The battle for the Southwestern desert was as crucial as the fighting back east

In the spring of 1861, all eyes were on South Carolina and Virginia. After the bombardment of Fort Sumter, large volunteer armies gathered at camps in the East, pledging to fight for the Union or the Confederacy. Professional soldiers and officers in the U.S. Army streamed in from posts west of the Mississippi. Many had resigned their commissions to fight for the South; others had been ordered east by President Lincoln’s War Department. That early in the war, it seemed unlikely that any of the fighting would take place farther west than Texas—in the territories of the desert Southwest.

In June 1861, a meeting in Richmond changed that.

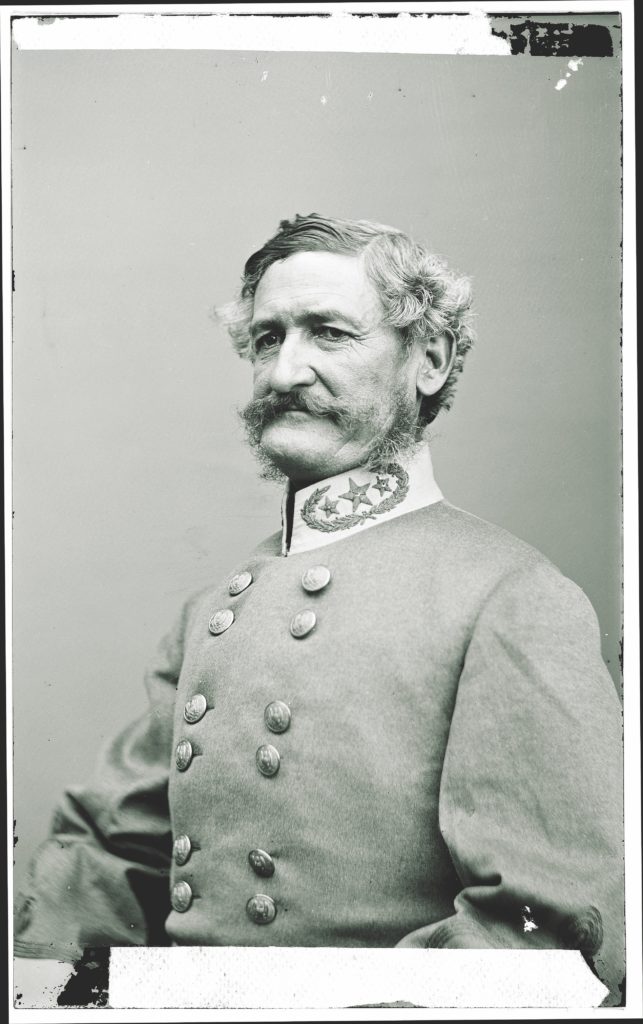

At that meeting, former U.S. Army officer Henry Hopkins Sibley convinced Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he could recruit an army of Texans and lead them west to take New Mexico Territory and then Southern California. From there, the Far West’s states and territories were all within easy reach, and the Confederacy would have access to the gold fields of the Sierras and Pacific ports to ship their cotton around the world. This would help fund the war in the East and create a continental Confederacy well-positioned to expand its empire of slavery once the Union had been defeated.

The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West tells the story of the 1861-62 Sibley Campaign as well as several other campaigns in the Southwest—a theater so often overlooked in histories of the Civil War.

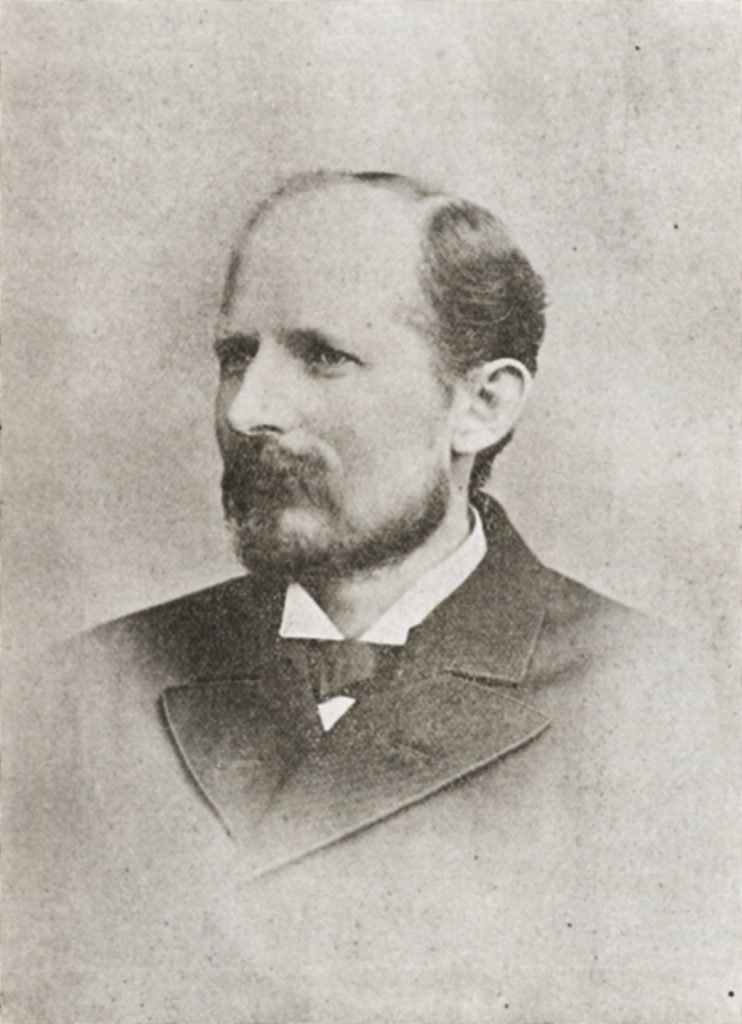

One of the Texans who volunteered to make Sibley’s vision a reality was 23-year-old lawyer William Lott Davidson. His story, told here, helps us understand the motivations of Texas soldiers who stayed out West and fought. Davidson, who saw action at the Battle of Valverde and then was wounded at Glorieta Pass a month later, crossed paths with others whose stories also shape the history of this region. That included Union Private Alonzo Ferdinand Ickis, who mustered into the army at a gold mining camp in the Colorado mountains and fought against Davidson at Valverde, and the famed frontiersman Kit Carson, who led the 1st New Mexico Volunteers—the Civil War’s first interracial army.

