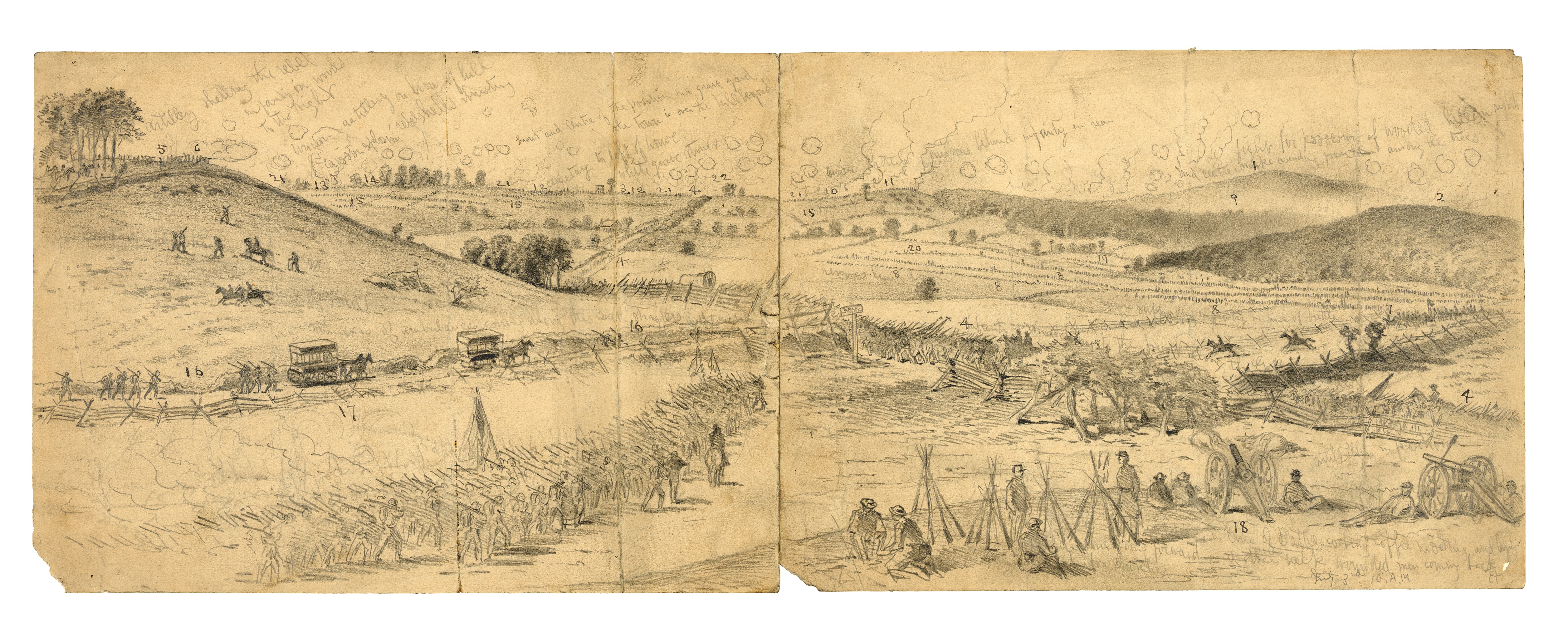

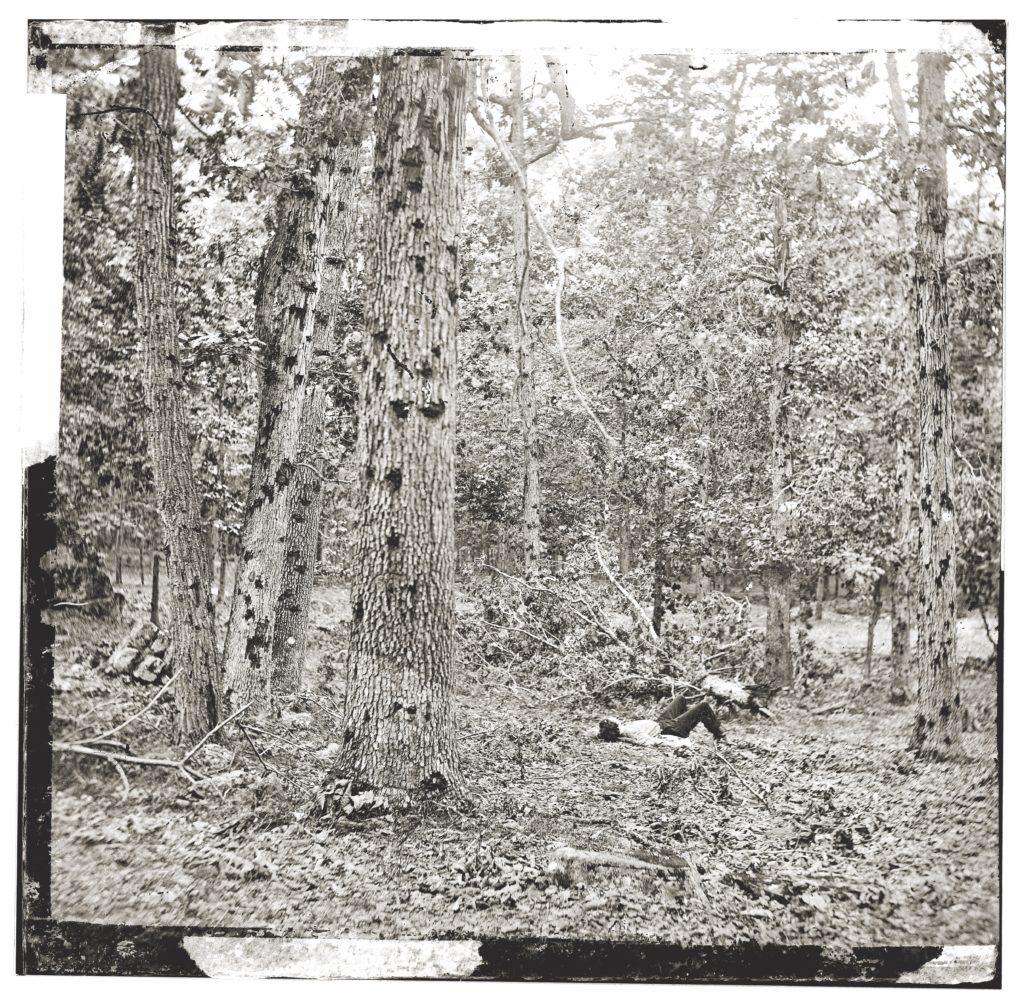

Little Round Top is one of the Civil War’s most famous landmarks. There’s no denying that the July 2, 1863, struggle on its rocky slopes helped turn the tide of the war’s greatest battle, Gettysburg. But what occurred on that mighty hill that day has been so romanticized and glorified in story and song in the 157 years since, we tend to forget that the fighting on several of Gettysburg’s other elevations was more bloody and more crucial to the Union victory. In fact, had the Confederates prevailed during repeated clashes on Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill, as well as nearby Powers Hill and Wolf’s Hill, the 20th Maine’s legendary charge down Little Round Top may well be just an afterthought today. Roughly 53,000 soldiers from 16 states collided on those four hills on July 2-3, and though often overlooked, each has its own secrets, myths, and history to tell. For some time after the battle, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill were much more popular attractions for veterans and tourists than Little Round Top. Not only were these sites initially more accessible, visitors were also able to get great views of the remnants of bullet-riddled trees; well-formed breastworks of log, stone, and earth; and the newly laid graves of many of the battle’s individual heroes. That honor, thanks to continued preservation efforts since the battle, now belongs to Little Round Top. But the four hills rightfully deserve destination status again for modern visitors to Gettysburg National Military Park.

