In July 1918, four months before the end of World War I, a cadre of British officer POWs staged a daring escape from the heart of Germany

During World War I, Allied soldiers and aviators who avoided death sometimes found themselves imprisoned in Germany’s archipelago of POW

camps, often in abominable conditions. The most infamous was Holzminden, a landlocked Alcatraz of sorts that housed the most troublesome, escape-prone prisoners. Its commandant was Hauptmann Karl Niemeyer, a boorish, hate-filled tyrant. Tall and stout, Niemeyer was a bully of the first order. He often skulked bowlegged about the camp, chomping on a cigar while looking for trouble. No slight from a prisoner—a weak salute, a roll of the eyes, an impertinent remark—went unnoticed or unpunished. He scolded and threatened prisoners with a zeal that left him red-faced and panting for breath. In his previous roles at different camps he had been loathed by his charges. His elevation to commandant only deepened the prisoners’ contempt for him.

In the summer of 1918 a group of Allied prisoners led by British Royal Flying Corps pilot Capt. David Gray hatched an elaborate escape plan—right under Niemeyer’s nose. Their plot demanded a risky feat of engineering as well as a bevy of disguises, forged documents, fake walls and steely resolve. But before they could make the necessary 150-mile dash through enemy territory to neutral Holland, Gray and his half-starved fellow prisoners had to first break out through a tunnel that had taken months of torturous digging and near-death moments—and then navigate beyond the German watchtowers and round-the-clock patrols.

Escape was the plan—and humiliating Niemeyer was icing on the cake.

Tuesday, July 23, 1918, may have looked like any other day at Holzminden. The prisoners were roused from their beds and herded onto the Spielplatz (parade ground) for morning roll call. They drank tea and ate stale biscuits for breakfast before waiting in line for a parcel or letter. Most shuffled about the yard and watched an impromptu game of soccer before having their usual tasteless lunch. But some watched carefully for any change in the guard. Most prisoners read in their rooms, debated the merits of the American Army, played poker or just sat. But some checked for signs of a coming storm. There was hushed talk of crossing the Weser River, of the dogs the guards used for manhunts, of German soldiers on night watch in the town. Then came the evening roll call, a final harangue from Niemeyer. Murky brown soup for dinner, since they needed to save their own food supplies for their run.

“Tonight,” was the whisper among the tunnelers. It would be tonight.

At 6 p.m. Gray assembled the team in the barracks and told them to be ready after lockup. He needed the halls and rooms swept of any officers who did not belong in Block B. Lookouts at the entrance were necessary to deter interlopers. The men were anxious, thinking of the perils that lay ahead.

As the dedicated team of tunnelers left to prepare, Gray met quickly with Capt. Hugh Durnford, an Anglo-Indian artillery officer who spoke Hindi. Both were close in age and experience and style—including their well-trimmed mustaches and military bearing. Durnford had known about the tunnel for months but considered it nothing but a fool’s errand that was sure to be discovered. But now, with the tunnel finished and ready, he regretted not being on the escape list. Nevertheless, he swore to do everything he could to see it come off smoothly. “If [Block] B harbored no aliens that night,” Durnford later recalled Gray telling him, “the escape would take place.”

As the sky darkened and clouds swept across the rising moon, Gray waited with the others, passing the time until lockup examining their maps again, going over their plan for the first few hours of their run to Holland. Second Lt. Caspar Kennard wandered about the small room, practicing for his upcoming role as “the madman.” He rolled his eyes, jabbered incoherently, blew spit bubbles and whimpered like a wounded animal. “Oh, shut up and listen for a minute,” Gray interrupted, drawing their attention back to the maps. Even the leader was feeling the tension.

In fact, officers throughout Block B were feeling nervous. They ate whatever they could stomach and smoked. Some drank a glass of wine to bolster their courage. Others abstained, believing that a drink would dull their wits when they most needed them. Sublieutenant James Bennett, a Royal Naval Air Service observer, remained sober. He imagined his planned journey through the tunnel and the subsequent swim across the Weser. Once on the opposite bank he hoped to navigate quickly and quietly through the surrounding fields of corn and rye, eluding any pursuers. Lieutenant Col. Charles Rathborne paced through the barracks hallways before stopping in to say goodbye to Durnford. When he put on his feathered cap and glasses to show his disguise, Durnford praised his look as “wonderfully Teutonic” and wished him luck.

At 9 p.m. the lone German guard shut and locked the door to Block B with the resonating clang that never lost its impact for the prisoners. With one more hour to wait, they put on their escape outfits and layered their pajamas over them to keep the clothes clean on the crawl through the tunnel.

As the minutes ticked away, the wind continued to gust, and occasional lightning illuminated the sky in the distance. Rain had yet to fall, but it surely would. So if the prisoners did manage to break out from the tunnel, the storm would leave them soaked to the bone before they even reached the Weser. Finally, at 10 p.m., as was his routine, the German guard finished his last check and left the building. The door locked shut again.

Fifteen minutes later Gray informed Durnford that all was clear. Time to go. Durnford made his way through the corridors, spreading the word that the plan was proceeding and that each man should be ready when his time came.

