellers asked Gwen’s maiden name. Gwen was a “Harold from Tennessee,” Terasaki told him. “We have to be some kind of cousins-in-law!” a delighted Fellers exclaimed, implying he and Gwen shared Tennessee roots.

A second stroke of fortune came on January 31, 1946, with the Tokyo arrival of Roy Morgan who, it turned out, would be chief investigator for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE)—the multinational war crimes panel set to convene that April. He and dozens of colleagues would be digging up evidence against Class A defendants. While most IMTFE investigators neither spoke Japanese nor possessed local sources, Roy Morgan was doubly advantaged. He knew many Japanese from his days at the Homestead and Greenbrier. And Terry Terasaki—whom Morgan easily tracked down via SCAP—both spoke English and was well connected.

Morgan first interviewed Terry on February 12, 1946, careful to treat him as a source, not a potential defendant. During the lengthy interview, Terry rarely mentioned Hirohito but did defend his foreign ministry colleagues and seemed ready to implicate Class A targets. The two met again six days later. This session was brief, purposely so. Terry delivered a list of individuals he—and, by clear implication, Hirohito—deemed responsible for deceitfully waging war. The 44

designated culprits included military leaders but also political operatives, rightist agitators, and industrial profiteers.

In early March, with IMFTE tribunals set for May, it became General Fellers’s turn to employ Terry Terasaki. To forestall implicating Hirohito in the trials, Fellers enlisted Terry to help craft a convincing defense. During five separate dictation sessions transcribed and translated by Terry, Hirohito delivered what has become known as his “monologue” on far-ranging matters—perhaps most consequentially, the Pearl Harbor attack. Terry periodically gave Fellers handwritten updates emphasizing the emperor’s “powerlessness” on war matters. During one monologue session, Terry even revealed to Hirohito that MacArthur had telegrammed Washington recommending the emperor’s exoneration.

IMTFE prosecutors eventually indicted 28 of the roughly 80 Class A suspects in custody. The defendants included four former Japanese premiers (among them Tojo), two foreign ministers, four war ministers, two navy ministers, six generals, two ambassadors, three financial leaders, one imperial advisor (Hirohito confidant Koichi Kido), one radical theorist, and one admiral. Scanning the names and charges, Terry—never an indictment risk himself—saw that half came from the list he had supplied Morgan back in February. While it first appeared that neither Hirohito nor Terry’s friends and mentors faced prosecution, his relief proved short-lived. Russia’s IMTFE prosecutor forced two additions. One was Mamoru Shigemitsu—Terry’s long-time patron and Mariko’s godfather.

The IMFTE trials dragged on for two and a half years, including the seven months it took the justices to reach final judgments. Terry and brother Taro would supply incriminating information (but no direct testimony) on half of the Class A defendants. For the prosecution, colluding with SCAP to absolve Hirohito, the tribunals’ most unsettling moment came in December 1947. Both prosecution and defense had anticipated that Hideki Tojo’s testimony would not implicate his beloved emperor. Instead, during cross-examination, Tojo confessed that Hirohito “consented, though reluctantly, to the war” and—worse—that “none of us [Japanese] would dare act against the emperor’s will.” In essence, Hirohito, while instrumental in ending the war, was also instrumental in permitting it.

IMTFE verdicts came down on November 12, 1948, with all Class A defendants convicted on at least one count. Seven defendants, Tojo included, received death sentences. Kido, convicted on five counts, was sentenced to life imprisonment; Shigemitsu, convicted on six lesser counts, received seven years. Those condemned to death were hanged on December 23, 1948; Kido was released for health reasons in 1953; Shigemitsu was paroled in 1950. Hirohito sidestepped war crime accountability—if not the judgment of history—and continued a largely symbolic reign until his 1989 death.

THOSE STRESS-LADEN YEARS exacted a heavy toll on Terry Terasaki. In 1946, long at risk but still just 45, he suffered a stroke. At year’s end, he suffered a “brain spasm” which kept him bedridden six weeks into 1947. By then his role with Morgan, Fellers, and the IMTFE had largely ended. When a heart attack followed that April, he seemed to recover, though he hobbled with a cane. Then, in February 1948, two months after Tojo’s testimony suggested Hirohito was complicit in war-making, Terry suffered a stroke, making it difficult to speak. Throughout, he never lacked for gratitude from Hirohito, who arranged for court physicians to attend to him. Nor did Terry lose all contact with Fellers, Morgan, or, for that matter, Eli Stanley Jones, all of whom continued warm correspondence.

In August 1949 Gwen and Mariko left Japan—Mariko to attend East Tennessee State University while Gwen resided with her mother. Both were in Tennessee when, in August 1951, Terry, 50, succumbed to a fatal heart attack.

To the last, Hidenari Terasaki seemed unwilling to concede Hirohito’s role in precipitating Japan’s war with America. Terry had risked his life just before Pearl Harbor, seeking Hirohito’s intervention to avert war. And after the war, he colluded with American authorities to absolve the emperor. Terry’s passing thus sealed a complex, if not contradictory, legacy for a man caught between loyalties to both the Eagle and the Rising Sun. ✯

For more on Hidenari Terasaki and his involvement with the war, check out the memoirs of his wife Gwen, featuring an introduction written by daughter Mariko: Bridge to the Sun: A Memoir of Love and War.