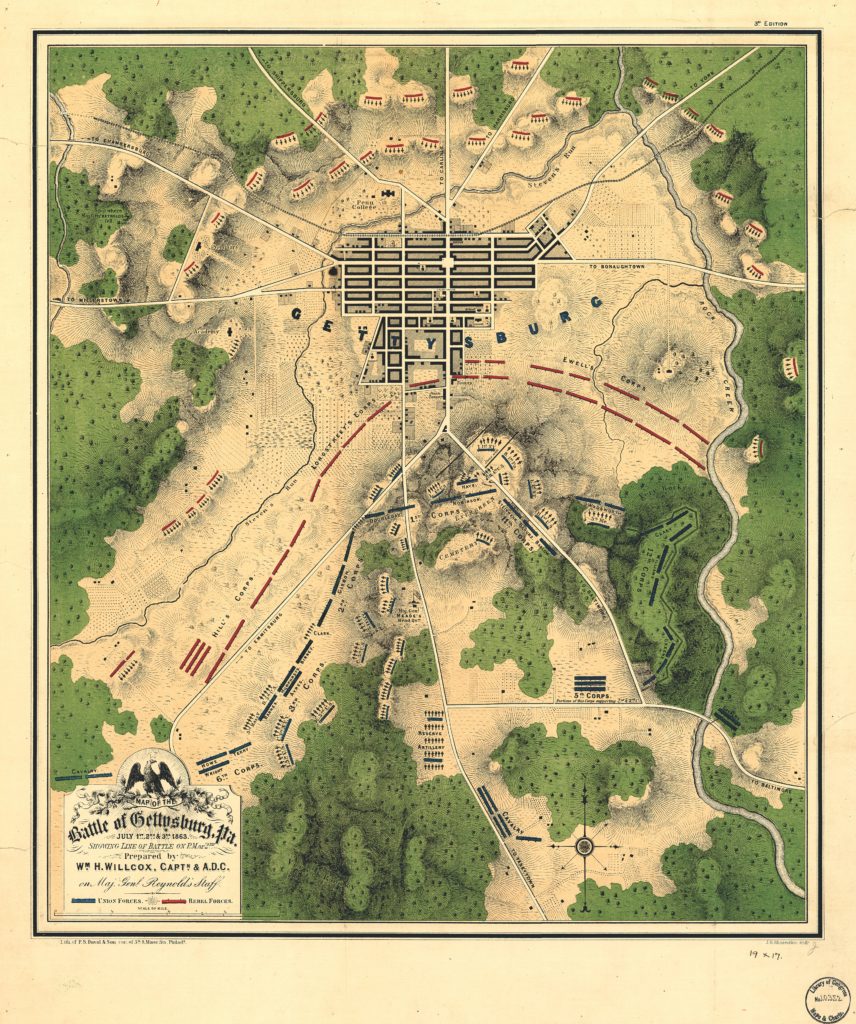

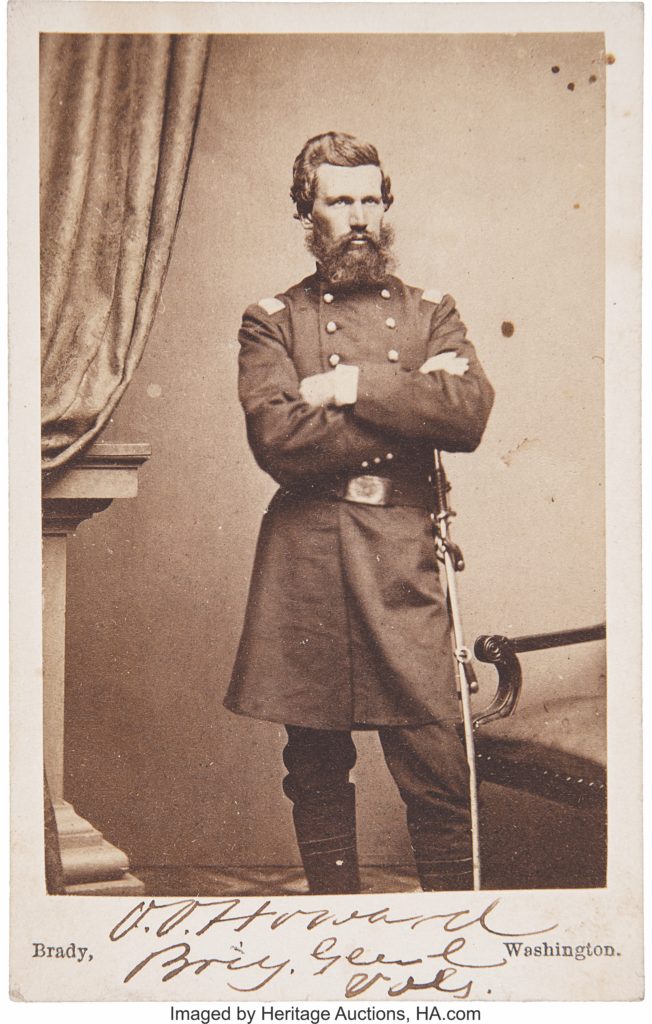

On a map, Gettysburg resembles a wagon wheel, with the town at the hub and the 10 roads leading in as the spokes. This intricate road network not only caused the battle to be fought where it was, but also dictated in many ways how it was fought. On the battle’s first day, July 1, Confederate armies approached Gettysburg from three of the spokes to the west and north while the Union approached on four spokes from the south and east. Fighting erupted west of Gettysburg and grew in intensity until some 46,000 soldiers were on the field, pitting four Confederate divisions against two Union corps. The Rebels drove the Yankees back, ultimately through Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill, where Union 11th Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, had established a reserve of infantry and artillery. More than 17,000 soldiers had been killed, wounded, or captured during the early fighting that day.

As retreating Union troops arrived on Cemetery Hill, they came under the command of 2nd Corps commander Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, who had recently arrived. Empowered by Meade to decide whether the Army of the Potomac should concentrate at Gettysburg, Hancock’s critical eye had already concluded that the hills, ridges, and open, rolling fields south of Gettysburg were the strongest natural position he had ever seen. Union troops needed to fortify the heights.