The tunnelers, carrying their boots to keep quiet and with their kit bags slung over their shoulders, crept out of their rooms and climbed the stairwell to the attic of Block B, where one of the rooms had been fitted with a hidden panel. As the team assembled one last time, there was no need for speeches or last-minute instructions. They just wished one another well.

Outside, the storm howled. As one officer later described it, thunder cracked and boomed like the “finale of a gigantic orchestra.” The tunnelers could not have asked for better weather to mask their movements on breakout night.

Given his prowess as an Army sapper, Lt. Walter Butler was chosen to go first and dig to the surface. Butler muttered a short prayer before pushing his kit bag into the tunnel and following it in. The only other officers in the chamber, Lt. Andrew Clouston and Capt. William Langran, would join him after 30 minutes, giving Butler time to cut through to the surface. The first stretch, with its downward slope, was easy going. Although he had crawled his way through the top scores of times, this time was different: The others were depending on him like never before. He needed to move quickly, and his burrowing to the surface had to escape detection from the guards. Otherwise, nine months of heartache and labor would amount to nothing. Worse still, it might get them all shot. With his kit in one hand and a candle in the other, he efficiently squirmed through the tunnel, praying as he went.

When he reached the tunnel’s end, Butler’s hair and collar were soaked in sweat. Without pause he started digging a path straight upward. His trowel made easy work of the soft dirt and clay, which poured down on top of him—coating his hair, covering his eyes and ears, trickling down his neck—yet he paid no mind to the discomfort. The quicker he bored to the surface, the more time they would all have to get away from Holzminden. Any delay would mean fewer officers would be able to escape.

Finally reaching the surface, Butler took his first breath of fresh, free air. At best his hole was only 6 inches in diameter, but it was a start. Rain pelted down, and the light from the camp arc lamps shone brightly. Now able to kneel up in the tunnel and lengthen his arm, he began digging faster, energized that freedom felt within reach.

After 30 minutes Langran and Clouston joined him as planned, and they packed the earth piling up around Butler into an offshoot chamber to get it out of the way. Clean air poured into the tunnel from the expanding exit. By 11:40 p.m. the hole was wide enough for a man to climb to the surface.

Butler first pushed his kit out of the tunnel into the field and then, using his arms and feet to brace the side of the hole, slowly rose. His hair was sopping, and rain mixed with dirt poured down his grimy face. As he eased his head out of the tunnel, he was pleased to discover that the exit was where he wanted it to be.

There was no time to rest before his partners joined him. He crawled forward on his belly to the first row of beans. Hiding amid the dense leaves, he searched for the German guard who was stationed outside the wall. The arc lamps’ light and the shadows made it hard to see. As far as Butler knew, the German might have detected some movement and be standing still, looking directly toward the tunnel exit. Then the guard coughed and Butler spotted him against the darkness of the wall. He was pacing back and forth, clearly unalarmed. At that moment the rain halted, the clouds parted and moonlight shone down on the field.

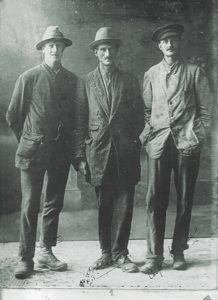

fellow escapees wore civilian clothes during the breakout. (Hugh Lowe)

Minutes before, Pvt. Ernest Collinson, a Royal Army Service Corps driver, had been staring toward the bean rows from the window of Block B’s orderly quarters. For more than a half-hour he had squinted through the darkness for any sign of Butler. By now he should have cut through to the field, Collinson thought. Perhaps he had missed him because of the lights and the sheeting rain. Butler may have already moved on to the rye field or be moving toward the Weser, but Collinson had no way of knowing for sure. Gray and his team needed to know definitively that Butler had made it out before they proceeded into the tunnel themselves. They were depending on Collinson.

Gradually, as the moon broke through the clouds, Collinson spotted Butler’s hunched figure amid the bean rows. The figure crawled toward the stalks of rye, followed soon after by two others. Collinson hurried from his observation post toward the stairwell. In his socks he barely made a sound. On the attic floor he clambered through the small door, quickly crossed the eaves and knocked on the 2-foot square panel leading into the officers’ quarters. Collinson reported that Butler had made it. Little else needed to be said.

As the next batch of tunnelers began filing into the eaves, Collinson was impressed by the sight of 2nd Lt. Cecil Blain’s civilian suit underneath his pajamas. “Mr. Blain,” Collinson said. “You’re all togged up like a proper toff.”

Blain widened his arms, as if offering an embrace. “Dance?” he asked.

The officers laughed quietly and continued down the eaves. When Collinson offered to lead them down to the entrance chamber, Kennard replied, “Don’t bother, Collinson, we’ll see ourselves out.” They shook hands, and Gray thanked Collinson for his efforts.

“The best of luck to all of you,” Collinson called to the men. “And don’t forget to drop my missus a line when you get home.”

Blain was the sixth man into the tunnel. “Chocks away,” he said as he tossed his kit into the hole, but the bravado he had maintained throughout the evening quickly dissipated. Kennard followed, then Gray. Those who had gone before them left a few tin-can lamps burning along the path, but given the passage’s many kinks and turns, the three of them crawled mostly in the dark.

