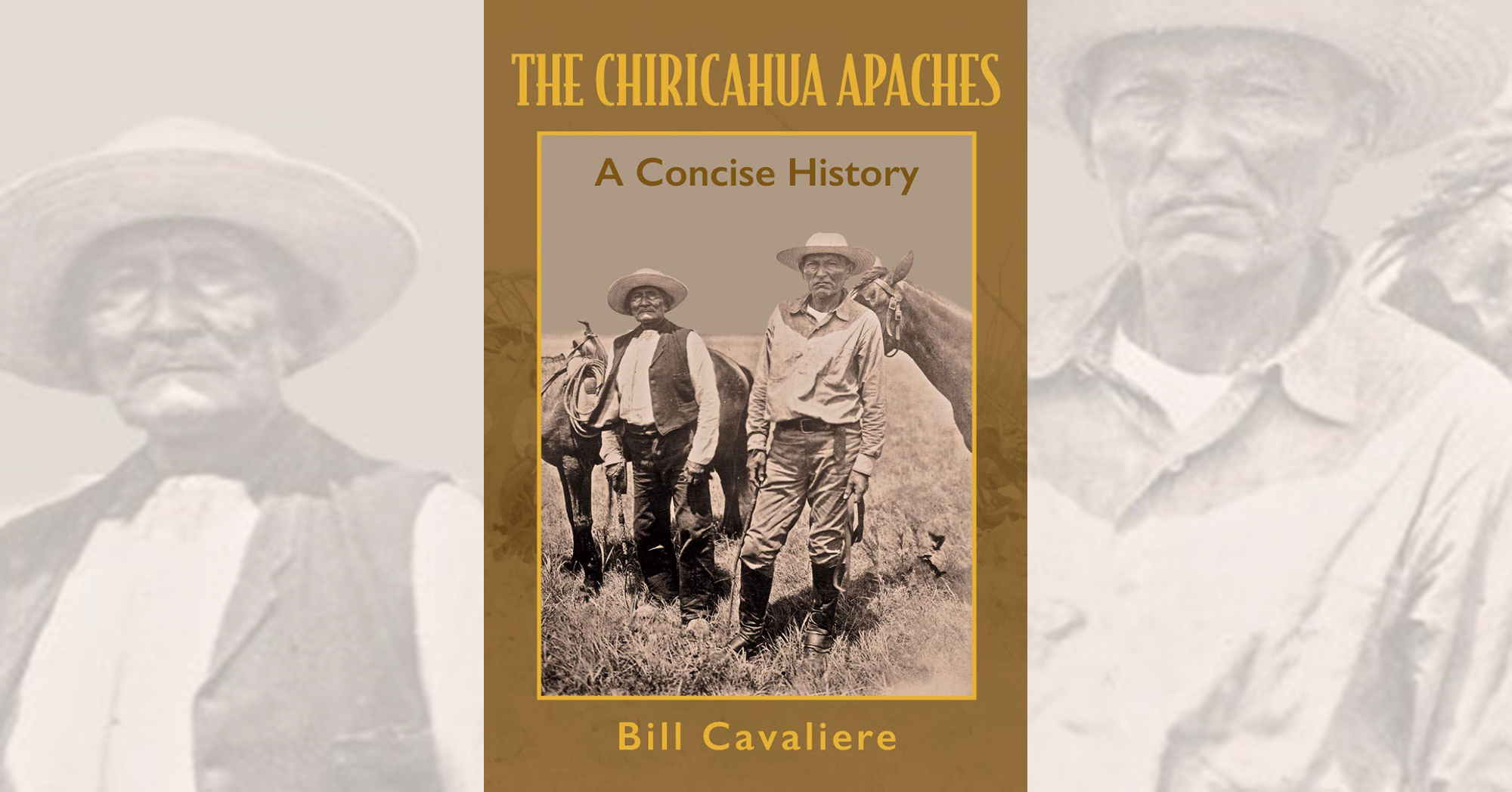

The Chiricahua Apaches: A Concise History, by Bill Cavaliere, ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution, Rodeo, N.M., 2020, $15.95

Concise can be nice. This well-illustrated 139-page book is to the point and points to one thing—that while 19th-century Chiricahuas often led hard, sad and violent lives, they wove a captivating history. Author Bill Cavaliere, president of the Cochise County Historical Society, dedicates his book to the late Edwin R. Sweeney, whom he calls “the world’s foremost authority on Cochise, preeminent Apache historian, dear friend and one of the most generous men I have ever known, who passed away while I was writing this book.” Sweeney, also a longtime friend of Wild West, wrote such well-researched, informative books as Cochise (1995) and From Cochise to Geronimo (2010). Cavaliere would be the first to dub those the definitive works on the subject. What his Concise History offers for those familiar with the in-depth works of Sweeney (as well as the Apache writings of Dan Thrapp and Robert Watt) is a solid summary of the high and low points of Chiricahua history. Others will appreciate Cavaliere’s compelling introduction to the action-packed world of Cochise, Geronimo, Naiche, Nana, Chihuahua, Loco and the rest.

“The story of the Chiricahua Apaches,” Cavaliere notes in his introduction, “is one of perseverance and tenacity, of courage and sorrow, and of triumph and tragedy. A fiction writer could not have come up with a more unbelievable story.” His first chapter relates the origins of the people who came to be called Apaches and formed seven distinct groups—Lipan, Jicarilla, Kiowa-Apache, Mescalero, Navajo, Western and Chiricahua. The Chiricahua comprise four bands—the Chokonen (Red Cliff People), Chihenne (Red Paint People), Nednhi (Enemy People) and Bedonkohe (Earth They Own It People). “Like the Nednhis,” writes Cavaliere, “there are no living full-blood Bedonkohes.”

By far the best-known Bedonkohe was Geronimo, a complex fellow who, while never a chief, arguably remains history’s most recognizable American Indian. That in part explains why he receives the lion’s share of attention in Cavaliere’s book. Other reasons include Geronimo’s many escapes from reservation life, his elusiveness when pursued by Generals George Crook and Nelson Miles, his various surrenders and his unexpected longevity (he died at age 79 in 1909). While some readers might be overfamiliar with Geronimo’s life, Cavaliere offers insight into the less spectacular Naiche, son of the great Cochise and the last hereditary chief of the Chiricahuas. Geronimo surrendered to General Miles at Skeleton Canyon, New Mexico Territory, on Sept. 3, 1886, but not until Naiche surrendered the next day were the Apache wars truly over. “Naiche was ultimately a tragic figure in several ways,” writes the author. “In addition to being constantly referenced as a weak leader, he also bore the humility of having to be the chief who surrendered his people. However, like his father, he was known for being levelheaded and honest.” In later life Naiche skillfully painted Apache scenes on deer hides and converted to Christianity, taking the name Christian Naiche.

—Editor

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.