Davidson, Ickis, and Carson are three of the nine people whose stories are interwoven in The Three-Cornered War. Their collective experiences give readers a fuller sense of the Civil War Southwest’s complex history.

The struggles for power in the Southwest were an important aspect of the overall conflict and no mere sideshow. Expansion into the West had been driving the North and South apart long before the war, and control over the Anglo settlement of states and territories west of the Mississippi remained a central concern from 1861 to 1865.

The fights in the Southwest had a domino effect on the war in the East. After their victory at Valverde, the Texans took Albuquerque and Santa Fe, but were pushed back from Glorieta Pass when Union troops destroyed their wagon train. Without provisions, the campaign could not continue. When Davidson and his comrades staggered back to Texas in the summer of 1862, the gateway to the West’s ports and gold closed. From then on, the Confederacy had to finance the war by increasing burdens on its citizens.

Davidson penned a series of letters about the Sibley Campaign, which he and many other Texan veterans considered an important moment in American history. This wasn’t a war about only North and South—it was a truly national conflict.

As Union forces gathered around Santa Fe in October 1861, Bill Davidson reclined on his blanket on the banks of Salado Creek in western Texas. In July, Davidson had galloped into nearby San Antonio filled with Southern pride and optimism. The Mississippi native had moved with his family to Texas in 1853, when he was 15. Davidson was not a slaveholder, but he believed in the Confederate cause, and he expected that Sibley’s campaign to take the West would be successful. They would march from San Antonio to Fort Bliss in El Paso, join with Colonel John Baylor’s 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles in Mesilla, and then fight their way up the Rio Grande. After conquering New Mexico, they would take Colorado and Utah, and then move west to California. It seemed to him that the Confederates could “whip the whole United States in time to be home for Christmas dinner.”

The Sibley Brigade had been idling along the Salado, at a camp they had for three months called “Manassas” in honor of the Confederacy’s first great victory. Davidson had mustered into Company A of the 5th Texas, which was under the command of a man he knew well from home, Major John Shropshire. Every day, Davidson gathered with his “mess” mates on the camp’s parade ground to learn the arts of war: how to march in unison, form battle lines, and maneuver in combat.

When not drilling, the men occupied themselves with the usual camp activities, and they visited San Antonio. An especially delightful site was the Alamo, the storied building that had sheltered Texas rebels against Antonio López de Santa Anna’s Mexican army in February-March 1836. Although the Alamo was a site of slaughter and defeat, the men of the Sibley Brigade saw it as a shrine of Texas liberty, a symbol of the ultimate sacrifice made in the name of independence. The Texans’ compatriots in Virginia had Mount Vernon to gaze upon as inspiration for their war service. Sibley’s men were animated by the spirit of ’36 as they walked through San Antonio.

Soon, they would have a chance for their own fight for freedom. But when? As the days passed, Davidson became increasingly frustrated. While the men wiled away their time in camp, Union forces were undoubtedly amassing large numbers of troops along the Rio Grande. Why hadn’t they left yet for New Mexico? What was Sibley’s plan for them?

Sibley arrived in San Antonio just two weeks after Davidson. A career U.S. Army officer, he had coveted command all his life, but his quick temper and aversion to paperwork undermined his ambitions. Convincing Jefferson Davis to let him lead the campaign for New Mexico had been easy, perhaps because Sibley insisted he needed little financial help from the Confederate War Department: He would arm and provision the troops himself. But organizing his brigade and getting it going proved more challenging than Sibley expected.

Davidson believed in Sibley, and felt the brigade was among the finest armies in the nation. The Texas boys were “inbred from their earliest boyhood to hardships, used to camping out,” and, he felt, certainly braver than any Yank in the field of battle. The delays were maddening, however. It was outrageous to be “kept in idleness…all the while the Confederacy was needing our services.” He was not the only impatient one. On October 24, John Baylor wrote to Sibley that 2,500 Union soldiers were en route to Mesilla.

“Hurry up,” Baylor urged, “if you want a fight.”

On a dreary morning at the end of October, their boots sinking into the trampled mud of Camp Manassas’ parade ground, Davidson and roughly 3,000 others congregated to learn the time had come. “Such a cheer as rent the air was never heard before along the Salado,” Davidson wrote.

The 4th Texas would depart first; Davidson and the 5th two weeks after that, and finally the 7th, in mid-November. The reason for this seemed mysterious but was prudent. Once the Texans marched west of the Pecos River in western Texas, water would become harder to find. A drought had reduced most creeks in the region to lines of damp sand. There were wells and water holes, but they were unpredictable. Some might be brimming, fed by the fall’s massive thunderstorms. Others would just be pits of dirt. So, the Texans would be staggered along the road. This would allow waterholes time to refill. It was a smart strategy, and one that revealed how well Sibley knew the vagaries of the desert.

The 5th stopped first in San Antonio, where women lined the streets, waving handkerchiefs and cheering. The men received battle flags from well-wishers and stood at attention as the regiment’s commander, Colonel Tom Green, spoke to each company individually. “The Confederacy is counting on you,” he said, “and I, personally, am depending on you.”

