A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: Because of a production problem, a portion of this article was omitted from the January 2012 issue of America’s Civil War. It follows here in full.

During the first three months of 1861, New York City boldly flirted with leaving the Union. The reasons were decades in the making, but the sentiment was never more pointed than on January 6, 1861, when New York Mayor Fernando Wood addressed the city council. “It would seem that a dissolution of the Federal Union is inevitable,” he observed, noting the sympathy joining New York to “our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States” and suggesting that the city declare its own independence from the Union. “When Disunion has become a fixed and certain fact, why may not New York disrupt the bands which bind her to a venal and corrupt master—to a people and a party that have plundered her revenues, attempted to ruin her, take away the power of self-government, and destroyed the Confederacy of which she was the proud Empire City?”

Wood was preaching to the converted. Then, as now, New York City was the nation’s financial hub, and had made its reputation—and the lion’s share of its revenues—by supplying goods and services to the slave South. Most New Yorkers were decidedly pro-Southern and for years leading up to Abraham Lincoln’s election, two scoundrels—Wood and U.S. Marshal Isaiah Rynders—nurtured pro-slavery practices, both legal and illegal, in the city.

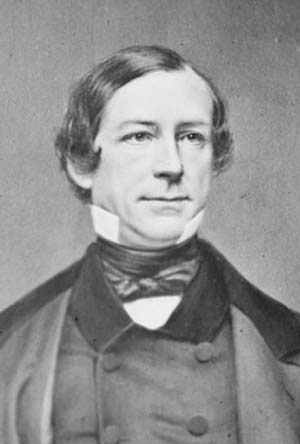

Corrupt to the core, three-time mayor Wood was handsome and charming—and a crook and a racist. He bribed the police, made a fortune selling public offices and offered immigrants naturalization in exchange for their votes. As Harper’s Weekly reported in 1857, New York under Wood was “a huge semi-barbarous metropolis…not well-governed nor ill-governed, but simply not governed at all.”

“Fernandy,” as Wood was known to fellow New Yorkers, owed much of his success to Rynders. A Virginian by birth and a gambler by trade, Rynders had reportedly left the South one step ahead of a lynch mob before landing in New York, where he quickly became a gang boss and a “fixer” for the crooked Tammany Ring, the Democratic political machine that ran the city. There was not an election that wasn’t influenced—either through bribery or force—by “Captain” Rynders and his gangsters.

“Fernandy,” as Wood was known to fellow New Yorkers, owed much of his success to Rynders. A Virginian by birth and a gambler by trade, Rynders had reportedly left the South one step ahead of a lynch mob before landing in New York, where he quickly became a gang boss and a “fixer” for the crooked Tammany Ring, the Democratic political machine that ran the city. There was not an election that wasn’t influenced—either through bribery or force—by “Captain” Rynders and his gangsters.

Wood virulently opposed the anti-slavery movement, and at his instigation, Rynders would send bully boys to break up meetings of reform groups and disrupt speeches by the likes of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Wood believed black people were racially inferior and regarded slavery as a “divine institution.”

Sadly, many New Yorkers had a similar view of slavery—or at least a high regard for the profits to be made from it. “New York belongs almost as much to the South as to the North,” observed the editor of the New York Evening Post. The city’s businessmen marketed the South’s cotton crop and manufactured everything from cheap clothing for outfitting slaves to fancy carriages for their masters. Wood himself called the South “our best customer. She pays the best prices, and pays promptly.”

Wood’s political base included the city’s gentry and businessmen who made their living from the slave industry as well as the working class whose jobs would be threatened by freedmen surging North. The mayor was not far wrong when he claimed “the profits, luxuries, the necessities––nay, even the physical existence [of New York] depend upon…continuance of slave labor and the prosperity of the slave master!”

New York was not only a major commercial supply hub for the South’s legal institution of slavery; it was—and had been for many years—the epicenter of America’s illegal slave trade. Although the state of New York had voted in 1827 to abolish slavery, New York City traders continued to provide slaves––first to the South, then to Brazil and Cuba––right up to and during the Civil War. Whether as investors, ship owners or captains and crews, New Yorkers promoted, enabled and carried on the traffic in humans. Of all the cities in America, New York was the most invested in the transatlantic slave trade.

New York’s ship owners built their vessels to accommodate large slave cargoes; its businessmen financed and invested in the voyages and its seamen made the trips. The profits realized from a single slaving expedition were staggering: A slave purchased for $40 worth of cloth, beads or whiskey would sell for between $400 and $1,200 on the blocks of Charleston, Mobile, Rio de Janeiro or Havana. With the sale of an average cargo of 800 slaves bringing as much as $960,000—a sum equalling tens of millions in today’s currency—many a ship owner, investor and captain grew wealthy from the proceeds of a single successful voyage.