In the lead, Blain kept to a good pace, pushing his rucksack ahead of him as he wriggled onward. When his jacket caught on a rock or when he slowed to take a breath, he felt Kennard’s bag press up against his feet. During one stretch, which was illuminated by dim candlelight, Blain suddenly found himself staring straight into the face of a rat, its eyes like black beads. Although he had encountered his share of rodents in the tunnel, they always sent shivers down his spine. Before he could brush the rat away with his arm, it disappeared into the darkness ahead, no doubt sensing the exit into the field.

As he continued, he found himself panting, with his arms growing heavy from pushing his kit. In all his shifts underground, the tunnel had never felt so long nor looked so ominous. The shadows cast about the narrow, misshapen bore resembled monsters waiting to attack. He wanted nothing more than to be free of it. Then up ahead he saw a light shining down into the tunnel. The Germans must have found the sap exit, he thought. He would have scrambled away—if there was anywhere to go. Instead, he lay flat and motionless as a stone.

“What’s up?” Kennard asked, his voice little more than a muffled mutter. His claustrophobia was making him more anxious than ever. Blain angled his head to the side, his eyes adjusting enough to the light to see that it was simply the glare of the arc lamps through the hole. But he found himself immobilized all the same.

Behind him, Gray demanded to know what was going on. Kennard thumped the back of Blain’s boots. Finally, the young pilot wrenched free and moved ahead again, his heart beating like a drum. After several more feet Blain finally reached the tunnel exit and breathed a cool draft of fresh air. He rose to his knees, then to his feet in what he figured might well become his vertical grave. Only the encouragement from Kennard and Gray kept him moving.

Blain eased his kit out into the field and then squirmed upward. As his head rose out of the tunnel, he expected to hear the crack of a gunshot. When he heard only the patter of raindrops, he finally calmed. It was almost 1 a.m.

Sixty yards away the arc lamps swinging in the wind cast Holzminden in a ghostly white pallor. The lone guard continued pacing back and forth by the wall, his rifle tucked under his arm, his coat collar tight around his neck. The wind blew from the southwest, providing them audible cover for movement. Blain carefully and slowly eased himself up onto the field. He kept his body low as he scrambled through the rows of beans. When he looked back toward the tunnel exit, he saw Kennard, Gray and the others emerge in close succession. To Blain it looked like their heads and feet were almost connected, resembling a huge, mud-splattered crocodile. He almost laughed at the curious but exhilarating spectacle.

As he reached the stand of rye, some fallen stalks rustled beneath him. Even with the steady beat of rain, the sound met Blain’s ears like a series of

outside the camp’s perimeter fence. (Neal Bascomb)

small detonations. He waited at the edge of the field for Gray and Kennard to reach him. In whispers they debated advancing into the rye or else crawling along its edge until they were far enough away from the camp. Gray decided that proceeding directly through the stalks was the quickest way, and he was sure that the rainfall and wind would sufficiently drown out the noise of the stalks underfoot.

The three threaded their way into the rye field, with Blain convinced the guard would soon hear their movements and set the dogs on their trail. When no cry of alarm was raised, he relaxed enough to straighten up from his crouched walk and hasten his pace.

After traversing the rye field they came to the main road that ran between Holzminden and Arholzen, the nearest town to the northwest. They knew that the police patrolled the stretch of road on bicycles at night. So the escapees waited at the side of the road until they were sure the coast was clear.

After Gray led them northward through more fields of rye and corn to the top of a low hill, they dropped their rucksacks and took a brief rest. They had been on the run for a half-hour. In the distance the town of Holzminden looked to be floating in a sea of surrounding darkness. The three officers savored their freedom at last. They were again the masters of their own fate. The air they breathed never tasted fresher; the hunks of Caley’s Marching Chocolate never sweeter.

“Bet Niemeyer wouldn’t be sleeping so well if he knew where we were,” Blain said.

“Let’s hope nothing disturbs his slumbers until morning,” Kennard replied.

“Just let’s make sure,” Gray said, “we never see that bastard again.”

They tramped down the hill to the Weser River, a natural barrier to any westward escape. The Germans routinely patrolled the bridges over it, and its fast, deep waters had delayed—or altogether foiled—earlier runs from Holzminden. They needed to cross to its opposite bank before first light of dawn, at roughly 4:30 a.m. Otherwise, they were sure to be recaptured. The escape artists of Holzminden still had a long road ahead.

Neal Bascomb [nealbascomb.com] is the award-winning, bestselling author of The Winter Fortress, Hunting Eichmann, The Nazi Hunters, Red Mutiny and other nonfiction books. A former journalist, he is a widely recognized speaker on war and has appeared in a number of documentaries. To learn more about the Holzminden escape, read Bascomb’s new book, The Escape Artists: A Band of Daredevil Pilots and

the Greatest Prison Break of the Great War.

Excerpted with permission from The Escape Artists: A Band of Daredevil Pilots and the Greatest Prison Break of the Great War, by Neal Bascomb, © 2018 Neal Bascomb, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, New York, $28