Writing from his home in Florence, Italy, in September 1891, retired U.S. Army officer Truman Seymour struggled to find the words. “I am so feeble, so broken down, so heavy-hearted,” he told Parmenas Taylor Turnley in response to the news that Turnley’s youngest son, just 16, had died from typhoid fever. “[S]ince your letter came this morning, I have been wandering about the house, trying vainly to realize the incomprehensible fact, and crying until I can hardly see to write.”

At the time, Seymour was living in Italy as an artist, suffering from Bright’s disease, which would factor in his death only one month later. Having lost his only son 32 years before, Seymour looked upon Turnley’s boy as one of his own. Turnley, who graduated with Seymour in West Point’s famed Class of 1846, had honored his friend by giving his son the middle name Seymour.

“Feeble and reeling on the brink of his own sepulcher, he answered my letter the same day,” recalled Turnley, who, in an effort to reveal the “true character, life and being” of this enigmatic Union general, made sure the information was prominently shared in Seymour’s obituary.

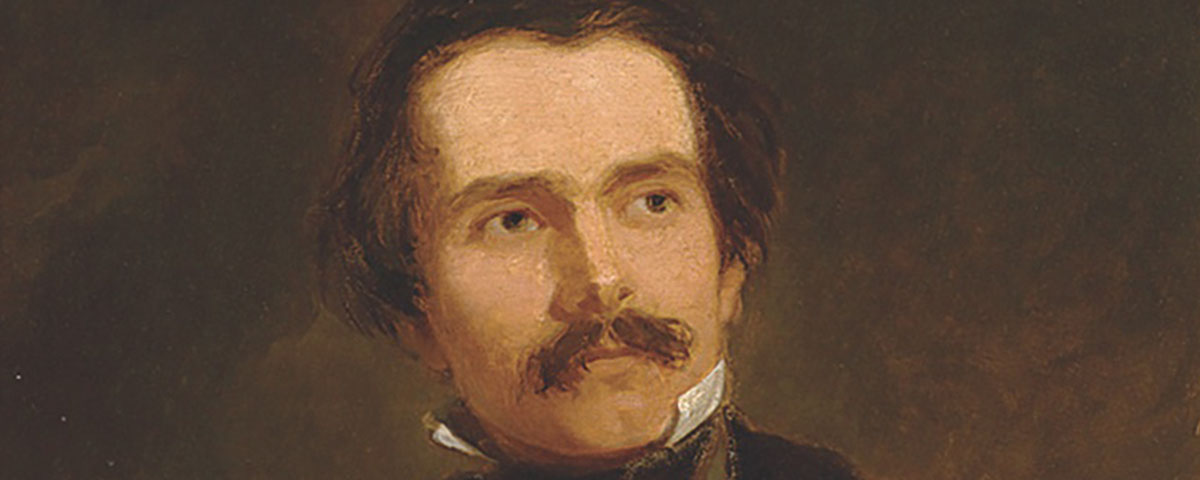

Born September 24, 1824, in Burlington, Vt., Seymour was a descendant of an early colonial settler, Richard Seymour. Appointed to West Point in June 1842, Seymour established himself as one of the most talented artists in the academy’s history under the tutelage of Robert Walter Weir. Seymour proved an accomplished warrior as well, serving with distinction during the Mexican War. In 1850, he returned to West Point to serve as an assistant professor of drawing under Weir and even married his mentor’s daughter, Louisa.

At the war’s outset in April 1861, Seymour was one of nine officers in the Fort Sumter garrison during the Confederate bombardment. Commissioned a brigadier general in April 1862, he would command a brigade in the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign, at Second Bull Run, and at Antietam. From November 1862 to March 1864, Seymour served in the Department of the South, severely wounded in the historic Union assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. As commander of the District of Florida, he led Union forces during the defeat at Olustee, Fla., in February 1864.

Back in the Army of the Potomac by May, he was captured at the Battle of the Wilderness. Exchanged in August, he served as a division commander for the remainder of the war.

Seymour moved to Europe after retiring from the Army in 1876 to pursue his passion for art. The Seymours toured England, France, Spain, and Italy, befriending various European artists along the way. Seymour filled his sketchbooks with scenes of the exotic places he visited and painted numerous watercolors. His health failing, Seymour made Florence his home in 1885. Upon his death, he was buried in Florence’s Cimitero Evangelico degli Allori—a cemetery where a fellow Civil War veteran, Colonel Adolphus Buschbeck, is also interred.

Louisa would spend the final 28 years of her life in the United States. She is buried in West Point’s Cemetery alongside her only child.