A few miles from San Antonio, Green’s men were surprised to find Sibley sitting on his horse on a nearby hill. The general did not speak as they passed, but he lifted his hat in salute and watched as they marched out of sight over the flat blackland prairies. For the next week, Davidson and the others marched steadily westward, crossing rivers and creeks and trading with locals in small towns for butter, cheese, and milk.

One week in, however, storms gathered over the horizon and came at the 5th Texas with incomprehensible speed. They were blue northers—fast-moving cold fronts marked by rapid drops in temperature. Sleet pricked the soldiers’ skin and drenched their clothes as they shivered, no trees to protect them from the sweeping winds. Any man who had looked upon this march as a lark was disabused of his notion that night.

“We were tasting the bitter delights and mournful realities of the soldier’s life,” Davidson lamented. “We are now for the first time beginning to find out that we are engaged in no child’s play.”

After reaching Painted Cave—a rock shelter that was in Texas’ early days “a real resort for Indians, who have left upon the walls in the different compartments of the cave many of their crude paintings”—the 5th made a long, waterless haul to Howard Spring. When they arrived, they found a 12-foot-deep hole with the promise of water only at the very bottom. They pulled it up in buckets. It was a slow and wearying task.

Davidson struggled to find beauty in this parched landscape. The desert was a place of hardship and danger. They were halfway through the march and already their food supplies were dwindling. Most men had only beef and wormy crackers for meals; dying of thirst was a possibility. Worse perhaps, in the lands west of the Pecos, Mescalero and Lipan Apaches descended on every detachment that rolled past. When they raided Company A’s horses at Leon Holes, “the boys gave them a charge,” Davidson reported, “but the only result was that the boys ran their horses down.”

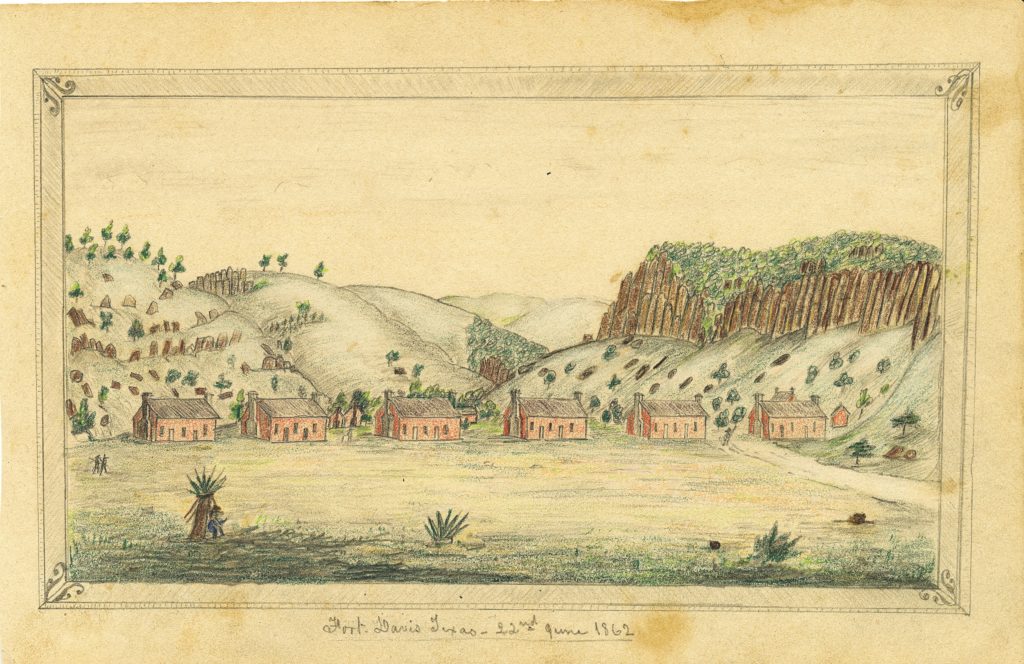

y that point, in early December 1861, the 5th had been on the road for one month and was still 100 miles from Fort Davis and 300 miles from Fort Bliss. There was some relief ahead, though. Limpia Creek Canyon rose out of the undulating plain and brought the men into the Davis Mountains. Vertical tubes of dark red volcanic rock towered overhead as the soldiers made their way up Wild Rose Pass. As they descended the western side toward Fort Davis, the scrub brush, yucca, and grasses gave way to a canyon floor lined with live oak trees.

The soldiers found the change in landscape refreshing. Even better was the sight of several supply wagons, sent by Baylor’s troops at Fort Davis. After eating their fill of sop and biscuit, Davidson and the others traded with a sutler, mailed letters home, and bought new clothes. Some bought liquor and “got tight,” which they regretted the next day when ordered to march 40 miles to Barrell Springs.

Davidson had predicted the Yankees would be whipped by Christmas dinner, but when the 5th finally reached Fort Bliss on December 24, he and the brigade were still in Texas and Davidson hadn’t yet seen an enemy soldier in person. He was relieved, though, to have a roof over his head and corn for his horse.

At Fort Bliss, Davidson learned Sibley was absorbing Baylor’s command into the brigade. That excited Davidson, who wrote: “These are a glorious set of boys. The bravest of all brave soldiers and truest of all true friends.”

After restructuring his army, Sibley issued a proclamation throughout Arizona and southern New Mexico, in both English and Spanish, announcing his intentions. “An army under my command enters New Mexico,” he declared, “to take possession of it in the name and for the benefit of the Confederate States.”

