A new biography highlights General Maxwell Taylor’s influential role in U.S. strategy

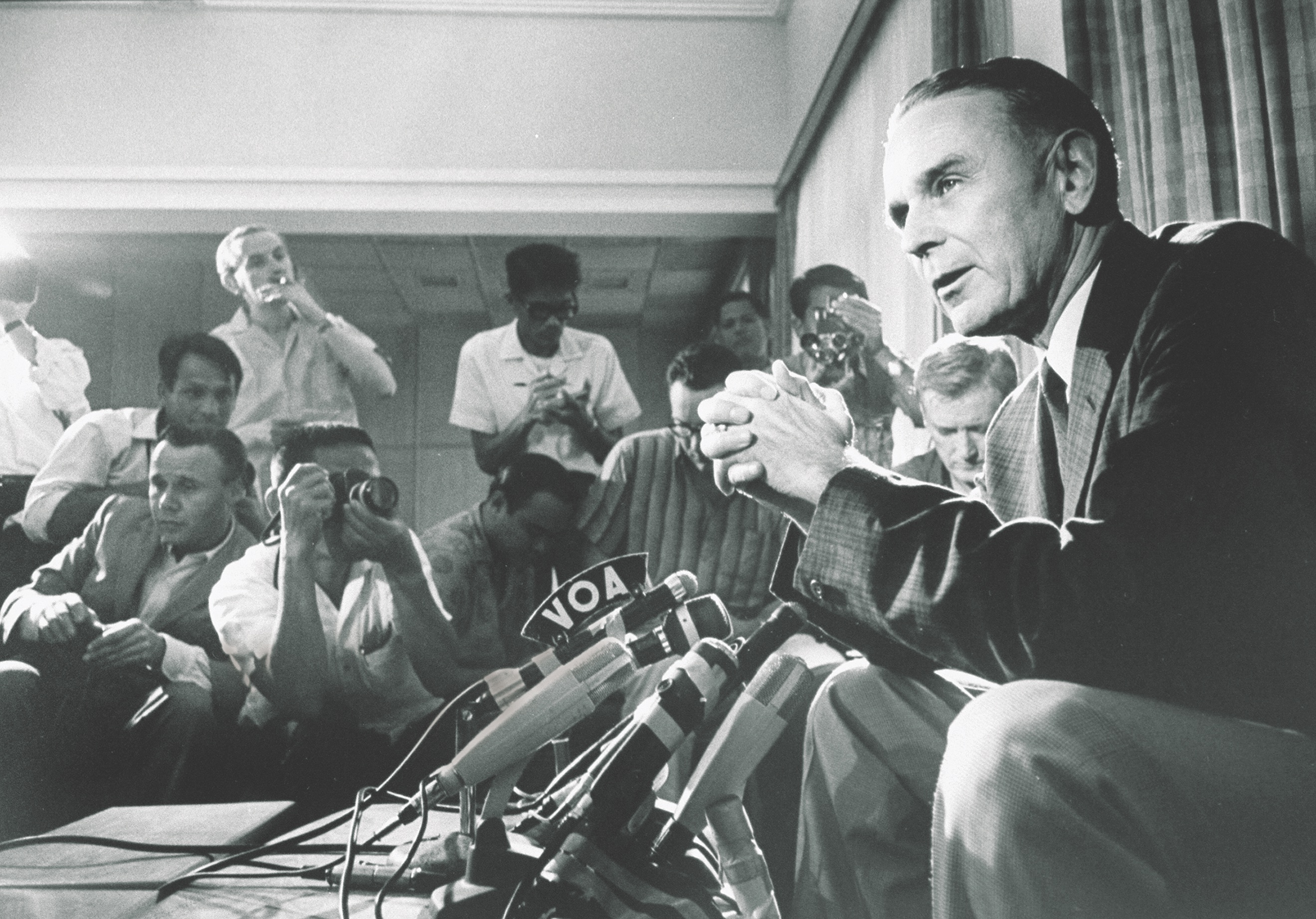

“I don’t like jumping out of airplanes,” famed World War II 101st Airborne Division commander Gen. Maxwell Taylor told the West Point Class of 1969. “I just like hanging out with guys that do.” With that, Taylor had every cadet in the audience firmly in the palm of his hand.