And in the unlikely event that a slave ship was captured at sea and subjected to proceedings in New York’s courts, the city’s bondsmen stood ready to falsify bond transactions, freeing the vessels for future slaving voyages. In the first 60 years of the 19th century, New York City financed and fitted out more slaving expeditions than any other American port city, North or South. Between 1858 and 1860, New York launched nearly 100 slave ships. And in keeping with the latest maritime technology, many of these vessels were New York–built steamers that could handle much larger “cargoes” than the earlier sailing vessels. It was all about business; the more Africans that could be crammed aboard, the greater the profit.

“Few of our readers are aware…of the extent to which this infernal traffic is carried on, by vessels clearing from New York, and in close allegiance with our legitimate trade,” the New York Journal of Commerce wrote in 1857, “and that down-town merchants of wealth and respectability are extensively engaged in buying and selling African Negroes, and have been, with comparative little interruption, for an indefinite number of years.” Everyone knew who these merchants and traders were. Despite the pretense of secrecy, some slave traders occupied lofty positions in New York society and maintained visible offices along South Street. One such “businessman” also served as the Portuguese consul general in New York.

By 1860, New York City’s reputation for official corruption and leniency toward slavers was unrivaled. Putting money into slaving voyages was considered a good investment—much as one would invest today in AT&T or Microsoft—and although the practice was illegal and the transgressors were widely known, no efforts were made to apprehend either the investors or the traders. Amazingly, it was generally viewed as a “victimless” crime. In fact, whenever a voice was raised to condemn the practice, New York’s businessmen were united in their opposition to change.

Arrests at sea were rare, thanks to the gross inefficiency of the Navy’s tiny, antiquated and unmotivated African Squadron. Navy vessels didn’t try to capture slave ships. Their commanders acted under orders to protect the rights of American merchant seamen—in other words, keep the British off our ships. And if they happened to come across a slaver, all well and good: Arrest it. Their record of seizures was predictably abysmal. During a six-year period in which its British counterpart seized more than 500 slave ships containing some 40,000 captives, the American fleet captured only six––one per year. And on the infrequent occasions when slavers were arrested and brought to trial in federal court, they were almost invariably released or given a token slap on the wrist.

In New York City, where most of the Northern prosecutions took place, hardly any of the few indicted were actually convicted. Of the 125 seamen prosecuted as slave traders during the 24 years before the Civil War, only 20 were sent to prison—with sentences averaging two years apiece. Ten of these received presidential pardons and three more, facing the possibility of the gallows, were allowed to plead to lesser charges. Although slave trading had been a capital offense since 1820, not a single slave trader had been executed by 1860. American judges and juries simply refused to hang American sailors for bringing slaves from Africa to Cuba or Brazil at a time when it was perfectly legal to sell one’s slaves from, say, Virginia to Louisiana.

Skilled attorneys were employed anonymously by New York’s established slave traders to defend accused captains and their crews. Ironically, a number of these lawyers were former U.S. and assistant U.S. attorneys, whose job it had been to prosecute the very men they were now hired to get off. The pay was considerably better and the verdicts almost certain to run in their favor. Their defense arguments were transparent and absurd; nonetheless, New York’s judicial system regularly allowed slavers to walk out of court scot-free.

But attorneys did not rely on their arguments alone; payoffs and violence helped. It was common practice for public servants at all levels of city government to be on the take. A June 1860 editorial in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune described the state of “The Slave Trade in New York”:

It is a remarkable fact that the slave traders in this city have matured their arrangements so thoroughly that they almost invariably manage to elude the meshes of the law. Now they bribe a jury, another time their counsel or agents spirit away a vital witness….The truth is, the United States offices in Chambers Street…have become thoroughly corrupt….To break up the African slave trade…it will be necessary to purge the Courts and offices of these pimps of piracy, who are well known and at the proper time will receive their just des[s]erts.

No “just desserts” would be forthcoming, however, so long as James J. Roosevelt was U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. He had been a member of the State Assembly, a congressman and a justice of the New York Supreme Court. He was now old, tired, facing retirement and not about to undertake the prosecution in a capital trial of an accused slave trader. He also shared President James Buchanan’s avowed refusal to hang a man for slave trading, despite the law.

