Scientist Matthew Maury modernized navigation techniques but his racist politics have made him a pariah

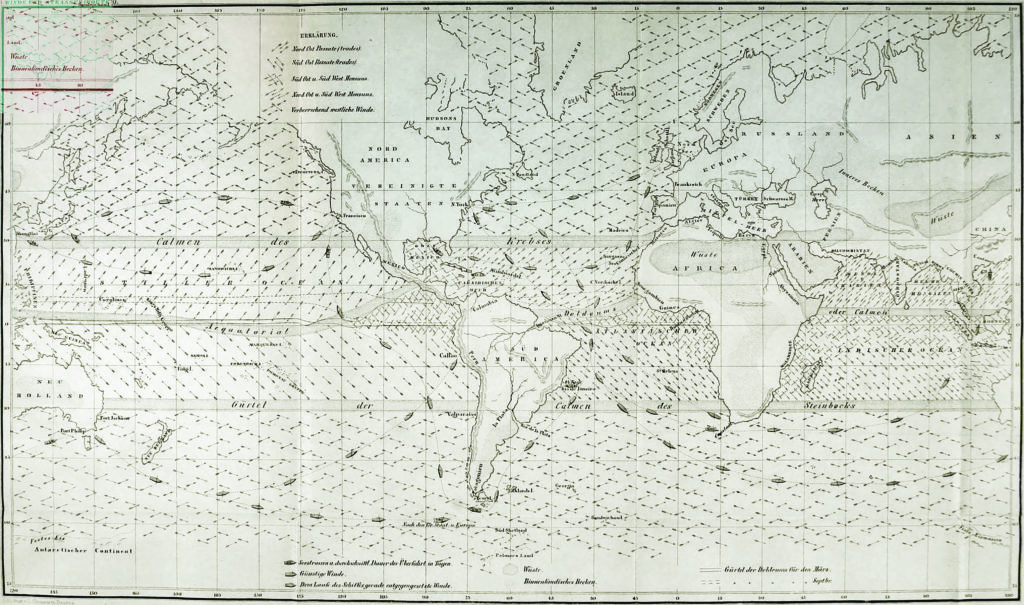

In October 1862 world-renowned scientist and former U.S. Navy officer Matthew Maury, sextant in hand, lay on the deck of a blockade runner departing Charleston, South Carolina, for England. After resigning his commission to join the Confederacy, Maury had sparred with its leaders over defending the Confederate coastline. Finding him a thorn in their sides, they had dispatched him to England, ostensibly to shop for ships. The blockade runner’s captain had lost his way, and Maury offered to chart a course by the stars. Maury, 55, had not been to sea for more than two decades but in no time, he was announcing a new course that would have the vessel to Bermuda by 2 a.m. That hour came and went, but within 10 minutes, there was the Bermuda shore, confirming Maury’s expertise at maritime navigation. Over his career, he systematized the old, amorphous method of crowd-sourcing logbook entries on winds, rain, currents, even whale migrations to deliver routes that cut some voyages by 30 days. That success opened the door for another effort Maury championed: the National Weather Service. Along the way, he devised underwater mines and torpedoes and helped gauge the feasibility of laying transatlantic telegraph cable on the seafloor.

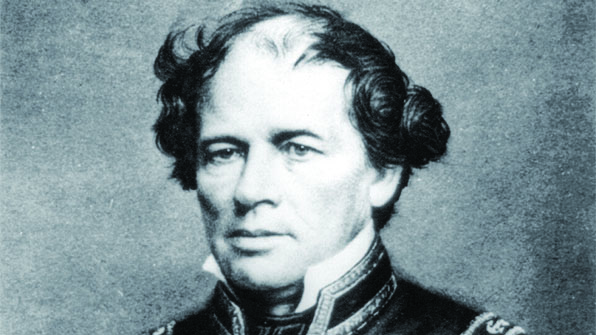

No figure in the Confederacy was more colorful, accomplished, and committed to White supremacy than Matthew Fontaine Maury. Born into a family descended from Huguenots arriving in Virginia in the early 1700s, Maury spent much of his youth in Franklin, Tennessee, where his slave-holding parents ran a not-very-successful farm. Seventh of nine children, Maury set his sights on the Navy, as his eldest brother had. Over his father’s objections, in 1825 he became a midshipman. He spent nine years at sea, visiting locales ranging from Brazil to the Marquesas Islands and teaching himself navigation, Spanish, and spherical geometry. In 1839, that career came to a grinding halt. A carriage accident in Virginia crushed his right leg, disqualifying him for shipboard duty.