As blue-coated troops formed battle lines on Cemetery Hill, Hancock turned his attention to occupying the adjacent high ground, Culp’s Hill, as well. The general realized that if the Confederates occupied Culp’s Hill, they could make Cemetery Hill untenable. A small Yankee force on Culp’s Hill and word of reinforcements moving in from the east on York Road, however, deterred a Confederate attack that evening, as did the Southern soldiers’ overall exhaustion after one of the war’s bloodiest days.

Throughout the evening and the following day, the remainder of the Union and Confederate armies arrived on the field. The Federals now enjoyed numerical superiority, homefield advantage, inherent benefits of a defensive posture, and an interior battle line that made it easier for units to reinforce one another.

The Union “fishhook” line ran generally from near Culp’s Hill on the right flank, curved around Cemetery Hill, then moved along a line mostly on Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top on the left. Powers Hill also bolstered the Union right—an excellent artillery position sat just inside the Federal line. Confederate artillerists would also make use of Benner’s Hill along the Hanover Road. Both flanks also had wooded heights that loomed above the Union line. These peaks—Big Round Top on the left and Wolf’s Hill on the right, were mostly unoccupied by either side by the afternoon of July 2.

Three other hills—Cemetery, Culp’s, and Powers—comprised much of the Union right flank. These, as well as smaller eminences known as McKnight’s Hill (now known commonly as Stevens Knoll) and McAllister’s Hill, were proximate to Gettysburg’s top road, the Baltimore Pike—wide, well-traveled, and made of crushed white limestone.