The West Point speech encapsulates Maxwell Davenport Taylor’s careerlong appeal—he was extremely intelligent, always sharp, and had an instinctive grasp of what his audience expected him to say. Regardless of the subject under discussion, Max Taylor seemed the most knowledgeable person in the room. At least, that’s the image he projected throughout his military and political service from 1922 to 1970, the last two decades spanning the Cold War’s most critical years.

Arguably, Taylor was, more than any U.S. politico-military leader, the “Architect of the Vietnam War,” as Ingo Trauschweizer claims in his superbly researched biography, Maxwell Taylor’s Cold War.

Trauschweizer surgically dissects “Taylor the Cold Warrior” to show why Taylor, after retiring in 1959, was brought back to public service and continued to influence America’s Cold War strategy. President John F. Kennedy was impressed by Taylor’s 1960 book, Uncertain Trumpet, advocating a “flexible response” to the Soviet threat, rather than Dwight D. Eisenhower’s “massive retaliation” nuclear Armageddon strategy. Kennedy made Taylor his White House confidant/“military representative” in 1961 and later appointed him chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (1962-64). Taylor was President Lyndon B. Johnson’s ambassador to South Vietnam during the war’s critical formative period (1964-65).

Trauschweizer summarizes Taylor’s complex character: “Taylor was one of the most influential American soldiers, strategists, and diplomats in the twentieth century. He was also a controversial figure, both in his own time and in ours. Most of Taylor’s contemporaries in the military admired his intellect and courage, but many felt he did not put it to good use.”

Trauschweizer writes that Joint Chiefs members found Taylor “dishonest and untrustworthy,” but Defense Secretary Robert McNamara thought “Max was the wisest uniformed geopolitician and security adviser I ever met.” Others characterized him as the hawkish “architect of American escalation in Vietnam” who pushed for the air war against North Vietnam, yet conversely “argued against the massive deployment of [U.S.] ground forces to South Vietnam.”

The book examines Taylor’s entire Cold War career, including the years when he was West Point superintendent, 1945-1949; U.S. commander in Berlin, 1949-51; 8th Army/United Nations commander in Korea, 1953-55; and Army chief of staff, 1955-59. But the second half, which describes Taylor’s role in the escalation of American involvement in Vietnam, is particularly revealing. Indeed, this book is one of the best accounts of the incremental progression (“controlled escalation” was Taylor’s euphemism) from providing South Vietnam with arms and advisers to committing hundreds of thousands of troops to a major war against North Vietnam.

Trauschweizer explains how China’s intervention in the Korean War (1950-53) influenced Washington policymakers, particularly Taylor, who oversaw the 1953 armistice ending the war. Washington’s fear of Chinese (and less likely, Soviet) intervention in Vietnam hung over the decision-making. Taylor later admitted he mistakenly believed air attacks on North Vietnam would prove decisive because the Korean experience had produced “a false sense that American airpower could again force Asian communists into a compromise peace.” Taylor “thought history could repeat itself,” Trauschweizer says.

In line with that thinking, as early as 1964 the U.S. “objective was a negotiated settlement [with Hanoi], not military victory.” Washington, in effect, consigned U.S. forces into a bloody limited war aimed merely at achieving a Korean War-style stalemate.

Taylor, as Johnson’s “point man” in Saigon, was the most convenient scapegoat for a failed strategy. National security adviser McGeorge Bundy told Johnson in March 1965: “Max has been gallant, determined and honorable to a fault, but he has also been rigid, remote and sometimes abrupt.” Bundy thought Taylor “a politically spent force who did not have the diplomatic tact to shape events in Saigon.” Taylor left South Vietnam and “official” government service in July 1965.

This article appeared in Vietnam magazine’s February 2020 issue.