Sibley reassured residents that he did not intend to wage war but to “liberate them from the yoke of military despotism erected by usurpers upon the ruins of the former free institutions of the United States.” He felt sure that Hispano New Mexicans would volunteer to fight for the Sibley Brigade and donate wheat, corn, and animals to the Confederate cause. Surely they were as much the enemies of the federal government in Washington, D.C., as were the Texans.

Davidson, however, was less concerned about recruiting New Mexicans than recovering from the long march. He found Fort Bliss a pleasing place, and even in winter the river valley was lush with green grass. The boys would make forays across the Rio Grande to explore the Mexican town of El Paso, where they feasted on the tamales, fresh fruit, and vegetables they bought in town markets.

In early January 1862, Sibley commended the Texans for their comportment on the 600-mile march from San Antonio to Fort Bliss, expressing “his high appreciation of the patience, fortitude, and good conduct, with which, in spite of great deficiencies in their supplies, they have made a successful and rapid march…through a country entirely devoid of resources.”

It was the longest single march a Confederate army had yet undertaken during the war, and the conditions were unlike any their Eastern Theater comrades had faced. But it had taken a toll on the Texans. Would they recover enough by the time Sibley called them into battle? Would they be able to sustain themselves on the way to Santa Fe? Davidson could only guess at the answers.

On February 15, 1862, Davidson and the 5th Texas marched through a howling snowstorm and halted just shy of Fort Craig in the New Mexico Territory, the winds blowing “so hard as to almost pull the face off a man.” Gathering around their campfires, they cracked jokes and sang “as merrily as if they were at home,” trying to make the best of things. They were in bad shape, however.

They had been encamped around Fort Thorn, a former U.S. Army installation 40 miles north of Mesilla, for more than a month. The rest after the long march from San Antonio was good, but the camp had become a hotbed of disease, with outbreaks of measles and smallpox, and many men suffering from exposure-related illnesses such as pneumonia.

“The thought naturally presented itself,” Davidson mused, “how many of these noble men, now so full of life and hope, will ever live to see Texas soil again.” Everyone knew that “toil and suffering and danger is ahead of us. We know that hard blows are going to be given and received. We know that some will be killed, but how many and who, time will tell.”

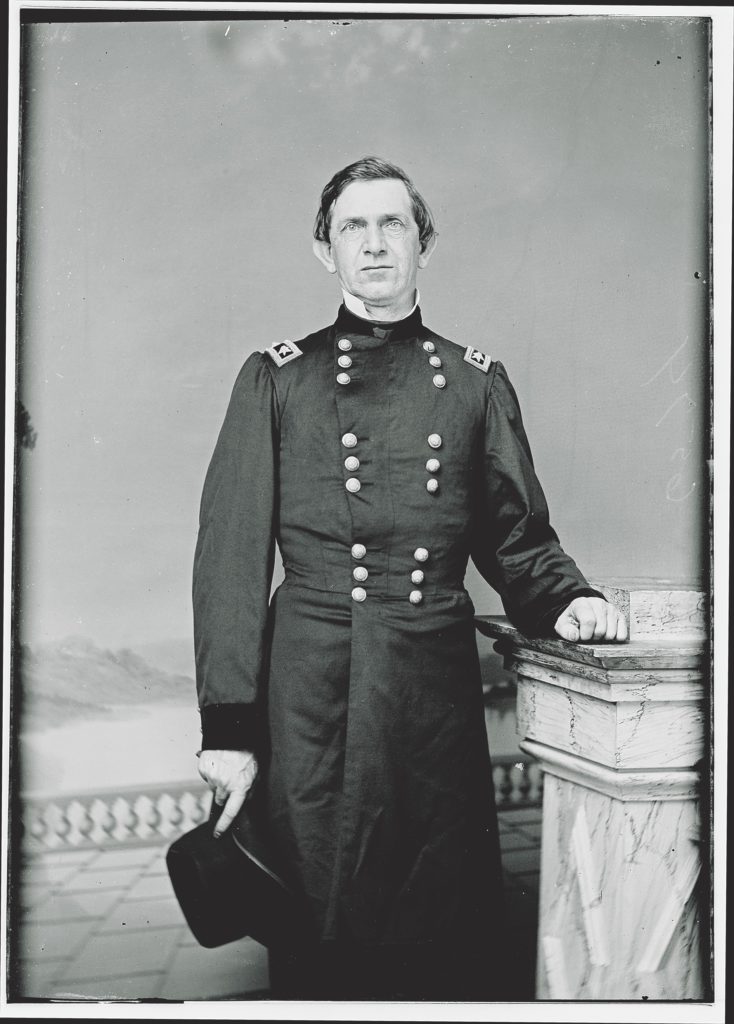

Although the thought of battle made them anxious, the Texans were also happy to be on the move toward a fight. Early in the morning of February 16, they began the 85-mile march to Fort Craig. As they formed a line of battle, the Army of the Department of New Mexico, under Colonel Edward R.S. Canby (“Richard,” as his wife, Louisa, preferred), came out to meet them. Private Alonzo Ickis and his fellow soldiers in blue assembled on the plain south of the fort, and the Texans watched them come. A Confederate private broke the silence.

“Gee whilikens captain, I ain’t half as mad at them fellows as I was before they showed up so many men,” he cried out. “Let’s go home to mother!”

The Texans roared with laughter.

Davidson had to admit it was an impressive picture. The Yankees “did not seemed scared a bit. They ran up their flag on the mast within the fort and cheered like they were trying to split their throats.”

Not to be outdone, Davidson and his comrades “waved our flag and gave them a round yell” back.