Until the opposing armies arrived, the families that lived along the pike, or nearby, had enjoyed simple, peaceful lives. The Powers, McKnight, and Pfeffer families lived in dwellings right along the thoroughfare. James McAllister, who had been active with the Underground Railroad and abolitionist endeavors since 1836, had a mill powered by the meandering Rock Creek. The Spangler family had a spring that produced clear, cold water that often attracted local picnics. And Elizabeth Thorn, six months pregnant, was caretaker of the prominent Evergreen Cemetery, for which Cemetery Hill was named, while her husband was away in the Union Army. (He did not fight at Gettysburg.)

Howard’s 11th Corps on Cemetery Hill and the 12th Corps under Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum on Culp’s Hill primarily held the Union right on July 2. The 11th Corps had suffered terrible casualties on July 1, reducing the strength of what was already a small corps. On the battle’s second day, in fact, many of its soldiers were aligned several feet apart in some locations. The 12th Corps soldiers, on the other hand, were relatively fresh. But with only two divisions, it was the smallest infantry corps at Gettysburg.

Cannons on East Cemetery Hill belonging to the 1st and 11th corps were well protected behind half-moon-shaped “lunettes” of earth and wood, and the 12th Corps infantry had constructed substantial works of earth, log, and stone on Culp’s Hill. These works stretched around that hill’s summit and across Lower Culp’s Hill to Spangler’s Spring. Fortunately for the Federals, the country lanes and farm roads that intersected the Baltimore Pike could serve as arteries for needed reinforcements.

Heavy fighting erupted on the Union left on the afternoon of July 2. While Confederate troops captured Devil’s Den and ascended Little Round Top, Cemetery Hill remained quiet, save for occasional artillery fire. And as Confederate soldiers rolled through the Peach Orchard near Emmitsburg Road, Culp’s Hill also remained free from combat. There was movement, however. Meade didn’t think that Robert E. Lee would attack on both flanks that day and ordered five of the 12th Corps’ six brigades to reinforce the endangered Union left. That left only Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene’s New York brigade to defend Culp’s Hill. Because Greene’s 1,400-man contingent was too small to defend both Upper and Lower Culp’s Hill, the New Yorkers terminated their position with a “traverse” at a right angle to the main line on the lower slopes of Upper Culp’s Hill.

In the afternoon of July 2, two brigades of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Division attacked East Cemetery Hill, and three brigades of Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s Division advanced on Culp’s Hill, with both assaults enjoying initial success. Early’s Louisiana and North Carolina troops advanced in the twilight upon the Union line and punched through the thin 11th Corps defenses before many of the Yankees even knew they were under attack. Moving from one stone wall to another, the Southerners temporarily overran nine cannons despite hand-to-hand combat at the guns. The Confederates controlled the crest of East Cemetery Hill—the entire Union line could become unhinged if only they could hold it.

The Confederate success was fleeting, however, due to the arrival of Union reinforcements from elsewhere along its “fishhook” alignment, coupled with the unavailability of fresh Rebel troops. Notably, Union 2nd Corps brigades moved through Evergreen Cemetery and pushed back Early’s men before more Confederates could arrive to exploit or even hold the ground they had gained. The fighting on East Cemetery Hill ended with the gathering darkness, just as muzzles began to flash on Culp’s Hill.

Most of Johnson’s men encountered Greene’s formidable position on Upper Culp’s Hill. Although Greene’s men were outnumbered more than 2-to-1, the earthworks helped to minimize Union casualties while Confederate blood spilled onto Culp’s Hill’s rocky slopes. As this mighty struggle ensued, Johnson’s leftmost units came upon the abandoned Union earthworks on Lower Culp’s Hill. These Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina soldiers advanced beyond the works, but in the darkness and with relatively few soldiers, they halted, not knowing that they were merely 160 yards from the Baltimore Pike, the Union army’s lifeline. The Rebels therefore pulled back to the earthworks they had overrun, Greene held firm atop Culp’s Hill, and the fighting petered out in the darkness.