Over the next few years, Maury remained a lieutenant at half pay. He established himself as a writer, penning sometimes anonymous and often scathing newspaper pieces about corruption in the Navy. His criticisms caught enough official attention that when his identity became known, he was appointed in 1842 to head the navy’s Depot of Charts and Instruments, a Washington, DC-based entity that doubled as the U.S. Naval Observatory. Rivals felt Lt. Maury did not deserve the position, lacking as he did training in astronomy, but he made up for that shortfall with other skills, creating a persona as a man of science for public benefit. Maury dove in, spending nights working at the observatory, located on a marshy stretch of Georgetown so riddled with mosquitoes that he and his coworkers regularly endured bouts of what would now be recognized as malaria. He also pushed to establish the U.S. Naval Academy.

In 1853, at Maury’s prodding, ten naval powers assembled in Belgium for a conference that ended with an agreement that all parties would collect oceangoing data and share their results with the U.S. Naval Observatory in exchange for receiving U.S. ocean charts. The United States would issue blank logbooks for recording the data, along with bottles that were empty but for blank logs corked inside to be tossed overboard and meant to be retrieved by passing vessels and recorded as floating markers. According to John Grady’s in-depth biography of Maury, conference host Leopold I of Belgium hailed the use of a ship as a “floating observatory, a temple of science.” By the late 1850s, more than 137,000 vessels were gathering wind, rain, and current information. The data dramatically shortened some commercial routes, saving millions in shipping costs. To help captains avoid collisions at sea, Maury proposed dedicated transatlantic sea lanes for traveling east and west.

In 1856, Maury was among Navy officers summarily retired, perhaps thanks to rivals like Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution and Senator Stephen Mallory (D-Florida), who chaired a committee on naval affairs. Maury fought to retain his commission—and succeeded. He had devoted his life to the U.S. Navy, but as the national rupture over slavery widened, he wrote, “The real question at issue is a sectional one; and with the South, it is a question of empire. Increase, multiply, and replenish the earth…” As many Southerners did, Maury envisioned America’s slaveholding empire expanding not only into the American West but also into Cuba and Brazil.

When Virginia seceded in April 1861, Maury submitted his resignation and offered his services to the Confederacy. Among its leaders was his foe Mallory. Maury tinkered experimentally with electrically detonated torpedoes, and Confederate ships deploying his inventions sank some 55 Union ships blockading Confederate ports. In 1862, he sailed to England to trade on his celebrity and secure ships for the Confederacy if he was able. Maury procured a couple of vessels and continued devising explosives.

In November 1865, the last Confederate troops surrendered. Now a man without a country, Maury approached Emperor Ferdinand Maximilian in Mexico, peddling a campaign to recruit former Confederates and freed Blacks to establish a slaveholding settlement. His scheme foundered. In June 1867 the Mexican opposition executed Maximilian, by which time Maury had found his way to England. In 1870, with ire against ex-Confederates ebbing, he returned to the United States and went to work at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, home of the institution that became Washington and Lee University, presided over by Robert E. Lee until his death in 1870. Maury drew the job of surveying Virginia resources to rebuild the devastated state. But he did not live much longer, dying in 1873.

Until then, Maury promoted broad collection of weather data—an inventory of patterns and forecasts as useful to farmers as maritime data had been to shippers. Formal collection and distribution of weather reports by telegraph began around 1870. Like the National Weather Service, Maury’s books, including his 1855 The Physical Geography of the Sea, survived him. A memorable passage likened the earth’s surface to the bed of an invisible ocean of atmosphere. (Jules Verne reportedly consulted the book.) Maury wove his Christian beliefs into his observations, creating a religio-mystical tone that irritated some who questioned his scientific bona fides. Yet his insights remain trenchant—”it is the girdling encircling air that makes the whole world kin”—and vivid: “…without atmosphere,” he wrote, “the bald earth, as it revolved on its axis, would turn its tanned and weakened front to the full and unmitigated rays of the lord of the day.”

For promoters of the Lost Cause—the ideology that imagined a valiant, chivalric South pulverized by its industrial foe’s superior resources and troop numbers—Maury was an attractive hero, esteemed worldwide yet also an unrepentant White supremacist. His name peppers roads and schools, including Maury Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Wealthy preservationist Elvira Worth Moffitt led a long campaign to erect a Maury memorial on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. “Pathfinder,” dedicated in 1929 on Armistice Day—a nod toward reconciliation—portrayed Maury as a thoughtful navigator. Maury’s unrelenting fealty to expanding slaveholding into what he called the “American Mediterranean” has come to tarnish his scientific legacy. In the summer of 2020, when Mayor Levar Stoney ordered the removal of Confederate monuments and symbols from perches throughout the city, “Pathfinder” was among them.

This story was featured in the August 2021 issue of American History Magazine. To subscribe, click here.