The Texans didn’t consider being outnumbered a problem, believing their 2,500 men were more than a match for Canby’s 3,800. Both armies were small, however, compared to those in the Eastern Theater, where more than 100,000 men had been fighting against one another on battlefields in Virginia and Tennessee. Nevertheless, Canby’s army and Sibley’s Brigade were the largest fighting forces ever seen in one place in the desert Southwest. New Mexico had a long history of violent conflict, but those battles usually involved small groups of armed raiders and soldiers using guerrilla tactics. The scarcity of food and water in the high desert meant that sustaining large armies for long periods was a challenge. Both Canby and Sibley wanted to defeat the other as quickly as possible because of it.

For two hours, the Union and Confederate armies maneuvered in front of each other.

“It looked to me,” said Davidson, “like two boys in my school days, daring each other to knock the chip off the other’s shoulder and each afraid to do so.”

Canby had the high ground and knew it would be folly to give it up. He might have thousands of men, but many of them were green militiamen and volunteers. He had little confidence in either Kit Carson’s New Mexico Volunteers or in “Dodd’s Independents”—Captain Theodore Dodd’s company of Colorado infantrymen, which included Ickis. So, Canby stayed put and dared the Texans to come at him.

Sibley recognized that any charge on the Federals would be hopeless. While he, like Canby, did not believe that the Union volunteers would fight, Sibley knew that the Army Regulars would. A few of them had been under his command at Fort Burgwin, near Taos, before he had resigned his commission in the U.S. Army. They were professional soldiers, all of them “reared in camps of instruction and trained to deeds of war and not peace.” The Texans were skilled with their rifles and full of enthusiasm, but Sibley knew that familiarity with the ways of war usually won the day on a battlefield like this.

As night fell, therefore, both armies withdrew. “We thought the ball was about to open,” Davidson grumbled.

Sibley was disappointed Canby hadn’t taken the bait. The general had known Canby and his wife well from antebellum campaigns in Utah and New Mexico. He anticipated Canby would defend his fort and fight according to established military practice, even in a desert landscape not suited to large-scale, long-term battles.

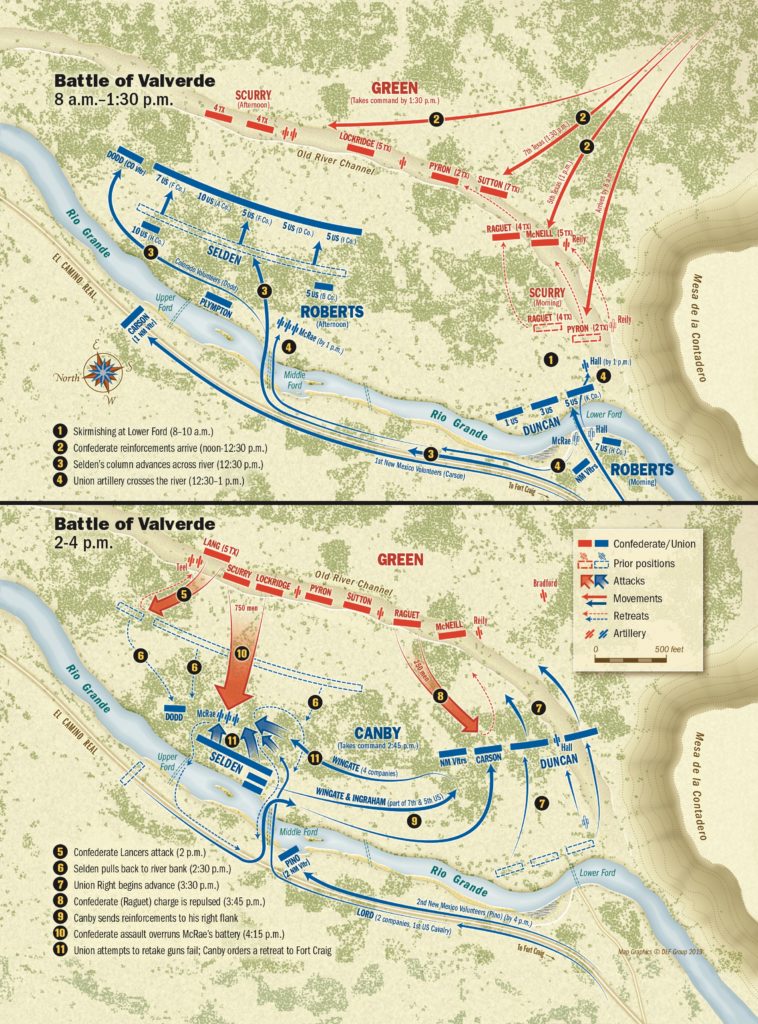

The Texans needed another plan that would confound Canby with its boldness. Sibley decided to cross the Rio Grande east of their camp, putting the river between them and the Union artillery at Fort Craig. Then they would follow ridges of drifting sand, parallel to the river. This route would conceal their movements and secure them “from attack by the impracticable nature of the country.” When they passed Mesa de la Contadera, they would re-cross the Rio Grande to get between the Yankees and their supply base at Santa Fe. This would force Canby out of Fort Craig and bring on a battle on a field of Sibley’s choosing.

But where to ford the river north of the Mesa? Sibley, who had traveled El Camino Real several times, chose a broad plain marked by the ruins of a pueblo and a hacienda. Here, the Rio Grande changed its course several times as it ran up against the Mesa, creating a broad basin of low sand hills where the riverbanks used to be. Some Hispanos called it Contadero; most Anglos knew it as Valverde.

On February 20, Canby sent several hundred troops across the frigid river in an effort to cut off the Texans from their water supply. In the mix were Carson’s 1st New Mexico Volunteers, Dodd’s men, and a company of militia mustered in only a few days before. The Confederates lobbed shells in their direction, but, as Ickis noted with frustration, “We [could not] return fire as we [were] far below them.” As the shots rained down, the militiamen broke and ran. Canby ordered Carson and Dodd to follow them back across the river. But some soldiers were left to defend the river.