On July 3, hoping to exploit the Confederate gains on Lower Culp’s Hill, Lee ordered three more brigades to launch a renewed attack before daybreak. It wouldn’t be enough. Not only had the five 12th Corps brigades returned to the Culp’s Hill vicinity overnight, but Meade had also sent Slocum reinforcements from both the 1st and 6th Corps.

The Federals also got the jump on the Confederates by attacking first. The fighting raged for seven hours on and around Culp’s Hill. Union cannons belched support from several cannons posted on Powers Hill. Virginians and North Carolinians dueled with New York, Pennsylvania, and Maine soldiers across Rock Creek on Wolf’s Hill. By the end, not only did the Union line hold, but the bluecoats also wrested control of Lower Culp’s Hill from the weary Rebels.

About 1 p.m., probably the war’s greatest artillery exchange began—the two-hour bombardment that preceded Pickett’s Charge, which included Union cannons on Cemetery Hill. Part of Pickett’s Charge reached the slopes of Cemetery Hill before being turned back, and the assault ended in defeat for the Confederates, forcing the Army of Northern Virginia to fall back from the four hills and leave Gettysburg for good on July 4. Most of the Army of the Potomac departed the following day in pursuit of Lee’s army, which was heading back toward the Potomac River and Virginia.

The families that lived near the four hills found terrible scenes of devastation on their land. Their houses and outbuildings were used as hospitals. Culp’s and Spangler’s properties were covered with dead soldiers, some in shallow graves and others heaped in giant burial pits. Elizabeth Thorn and her father dug 105 soldier graves in three weeks. Several dead soldiers lay only partly buried near Stevens Knoll as well as near a spring owned by Edward Menchy.

For civilians, the hardships did not cease with burial of the dead and removal of the wounded. Their fence rails were mostly gone. Their wells were dry or poisoned, and their crops trampled, ruined, or gone. Hundreds of trees were torn by lead and iron. Flies conceived in the rotting carcasses of man and beast covered every structure.

While Gettysburg’s citizens were coming to terms with the battle’s toll, the preservation of the Gettysburg battlefield began just weeks after the fighting. Local attorney David McConaughy purchased four acres “east of Cemetery Hill” to preserve the natural features of the late battle. These four acres were not only the beginning of what we now know as the Gettysburg National Military Park, but these acres were the first preserved for any Civil War battlefield park. By the following year, McConaughy’s holdings had grown to include portions of the Culp’s Hill breastworks and stone walls built by Union soldiers on Little Round Top; and artillery lunettes on Stevens Knoll. A portion of Cemetery Hill had also been secured for use as the Soldiers National Cemetery.

By 1864, McConaughy’s holdings transferred to the newly formed Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA), which for the next 30 years began to create the battlefield park we recognize today. When the GBMA’s holdings were transferred to the U.S. War Department in 1895, the new Gettysburg National Military Park included some 600 acres of preserved land. The 1933 transfer to the National Park Service included more than 2,500 acres. Today, with the help of the American Battlefield Trust and numerous other partners, the park encompasses more than 8,000 acres.

_____

1. Widow Leister House Built at the foot of Cemetery Hill, this house was Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s headquarters. The Widow Leister, who had six children, returned home after the battle to find dead horses littering her property and the adjacent Taneytown Road.

2. Cyclorama building site Climb Cemetery Hill and enjoy the restored landscape: You won’t be able to tell that the former Cyclorama building was located here. The construction of the Cyclorama building in the early 1960s itself caused the removal of a 75-foot tall observation tower that had stood since 1895.

3. Soldiers’ National Cemetery What is now a peaceful resting place for thousands of souls was a terrible battleground during the conflict. The cemetery is a moving place to reflect on the cost of war.