Before the game-changing election of 1860, Wood bought the New York Daily News for his younger brother, Benjamin, who was as racist as his big brother. During Abraham Lincoln’s campaign, Benjamin Wood churned out an endless stream of caustic editorials, howling that “if Lincoln is elected you will have to compete with the labor of four million emancipated Negroes,” and “we shall find Negroes among us thicker than blackberries.” As for the city’s businessmen, the prospect of losing their biggest client—the South—was terrifying indeed, and Southern growers and newspapers knew it. One New Orleans editor put it succinctly: Should New York lose the South’s trade, its “ships would rot at her docks; grass would grow in Wall Street and Broadway, and the glory of New York, like that of Babylon and Rome, would be numbered with the things of the past.”

In December 1860, with Lincoln elected and the threat of secession fast becoming reality, some 2,000 terrified New York men of commerce gathered in support of the South—and of secession. “If ever a conflict arises between the races,” proclaimed attorney Hiram Ketchum, “the people of the city of New York will stand by their brethren, the white race.” These men—and thousands like them—owed their livings to the cotton trade, and they were willing to do virtually anything to ensure the Southern connection remained intact.

To some extent, their fear was justified. The South did, in fact, owe New York’s coffers tens of millions of dollars. When South Carolina’s legislature dissolved its bond with the United States on December 20, it foreshadowed a series of events that threatened to plunge New York into severe economic crisis. Clearly one of the first commercial steps the seceded states would take would be to repudiate their debts to Northern suppliers and business associates.

Mayor Wood acted quickly. When he declared national disunion to be a “fixed fact” on January 6, he also proposed that Gotham declare itself an independent commonwealth, to be called the Free City of Tri-insula, Latin for “Three islands”—Long, Staten and Manhattan. As its own sovereign city-state, it would be free to “make common cause with the South” and deny Federal troops the right to march through the city.

Incredibly, the Common Council—a notably corrupt lot of politicians informally dubbed “The Forty Thieves”—actually approved Wood’s proposal and had copies printed and widely distributed. For a brief period, it appeared as if the North’s major commercial port and business center would join the South in rebellion. The council reversed itself only after the attack on Fort Sumter in April; had they stuck by their original decision, the outbreak of war would have made them all traitors and arguably put them in line for the gallows.

But when the Lincoln administration took office in 1861, changes came to New York as well. Roosevelt and Rynders—both political appointees—were replaced by two honest and dedicated men: U.S. Marshal Robert Murray and U.S. Attorney E. Delafield Smith. At the next mayoral election in 1862, the Democratic ticket was split beyond reconciliation, and to his surprise, “Fernandy” Wood was replaced by a staunch Lincoln Republican, George Opdyke.

Smith immediately set out to drive the slave traders from New York. He convicted and jailed Albert Horn, a local ship owner. Horn’s 572-ton steamer, City of Norfolk, was captured at sea with 560 slaves aboard. Smith also jailed Rudolph Blumenberg, a bondsman responsible for bailing out captured slave ships, enabling them to return to Africa. And most dramatically, in 1862 Smith—with the support of President Lincoln—hanged a slave trader, a New England sea captain named Nathaniel Gordon, who had been arrested off the West Coast of Africa with nearly 1,000 captives—half of them children—in the hold of his small ship.

The execution sent shock waves through New York’s slaving community. The traders were stunned; New York’s newspapers exulted. “[T]he majesty of the law has been vindicated, and the stamp of the gallows…set upon the crime of slave-trading,” the New York Times reported, “And it was time.”

“Since entering upon the duties of this office, I have made an earnest effort…to check the Slave Trade from the Port [of New York],” wrote Rynders’ replacement, U.S. Marshal Murray, to his superior, the secretary of the Interior. “This City had become the principal depot for vessels in this traffic, and I felt that here the attempt must be made to arrest [it]….I am satisfied that the parties interested have removed their operations from New York to the ports of New London, New Bedford, and Portland.”

Once the war began, New York rallied to the cause and supplied invaluable troops and support to the Union effort. In the words of historian Murat Halstead, “The thunder of Sumter’s guns waked the heart of the people to passionate loyalty. The bulk of the Democrats joined with the Republicans to show by word and act their fervent and patriotic devotion to the Union.” The city came alive with mass meetings and patriotic rallies—and, never one to miss an opportunity, one of the most vociferous in his support of the Union and condemnation of the rebellious South was Fernando Wood.

But as the war dragged on, most New Yorkers held fast to their Democratic roots, their rabid hatred of blacks and their opposition to Lincoln. In 1863, when conscription became an issue for working men throughout the North, it was a mob of New York residents that tore up the city’s streets, burned out its buildings and left dozens of dead in its wake. By the war’s end, New York had much to celebrate—and much to forget.

Historian and author Ron Soodalter is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War.