Davidson and his comrades cheered as they watched. It was the full-throated Rebel Yell, which the Texans always claimed had originated during the Rangers’ wars with Comanches in the 1840s and ’50s. As it echoed over the valley, Davidson felt sure it “must have sent a chill to the hearts of the boys in blue.”

Now late in the day, Sibley ordered the men to camp in place. The next morning they would march toward Valverde and bring the fight to the Yankees. The men burned mesquite and sat around the fire, casting bullets from melted lead bars. Later that evening, Colonel Green told Company A: “Boys, you’ve come too far from home hunting a fight to lose. You must win tomorrow, or die on the battlefield.”

At Fort Craig, Canby tried to anticipate Sibley’s next move. The Texans might continue marching northward and attempt to cross the Rio Grande at the Valverde ford. They might maneuver southward again and re-cross the river to charge the fort from that direction. Or they might attempt an assault from their current position on the lava ridge across the way.

Protecting Fort Craig was paramount. Well supplied, the Federals could withstand a siege, if it came to that. Still, Canby knew he couldn’t let Sibley trap him and cut off him off from Santa Fe. Also, his soldiers were eager to fight. He couldn’t keep them back much longer.

Early on February 21, Canby made his decision. He’d stay at Fort Craig while his second-in-command, Benjamin Roberts, took a mixed regiment of Regulars, New Mexico Volunteers, and artillerists to Valverde, to occupy and hold the ford. Carson would take the 1st New Mexico, the militia, and Dodd’s Independents back across the river before the fort. If it became clear Sibley was turning south or charging across the river, Carson’s forces would “impede his movements as much as possible.”

As Company A went about “our usual morning duties—some digging roots, others moving their horses, and others cooking breakfast,” 200 of their compatriots in Baylor’s former regiment—the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles—rode suddenly out of camp toward the ford, eager to get “a square drink of water.”

Davidson went back to his breakfast, trying to make the best of things. Some of the men held a piece of tin over their cookfire with sticks, and then picked lice out of their clothes and placed them on the metal. The men gathered to place bets “on which one got off that hot tin first.” In this way, they passed two pleasurable hours.

The sun was up over the mountains and just beginning to warm the chilly air when Davidson heard the pop-pop-pop of rifle fire. Faint but distinct, coming from somewhere past the Mesa. The camp snapped to attention. “Every fellow sprang to arms and for his horse,” but their officers told them to stand down. They would receive orders when Sibley wanted them to move.

The Federals in the sand saw a flurry of activity up at the Texan camp. Soldiers were leaping on their horses and riding hard for Mesa de la Contadera. Carson sent a courier back across the water with this intelligence, advising Canby that the enemy was headed toward Valverde. Upon his return, the courier relayed orders for Carson to leave a contingent of soldiers along the bank and proceed with the rest of the 1st New Mexico and Dodd’s Independents to the battlefield, delighting Ickis.

After a few hours, the 5th Texas was ordered forward, drawing a cheer as the men mounted their horses. By their side were two companies of cavalry under the command of Captain Willis Lang. It was a strange sight. Rather than swords, Lang’s troopers held aloft lances that Sibley had made for them back in San Antonio.

Passing Mesa de la Contadera, the horsemen moved down into a narrow canyon, which funneled them into the northern edge of the plains of Valverde. They poured out of the ravine to find themselves on the far right of the Confederate line, facing the Rio Grande and more than 1,000 Union troops. Davidson had barely registered their position before several comrades were shot off their horses.

At that moment, Ickis arrived on the west bank of the Rio Grande, across from the battlefield. He couldn’t see much, as a large number of cottonwood trees were clustered between Dodd’s Independents and the enemy—their flat, spreading branches obscuring most of the field. Gunfire smoke drifting through the trees didn’t help. The Union artillerists had been hotly engaged for two hours and had driven the Texans behind the sand embankments that formed a natural trench east of the river.

Soon, Dodd’s men began wading over, “selecting step by step their foothold among quick sands and against the strong current…up to their arms in its water.” Once through, Ickis pressed his back against the dark red bark of a cottonwood tree and fixed a bayonet onto his rifle before proceeding through the woods toward the Confederate line.

Behind the sand bank 400 yards away, the 4th Texas waited. Its colonel, William Scurry, divided his command to meet the threat, ordering those with Minié rifles to pick off Yankee officers while the rest of the men waited until the soldiers came within range of their shotguns. If a sharpshooter was wounded or killed, his rifle would be “given to one of the shotgun men, who was put in his place.”

As the battle continued to unfold, Dodd’s men clashed hand-to-hand with Lang’s Lancers, which brought them close to the Texan lines, within range of the Confederates’ double-barreled shotguns. The 4th and 5th Texas rose onto the lip of the sand hill and took aim at the Federals. Ickis and the others backed away slowly, picking up abandoned guns and dragging wounded men with them. When they arrived back at the Union line, Dodd’s company threw themselves on the sand behind a battery of six cannons commanded by seasoned artillerist Captain Alexander McRae. They ate some rations and replenished their ammunition pouches. McRae soon had his guns in action.

Snow flurries continued to swirl, flakes coming to rest and then melting on the torn bodies of men and horses. Behind the sand banks in the center of the Confederate line, Davidson clutched his shotgun and laid as flat as he could, shivering. At some point, he had lost his hat. A discarded lance lay nearby, so he crawled over, picked it up, untied the red and white flag from its tip, and secured the flag around his head. This kept him slightly warmer, but he knew the red kerchief would now be a target for the Yankee gunners.

“Under all military rules and science we were whipped,” Davidson conceded. “Outflanked on our right, outnumbered more than two to one in the center and an enfilading fire on our left…” It seemed the Confederates had little choice: Retreat or surrender.