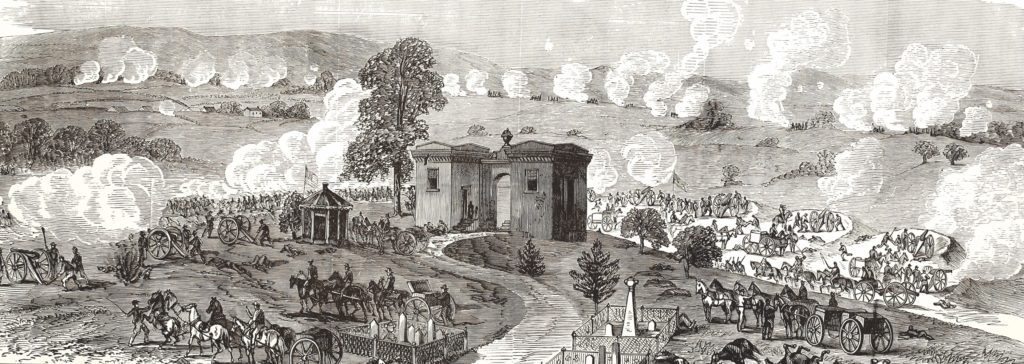

4. East Cemetery Hill The Evergreen Cemetery gatehouse is a battlefield icon, and a number of artillery lunettes are still visible on the summit where vicious fighting occurred on the evening of July 2. East Cemetery Hill was also the location of a wooden observation tower that stood from 1878 to 1895. L0ng “prop stones” that at one time held artillery tubes were reused in East Cemetery Hill’s stone walls. This portion of the hill was also where the twilight assault of Confederate brigade commander Colonel Isaac Avery occurred.

5. Stevens Knoll This knob made an excellent location for the 5th Maine Battery to rake the flank of the Confederate attack on East Cemetery Hill. Across from Stevens Knoll, you can hike the July 2-3 line of the Iron Brigade, replete with rarely seen markers to the Wisconsin units positioned there.

6. Culp’s Hill The main summit offers an interesting example of how the park roads have changed over time. The towering figure of Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene pointing toward the enemy used to greet visitors who drove to the top. Now, most visitors mainly see his posterior. Original Union earthworks and “hidden” monuments and markers can also be found in the woods along with “witness boulders” documented by photographers and a sketch artist. Walking to the end of Greene’s line, one can imagine the long-gone “traverse” that was constructed before the Confederate attack to help refuse the end of the Union line.

7. Spangler’s Spring The famous water source at the base of Culp’s Hill is charming, but stories of enemy fraternization at the water source are largely myth. The stone canopy built over Spangler’s Spring was made from granite leftover from the construction of the 44th New York monument on Little Round Top. Inside the canopy, you’ll find anchors that once used to hold a dipper, signage, and a Dixie Cup dispenser. Nearby is the postwar soldier rock carving denoting the spot where Augustus Lucien Coble of the 1st North Carolina Infantry was positioned during the horrific battle.

8. Powers Hill A number of interesting artillery monuments are on Powers Hill, and you can enjoy the cleared view to Spangler’s Spring and Culp’s Hill—the same view enjoyed by the Union gunners in 1863.

9. Lost Avenue This grassy, monument-lined strip—officially known as Neill Avenue—cannot be accessed without permission from private landowner Dean Schultz, who graciously mowed paths over his and other private land leading to Gettysburg’s most obscure road, known as Lost Avenue. Those who get the chance to go on special tours to Lost Avenue, however, will see numerous monuments and an intriguing sign at the southern end of the avenue.

10. McAllister’s Dam The remains of the dam can still be seen on Rock Creek, and the remains of McAllister’s Mill are visible from a distance on private land. The nearby Mulligan McDuffer’s mini-golf course, in the shadows of Powers Hill, is now owned by the American Battlefield Trust.

Garry Adelman is chief historian at the American Battlefield Trust, vice president of the Center for Civil War Photography, the award-winning author of more than 50 books and articles, and has been a licensed battlefield guide at Gettysburg for the past 25 years. This story appeared in the February 2020 issue of Civil War Times.