Farther down the line, Green called the officers together. Sibley was sick, the colonel informed them, and had chosen to stay behind in the camp on the lava ridge. The officers looked at one another knowingly. It was an open secret that Sibley was a drunk, and that his frequent bouts of “illness” were due to his fondness for the whiskey keg. The general’s incapacitation meant Green was now in command of the field of battle. The Texans had no path of retreat, but the colonel wasn’t considering surrendering. They had come too far not to fight until the end.

Reports from Roberts indicated the battle had intensified, so Canby left a small group to defend Fort Craig and brought the rest of his men with him. When they came around the north side of Mesa de la Contadera, the commander could see the flashes of artillery fire and smoke billowing at the ford. He urged his horse through the river to join Roberts behind the Federal line. Concerned by Confederate artillery on the Union right, and that Mesa de la Contadera was unoccupied, Canby had the New Mexico Volunteers, a regiment of Regulars, and two heavy guns sent there.

What Canby seemed unaware of was that Carson’s departure had weakened his center. Though McRae’s battery was there, only about 300 men, including Dodd’s Independents, remained to defend it. Green realized there was now a gap in the Union center and sent a regiment to engage Carson, before informing his company commanders to prepare for a charge. McRae’s guns were the target: Take those cannons, he ordered, and break the Union line.

Upon hearing the order, Davidson buckled on his Colt six-shooter, stuffed ammunition in his pockets, grabbed his shotgun, and waited. When Shropshire finally cried, “Come on, my boys!” Davidson jumped up, leapt over the edge of the sand hill, and began running toward the Union guns 700 yards away. The ground was mostly level, dotted with cottonwoods, and Davidson quickly realized the grass was on fire. Small flames licked at his heels as he ran.

McRae turned his guns on the advancing Texans, and men around Davidson began “falling, bleeding, dying at every step.” As they readied themselves for the onslaught, Dodd’s men felt a sudden shift in the lines behind them. “At the first sight of such a very large body of Texans,” Ickis would complain bitterly, the militia ran toward the river, “leaving us white men only to hold the section or let it go.”

With each cannon blast, Ickis recalled, “[y]ou could see their ranks open and pieces of men flying in the air….[But] they still came down upon us.”

There was no time to pull the battery back across the river, and the gunners were able to spike only a few cannons before the Texans were upon them. McRae was hit twice by bullets but kept firing, finally killed where he stood by a third shot.

“It was not in human power to stop or resist that wave,” Ickis lamented.

One Union artillerist jumped on a magazine at the side of the guns and drew his pistol, crying “Victory or death!” before firing into the ordnance. The explosion was one “loud crash” and “all was over with that brave boy,” Ickis recalled. “The explosion must have killed several of the enemy, [who] were thick as they could stand.”

Company A had just recovered from the shock of this blast when they heard the familiar sound of rifle fire—from an unexpected direction. They turned and saw a company of soldiers heading their way. At first, the Texans thought these were their own men and ceased firing, only to learn it was Carson’s men.

Canby “for some moments entertained…hope that the battery, and with it the fortunes of the day, would yet be saved.” But then he decided that even Carson’s men couldn’t disperse the charging Texans and “that to prolong the contest would only add to the number of our casualties without changing the result.” He ordered a retreat.

When Davidson realized what was happening, he and his mates turned the cannons and tried to figure out how to work them. “Oh hell, we don’t know which end of the thing goes foremost,” he said and waved to the others, “Let’s cut them fellows off.”

Watching Union infantry and cavalry splashing through the water, and artillerists abandoning guns midstream, Davidson began shooting as fast as he could load. Confederate gunners arrived at McRae’s battery and began pouring a “perfect shower of shot” at the desperate Federals. Some of the struck soldiers fell face-down into the water, spinning off into the current.

When a Union rider galloped up to the bank, holding aloft a white flag, Davidson was sure it was a flag of surrender and cheered. It was actually a flag of truce. Canby wanted a cease-fire to gather the wounded and dead.

Green sent word to Sibley that the Texans had won the day. The road to Albuquerque and Santa Fe was now open to the Confederates. One problem, however. Capturing Fort Craig had been central to Sibley’s plan to conquer New Mexico Territory. Although they proved they could win a battle in the high desert, they had lost their best chance to take the fort. Officers were unsure what effect that would have on the men.

The next day, it was reported that the Texans were on the move, marching toward Albuquerque. They had Captain McRae’s cannons with them, mementoes of their victory that they henceforth referred to as “The Valverde Guns.” Canby’s army was trapped between Sibley’s men to the north and Baylor’s to the south, and its supply line was severed. The general rushed couriers toward Albuquerque and Santa Fe to warn the citizens: The Texans were coming.

_____

Futile Spectacle

Buying firearms on the open market, Henry Sibley by late fall had his brigade equipped with “squirrel-guns, bear guns, sportsman’s guns, shot-guns, both single and double barrels[;] in fact, guns of all sorts,” according to one report. Sibley also procured 200 lances, to be carried by Captain Willis L. Lang’s company in the 5th Texas Mounted Volunteers. Nine feet long with 3- by-12-inch blades, they were topped by large red pennants with a white star in the middle: the original Texas flag. Sibley had first seen lancers in battle during the Mexican War, and the aesthetic splendor of that vision had stayed with him. It would be difficult to train the men to fight with the lances, and with their motley collection of guns. There was no help for it, however. Sibley’s men would just have to do the best they could.

During the Valverde fighting, Union Private Alonzo Ickis was among those startled to see the sudden appearance of 50 Confederate horsemen, riding at a gallop and holding long spears with gleaming metal blades and red flags affixed to them, bearing down on them.

When Captain Theodore Dodd saw Lang’s Lancers coming, he worked quickly, remembering his West Point training on cavalry charges. He organized Ickis and the other men into a small hollow square: The men stood two deep, the first rank kneeling with their bayonets and the second rank behind them standing up, waiting with their guns, ready to shoot.

“Steady there my brave mountaineers!” Dodd yelled. “Waste not a single shot. Do not let your passions run off with your judgment.”

The Lancers sped toward them, closing the gap.

“Steady men, steady, do not fire until I command.”

There was no sound in the company ranks. Ickis could hear his own heartbeat.

“Steady, men,” Dodd ordered. “Guns to faces but wait for the command to fire.”

The horsemen came within 40 yards of the Coloradans, and it was then that Dodd gave the command.

“Fire!” he yelled. “They’re Texans! Give ’em hell!”

Ickis, in the second row, fired his gun. Then came the dull thud of the impact of bullets in flesh, the terrified bleats of horses, the screams of men. When the smoke dissipated, Ickis could see that “many brave Texans [had] bit the dust, many horses were riderless.” The rest of the Lancers wavered for a few moments and then “on they came and fierce fellows they were with their long lances raised.”

The Coloradans reloaded their guns, and “we gave them a second volley,” Ickis recalled. “They appeared bewildered, did not appear to know how or what to do.”

Ickis and his comrades took advantage of the Texans’ confusion and leapt upon them, stabbing and bludgeoning the Confederates with their bayonets. One of Dodd’s men ran his bayonet through one Texan “and then shot the top of his head off” for good measure.

The Lancers “were soon butchered,” Ickis wrote. “I cannot call it else.”

Captain Lang staggered back to the Confederate lines, mortally wounded. He did not know how many soldiers he had lost. Half of them at least, maybe more, and nearly all of the horses. The men of the 4th and 5th Texas looked on, temporarily stunned. It had been a gallant charge, but a doomed one. –M.K.N.

_____

A Steep Price

The night of February 21, 1862, both the Texans and the Union troops moved slowly through the plains of Valverde, following the sounds of groans to the bodies of men. They carried the wounded to their respective field hospitals and heaved the dead into wagons, “as many as could lay side by side.” Bill Davidson heard a faint call and followed it, finding a friend of his who had been shot through both thighs and had waited all night for help.

“How we missed finding him so long is a mystery to me,” Davidson noted sadly, “as I had passed several times within ten feet of him, hunting specially for him.”

After retreating across the Rio Grande, despondent Union Private Alonzo Ickis marched back to Fort Craig. In his tent, he tallied the company’s losses. He guessed that there were 40 men dead, wounded, or missing from Dodd’s Independents alone. Added to those who had fallen to illness before Valverde, the “Brave Mountaineers” had lost more than half of the men they had started with from Cañon City, Colorado. This was a very high casualty rate for one company, across all theaters of the war, and 20 percent of the total Union killed and wounded at Valverde.

After retreating across the Rio Grande, despondent Union Private Alonzo Ickis marched back to Fort Craig. In his tent, he tallied the company’s losses. He guessed that there were 40 men dead, wounded, or missing from Dodd’s Independents alone. Added to those who had fallen to illness before Valverde, the “Brave Mountaineers” had lost more than half of the men they had started with from Cañon City, Colorado. This was a very high casualty rate for one company, across all theaters of the war, and 20 percent of the total Union killed and wounded at Valverde.

“Many of the boys with whom I was acquainted in the mountains are dead and wounded,” Alonzo wrote dejectedly to his brother, Tom. “These were trying times if I have seen any.”

At dawn on February 22, the men of the Sibley Brigade gathered more than 30 bodies together, side-by-side. They had selected a burial ground near the site of their greatest achievement during the battle: the capture of McRae’s battery. At 10 a.m. the entire army gathered there, the chaplain said the funeral service, and Bill Davidson offered up a heartfelt prayer. Then they buried their comrades, wrapping them tightly in blankets and coats and laying them in three long trenches. They shoveled the dirt over the piles and left no other markers. They reckoned that the cottonwood trees that clustered all around would have to do. These “grand shapely old monarchs of the plains” would stand as sentinels, protecting the Confederate dead in the deserts of New Mexico.

While the Texans buried their men, Ickis walked toward one of Fort Craig’s storehouses, which had been converted into a dead room. He had seen the wagon teams as they brought the bodies back to Fort Craig the day before, heard the “shrieks of the wounded and dying together” as the ambulance men carried them to the field hospitals hastily erected outside the fort’s walls. And he had seen “the ghastly appearance of the dead” as they were taken to the storehouse. Ickis went there to look for several friends. He had lost track of them during the retreat and they were nowhere to be found.

He opened the door and walked in. The bodies were heaped upon one another. Ickis climbed around them, peering into their faces. One of the bodies he clambered over was Lieutenant George Bascom, the U.S. Army officer whose fight with Cochise at Apache Pass in 1861 had provoked the Chiricahuas into a campaign of revenge. He had been shot in the retreat and caught in an eddy in the Rio Grande. The state of the bodies in the dead room was a shock. Ickis had never seen so much blood or so many mangled limbs.

On February 23, Union soldiers buried 50 men in Fort Craig’s graveyard, “each in a separate coffin, an act seldom seen in a time of war.” The artillerymen fired three volleys over the dead, which echoed across the valley.

“Their bodies will there rest in peace,” Ickis was sure, “but their names and acts will live to form one of the brightest pages in the history of the war against Infamous Rebellion [and] deep double-dyed treason.”

–M.K.N.

Copyright © 2020 by Megan Kate Nelson. From The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West by Megan Kate Nelson to be published by Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc. Printed by permission. This story appeared in the March 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.